Algerian Civil War

The Algerian Civil War (Arabic: الحرب الأهلية الجزائرية), known in Algeria as the Black Decade (Arabic: العشرية السوداء, French: La décennie noire),[24][25][26] was a civil war fought between the Algerian government and various Islamist rebel groups from 26 December 1991 (following a coup negating an Islamist electoral victory) to 8 February 2002. The war began slowly, as it initially appeared the government had successfully crushed the Islamist movement, but armed groups emerged to declare jihad and by 1994, violence had reached such a level that it appeared the government might not be able to withstand it.[27] By 1996–97, it had become clear that the Islamist resistance had lost its popular support, although fighting continued for several years after.[27]

The war has been referred to as 'the dirty war' (la sale guerre),[28] and saw extreme violence and brutality used against civilians.[29][30] Islamists targeted journalists, over 70 of whom were killed, and foreigners, over 100 of whom were killed,[31] although it is thought by many that security forces as well as Islamists were involved, as the government had infiltrated the insurgents.[32] Children were widely used, particularly by the rebel groups.[33] Total fatalities have been estimated at 44,000[34] to between 100,000 and 200,000.[35]

The conflict began in December 1991, when the new and enormously popular Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) party appeared poised to defeat the ruling National Liberation Front (FLN) party in the national parliamentary elections. The elections were canceled after the first round and the military effectively took control of the government, forcing pro-reform president Chadli Bendjedid from office. After the FIS was banned and thousands of its members arrested, Islamist guerrillas rapidly emerged and began an armed campaign against the government and its supporters.

They formed themselves into various armed groups, principally the Islamic Armed Movement (MIA), based primarily in the mountains, and the more hard-line Armed Islamic Group (GIA), based primarily in the towns. The GIA motto was "no agreement, no truce, no dialogue" and it declared war on the FIS in 1994 after the latter had made progress in negotiations with the government. The MIA and various smaller insurgent bands regrouped, becoming the FIS-loyalist Islamic Salvation Army (AIS).

After talks collapsed, elections were held in 1995 and won by the army's candidate, General Liamine Zéroual. The GIA fought the government, as well as the AIS, and began a series of massacres targeting entire neighborhoods or villages which peaked in 1997. The massacre policy caused desertion and splits in the GIA, while the AIS, under attack from both sides, declared a unilateral ceasefire with the government in 1997. In the meantime, the 1997 parliamentary elections were won by a newly created pro-Army party supporting the president.

In 1999, following the election of Abdelaziz Bouteflika as president, violence declined as large numbers of insurgents "repented", taking advantage of a new amnesty law. The remnants of the GIA proper were hunted down over the next two years, and had practically disappeared by 2002, with the exception of a splinter group called the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC),[Note 1] which announced its support for Al-Qaeda in October 2003 and continued fighting an insurgency that would eventually spread to other countries in the region.[37][38]

History[edit]

Background[edit]

Social conditions that led to dissatisfaction with the FLN government, and interest in jihad against it include: a population explosion in the 1960s and 70s that outstripped the stagnant economy's ability to supply jobs, housing, food and urban infrastructure to massive numbers of young in the urban areas;[Note 2] a collapse in the price of oil,[Note 3] whose sale supplied 95% of Algeria's exports and 60% of the government's budget;[39] a single-party state ostensibly based on socialism, anti-imperialism, and popular democracy, but ruled by high-level military and party nomenklatura from the east side of the country;[39] "corruption on a grand scale";[39] underemployed Arabic-speaking college graduates frustrated that the "Arab language fields of law and literature took a decisive back seat to the French-taught scientific fields in terms of funding and job opportunities";[41] and in response to these issues, "the most serious riots since independence" occurring in October 1988 when thousands of urban youth (known as hittistes) took control of the streets despite the killing of hundreds by security forces.[39]

Islam in Algeria after independence was dominated by Salafist "Islamic revivalism" and political Islam rather than the more apolitical popular Islam of brotherhoods found in other areas of North Africa. The brotherhoods had been dismantled by the FLN government in retaliation for lack of support and their land had been confiscated and redistributed by the FLN government after independence.[42] In the 1980s the government imported two renowned Islamic scholars, Mohammed al-Ghazali and Yusuf al-Qaradawi, to "strengthen the religious dimension" of the ruling National Liberation Front (FLN) party's "nationalist ideology". Rather than doing this, the clerics worked to promote "Islamic awakening" as they were "fellow travelers" of the Muslim Brotherhood and supporters of Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf monarchies.[43] Al-Ghazali issuing a number of fatawa (Islamic judicial rulings) favorable to positions taken by local "radical" imams.[41]

Another Islamist, Mustafa Bouyali, a "gifted inflammatory preacher" and veteran of the Algerian independence struggle, called for the application of the sharia and creating of an Islamic state by jihad. After persecution by the security services in 1982 he founded the underground Mouvement Islamique Armé (MIA), "a loose association of tiny groups", with himself as amir. His group carried out a series of "bold attacks" against the regime and was able to continue its fight for five years before Bouyali was killed in February 1987.[44]

Also in the 1980s, several hundred youth left Algeria for camps of Peshawar to fight jihad in Afghanistan. As Algeria was a close ally of the jihadists enemy the Soviet Union, these jihadists tended to consider the Afghan jihad a "prelude" to jihad against the Algerian FLN state.[45] After the Marxist government in Afghanistan fell, many of the Salafist-Jihadis returned to Algeria and supported the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) and later the GIA insurgents.[45]

During and after the 1988 October Riots Islamists "set about building bridges to the young urban poor". Evidence of their effectiveness was that the riots "petered out" after meetings between the President Chadli Bendjedid and Islamists Ali Benhadj and members of the Muslim Brotherhood.[46]

The FLN government responded to the riots by amending the Algerian Constitution on 3 November 1988, to allow parties other than the ruling FLN to operate legally. A broad-based Islamist party, the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) was born shortly afterwards in Algiers on 18 February 1989, and came into legal existence in September 1989.[47] The front was led by two men. Abbassi Madani—a professor at University of Algiers and ex-independence fighter—represented a relatively moderate religious conservatism and symbolically connected the party to the Algerian War of Independence, the traditionally emphasized source of the ruling FLN's legitimacy. His aim was to "Islamise the regime without altering society's basic fabric."[46] Ali Benhadj, a charismatic preacher and high school teacher appealed to a younger and less educated class. An impassioned orator, he was known for his ability to both enrage or calm at will the tens of thousands of young hittiestes who came to hear him speak. However, his radical speeches and opposition to democratic rule alarmed non-Islamists and feminists. Neither Madani or Benhadj were committed to democracy.

