--

https://thediplomat.com/2016/06/lost-and-found-in-uzbekistan-the-korean-story-part-1/?fbclid=IwAR0Syv75kxSzmbx2LTQem7eWG5qjG0jLjHojZCfUYIcuTTJrPgwziwkB5jg

--

https://thediplomat.com/2016/06/lost-and-found-in-uzbekistan-the-korean-story-part-2/?fbclid=IwAR0Syv75kxSzmbx2LTQem7eWG5qjG0jLjHojZCfUYIcuTTJrPgwziwkB5jg

https://thediplomat.com/2016/06/lost-and-found-in-uzbekistan-the-korean-story-part-2/?fbclid=IwAR0Syv75kxSzmbx2LTQem7eWG5qjG0jLjHojZCfUYIcuTTJrPgwziwkB5jg

--

https://thediplomat.com/2016/06/lost-and-found-in-uzbekistan-the-korean-story-part-3/?fbclid=IwAR0Syv75kxSzmbx2LTQem7eWG5qjG0jLjHojZCfUYIcuTTJrPgwziwkB5jg

--

Lost and Found in Uzbekistan: The Korean Story, Part 1

Victoria Kim, in looking into her own history, dives into the story of how Koreans came to Uzbekistan.

By Victoria Kim

June 08, 2016

Korean, Russian, Tatar, Ukrainian and Uzbek kids all together in a class photo (Tashkent in the early 1940s)Credit: Courtesy of Victoria KimADVERTISEMENT

This is the first in a three-part presentation of Victoria Kim’s multimedia report, created in memory of her Korean grandfather Kim Da Gir (1930-2007), which details the history and personal narratives of ethnic Koreans in Uzbekistan. It was originally published in November 2015 and is republished here with kind permission. Make sure to read part two and part three.

***

“The personal story of my family is at the same time the story of suffering of all Korean people… I want to tell this story to the world, so that nothing like that ever happens again in our future.”

— Nikolay Ten

***

My mom, a half-Korean child among multi-ethnic kids from all over Soviet Union in a Tashkent kindergarten in the early 1960s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Introduction

Strolling along the streets of Tashkent or riding in a small marshrutka minibus – a common mode of transportation in this busy and bustling Central Asian city with a population of about 3 million people – you would feel no surprise looking at the multitude of different faces.

Tanned and dark haired or white skinned and blond, with blue, green, or brown eyes, Russians, Tatars, or Koreans would always appear in the crowd of local Uzbeks. There used to be even more of them here several decades ago, living together in this calm and friendly city full of sunshine and welcoming shade.

