애덤 투즈의 현재의 정세를 이해하기 위한 아프간 경제에 대한 간략한 분석글이다. 정말 재밌게 읽었다. 영어가 어려운 분들은 번역기 돌려서라도 읽어보는 걸 추천한다.

여러 통계자료를 인용하며 길게 설명하지만 요점은 현재의 아프가니스탄이 세계시장 속에서 자기재생산의 조건을 획득할 수 없는, 순환형 경제구조를 만들지 못한채 현대화된 도시와 낙후된 비도시 지역으로 나눠진 이중구조적 경제 상황에 놓여 있다는 것이다. 내가 보기에는 전형적인 후진국형 사회이다.

원조를 매개로 서구사회와 연관된 지역만 비대해진 도시로 연결돼 있고 그 정점이 400만 인구의 현대화된 고층사무실과 아파트 블록으로 즐비한 저소득형 거대도시(a sprawling low-income metropolis, studded with high-rise offices and apartment blocks, with an official population of over 4 million)인 카불이다.

이보다도 더 저소득의, 적은 강수량으로 인한 식량위기마저 겪고 있는 광대한 농촌 지역은 탈레반에 끊임없이 병력을 제공해주는 저수지 역할을 하고 있다.

이 양극단 간의 괴리를 해소하기 위한 노력이 대내적으로는 농촌 개발 정책이었고, 대외적으로는 아프가니스탄을 실크로드라는 새로운 무역로의 핵심 연결고리로 포섭하는 것이었는데 둘 모두 실패하고 말았다.

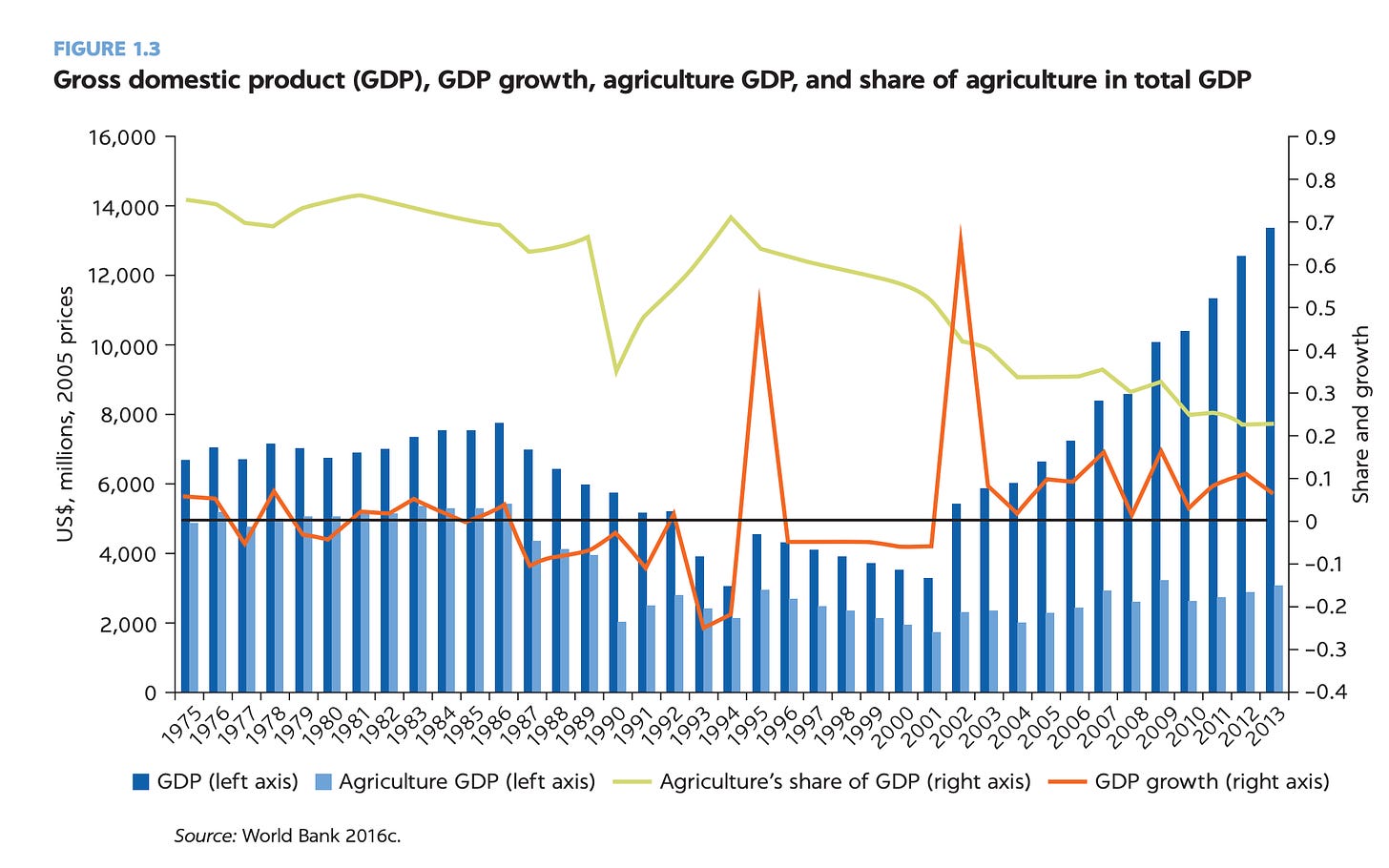

농업생산량은 거의 증가하지 않았으며 미국의 대외전략의 중심이 아시아로 이동하며 아프간이 중심축에서 빠졌으며 중국의 일대일로 또한 아프가니스탄을 우회하는 중앙아시아 경로로 나아갔다.

왜 실패했을까?

아프가니스탄은 일단 자본주의적 유통망이 작동할 수 있는, 통합적인 경제구성을 가능하게 하는 기간산업의 건설에서부터 실패했다.