In December 1989 Madani was quoted as saying:

and in February 1989, Benhadj stated:

The FIS made "spectacular" progress in the first year of its existence,[46] with an enormous following in the urban areas. Its doctors, nurses and rescue teams showed "devotion and effectiveness" helping victims of an earthquake in Tipaza Province;[47] its organized marches and rallies "applied steady pressure on the state" to force a promise of early elections.[47]

FIS electoral victory, 1990[edit]

Despite President Bendjedid and his party, the FLN's new liberal reforms, in the 12 June 1990 local elections—the first free elections since independence—the Algerian voters chose the FIS. The party won 54% of votes cast, almost double that of the FLN and far more than any of the other parties.[52] Its supporters were especially concentrated in urban areas.[53]

Once in power in local governments, its administration and its Islamic charity were praised by many as just, equitable, orderly and virtuous, in contrast to its corrupt, wasteful, arbitrary and inefficient FLN predecessors.[54][55] But it also alarmed the less-traditional educated French-speaking class. It imposed the veil on female municipal employees; pressured liquor stores, video shops and other un-Islamic establishments to close; and segregated bathing areas by gender.[56]

Co-leader of the FIS Ali Benhadj declared his intention in 1990, "to ban France from Algeria intellectually and ideologically, and be done, once and for all, with those whom France has nursed with her poisoned milk."[56][57]

Devout activists removed the satellite dishes of households receiving European satellite broadcast in favor of Arab satellite dishes receiving Saudi broadcasts.[58] Educationally, the party was committed to continue the Arabization of the educational system by shifting the language of instruction in more institutions, such as medical and technological schools, from French to Arabic. Large numbers of recent graduates, the first post-independence generation educated mainly in Arabic, liked this measure, as they had found the continued use of French in higher education and public life jarring and disadvantageous.[59]

In January 1991 following the start of the Gulf War, the FIS led giant demonstrations in support of Saddam Hussein and Iraq. One demonstration ended in front of the Ministry of Defense where radical leader Ali Benhadj gave an impassioned speech demanding a corp of volunteers be sent to fight for Saddam. The Algerian military took this as a direct affront to the military hierarchy and cohesion. After a project to realign electoral districts came to light in May, the FIS called for a general strike. Violence ensued and on 3 June 1991 a state of emergency was declared, many constitutional rights were suspended, and parliamentary elections postponed until December. The FIS began to lose the initiative and within a month the two leaders (Mandani and Benhadj) of the FIS were arrested and later sentenced to twelve years in prison.[59] Support for armed struggle began to develop among Bouyali's followers and veterans of the Afghan jihad and on 28 November the first act of jihad against the government occurred when a frontier post (at Guemmar) was attacked and the heads of army conscripts were cut off.[60] Despite this the FIS participated in the legislative elections and on 26 December 1991 won the first round with 118 deputies elected as opposed to just 16 for the FLN.[60] despite getting one million fewer votes than it had in 1990 elections. It appeared to be on track to win an absolute majority in the second round on 13 January 1992.

Military coup and cancellation of elections, 1992[edit]

The FIS had made open threats against the ruling pouvoir, condemning them as unpatriotic and pro-French, as well as financially corrupt. Additionally, FIS leadership was at best divided on the desirability of democracy, and some expressed fears that a FIS government would be, as U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Edward Djerejian put it, "one person, one vote, one time."[61]

On 11 January 1992 the army cancelled the electoral process, forcing President Bendjedid to resign and bringing in the exiled independence fighter Mohamed Boudiaf to serve as a new president. However, on 29 June 1992 he was assassinated by one of his bodyguards, Lieutenant Lambarek Boumaarafi. The assassin was sentenced to death in a closed trial in 1995. The sentence was not carried out. So many FIS members were arrested—5,000 by the army's account, 40,000 according to Gilles Kepel[62] and including its leader Abdelkader Hachani—that the jails had insufficient space to hold them in; camps were set up for them in the Sahara desert, and bearded men feared to leave their houses lest they be arrested as FIS sympathizers. The government officially dissolved the FIS on 4 March and its apparatus was dismantled.[60]

Beginning of war, 1992–93[edit]

Of the few FIS activists that remained free, many took this as a declaration of war. Throughout much of the country, remaining FIS activists, along with some Islamists too radical for FIS, took to the hills (the mountains of northern Algeria, where the forest and scrub cover were well-suited to guerrilla warfare) with whatever weapons were available and became guerrilla fighters. The very sparsely populated but oil-rich Sahara would remain mostly peaceful for almost the entire duration of the conflict. This meant that the government's principal source of foreign exchange—oil exports—was largely unaffected.[citation needed] The tense situation was compounded by the economy, which collapsed even further that year, as almost all of the longstanding subsidies on food were eliminated.

At first Algeria remained relatively calm. But in March 1993 "a steady succession of university academics, intellectuals, writer, journalist, and medical doctors were assassinated."[63] While not all were connected with the regime, they were French-speaking and so "in the eyes of the young urban poor who had joined the jihad ... associated with the hated image of French-speaking intellectuals".[63] It also "exploded" the idea of the government's triumph over the Islamists. Other attacks showed a willingness to target civilians. The bombing of the Algiers airport claimed 9 lives and injured 128 people. The FIS condemned the bombing along with the other major parties, but the FIS's influence over the guerrillas turned out to be limited.[63]

The regime began to lose control of mountain and rural districts. In working class areas of the cities insurgents expelled the police and declared "liberated Islamic zones".[63] Even the main roads of the cities passed into the hands of the insurgents.[63]

Founding of the insurgent groups[edit]

The first major armed movement to emerge, starting almost immediately after the coup, was the Islamic Armed Movement (MIA). The group was founded by former militants of Mustafa Bouyali "group" such as Abdelkader Chebouti, Mansouri Meliani, and Ezzedine Baa and they named themselves after his group active in the 80's. It was led by the ex-soldier "General" Abdelkader Chebouti, a longstanding Islamist. The MIA was "well-organized and structured and favored a long-term jihad" targeting the state and its representatives and based on a guerrilla campaign like that of the War of Independence.[64] From prison, Ali Benhadj issued a fatwa giving the MIA his blessing.[64] In February 1992, ex-Algerian officer, ex-Afghan fighter, former FIS head of security and editor of the FIS official newspaper El Mounqid, Said Mekhloufi founded the Movement for an Islamic State (MEI).

The other main jihad group was called the Armed Islamic Group (GIA, from French Groupe Islamique Armé). In January 1993, Abdelhak Layada declared his group independent of Chebouti's. It became particularly prominent around Algiers and its suburbs, in urban environments. It took a hardline position, opposed to both the government and the FIS, affirming that "political pluralism is equivalent to sedition"[65][66] and issuing death threats against several FIS and MIA leaders. It favored a strategy of "immediate action to destabilize the enemy", by creating "an atmosphere of general insecurity" through "repeated attacks". It considered opposition to violence among some in the FIS as not only misguided but impious.[64] It was far less selective than the MIA, which insisted on ideological training; as a result, it was regularly infiltrated by the security forces, resulting in a rapid leadership turnover as successive heads were killed.