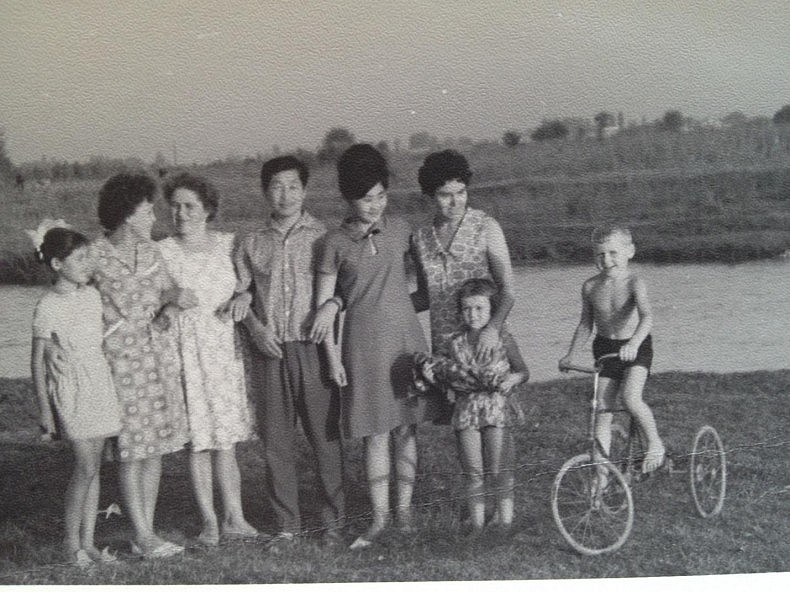

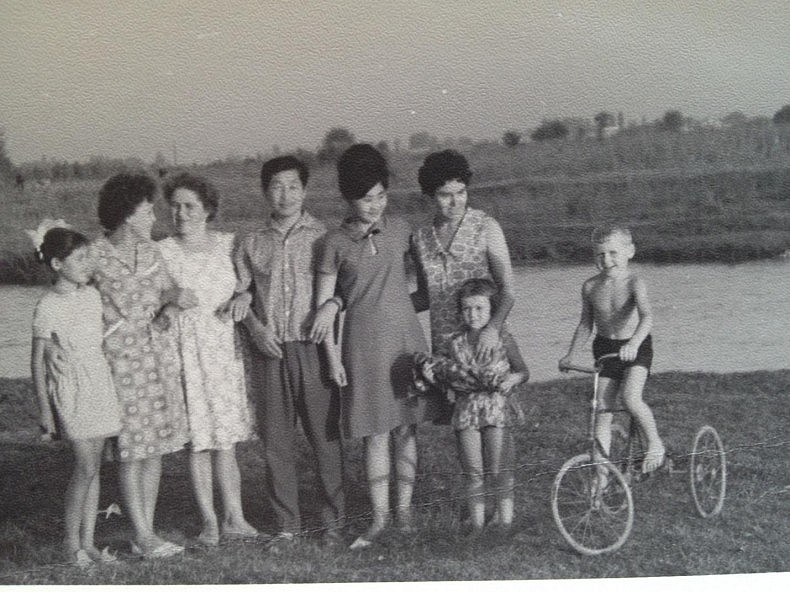

A true friendship of people in Tashkent in the late 1960s: Russians, Tartars. and Koreans together, having a rest near the Karasu river. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

By now, many people have left together with their untold stories about this capital of “sun and bread,” a Soviet-day Babylon that became a true Noah’s ark hosting and hiding the survivors of a horrifying storm of ethnic repressions.

Here, lost deep in the heart of a Central Asian desert, they multiplied, prospered and lived in peace. Russians, Jews, Germans, Armenians, Meskhetian Turks, Chechens, Crimean Tatars, and Greeks — most of them had found a second home here, temporary if not permanent.

After the Soviet Union’s breakup in 1991, many ethnic groups abandoned this newly rising and predominantly Muslim country. Some feared possible persecution — which fortunately never happened — while others simply followed their own practical reasons and departed.

Some left earlier, as soon as the restrictions on their movement were lifted in the wave of so called “democratization” early in the 1970s.

However, there was one particular community of people that chose to stay in Uzbekistan. They actually had nowhere else to go. Through the years of pain and suffering, hard physical labor, adaptation, and assimilation, this country had become their one and only true home.

These people are Uzbek Koreans, and this story is about them.

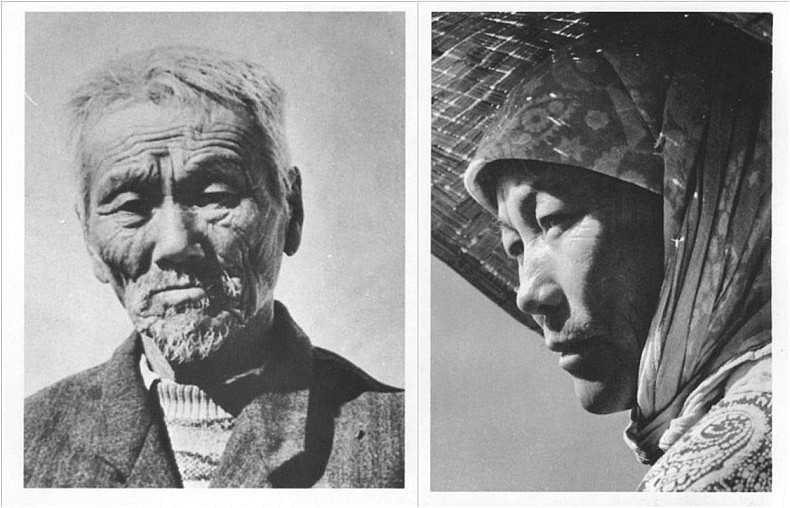

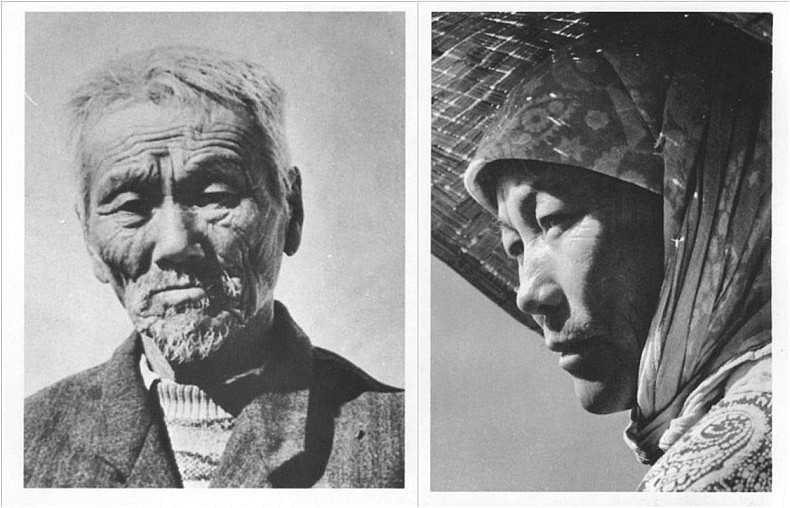

Left: Park Ken Dyo, the creator of kendyo type of rice that rose him to prominence in Soviet Uzbekistan.