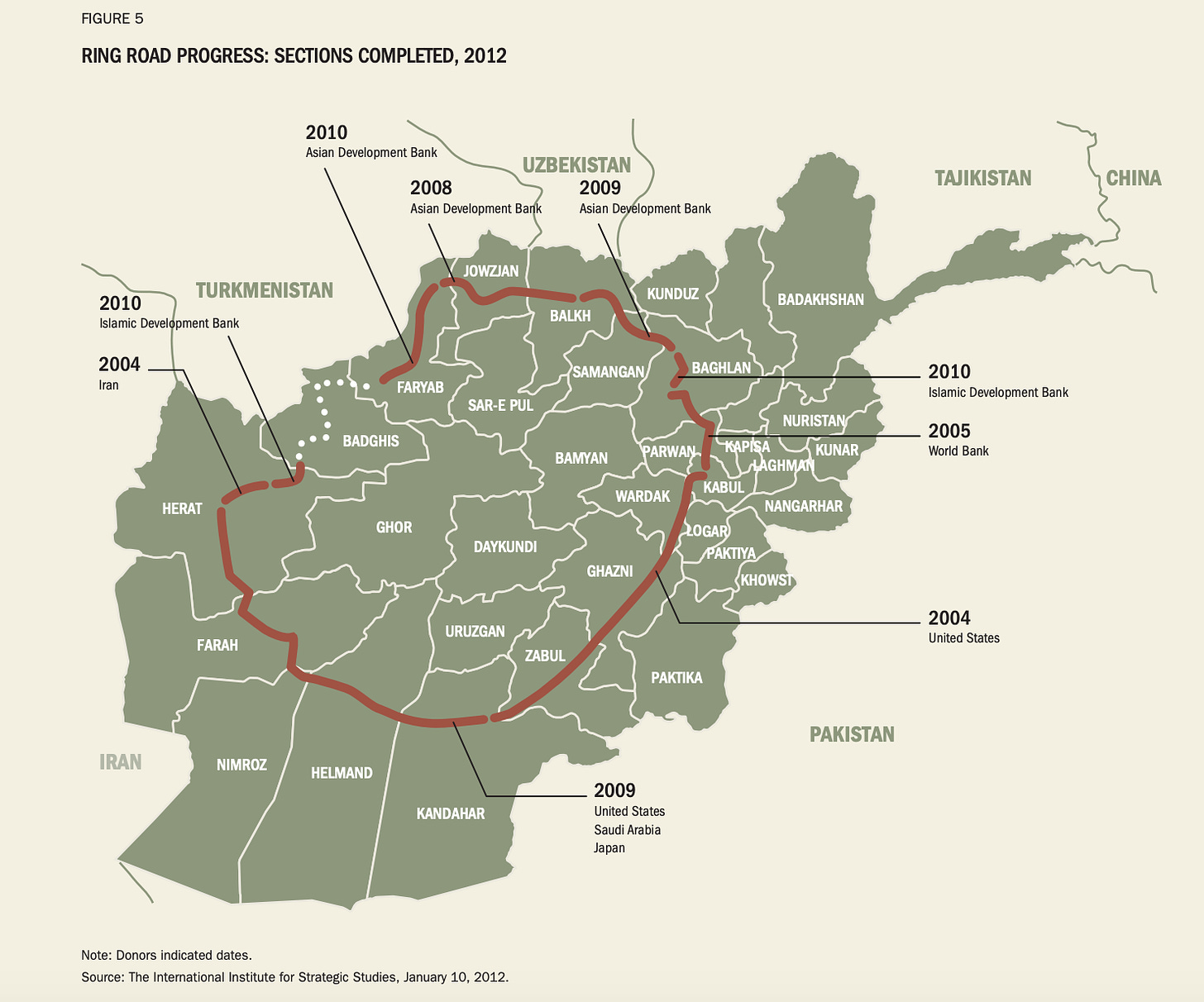

전국토에 걸쳐 상품순환을 가능하게 하는 순환도로를 완성하는 프로젝트에 엄청난 노력을 기울였지만 순환도로는 끝내 완성되지 못했다(The ring never closed).

전국토가 하나로 통합될 수 있는 여지가 없어졌다.

자본주의적 생산의 미발달로 하나의 통합성을 유지하지 못하는 상황에서 관료제의 부정부패는 국가마저도 효율적인 사회통합의 기제로 작동할 수 없다는 것을 아프간인들에게 각인시켰다.

해외로부터의 원조는 엘리트를 중심으로 분배되어 사회 말단에 이르기까지 전달되지 못했고 되려 그런 부정부패가 정부에 대한 감정적 반발을 낳았다. 원조분배의 왜곡이 사회적 불평등과 불만을 증대시키면서 체제의 불안정성을 증폭시켰다.

만약 이런 상황에서 순환형 경제구조의 건설, 그러니까 세계시장 내에서의 하나의 국민경제로 기능할 수 있는 동력을 만들어낼 수만 있었다면 상황은 개선될 여지가 있었을 것이다. 그렇지만 애덤 투즈는 현재의 아프간의 특징을 "불균등 발전과 광대한 불평등"이라 규정한다

(The defining feature of modern Afghanistan is uneven development and vast inequality).

내가 보기에 이 불균등발전과 광대한 불평등이 앞의 원조분배의 왜곡을 낳으면서 상황을 악화시켰던 것 같다. 애덤 투즈에 따르면 아프간에서의 핸드폰 보급은 대단히 급속하게 이뤄져 "핸드폰 공급자들(Cell phone providers)"이야말로 진정으로 번영한 몇 안되는 이들이라고 할 정도이다.