The various groups arranged several meetings to attempt to unite their forces, accepting the overall leadership of Chebouti in theory. At the last of these, at Tamesguida on 1 September, Chebouti expressed his concern about the movement's lack of discipline, in particular worrying that the Algiers airport attack, which he had not approved, could alienate supporters. The meeting was broken up by an assault from the security forces, provoking suspicions which prevented any further meetings. However the MEI merged with the GIA in May 1994.

The FIS itself established an underground network, with clandestine newspapers and even an MIA-linked radio station, and began issuing official statements from abroad starting in late 1992. However, at this stage the opinions of the guerrilla movements on the FIS were mixed; while many supported FIS, a significant faction, led by the "Afghans", regarded party political activity as inherently un-Islamic, and therefore rejected FIS statements.[citation needed]

In 1993, the divisions within the guerrilla movement became more distinct. The MIA and MEI, concentrated in the maquis, attempted to develop a military strategy against the state, typically targeting the security services and sabotaging or bombing state institutions. From its inception on, however, the GIA, concentrated in urban areas, called for and implemented the killing of anyone supporting the authorities, including government employees such as teachers and civil servants. It assassinated journalists and intellectuals (such as Tahar Djaout), saying that "The journalists who fight against Islamism through the pen will perish by the sword."[67]

It soon stepped up its attacks by targeting civilians who refused to live by their prohibitions, and in September 1993 began killing foreigners,[68] declaring that "anyone who exceeds" the GIA deadline of 30 November "will be responsible for his own sudden death."[69] 26 Foreigners were killed by the end of 1993[70] and virtually all foreigners left the country; indeed, (often illegal) Algerian emigration too rose substantially, as people sought a way out. At the same time, the number of visas granted to Algerians by other countries began to drop substantially.

Failed negotiations and guerrilla infighting, 1994[edit]

The violence continued throughout 1994, although the economy began to improve during this time; following negotiations with the IMF, the government succeeded in rescheduling debt repayments, providing it with a substantial financial windfall,[71] and further obtained some 40 billion francs from the international community to back its economic liberalization.[72] As it became obvious that the fighting would continue for some time, General Liamine Zéroual was named new president of the High Council of State; he was considered to belong to the dialoguiste (pro-negotiation) rather than éradicateur (eradicator) faction of the army.

Soon after taking office, he began negotiations with the imprisoned FIS leadership, releasing some prisoners by way of encouragement. The talks split the pro-government political spectrum. The largest political parties, especially the FLN and FFS, continued to call for compromise, while other forces—most notably the General Union of Algerian Workers (UGTA), but including smaller leftist and feminist groups such as the secularist RCD—sided with the "eradicators". A few shadowy pro-government paramilitaries, such as the Organisation of Young Free Algerians (OJAL), emerged and began attacking civilian Islamist supporters. On 10 March 1994, over 1000 (mainly Islamist) prisoners escaped Tazoult prison in what appeared to be a major coup for the guerrillas; later, conspiracy theorists would suggest that this had been staged to allow the security forces to infiltrate the GIA.

Meanwhile, under Cherif Gousmi (its leader since March), the GIA became the most high-profile guerrilla army in 1994, and achieved supremacy over the FIS.[68] In May, several Islamist leaders that were not jailed (Mohammed Said, Abderraraq Redjem), including the MEI's Said Makhloufi, joined the GIA. This was a surprise to many observers, and a blow to the FIS since the GIA had been issuing death threats against the leaders since November 1993. The move was interpreted either as the result of intra-FIS competition or as an attempt to change the GIA's course from within.[68]

FIS-loyal guerrillas, threatened with marginalization, attempted to unite their forces.[73] In July 1994,[73] the MIA, together with the remainder of the MEI and a variety of smaller groups,[citation needed] united as the Islamic Salvation Army (a term that had previously sometimes been used as a general label for pro-FIS guerrillas), declaring their allegiance to FIS. It national amir was Madani Merzag.[73] By the end of 1994, they controlled over half the guerrillas of the east and west, but barely 20% in the center, near the capital, which was where the GIA were mainly based. They issued communiqués condemning the GIA's indiscriminate targeting of women, journalists and other civilians "not involved in the repression", and attacked the GIA's school arson campaign. The AIS and FIS supported a negotiated settlement with the government/military, and the AIS's role was to strengthening FIS's hand in the negotiations.[73] The GIA was absolutely opposed to negotiations and sought instead "to purge the land of the ungodly", including the Algerian government. The two insurgent groups would soon be "locked in bloody combat."[73]

Despite the growing power of the GIA, inside the "liberated Islamic zones" of the insurgency, conditions were beginning to deteriorate. The Islamist notables, entrepreneurs, and shopkeepers had at first funded the insurgent amirs and fighters, hoping for revenge against the government that had seized power from the FIS movement they supported. But over the months the voluntary "Islamic tax" became a "full-scale extortionist racket, operated by band of armed men claiming to represent an ever more shadowy cause," who also fought each other over turf. The extortion and the fact that the zones were surrounded by the army, impoverished and victimized the pious business class which eventually fled the zones, severely weakening the Islamist cause.[68]

On 26 August, the GIA even declared a caliphate, or Islamic government, for Algeria, with Gousmi as "Commander of the Faithful".[74] However, the very next day, Said Mekhloufi announced his withdrawal from the GIA, claiming that the GIA had deviated from Islam and that this caliphate was an effort by ex-FIS leader Mohammed Said to take over the GIA. The GIA continued attacks on its usual targets, notably assassinating artists, such as Cheb Hasni, and in late August added a new practice to its activities: threatening insufficiently Islamist schools with arson.

At the end of October, the government announced the failure of its negotiations with the FIS. Instead, Zéroual embarked on a new plan: he scheduled presidential elections for 1995, while promoting "eradicationists" such as Lamari within the army and organizing "self-defense militias" in villages to fight the guerrillas. The end of 1994 saw a noticeable upsurge in violence. Over 1994, Algeria's isolation deepened; most foreign press agencies, such as Reuters, left the country this year, while the Moroccan border closed and the main foreign airlines cancelled all routes. The resulting gap in news coverage was further worsened by a government order in June banning Algerian media from reporting any terrorism-related news not covered in official press releases.[75]

A few FIS leaders, notably Rabah Kebir, had escaped into exile abroad. Upon the invitation of the Rome-based Community of Sant'Egidio, in November 1994, they began negotiations in Rome with other opposition parties, both Islamist and secular (FLN, FFS, FIS, MDA, PT, JMC). They came out with a mutual agreement on 14 January 1995: the Sant'Egidio platform. This presented a set of principles: respect for human rights and multi-party democracy, rejection of army rule and dictatorship, recognition of Islam, Arab and Berber ethnic identity as essential aspects of Algeria's national identity, demand for the release of FIS leaders, and an end to extrajudicial killing and torture on all sides.