Right: A Korean farmer in Soviet Uzbekistan. Courtesy of Victoria Kim

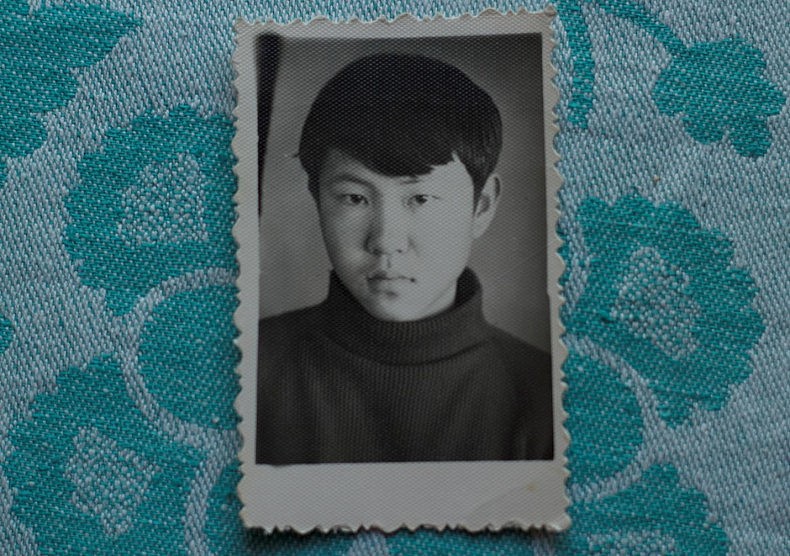

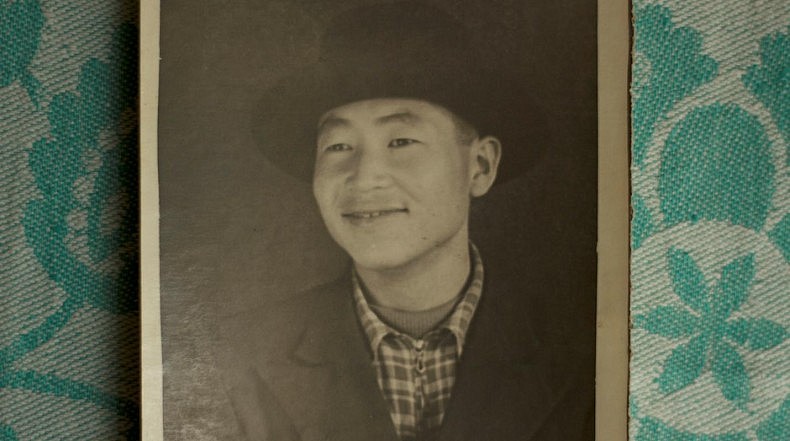

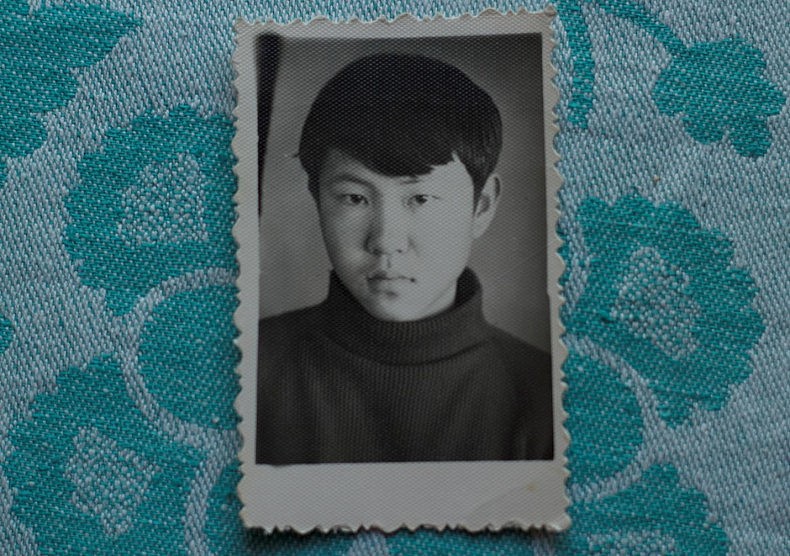

Young Nikolay Ten. Courtesy of Victoria Kim

Nikolay Ten

Nikolay and I were simply bound to meet. When I first saw him on the calm and quiet streets of Tashkent in the early spring of 2014, he was selling souvenirs, antiques, and traditional Uzbek clay figurines to passersby and tourists in the central city square formerly known as Broadway.