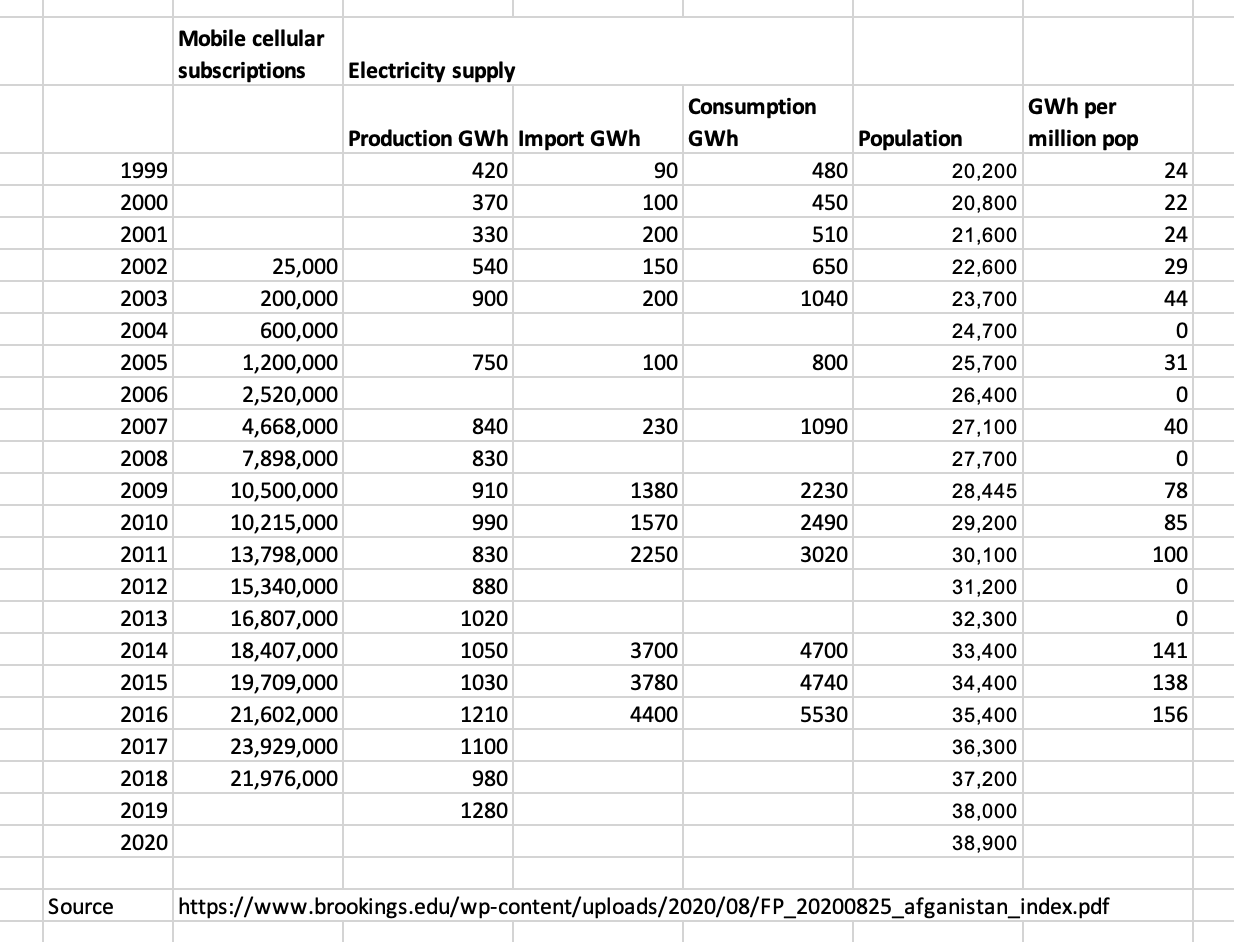

1인당 전력 소비는 핸드폰의 보급과 함께 2000년에 비해 7배나 급증했지만 그를 가능하게 할 전력 공급의 대부분, 전력 수요의 80% 이상이 사실상 해외로부터의 수입에 의존하고 있었다.

이 수입비용은 당연히 원조로 충당되었기 때문에 "현대화 된 도시 대 낙후된 농촌"이라는 구조 속에서 전자에 자원이 몰리는 원조자원의 분배상의 왜곡현상이 심화될 수밖에 없었을 것이다.

즉 세계시장 내에서 확대재생산이 불가능한 경제구조를 갖고 있는 아프가니스탄으로서는 현대화가 진행되면 될수록 무역적자가 심화될 수밖에 없기 때문에 그것을 메울 원조물자의 분배에서 현대화된 지역에 보다 많은 자원분배가 이뤄질 수밖에 없다.

한쪽에서 수명이 늘어나고, 대학교육이 확대되고, 여성인권이 개선되고, 핸드폰 등의 통신망이 확대되고, 전쟁으로 인한 사망자 비율이 줄어드는 등의 현대화 성과가 나오면 나올수록 다른 한편에서는 자원분배의 왜곡, 부정부패의 심화, 농촌의 낙후 심화, 빈곤층의 증대 등의 부정적 현상이 심화될 수밖에 없는 것이다.

이를 극복하기 위한 전국토 순환토로의 건설, 농촌개발 정책의 수립 및 새로운 무역로인 실크로드망에의 편입 등을 시도했지만 성공하지 못했다.

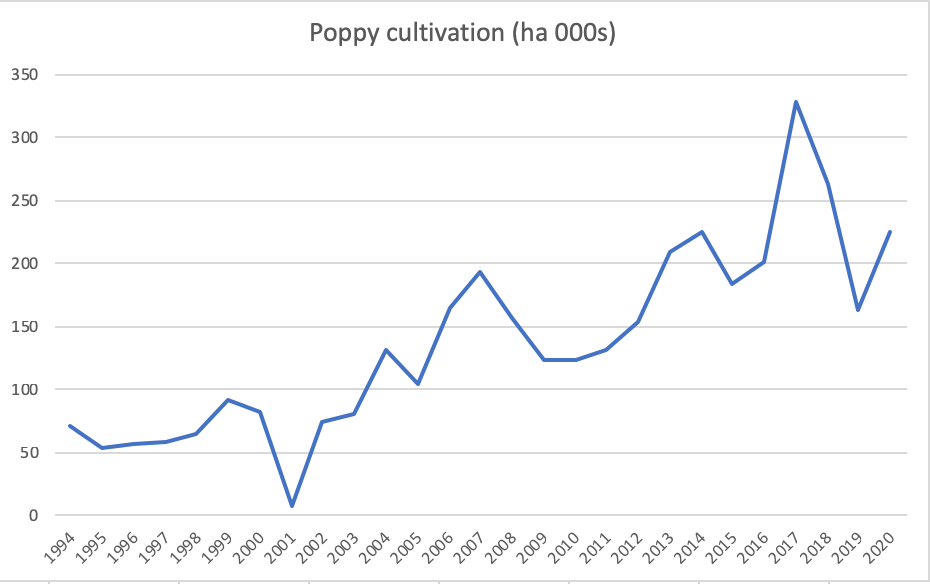

농촌의 낙후된 지역을 탈레반이 파고 들면서 아편 재배가 일상화되었고 그것에서 많은 부가 창출되었다. 기본적인 생활수단으로서의 농업생산물의 생산량은 증대되지 않았는데 아편재배는 확장되면서 약 15억 달러 규모의 소득을 농민들에게 안겨주었다.

이렇게 창출된 부는 탈레반의 주요한 자금줄이 되었고 전국토 순환도로 건설 등을 방해했을 것이다. 그렇게 광대한 면으로서의 농촌을 장악해 도시를 포위하고 결국 함락시켰다는 점에서 모택동의 중국공산당과 상당히 유사한 지점이 있지 않나 싶다. 장제스의 국민당 정부 또한 농촌 장악에 실패하는 바람에 보다 조직적이고 농민을 포섭할 수 있었던 모택동에게 끝내 천하를 빼앗겼다.