To the surprise of many, even Ali Belhadj endorsed the agreement, which meant that the FIS had returned into the legal framework, along with the other opposition parties. The initiative was also received favorably by "influential circles" in the United States. However, for the agreement to work, the FIS still had to have the support of its original power base, when in fact the pious bourgeous had abandon it for the collaborationist Hamas party and the urban poor for jihad;[76] and the other side, the government, had to be interested in the agreement. Those two features being lacking, the platform's effect was at best limited – though some argue that, in the words of Andrea Riccardi who brokered the negotiations for the Community of Sant'Egidio, "the platform made the Algerian military leave the cage of a solely military confrontation and forced them to react with a political act", the 1995 presidential elections. The next few months saw the killing of some 100 Islamist prisoners in the Serkadji prison mutiny, and a major success for the security forces in the battle of Ain Defla, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of guerrilla fighters.

Cherif Gousmi was eventually succeeded by Djamel Zitouni as GIA head. Zitouni extended the GIA's attacks on civilians to French soil, beginning with the hijacking of Air France Flight 8969 at the end of December 1994 and continuing with several bombings and attempted bombings throughout 1995. It is thought Zitouni hoped to undermine the FIS by proving its irrelevance to the outcome of the war,[77] and to induce the French government to withdraw support from the Algerian government to put a stop to the terrorism.[78] But by eliminating the FIS as a factor the campaign also suggested to outsiders in America and Europe that the "only force capable of stopping the terrorists" was the Algerian government.[77] In any case, in France the GIA attacks created a backlash of fear of young Muslim immigrants joining the campaign.[78] The campaign was a major fault line dividing the insurgents. The GIA "exalted in the enthusiasm of the disinherited" poor young Algerian men every time "the former colonial power" was attacked, while the FIS leaders abroad struggled to persuade "the governments of Europe and the United States" that Islamic FIS government would "guarantee social order and expand the market economy" in Algeria.[79]

In Algeria itself, attacks continued, with car bombs and assassinations of musicians, sportsmen, and unveiled women, as well as police and soldiers. Even at this stage, the seemingly counterproductive nature of many of its attacks led to speculation (encouraged by FIS members abroad whose importance was undermined by GIA hostility to negotiation) that the group had been infiltrated by Algerian secret services. The region south of Algiers, in particular, came to be dominated by the GIA, who called it the "liberated zone". Later, it would come to be known as the "Triangle of Death".

Reports of battles between the AIS and GIA increased, and the GIA reiterated its death threats against FIS and AIS leaders, assassinating a co-founder of the FIS, Abdelbaki Sahraoui, in Paris. At this point, foreign sources estimated the total number of guerrillas to be about 27,000.

Politics resume, militias emerge, 1995–96[edit]

Following the breakdown of negotiations with the FIS, the government decided to hold presidential elections. On 16 November 1995, former head of ground forces of the Algerian military Liamine Zéroual was elected president with 60% of votes cast in an election contested by many candidates. The results reflected various popular opinions, ranging from support for secularism and opposition to Islamism to a desire for an end to the violence, regardless of politics. The FIS had urged Algerians to boycott the election and the GIA threatened to kill anyone who voted (using the slogan "one vote, one bullet"), but turnout was relatively high among the pious middle class who had formerly supported the FIS but become disillusioned by the "endless violence and racketeering by gangs of young men in the name of jihad."[79] and turned out for Islamists Mahfoud Nahnah (25%) and Noureddine Boukrouh.[80] Hopes grew that Algerian politics would finally be normalized. Zéroual followed this up by pushing through a new constitution in 1996, substantially strengthening the power of the President and adding a second house that would be partly elected and partly appointed by the President. In November 1996, the text was passed by a national referendum; while the official turnout rate was 80%, this vote was unmonitored, and the claimed high turnout was considered by most to be implausible.

The election results were a setback for the armed groups, who saw a significant increase in desertions immediately following the elections. The FIS' Rabah Kebir responded to the apparent shift in popular mood by adopting a more conciliatory tone towards the government, but was condemned by some parts of the party and of the AIS. The GIA was shaken by internal dissension; shortly after the election, its leadership killed the FIS leaders who had joined the GIA, accusing them of attempting a takeover. This purge accelerated the disintegration of the GIA: Mustapha Kartali, Ali Benhadjar and Hassan Hattab's factions all refused to recognize Zitouni's leadership starting around late 1995, although they would not formally break away until later. In December, the GIA killed the AIS leader for central Algeria, Azzedine Baa, and in January pledged to fight the AIS as an enemy; particularly in the west, full-scale battles between them became common.

The Government's political moves were combined with a substantial increase in the pro-Government militias' profile. "Self-defense militias", often called "Patriots" for short, consisting of trusted local citizens trained and armed by the army, were founded in towns near areas where guerrillas were active, and were promoted on national TV. The program was received well in some parts of the country, but was less popular in others; it would be substantially increased over the next few years, particularly after the massacres of 1997.

Massacres and reconciliation, 1996–97[edit]

In July 1996 GIA leader, Djamel Zitouni was killed by one of the breakaway ex-GIA factions and was succeeded by Antar Zouabri, who would prove an even bloodier leader.

1997 elections[edit]

Parliamentary elections were held on 5 June 1997. They were dominated by the National Democratic Rally (RND), a new party created in early 1997 for Zéroual's supporters, which got 156 out of 380 seats, followed mainly by the MSP (as Hamas had been required to rename itself) and the FLN at over 60 seats each. Views on this election were mixed; most major opposition parties filed complaints, and that a party (RND) founded only a few months earlier and which had never taken part in any election before should win more votes than any other seemed implausible to observers.[citation needed] The RND, FLN and MSP formed a coalition government, with the RND's Ahmed Ouyahia as prime minister. There were hints of a softening towards FIS: Abdelkader Hachani was released, and Abbassi Madani moved to house arrest.

Village massacres[edit]

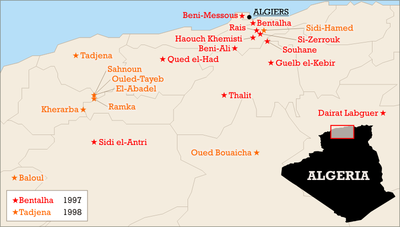

At this point, however, a new and vital problem emerged. Starting around April (the Thalit massacre), Algeria was wracked by massacres of intense brutality and unprecedented size; previous massacres had occurred in the conflict, but always on a substantially smaller scale. Typically targeting entire villages or neighborhoods and disregarding the age and sex of victims, killing tens, and sometimes hundreds, of civilians at a time.

| Algerian massacres in 1997 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Massacres in which over 50 people were killed: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1998 → | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Algerian massacres in 1998 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Massacres in which over 50 people were killed: | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

← 1997 1999 → | ||||||||||

These massacres continued through the end of 1998, changing the nature of the political situation considerably. The areas south and east of Algiers, which had voted strongly for FIS in 1991, were hit particularly hard; the Rais and Bentalha massacres in particular shocked worldwide observers. Pregnant women were sliced open, children were hacked to pieces or dashed against walls, men's limbs were hacked off one by one, and, as the attackers retreated, they would kidnap young women to keep as sex slaves. Although this quotation by Nesroullah Yous, a survivor of Bentalha, may be an exaggeration, it expresses the apparent mood of the attackers:

Dispute over responsibility[edit]

The GIA's responsibility for these massacres remains disputed. In a communique its amir Antar Zouabri claimed credit for both Rais and Bentalha, calling the killings an "offering to God" and declaring impious the victims and all Algerians who had not joined its ranks.[82] By declaring that "except for those who are with us, all others are apostates and deserving of death,"[83] it had adopted a takfirist ideology. In some cases, it has been suggested that the GIA were motivated to commit a massacre by a village's joining the Patriot program, which they saw as evidence of disloyalty; in others, that rivalry with other groups (e.g., Mustapha Kartali's breakaway faction) played a part. Its policy of massacring civilians was cited by the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat as one of the main reasons it split off from the GIA.