Passersby and tourists looking for traditional Uzbek souvenirs on Broadway in Tashkent. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

The several theaters it used to host were long gone, as were the crowds. The name has somehow stuck, adding nostalgia and curious mystery to this huge and otherwise deserted area full of flowerbeds and monuments to fallen heroes.

Only a handful of artists, painters and antiquity collectors remained here, including Nikolay, a small and aging Korean man who would pass anywhere for a “typical” Central Asian. He looked more like a Kyrgyz, Kazakh, or Mongol, with his bald head and dark skin tanned by the sun.

Nikolay on the day I met him on Broadway in Tashkent in the early spring 2014. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Something very special on his smooth and round face was his smile – the kind, honest, and hesitant smile of a thoughtful child that he still kept somewhere deep in his heart.

I bounced into Nikolay in the middle of my own personal quest. I was looking for a story almost disappeared and now hidden somewhere near. The ghosts of our recent past were haunting me from all sides on that warm and cloudy spring day on Broadway, and probably, they brought me to Nikolay and made him reveal his story to me.

Uzbek Koreans in the late 1940s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

At the same time, the urge to keep telling this story is somehow very understandable for both of us. These are our collective memories, imprinted in the genes of all Uzbek Koreans.

They are still kept in the taste of pigodi, chartagi, khe, or kuksi – a handful of salty and spicy North Korean dishes that have become a representative part of our vibrant and mixed Uzbek cuisine.

Local Korean sellers at a typical Korean salad stand in Tashkent. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

They still resonate in the sound of a few remaining words in the Hamgyong dialect, which Soviet Koreans originally spoke when they first arrived to Uzbekistan in 1937. They still mark our ancient lunar calendar during the traditional holidays, such as Hansik and Chusok – spring and autumn equinoxes – or tol and hwangab, the auspicious first and sixtieth birthday celebrations.

These ancient and typically Korean festivities and cultural rituals have somehow survived all former official prohibitions and are vigorously observed across Uzbekistan by one unique ethnic group.

This very tight community also shares a deeply secretive history known through the tragic accounts of past persecutions, repressions, and deaths. These stories would only be told to close relatives and passed among family members, from one generation to another.

The sufferings those stories unveil are always very deep. Equally deep is the pain the memories still provoke.

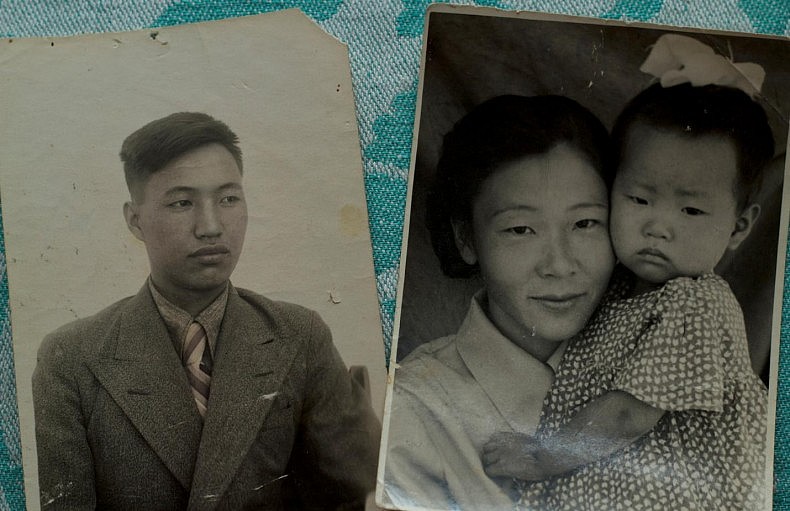

My then-young grandfather Kim Da Gir. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

My Grandfather

I also have a story woven into the secrets of this tragic past. A long time ago, my grandfather told it to me only once and never wanted to speak about it again.

This is the story of a little boy who traveled one cold winter with many other people, all stuck together inside a dark and stinking cattle train. He traveled on that train together with his parents and siblings for many weeks, until one day they arrived to a strange place in the middle of nowhere.