그렇지만 모택동과 탈레반이 다른 점은 탈레반은 현재 훨씬 더 현대화된, 자신들이 과거에 맡았을 때보다도 더 현대화되어 수많은 문제를 갖고 있는 국가를 안게 됐다는 것이다.

애덤 투즈는 탈레반이 친중국적인 스탠스를 취하는 것도 이런 문제점에 대한 이해가 있어서 그렇다고 보는 것 같다. 앞서 보았듯이 순환적 경제구조의 형성과 세계시장에의 편입 등을 지향하지 않고는 아프간의 문제를 해결할 수 없다면, 안정적인 지배가 불가능하다면 예단하기는 어렵겠으나 탈레반의 아프간 또한 근대화되는 방향으로 갈 수밖에 없지 않은가,

보다 효과적으로 자원을 분배하고 통합적 경제구조를 형성하는 방향이 되지 않겠는가 싶기도 하다. 미국이 탈레반에게 넘겨준 아프간은 예전의 아프간이 아니라 현대화되지 않고는 버틸 수 없는 아프간이라는 점에서 미국의 아프간 지배가 완전한 실패는 아니라는 생각이 든다. 어째.. 본글보다 더 긴 글을 쓴 것 같다..

Adam Tooze's Chartbook #29: Afghanistan's economy on the eve of the American exit.

Twenty years on.

50YoonSeok Heo and 49 others

4 comments

10 shares

===

Adam Tooze's Chartbook #29: Afghanistan's economy on the eve of the American exit.

Twenty years on.

Adam Tooze

Aug 1 16 3

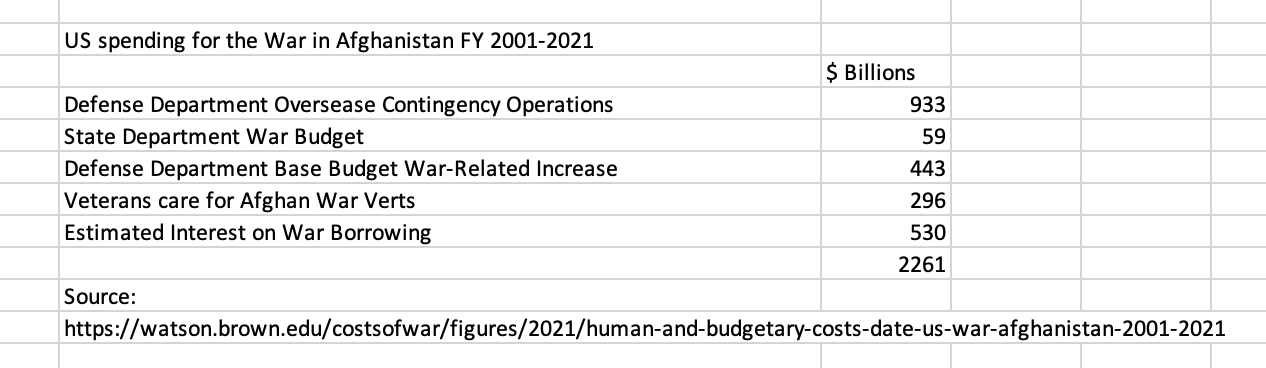

What do you do if you can see the end of your world approaching? Do you flee? Do you resign yourself? These questions were jarred into focus the other day by reports of desperate professional-class Afghans bracing for the likely return to power of the Taliban. For a large part of my adult life, the Western intervention in Afghanistan has been in the background. There was a time at Yale in the early 2010s when I was routinely teaching classes full of aid workers and veterans from Afghanistan. For a while, Stan McChrystal was a colleague. David Petraeus came for lunch. Though I had been fascinated with military history all my life, I had never been that close to a war. When you see the numbers it becomes easier to understand why the footprint of the Afghan war in American society was as large as it was. According to a widely cited shock statistics, the twenty year intervention in Afghanistan has cost the USA over $2.2 trillion dollars.

That is a staggering amount, but facing the imminent end of this twenty year engagement, I realized that I knew woefully little about the overall impact of Western intervention on Afghanistan, its economy and society. Ahead of the Western retreat, it seems that the very least one can do, is to take stock and sum up some basic facts. I only scratch the surface here. But, before I do, a personal note about Chartbook.

******

I enjoy putting Chartbook together. I hope you find it interesting. But assembling all this stuff does take quite a bit of work. So, if you appreciate the Chartbook content and can afford to chip-in, please consider signing up for one of the paying subscriptions.

Subscribe

There are three options:

The annual subscription: $50 annually

The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly - which gives you a bit more flexibility.

Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion - for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.

Paying subscribers will receive regular Chartbook Top Links emails, with some of the choice reading, viewing and listening from around the web. They will also receive invitations to exclusive book group events around the release of my new book Shutdown in September. You can pre-oder Shutdown here. Now, down to business.

********

Grasping for some perspective it makes sense to put the last twenty years of Western intervention in Afghanistan in the context of a century of contested and often violent struggle over the country's modernization. On that earlier history, Humanitarian Invasion, by Timothy Nunan is a fascinating read. The revolution of 1978 and the Soviet intervention followed by Western sponsorship of the resistance turned Afghanistan into a battlefield in the late Cold War. It was a conflict of staggering proportions.