However, according to reports by Amnesty International[84] and Human Rights Watch[85] army barracks were stationed within a few hundred meters of the villages, yet did nothing to stop the killings. At about the same time, a number of people claiming to be defectors from the Algerian security services (such as Habib Souaidia), having fled to Western countries, alleged that the security services had themselves committed some of the massacres.[86][87][88] [89][page needed][Note 4] These and other details raised suspicions that the state was in some way collaborating with, or even controlling parts of, the GIA (particularly through infiltration by the secret services) – a theory popularised by Nesroullah Yous, and FIS itself.[91] This suggestion provoked furious reactions from some quarters in Algeria, and has been rejected by many researchers,[Note 5] though others regard it as plausible. [Note 6]

In contrast, Algerians such as Zazi Sadou, have collected testimonies by survivors that their attackers were unmasked and were recognised as local radicals – in one case even an elected member of the FIS.[Note 7] Roger Kaplan, writing in The Atlantic Monthly, dismissed insinuations of Government involvement in the massacres;[Note 8] However, as Youcef Bouandel notes; "Regardless of the explanations one may have regarding the violence, the authorities' credibility has been tarnished by its non-assistance to endangered civilian villagers being massacred in the vicinity of military barracks. "[96] Another explanation is the "deeply ingrained" tradition of "purposeful accumulation of wealth and status by means of violence",[97] outweighing any basic national identity with feelings of solidarity, loyalty, for what was a province of the Ottoman Empire for much of its history.

AIS unilateral truce[edit]

The AIS, which at this point was engaged in an all-out war with the GIA as well as the Government, found itself in an untenable position. The GIA seemed a more immediately pressing enemy, and AIS members expressed fears that the massacres—which it had condemned more than once—would be blamed on them. On 21 September 1997, the AIS' head, Madani Mezrag, ordered a unilateral and unconditional ceasefire starting 1 October, in order to "unveil the enemy that hides behind these abominable massacres." The AIS thus largely took itself out of the political equation, reducing the fighting to a struggle between the Government, the GIA, and the various splinter groups that were increasingly breaking away from the GIA. Ali Benhadjar's FIS-loyalist Islamic League for Da'wa and Jihad (LIDD), formed in February 1997, allied itself with the AIS and observed the same ceasefire. Over the next three years, the AIS would gradually negotiate an amnesty for its members.

GIA destroyed, 1998–2000[edit]

| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

After receiving much international pressure to act, the EU sent two delegations, one of them led by Mário Soares, to visit Algeria and investigate the massacres in the first half of 1998; their reports condemned the Islamist armed groups.

The GIA's policy of massacring civilians had already caused a split among its commanders, with some rejecting the policy; on 14 September 1998, this disagreement was formalized with the formation of the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC), based in the mountains west of Kabylie and led by Hassan Hattab. Massacres continued throughout 1998 attributed to "armed groups that had formerly belonged to the GIA", some engaged in banditry, other settling scores with the patriots or others, some enlisting in the services of landowners to frighten illegal occupants away.[98] Eventually towns soon became safer, although massacres continued in rural areas.[citation needed]

On 11 September, President Zéroual surprised observers by announcing his resignation. New elections were arranged, and on 15 April 1999, the army-backed ex-independence-fighter Abdelaziz Bouteflika was elected president with, according to the authorities, 74% of the votes. All the other candidates had withdrawn from the election shortly before, citing fraud concerns. Bouteflika continued negotiations with the AIS, and on 5 June the AIS agreed, in principle, to disband. Bouteflika followed up this success for the Government by pardoning a number of Islamist prisoners convicted of minor offenses and pushing the Civil Harmony Act through Parliament, a law allowing Islamist fighters not guilty of murder or rape to escape all prosecution if they turn themselves in.[citation needed]

This law was finally approved by referendum on 16 September 1999, and a number of fighters, including Mustapha Kartali, took advantage of it to give themselves up and resume normal life—sometimes angering those who had suffered at the hands of the guerrillas. FIS leadership expressed dissatisfaction with the results, feeling that the AIS had stopped fighting without solving any of the issues; but their main voice outside of prison, Abdelkader Hachani, was assassinated on 22 November. Violence declined, though not stopping altogether, and a sense of normality started returning to Algeria.[citation needed]

The AIS fully disbanded after 11 January 2000, having negotiated a special amnesty with the Government. The GIA, torn by splits and desertions and denounced by all sides even in the Islamist movement, was slowly destroyed by army operations over the next few years; by the time Algerian security forces killed Antar Zouabri in Boufarik on 8 February 2002, it was effectively incapacitated. The Government's efforts were given a boost in the aftermath of 11 September 2001 attacks; United States sympathy for Algeria's government increased, and was expressed concretely through such actions as the freezing of GIA and GSPC assets and the supply of infrared goggles to the army.[citation needed]

GSPC continues[edit]

With the GIA's decline, the GSPC was left as the most active rebel group, with about 300 fighters in 2003.[99] It continued a campaign of assassinations of police and army personnel in its area, and also managed to expand into the Sahara, broadening the conflict into the insurgency in the Maghreb (2002–present). Its southern division, led by Amari Saifi (nicknamed "Abderrezak el-Para", the "paratrooper"), kidnapped a number of German tourists in 2003, before being forced to flee to sparsely populated areas of Mali, and later Niger and Chad, where he was captured. By late 2003, the group's founder had been supplanted by the even more radical Nabil Sahraoui, who announced his open support for al-Qaeda, thus strengthening government ties between the U.S. and Algeria. He was reportedly killed shortly afterwards, and was succeeded by Abou Mossaab Abdelouadoud in 2004.[100]

2004 presidential election and amnesty[edit]

The release of FIS leaders Madani and Belhadj in 2003 had no observable effect on the situation, illustrating a newfound governmental confidence which would be deepened by the 2004 presidential election, in which Bouteflika was reelected by 85% with support from two major parties and one faction of the third major party. The vote was seen as confirming strong popular support for Bouteflika's policy towards the guerrillas and the successful termination of large-scale violence.[citation needed]