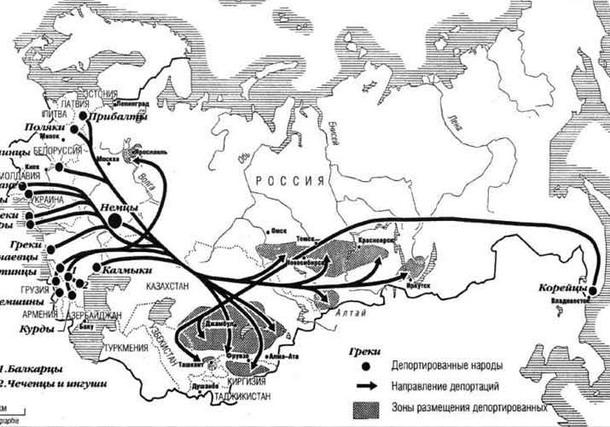

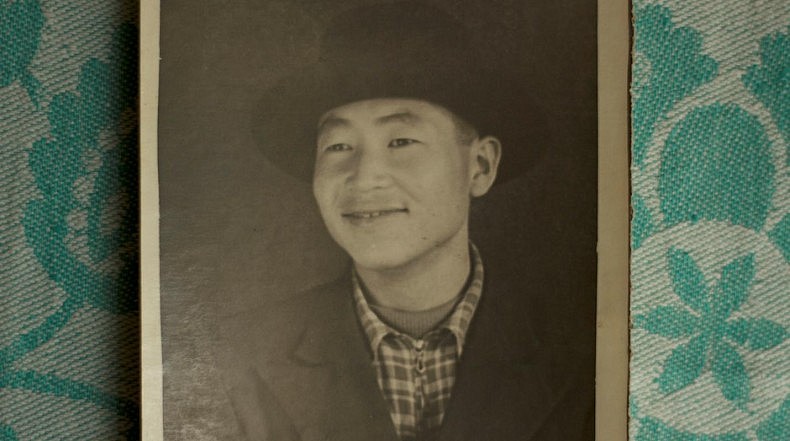

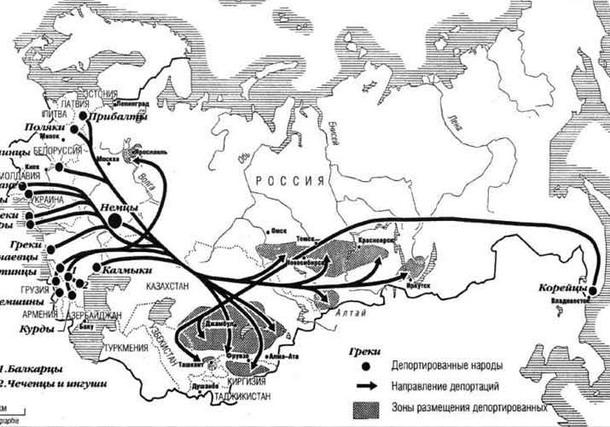

A map showing the forced relocation of “unwanted” ethnic minorities in the Soviet Union throughout the late 1930s – early 1940s. Koreans were the first entire nationality to get deported in 1937 from the Soviet Far East to Central Asia. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

That place was somewhere in Soviet Uzbekistan. It was 1937, and my grandfather was only seven years old.

What brought him to empty and deserted Central Asia was the first Soviet deportation of an entire nationality. What united all of them as the victims of this massive deportation was their ethnicity. They all happened to be Koreans.

The cattle train story was the only thing my grandfather ever told me about those painful and complicated times. Yet all his untold stories would keep haunting me later on, as would his very apparent Korean appearance and our Korean last name.

In order to affirm my partly Korean belonging I eventually studied Korean, or rather its classical Seoul dialect, which my grandfather was never be able to understand.

Studying Korean together with my Korean classmates in Tashkent in the early 2000s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

I would keep looking for any affinity with Korea and even graduated in the Korean studies at a renowned university in the United States, which my grandfather happily lived to know.

So far from my actual Korean roots and never at peace with this understanding, I would keep looking for those unique Korean stories forgotten and lost deep in Central Asian sands. It would become my personal quest to uncover the secret spaces left blank on purpose, in our family history and in the history of all Uzbek Koreans.

Uzbek Korean heroes of socialist labor in the late 1940s – early 1950s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

My grandfather lived a relatively successful life in Uzbekistan. He went to study in Moscow and was later sent to work in rural Ukraine, where he met his future Russian wife, a woman who was working in the same town. They returned to Tashkent together in 1957, already married and with my one-year-old mother.

For most of his life, my grandfather worked as a chief engineer in the construction bureau at a major industrial plant in Tashkent. He developed and patented a lot of technical innovations for cotton picking machinery – we still keep all his certificates of achievement at home.