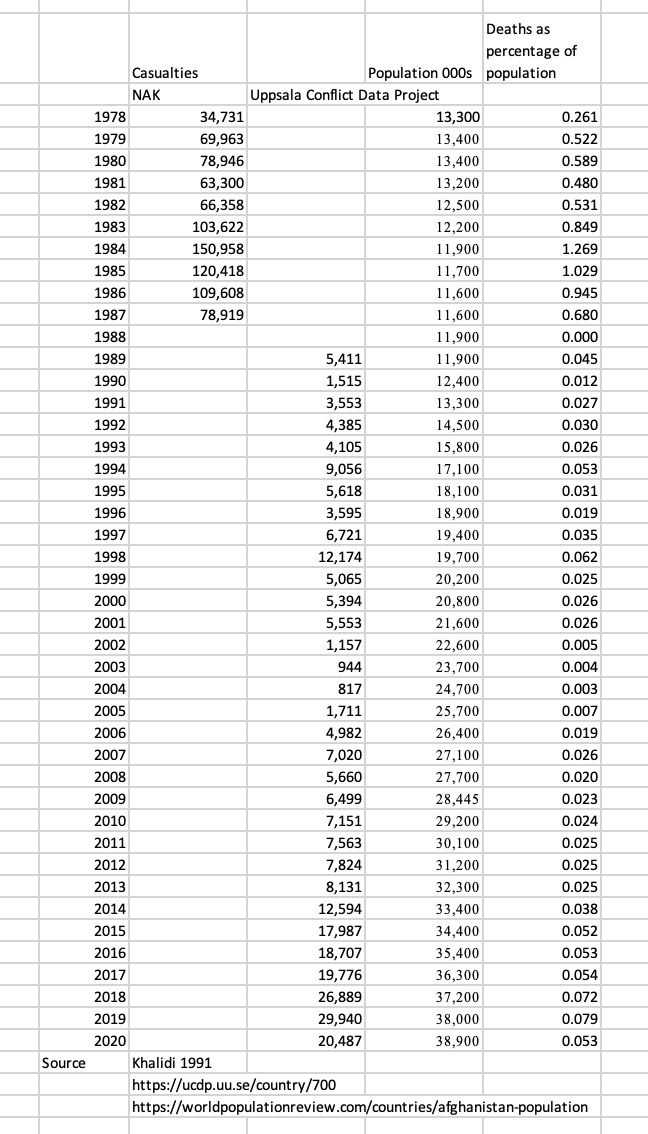

The figures from Khalidi for the Afghan-Soviet war are conservative. They cover only the period 1978-1987. They add up to a total death toll of 870,000. There are not unreasonable estimates that put overall mortality at twice that level. The scale of this violence in the 1980s dwarfs anything that followed. In 2019, 0.078 of the Afghan population were killed in clashes between government and Taliban forces. In 1984, a staggering 1.35 percent of the Afghan population fell victim to the war in a single year. In relation to population that is 19 times worse than the current casualty rate.

I do not cite these figures to excuse or relativize the violence that has followed. More people were killed in Afghanistan in 2019 than at any time since the end of the Afghan-Soviet war. More than during the conquest of the country by the Taliban during the late 1990s. But, the scale of the 1980s cataclysm is staggering. The losses, at between 7 and 10 percent of total prewar population, are in the ball park of those suffered in Eastern Europe and the Balkans in World War II. Only very big wars with large civilian casualties have significant demographic impact. In the 1980s, Afghanistan’s population stopped growing.

By comparison, the warlord and Taliban periods of the 1990s were relatively less lethal. That does not mean that they were good times. Not for Kabul, which in the 1990s was sucked into the fighting for the first time. Not for those Afghan women who had participated in the emancipatory politics and culture of the cities and found themselves living under the misogynistic regime of the Taliban.

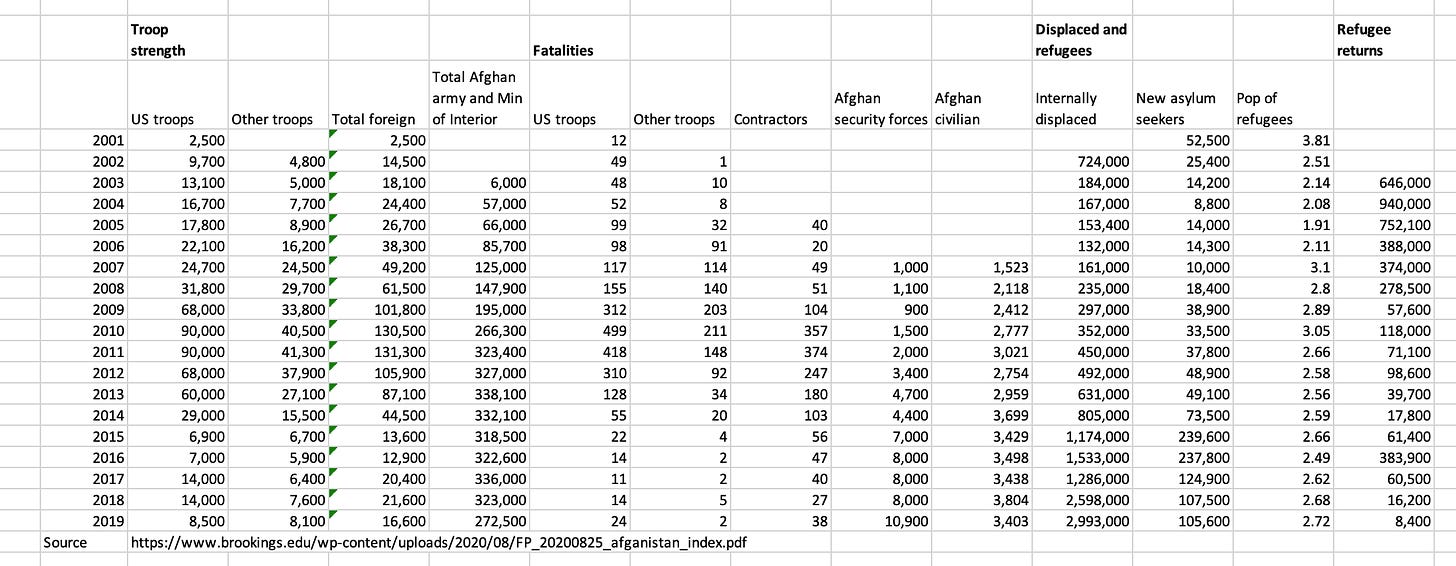

Going by the mortality data, the Western intervention in Afghanistan after 2001 at first continued the downward arc of violence. Measured in terms of the death toll, 2003 and 2004 were the most peaceful years that Afghanistan has enjoyed since the 1970s. But from 2006 the intensity of Taliban resistance surged and the Western alliance responded. Between 2009 and 2013, the US and its allies mounted something akin to a full-scale occupation. In 2011 the combined strength of the US, allied and Afghan forces deployed against the Taliban insurgency peaked at over 450,000.

The casualties were never on a scale to compare with the Afghan-Soviet war. A better measure of the disruption is the internal displacement of population, which surged along with the scale of troops deployed. Beginning in 2014 there was a wave of asylum seeking abroad, which, in 2015 in Europe, merged with the “Syrian” refugee crisis.Then, as the draw down of Western military forces began in earnest and the Taliban mobilized, the scale of the fighting widened dramatically. The Afghan security forces began to take very serious casualties and internal displacement surged alarmingly.