In September 2005 a national referendum was held on an amnesty proposal by Bouteflika's government, similar to the 1999 law, to end legal proceedings against individuals who were no longer fighting, and to provide compensation to families of people killed by Government forces. The controversial Charter for Peace and National Reconciliation was declared to have won with 97% support, and with 80% of participation.[101] The conditions of the campaign in Algeria were criticized in the French press, in particular in Le Monde and L'Humanité.[citation needed]

Lawyer Ali Merabet, for example, founder of Somoud, an NGO which represents the families of the disappeared, was opposed to the Charter which would "force the victims to grant forgiveness". He remains doubtful that the time of the FIS has truly ended and notes that while people no longer support them, the project of the FIS – which he denies is Islamic – still exists and remains a threat.[102]

The proposal was implemented by Presidential decree in February 2006, and adopted on 29 September 2006. Particularly controversial was its provision of immunity against prosecution to surrendered ex-guerrillas (for all but the worst crimes) and Army personnel (for any action "safeguarding the nation".)[103] According to Algerian paper El Khabar, over 400 GSPC guerrillas surrendered under its terms.[104] Estimates of the rebels size in 2005 ranged from 300 to 1000.[105] The International Federation of Human Rights (FIDH) has opposed the amnesty.[106]

While the fighting died down a state of emergency remained in place,[107] only being lifted in February 2011 due to renewed protests amidst the ongoing Arab Spring.

Death toll[edit]

Bouteflika said in 1999 that 100,000 people had died by that time and in a speech on 25 February 2005, spoke of a round figure of 150,000 people killed in the war.[105] Fouad Ajami argues the toll could be as high as 200,000, and that it is in the government's interest to minimize casualties.[35] These figures, not broken down into government forces, insurgents and civilians, are commonly cited as the war's death toll. However this estimate may be too high. A 2008 study found about 26,000 people killed, through combat operations, massacres, bombings and assassinations, alongside 18,000 people, 'disappeared' and presumed killed in secret. This would give a total death toll of around 44,000 people.[34] This is out of a population of about 25,010,000 in 1990 and 31,193,917 in 2000.[34][108]

Use of children[edit]

Throughout the war children were recruited frequently by the armed groups fighting the government.[33] A government-allied militia—the Legitimate Defence Groups (LDG)—also used children, according to some reports.[33][109] Although the rules for joining the LDG were the same as the army, in which only adults were recruited (by conscription) the LDG applied no safeguards to ensure that children could not join up.[109] The extent of child recruitment during the war remains unknown.[109]

Analysis and impact[edit]

Factors that prevented Algeria from following in the path of Saudi Arabia and Iran into an Islamic state include minority groups (army rank and file, veterans of the War of Independence, the secular middle class) that threw their support with the government, and Islamist supporters that lost faith with the Salafi Jihadis. Unlike in Iran, the army rank and file stayed on the side of the government. Veterans of the War of Independence known as the "revolutionary family" felt its privileges directly tied to the government and supported the regime. Also unlike in Iran, the secular middle class remained firmly in support of the government. Branded as "sons of France" by the jihadis, they feared an Islamist takeover far more than they hated the corruption and ineptitude of the FLN government.[110] The part of the middle class who supported the FIS supported the jihad against the government at first. However, living in GIA-controlled areas, cut off by the security forces, they suffered from extortion from less-than-disciplined young jihadis demanding "Zakat". Business owners abandoned the GIA to support first the AIS and eventually the government-approved Islamist Hamas or Movement of Society for Peace party.[68] The young urban poor themselves whose 1988 October Riots had initiated reforms and put an end to one-party rule, was "crushed as a political factor".[111]

At least at first, the "unspeakable atrocities" and enormous loss of life on behalf of a military defeat "drastically weakened Islamism as a whole" throughout the Muslim world, and led to much time and energy being spent by Islamists distancing themselves from extremism.[112] In Algeria the war left the public "with a deep fear of instability" according to Algerian journalist Kamel Daoud. The country was one of the few in the Arab world not to participate in the Arab Spring.[113]

See also[edit]

- List of Algerian assassinated journalists

- Terrorist bombings in Algeria

- Garde communale

- Algerian War

- Censorship in Algeria

- Human rights in Algeria

- Les éradicateurs – Les dialoguistes

- Sant'Egidio platform

- Timeline of the Algerian Civil War

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Hassan Hattab's GSPC which has condemned the GIA's indiscriminate attacks on civilians and, since going it alone, has tended to revert to the classic MIA-AIS strategy of confining its attacks to guerrilla forces."[36]

- ^ In 1989, 40 percent of Algeria's population of 24 million were under 15 years of age; the urban population was in excess of 50 percent of the total population; the birthrate was 3.1% per year[39]

- ^ price fell from over US$35 per barrel in 1980 to below $10 in 1986 (prices not adjusted for inflation)[40]

- ^ "'When I enlisted into the Algerian army in 1989, I was miles away from thinking that I would be a witness to the tragedy that has struck my country. I have seen colleagues burn alive a 15-year-old child. I have seen soldiers disguising themselves as terrorists and massacring civilians."[90]

- ^ "Still, there is substantial evidence that many among the deadliest massacres have been perpetrated by Islamist guerrillas. The most important evidence comes from testimonies of survivors who were able to identify local Islamists among the attackers (see below). In fact, survivors who openly accuse the army for its failure to intervene also expressed no doubt about the identity of the killers, pointing to the Islamist guerrillas (e.g. Tuquoi, J.-P. 1997. 'Algérie, Autopsie d'un Massacre.' Le Monde 11 November). Moreover, some of the troubling aspects of this story can be explained without reference to an army conspiracy. For example, in civil wars prisoners tend to be killed on the spot rather than taken prisoner (Laqueur, W. 1998. Guerrilla Warfare: A Historical and Critical Study. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction). Militiamen, the most likely to capture guerrillas, have openly stated that they took no prisoners (Amnesty International. 1997b. Algeria: Civilian Population Caught in a Spiral of Violence. Report MDE 28/23/97. p.17). Journalists working in the field have found credible testimonies in support of the thesis that most massacres are organized by the rebels (Leclère, T. 1997. 'Raïs, Retour sur un Massacre.' Télérama 22 October; Tuquoi 1997 among others). European foreign ministries believe that it is Islamist guerrillas who are responsible for the massacres (Observer 9 February 1998). Although, it is impossible to know the full truth at this point (see Charef, A. 1998. Algérie: Autopsie d'un massacre. Paris: L'Aube.), the assumption that many massacres were committed by the Islamist guerrillas seems plausible and is widely adopted by area experts (Addi, L. 1998. 'Algeria's Army, Algeria's Agony.' Foreign Affairs (July–August), p.44) and other authors (Smith, B. 1998. 'Algeria: The Horror.' The New York Review of Books XLV 7: p.27). Likewise, the reluctance of the army to intervene and stop some of these massacres is also beyond doubt."[92]