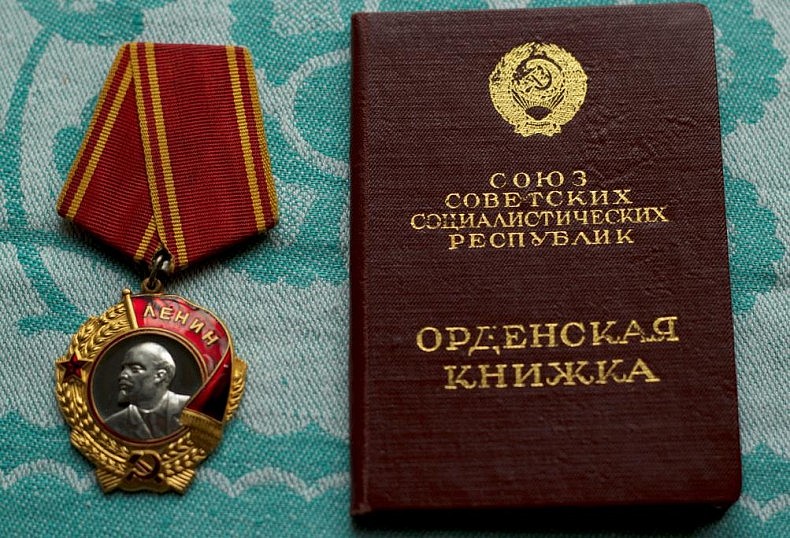

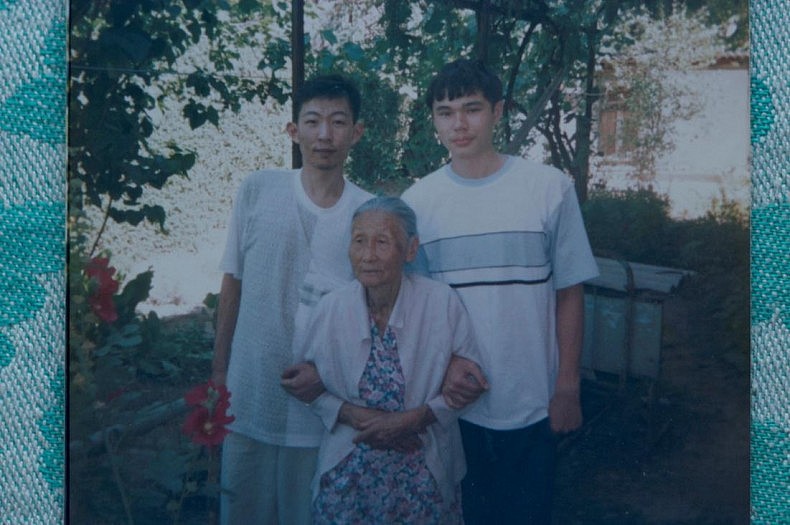

This is how the Korean community is ingrained in our social fabric – as extremely hard working people and quite a prosperous diaspora. In fact, many Koreans – including Nikolay’s mother and my grandfather – have been awarded with numerous state medals for their very hard labor during the Soviet times.

Uzbek Koreans are also known for their indisputable role in the development of Uzbekistan’s national agriculture. Traditional peasants, they passed to Uzbek locals their generations-worth of farming knowledge and techniques. Even now, the best types of rice grown in Uzbekistan and used in the preparation of most representative Uzbek dishes are still lovingly called “Korean.”

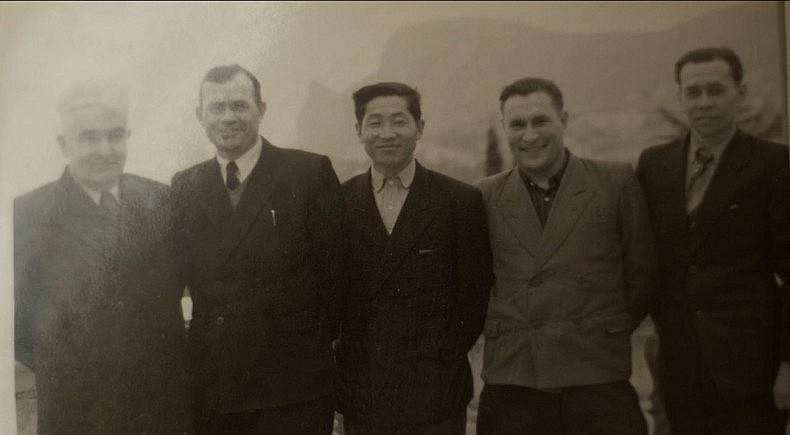

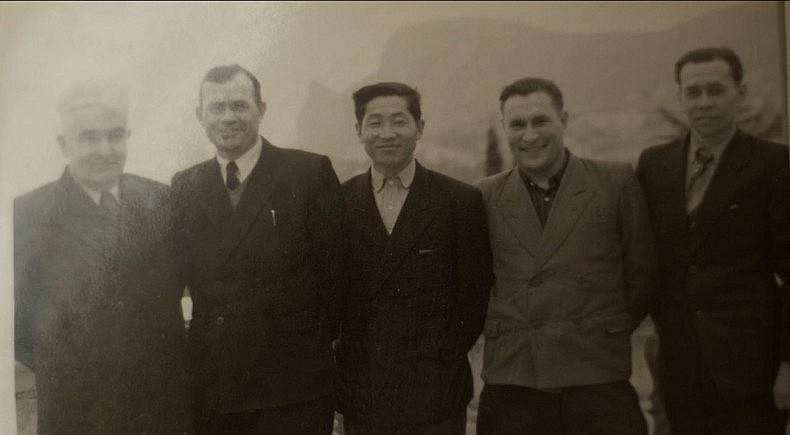

My grandfather (in the center) with his colleagues from the construction bureau. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