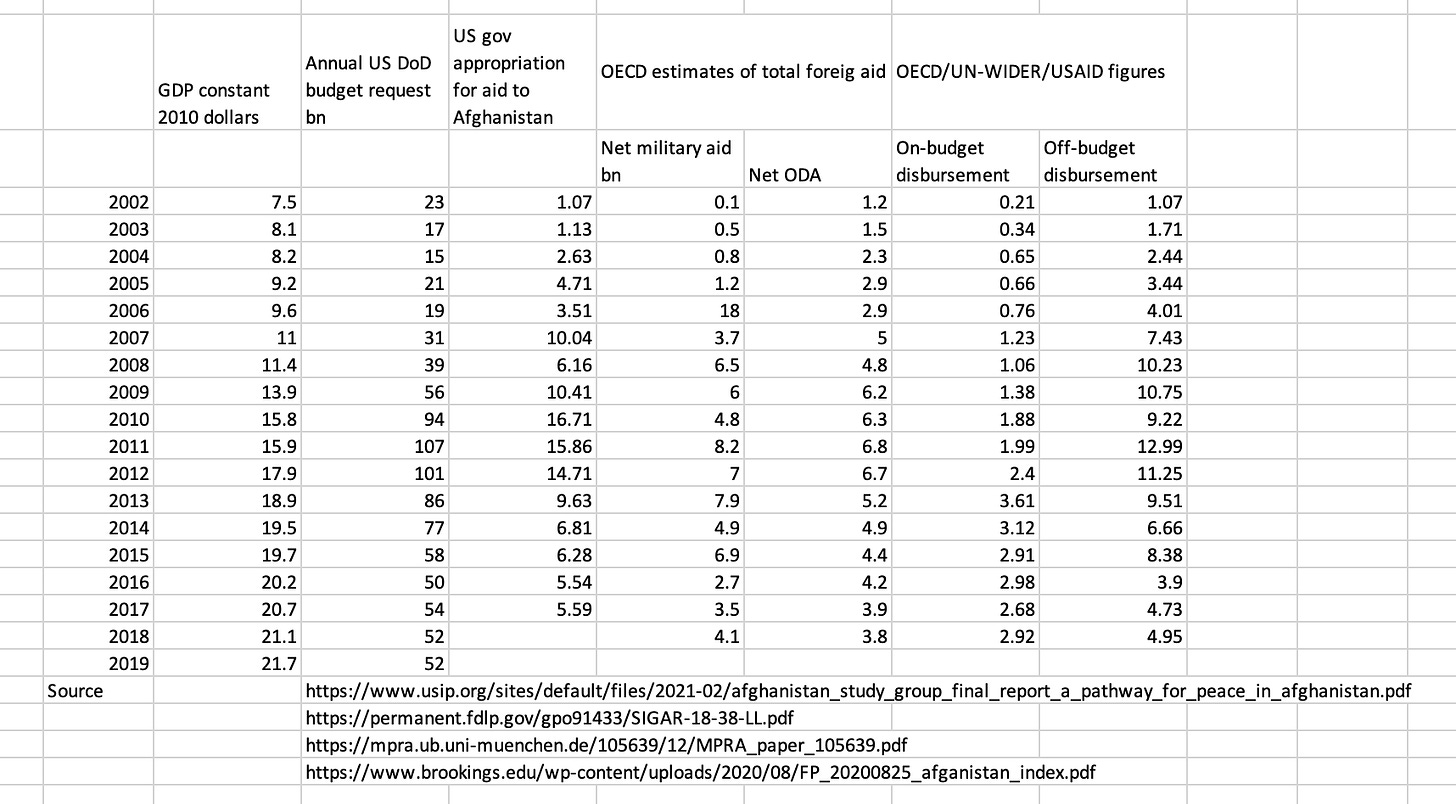

Seen from high altitude, the pattern of economic development in Afghanistan over the last twenty years follows a similar path. At first, Western aid was surprisingly small-scale and modest in conception. It built to a sudden crescendo in the early 2010s at the time of the US surge and has ebbed since.

Given Afghanistan’s huge development challenges, one might think that economic development would have top priority. In fact, the ratio of military to civilian development spending was in the order of ten to one. But, the scale of Western involvement is staggering, nevertheless. In many years Western aid spending exceeded the measured size of Afghan GDP. The figures have a surreal, Alice in Wonderland quality. How could you fit so much aid money into such a small economy? Where did the money go?

One obvious answer is that tens of billions were swallowed up by corruption and the grey economy. Wealthy Afghans became large property owners in the Gulf states. So crass are these divides that they call into question the very notion of an Afghan national economy as we normally understand it. All statistics are constructs. GDP is a particularly elaborate construction. And in the case of Afghanistan it obscures the fact that a national economy as we conventionally understand it, barely exists. On the ground there are “economies” of urban merchants and handicrafts and communities of hard scrabble farmers, but they did not constitute the kind of integrated circular flow as which we imagine a modern economy. Achieving a circular flow was actually a strategic issue in Afghanistan. A huge amount of effort went into the project of completing the ring road that notionally enables the circulation of goods and people around Afghanistan. The ring never closed.

Source: SIGAR

Afghanistan’s most valuable crop is illegal opium. It does its best to show up nowhere in anyone’s accounts. But there can be little doubt that since the early 2000s, cultivation has progressively increased.

Source: UNODC

At farm-gate prices, in 2017 opium generated about $ 1.5 billion in income for Afghan peasants. The fortunes of the countryside fluctuate with heroine prices in the West.