- ^ "Under Zouabri, the extremism and violence of the GIA became completely indiscriminate, leading to the horrific massacres of 1997 and 1998 – although, once again, great care must be exercised over these incidents as it is quite clear that the greatest beneficiary from them was the Algerian state. There is considerable indirect evidence of state involvement and some direct evidence as well, which is discussed below."[93]

- ^ "Some fundamentalist leaders have attempted to distance themselves from these massacres and claimed that the State was behind them or that they were the work of the State-armed self-defense groups. Some human rights groups have echoed this claim to some extent. Inside Algeria, and particularly among survivors of the communities attacked, the view is sharply different. In many cases, survivors have identified their attackers as the assailants enter the villages unmasked and are often from the locality. In one case, a survivor identified a former elected FIS officials as one of the perpetrators of a massacre. Testimonies Collected by Zazi Sadou."[94]

- ^ "To people who had been watching Algeria's evolution, the assumption that sinister complicities within the Algerian state were involved in the assassinations and massacres was libelous. I thought of Khalida Messaoudi, a forty-year-old former teacher and political activist who went into hiding after being sentenced to die by those who shared the ideology of the killers who descended on Had T'Chekala. Among democratic, human rights, and feminist organizations very few have expressed support for Messaoudi. In the United States only the American Federation of Teachers has recognized her struggle for human rights. She was condemned for being an impious, Zionist (she is a nonpracticing Muslim), loose, radical woman, and thousands of women in Algeria have been killed for much less. Sixteen-year-old girls, for instance, have been dragged out of classrooms and slaughtered in school yards like sheep because the killers decreed that nubile girls should not be in school. This was the context and the background and the reality. And now, when the world paid attention, it was to suggest the involvement of Government death squads."[95]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Paul Collier; Nicholas Sambanis (2005). Understanding Civil War: Africa. World Bank Publications. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-8213-6047-7.

- ^ a b Rex Brynen; Bahgat Korany; Paul Noble (1995). Political Liberalization and Democratization in the Arab World. Vol. 1. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-55587-579-4.

- ^ a b c d e Sidaoui, Riadh (2009). "Islamic Politics and the Military: Algeria 1962–2008". In Jan-Erik Lane; Hamadi Redissi; Riyāḍ Ṣaydāwī (eds.). Religion and Politics: Islam and Muslim Civilization. Ashgate. pp. 241–243. ISBN 978-0-7546-7418-4.

- ^ a b c d e Karl DeRouen, Jr.; Uk Heo (2007). Civil Wars of the World: Major Conflicts Since World War II. ABC-CLIO. pp. 115–117. ISBN 978-1-85109-919-1.

- ^ Arms trade in practice, Hrw.org, October 2000

- ^ "Торговля оружием и будущее Белоруссии — Владимир Сегенюк — NewsLand". newsland.com.

- ^ Yahia H. Zoubir; Haizam Amirah-Fernández (2008). North Africa: Politics, Region, and the Limits of Transformation. Routledge. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-134-08740-2.

- ^ "Statement of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the National Community abroad". UN Algeria. 16 July 2021. Archived from the original on 20 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ a b c Mannes, Aaron (2004). Profiles in Terror: The Guide to Middle East Terrorist Organizations. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7425-3525-1.

- ^ a b Cordesman, Anthony H. (2002). A Tragedy of Arms: Military and Security Developments in the Maghreb. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-275-96936-3.

- ^ a b Brosché, Johan; Höglund, Kristine (2015). "The diversity of peace and war in Africa". Armaments, Disarmament and International Security. Oxford University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-19-873781-0.

- ^ United States. Congress. House. Committee on International Relations. Subcommittee on International Terrorism and Nonproliferation (2005). Algeria's Struggle Against Terrorism. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 32. ISBN 9780160746789.

- ^ Lyubov Grigorova Mincheva; Lyubov Grigorova; Ted Robert Gurr (2013). Crime-terror Alliances and the State: Ethnonationalist and Islamist Challenges to Regional Security. Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-415-50648-9.

- ^ Kepel, Gilles (2006). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B.Tauris. pp. 263–273. ISBN 978-1-84511-257-8.

- ^ Siegel, Pascale Combelles (7 November 2008). "Coalition Attack Brings an End to the Career of al-Qaeda in Iraq's Second-in-Command". Terrorism Monitor. Vol. 6, no. 21.

- ^ Petersson, Claes (13 July 2005). "Terrorbas i Sverige". Aftonbladet (in Swedish).

- ^ Tabarani, Gabriel G. (2011). Jihad's New Heartlands: Why The West Has Failed To Contain Islamic Fundamentalism. AuthorHouse. p. 329. ISBN 978-1-4678-9180-6.

- ^ Boot, Max (2013). "Appendix". Invisible Armies.

- ^ Harmon, Stephen A. (2014). Terror and Insurgency in the Sahara-Sahel Region: Corruption, Contraband, Jihad and the Mali War of 2012–2013. Ashgate. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-4094-5475-5.

- ^ "A hostage crisis haunted by the ghosts of Algeria's bloody past". The Washington Post.

- ^ Martinez, Algerian Civil War, 1998: p.162

- ^ Martinez, Algerian Civil War, 1998: p.215

- ^ Hagelstein, Roman (2007). "Where and When does Violence Pay Off? The Algerian Civil War" (PDF). HICN. Households in Conflict Network: 24. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ Dalia Ghanem (22 October 2021). "Education in Algeria: Don't Mention the War". carnegie-mec.org. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ Eleanor Beardsley (25 April 2011). "Algeria's 'Black Decade' Still Weighs Heavily". npr.org. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ Djamila Ould Khettab (3 November 2015). "The 'Black Decade' still weighs heavily on Algeria". aljazeera.com. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ a b Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.255

- ^ Prince, Rob (16 October 2012). "Algerians Shed Few Tears for Deceased President Chadli Bendjedid". Foreign Policy in Focus. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ Cavatorta, Francesco (2008). "Alternative Lessons from the 'Algerian Scenario'". Perspectives on Terrorism. 2 (1). Archived from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.254

- ^ Whitney, Craig R. (24 May 1996). "7 French Monks Reported Killed By Islamic Militants in Algeria". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Entre menace, censure et liberté: La presse privé algérienne se bat pour survivre, 31 March 1998

- ^ a b c Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers (2001). "Global Report on Child Soldiers". child-soldiers.org. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ a b c "Explaining the Violence Pattern of the Algerian Civil War, Roman Hagelstein, Households in Conflict Network, pp. 9, 17" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ a b Ajami, Fouad (27 January 2010). "The Furrows of Algeria". New Republic. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ Hugh Roberts, The Battlefield Algeria, 1988–2002: Studies in a Broken Polity, Verso: London 2003, p. 269

- ^ Whitlock, Craig (5 October 2006). "Al-Qaeda's Far-Reaching New Partner". The Washington Post. p. A01.