However, little is known about the heavy toll Uzbek Koreans had to pay in order to gain such a high reputation in our society. They were forced to come to Uzbekistan, they had to develop it and turn into their own, they bore children upon it and – very slowly – it became their one and only home.

Nikolay and I are desperate to preserve our history – in the name of all Korean people. This is the story of three generations of his family. It is also my grandfather’s story. Nikolay and I are determined to keep it alive, so the history may never repeat itself.

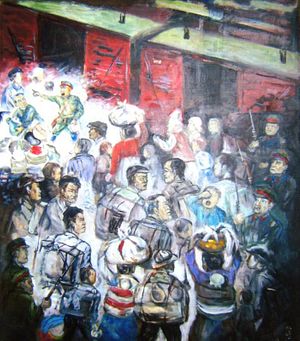

Soviet Koreans while being deported from the Far East to Central Asia in 1937. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

At least, we truly hope so.

Before 1937

Nikolay’s mother was born in 1919 in Maritime province (Primorsky Krai), in the village called Crabs. Back then it belonged to Posyet national district, and the whole territory of this province was an official part of the Soviet Far East.

In fact, this tiny piece of land – stuck between northeastern China and the upper tip of present-day North Korea on one side, and surrounded with the Japanese Sea on the other – used to serve as a buffer zone for the Soviets throughout most of the 1920s.

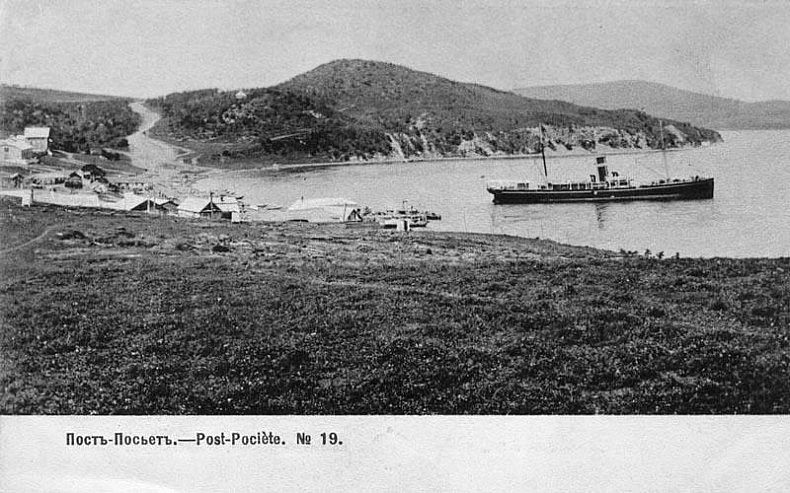

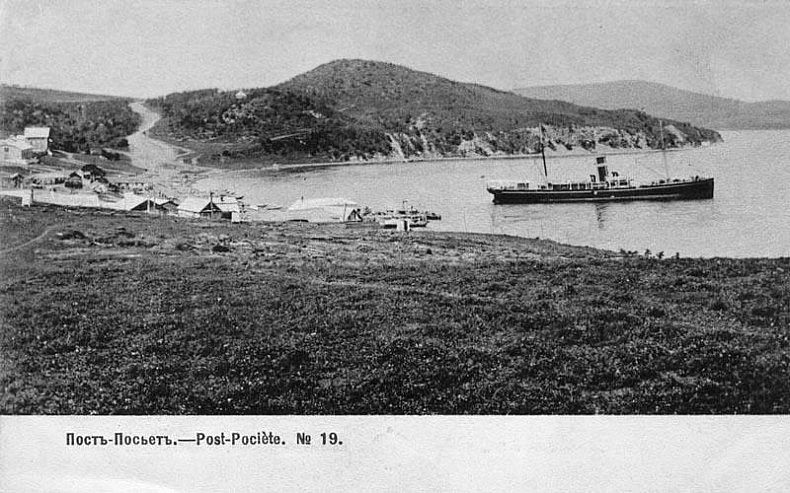

Posyet in the early 1900s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Koreans originally started moving here in the late 19th century, escaping harsh living conditions, poverty and starvation in the north of the Korean peninsula. They built the first Korean villages and towns in the Russian Far East; very often with the agreement of Russian provincial governments and local military forces who desperately needed cheap labor in order to develop this desolated land full of opportunities and natural resources.