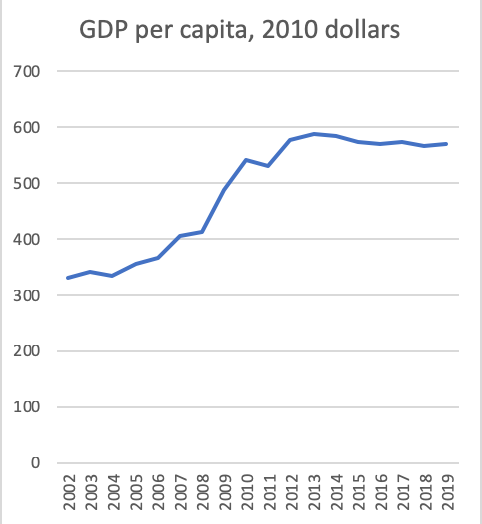

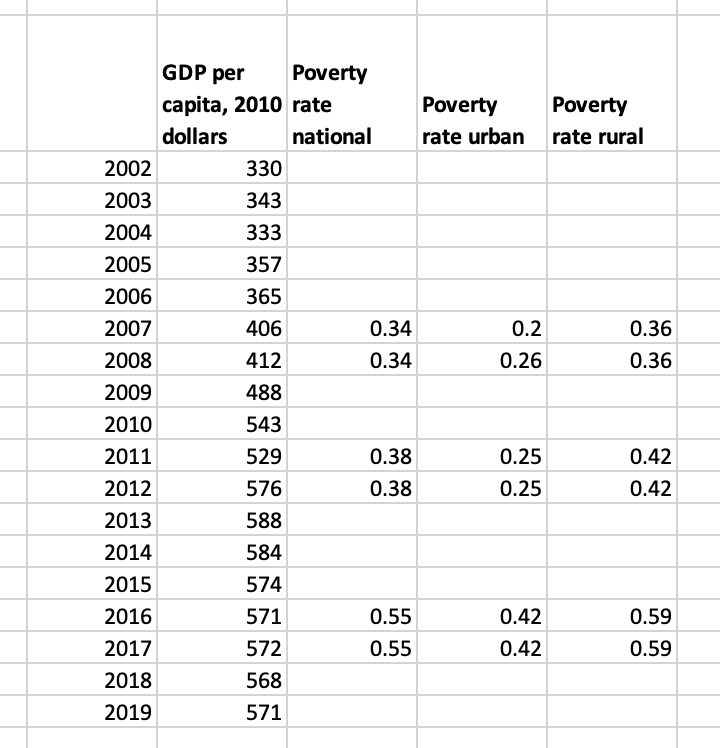

For what they are worth, data for Afghanistan’s GDP per capita show a surge between 2000 and 2014. GDP per capita was driven upwards by injections of foreign spending and the restoration of ordinary farming and commerce, as security was restored. Since 2014, as aid dwindled and violence returns, GDP has stagnated. With a rapidly growing population, that means that GDP per capita is shrinking.

Source: Afghanistan Index

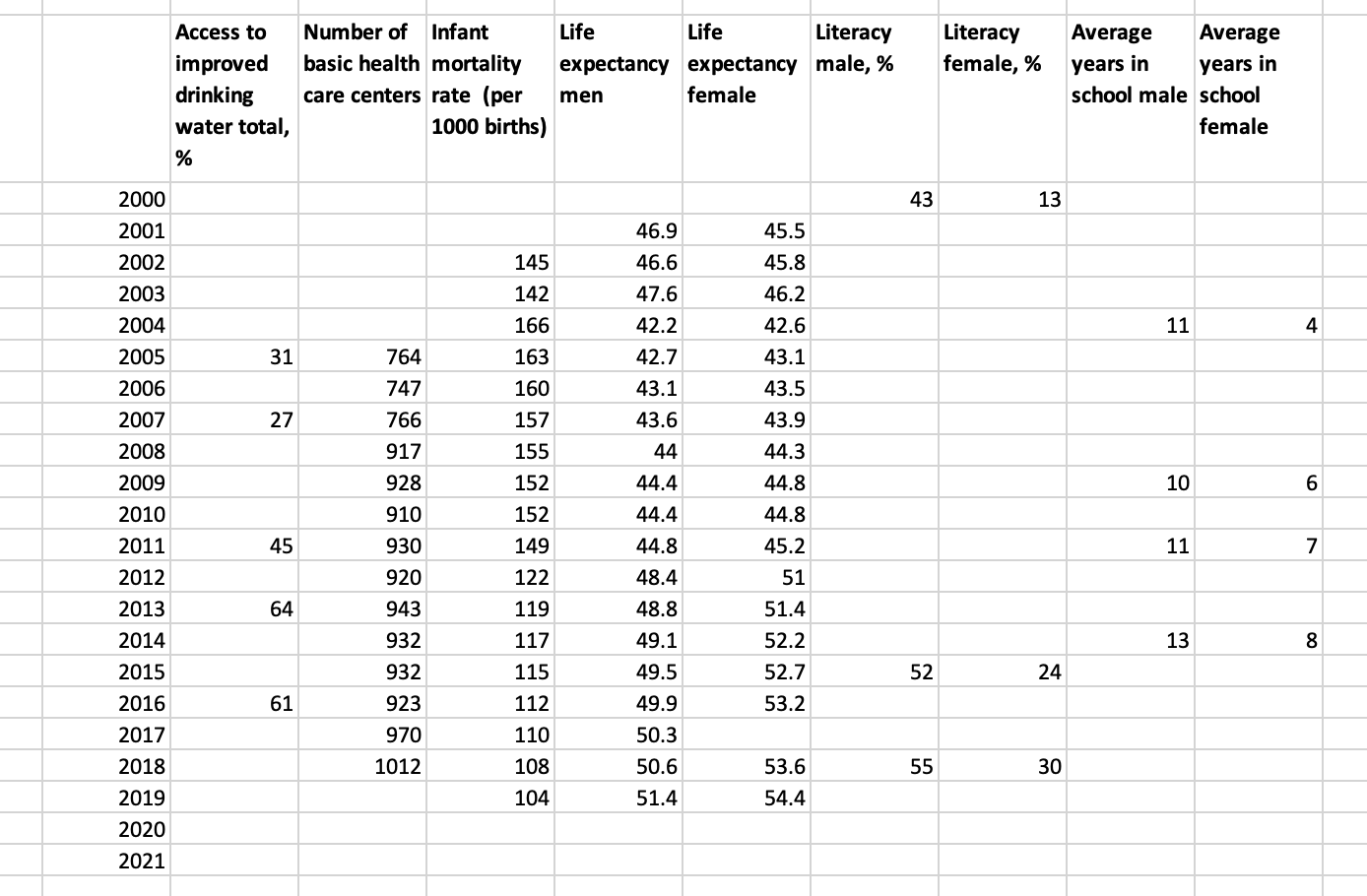

These data are clearly hedged by uncertainty. But other markers of modernization track the same curve.

Source: Afghanistan Index

Life expectancy has increased. This is driven by a rapid fall in infant mortality and striking life expectancy gains for women, presumably, through much better maternal care. Whereas in 2000 Afghan men lived longer than women, now Afghanistan has the more normal pattern of women outliving their menfolk.