- ^ Algerian group backs al-Qaeda. BBC News. 23 October 2003. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.159-60

- ^ ROBERT D. HERSHEY JR. (30 December 1989). "Worrying Anew Over Oil Imports". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- ^ a b Takeyh, Ray (Summer 2003). "Islamism in Algeria: A struggle between hope and agony". Middle East Policy. Council on Foreign Relations. 10 (2): 62–75. doi:10.1111/1475-4967.00106. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.166

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.165

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.162–63

- ^ a b Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.164

- ^ a b c Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.166–67

- ^ a b c Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.169

- ^ a b Joffe, George (2008). "Democracy and the Muslim World". In Teixeira, Nuno Severiano (ed.). The International Politics of Democratization: Comparative Perspectives. Routledge. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-134-05436-7.

- ^ Abassi Madani, quoted in Algerie Actualite, 24 December 1989,

- ^ Ali Belhadj, quoted in Horizons, 29 February 1989

- ^ see also: International Women’s Human Rights Law Clinic Archived 7 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine & Women Living Under Muslim Laws, Shadow Report on Algeria p. 15.

- ^ "algeria-interface.com". Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.171

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.170

- ^ Martinez, Algerian Civil War, 1998: p.53–81

- ^ a b Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.170–71

- ^ Interview with Slimane Zeghidour, Politique internationale, Autumn 1990, p.156

- ^ Martínez, Luis (2000) [1998]. The Algerian Civil War, 1990–1998. Columbia University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-231-11996-2.

- ^ a b Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.173

- ^ a b c Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.174

- ^ Djerejian, Edward P.; Martin, William (2008). Danger and Opportunity: An American Ambassador's Journey Through the Middle East. Simon and Schuster. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4391-1412-4.

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.258

- ^ a b c d e Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.262

- ^ a b c Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.260

- ^ Abdelhak Layada, quoted in Jeune Afrique, 27 January 1994 (quoted in Willis 1996)

- ^ Agence France-Presse, 20 November 1993 (cited by Willis 1996)

- ^ Sid Ahmed Mourad, quoted in Jeune Afrique, 27 January 1994 (quoted in Willis 1996)

- ^ a b c d e Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.263

- ^ Naughton, Philippe (20 November 1993). "Islamic militants' death threat drives foreigners from Algeria". The Times. London.(quoted in Willis 1996)

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.264

- ^ Martinez, Algerian Civil War, 1998: pp. 92–3, 179

- ^ Martinez, Algerian Civil War, 1998: p.228-9

- ^ a b c d e Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.265

- ^ "Algeria". Fields of Fire: An Atlas of Ethnic Conflict. Lulu. 2009. p. 2.07. ISBN 978-0-9554657-7-2.

- ^ Ministry of Interior and of Communications confidential communiqué, quoted in Benjamin Stora (2001). La guerre invisible. Paris: Presse de Science Po. ISBN 978-2-7246-0847-2., p. 25.

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.268

- ^ a b Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.268-9

- ^ a b Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.267

- ^ a b Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.271

- ^ (Roberts, Hugh. "Algeria's Contested Elections". Middle East Report 209. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ Nesroullah Yous; Salima Mellah (2000). Qui a tué a Bentalha?. La Découverte, Paris. ISBN 978-2-7071-3332-8.

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.272-3

- ^ El Watan, 21 January (quoted in Willis 1996)

- ^ "Algeria: A human rights crisis" (PDF). Amnesty International. 5 September 1997. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ html[dead link]

- ^ "Part 4". algeriawatch.tripod.com.

- ^ The Observer, 11 January 1998; "Algeria regime 'was behind Paris bombs'"

- ^ Manchester Guardian Weekly, 16 November 1997

- ^ Souaidia 2001.

- ^ "Quote". Archived from the original on 26 October 2005.

- ^ "Anwar N. Haddam: An Islamist Vision for Algeria". Middle East Quarterly. September 1996. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ^ Kalyvas, Stathis N. "Wanton and Senseless?: The Logic of Massacres in Algeria" Archived 12 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine Rationality and Society 1999; 11:

- ^ George Joffe Archived 12 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, "Report: Ahmad Zaoui", 3 June 2003, p. 16:See also Martinez 1998:217: "So might the GIA not be the hidden face of a military regime faced with the need to rearrange its economic resources?"

- ^ Shadow Report on Algeria To The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, Submitted by: International Women's Human Rights Law Clinic and Women Living Under Muslim Laws| January, 1999| p. 20. note 27

- ^ Kaplan 1998, p. 18.

- ^ "Political Violence And The Prospect Of Peace In Algeria", in Perihelion, journal of the European Rim Policy And Investment Council, April 2003

- ^ Calvert, John (March 2003). "The Logic of the Algerian Civil War [Review of Luis Martinez. The Algerian Civil War, 1990–1998.]". H-Net online. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.274

- ^ Profile: Algeria's Salafist group. BBC News. 14 May 2003. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ^ New chief for Algeria's Islamists, Arezki Himeur, BBC News, 7 September 2004.

- ^ Algérie: le "oui" au référendum remporte plus de 97% des voix, Le Monde, 29 September 2005 (in French)

- ^ En Algérie, dans la Mitidja, ni pardon ni oubli Archived 29 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Le Monde, 28 September 2005 (in French)

- ^ Algeria: New Amnesty Law Will Ensure Atrocities Go Unpunished, International Center for Transitional Justice, Press Release, 1 March 2006

- ^ استفادة 408 شخص من قانون المصالحة وإرهابي يسلم نفسه Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, El Khabar Archived 27 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, 25 September 2006

- ^ a b "Algeria puts strife toll at 150,000". Al Jazeera English. 23 February 2005. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ Projet de charte pour la paix et la réconciliation nationale: pas d’impunité au nom de la " réconciliation " !, International Federation of Human Rights, 22 September 2005 (in French)

- ^ "Country profile: Algeria". BBC News. 20 September 2008. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ Algeria, Encyclopedia of the Nations

- ^ a b c Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers (2004). "Child Soldiers Global Report 2004". child-soldiers.org. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.175-6

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.275

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, 2002: p.256

- ^ DAOUD, KAMEL (29 May 2015). "The Algerian Exception". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

Bibliography[edit]

- Kaplan, Roger (August 1998). ""The Libel of Moral Equivalence"". The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 282, no. 2.

- Kepel, Gilles (2002). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01090-1.

- Luis Martinez (translated by Jonathan Derrick) (1998). The Algerian Civil War 1990–1998. London: Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-85065-517-6.

- William B. Quandt (1998). Between Ballots and Bullets: Algeria's Transition from Authoritarianism. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8157-7301-6. Retrieved 23 February 2005.

- Souaidia, Habib (2001). La sale guerre [The dirty war] (in French). Paris: folio actuel. ISBN 9782070419883.

- Michael Willis (1996). The Islamist Challenge in Algeria: A Political History. New York: NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9328-2.

Further reading[edit]

- M. Al-Ahnaf; B. Botiveau; F. Fregosi (1991). L'Algerie par ses islamistes. Paris: Karthala. ISBN 978-2-86537-318-5.

- Marco Impagliazzo; Mario Giro (1997). Algeria in ostaggio. Milano: Guerini e Associati.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.