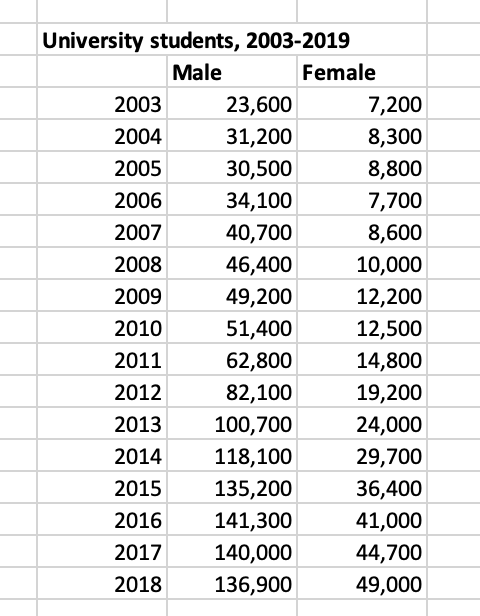

From 30,000 in 2003, the number of students enrolled in Universities in Afghanistan has risen to more than 180,000. In 2018, there were 49,000 female students.

Source: Afghanistan Index

Like everyone else, Afghans are addicted to their cell phones. There are enough cell phone subscriptions for more than half the population. Cell phone providers are one of the few parts of Afghanistan’s modern economy that have truly flourished. To run phones, people need power. Electricity consumption per capita has gone up approximately seven times since the 2000. To feed that growing demand, Afghanistan has expanded its own generating capacity. But, increasingly, Afghanistan has come to rely on power imports - from Uzbekistan, Iran and Turkmenistan - which account for almost 80 percent of its power needs. The inflow of aid covers Afghanistan’s yawning trade deficit.

Source: Afghanistan Index

But for all the recorded signs of economic growth and modernization, there has been no success in poverty eradication. In fact, as per capita income increased, so did the rate of poverty. And in recent years, as growth has ground to a halt, the poverty rate has surged. Today, over half of Afghanistan’s population are officially counted as poor.

Source: Afghanistan Index

The defining feature of modern Afghanistan is uneven development and vast inequality. The six major cities Kabul, Mazar, Jalalabad, Herat, and Kandahar are a world apart from the other 28 provinces. Critics of the aid regime like Kate Clark refer to Afghanistan as a rentier state. Western aid funneled into a hierarchical and balkanized social and political system has given rise to a parallel economies. Elites have monopolized growth for themselves. Meanwhile, those at the bottom are left behind. The Taliban are sustained by resilient organization, by commitment and by an underground economy of considerable scope. But what ultimately keeps their movement alive is the misery of the Afghan countryside and the rage against pervasive corruption and injustice felt by so many young men.

The Afghan political class and their outside backers have, periodically, shown an awareness of this basic connection. Ashraf Ghani, currently Afghanistan’s President, is a cultural anthropologist who earned his PhD from Columbia in the early 1980s with a thesis entitled, ‘Production and domination: Afghanistan, 1747-1901’. After taking several positions in US academia, he moved to the World Bank 1991 as lead anthropologist. Unsurprisingly, given this background, when he was Finance Minister under Karzai in the early 2000s, Ghani pushed a full suite of rural development programs. As they intensified their engagement with Afghanistan after 2006 the Americans became more and more focused on stabilization and development. Rural development programs were the essential complement to counterinsurgency operations. At their most grandiose America’s plans envisioned Afghanistan as a key staging post in a “New Silk Road”. General Dave Petraeus and a “tiger team” at the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) envisioned Afghanistan as a key link in a new transcontinental trade route. Trade and economic growth would fill the gap left when America’s troop surge wound down. On 20 July 2011 Secretary of State Hillary Clinton embraced the CENTCOM New Silk Road initiative in a speech she gave in Chennai, India. But the idea never took off. A few months after her Chennai speech, Clinton announced the Obama administration’s pivot to Asia, which was widely seen as a turn away from Afghanistan towards wider horizons. It would be China that took up the New Silk Road vision, with One Belt One Road in 2013. But, China’s BRI bypasses Afghanistan, leaving it to the Americans.

Meanwhile, on the ground, the data told a depressing story of rural retardation. Whilst the rest of the Afghan economy grew rapidly between 2001 and 2013, agricultural output barely increased.

Source: World Bank

The failure of development not only makes the countryside a recruiting ground for the Taliban. It also increases vulnerability to natural shocks. In 2018 Afghanistan was wracked by drought. The rains returned in 2019. But in 2021, in the North and the West of the country, 2-3 million people who rely on rain-fed agriculture and natural pasturage are again facing disaster. As the US prepares its exit, the Norwegian Refugee Council is warning that “More than 12 million Afghans – one-third of the population – now face 'crisis' or 'emergency' levels of food insecurity.”

With Afghanistan in crisis, the Taliban seem poised to sweep back to power. Once again they are exploiting a mood of crisis. But in the 1990s they took charge of a country eviscerated by the war with the Soviet Union. Afghanistan today is still poor, but it is not in the condition it was twenty five years ago. Kabul in the 1990s was a ruined city with a population of barely over a million. Today, it is a sprawling low-income metropolis, studded with high-rise offices and apartment blocks, with an official population of over 4 million. What kind of regime could be established by the Taliban over such a city? What kind of future can they deliver for Afghanistan and for their constituency in the countryside? Little wonder that the Taliban have been assiduously courting Beijing. Afghanistan needs all the friends it can get.

William FarrarAug 8

The only thing that I can think of is that the 2.2 Trillion dollars and American blood, bought a 20 year reprieve for hundreds of thousands, if not a million, women and children would have suffered under the Taliban, and have grown up ignorant and uneducated except for salafist Islamic indoctrination.

I worry for them,now that we have left, and am wondering just how all of those translators and other Afghani's can be taken out with Bagram in control of the Taliban.

The real question is what is more important, tax payer money or the lives of people.

The fact that the question is raised is the answer.

Everything is evaluated as worthy or unworthy in relationship to money.

Even a cost benefit analysis breaks down to profit or loss.

Quality of life, human lives, democracy, erecting a bulwark against terrorism and aggression are not factored into the analysis, except for how much it costs.

Reply

myceliumAug 1

IxJac is a man who has for the past fifteen years while posting on the below forum claimed to have been a Canadian Forces soldier who deployed to Afghanistan twice in a rear-area capacity (intelligence staff for Canadian forces in Kandahar). While it is difficult to be sure of anything on the internet, his extremely long history of posts and his numerous interactions with other claimed soldiers (and the sheer quality of his analysis) have given him substantial credibility. His commentary on the ongoing collapse of the Afghan government is illuminating.

https://forums.spacebattles.com/threads/best-afghanistan-withdrawal-and-outcome-what-should-the-plan-be-and-what-leverage-does-the-coalition-have.918450/#post-74084499

Reply

1 more comments…

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.