Initially, the first Russian settlers in the Far East were quite hostile to unexpected newcomers. Koreans belonged to a different race, spoke an unfamiliar language, ate strange food, and had very different cultural habits.

Korean village near Vladivostok, Russia, at the beginning of the 20th century. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

However, and in spite of the initial hostility and ethnic discrimination against them, by the early 1900s the number of Koreans populating eastern Russia grew to almost 30,000 from the original 13 families found by a Russian military convoy along the Tizinhe River in 1863.

Subsequently, this number more than doubled after Korea became a Japanese protectorate in 1905 and a Japanese colony in 1910, and more than tripled by the early 1920s. With the Korean peninsula agonizing in a bloody turmoil, more and more Koreans helplessly fled to Russia.

After the Soviet revolution, all ethnic Koreans in the Russian Far East were issued Soviet citizenship. Most of their representations and activities, like local governments, schools, theaters, and newspapers, kept operating mostly in the Korean language.

Many Koreans became active contributors to the Soviet society. Nikolay’s grandfather Vasiliy Lee was one of them. Throughout the civil war in the Russian Far East from 1918 to 1922, he fought together with the Bolsheviks against the Japanese under the command of Sergey Lazo, who later became famous all over the Soviet Union.

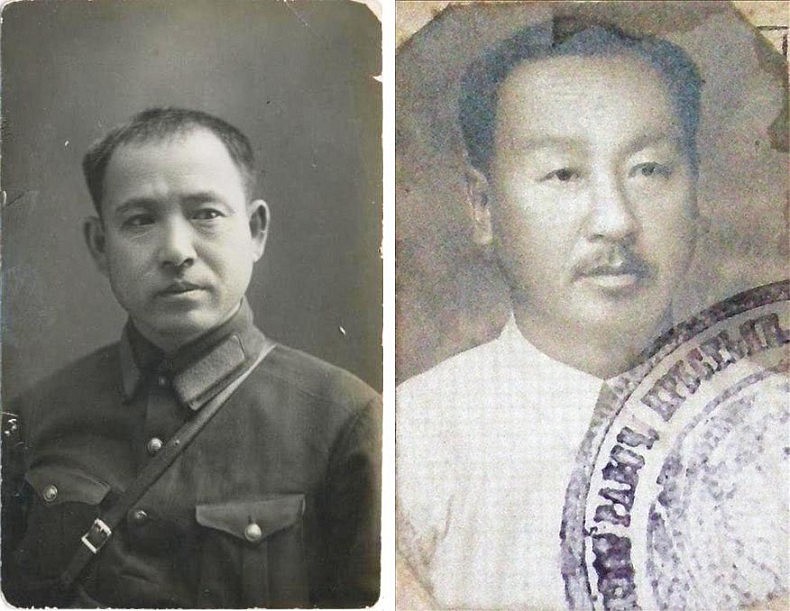

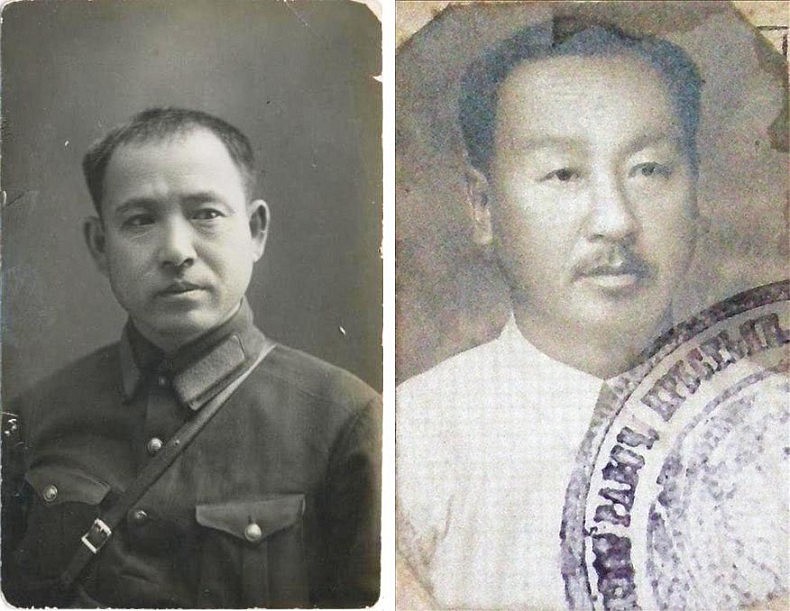

Left: Han Chan Ger, a famous Korean hero of the civil war in the Far East, 1918-1922.

Right: Park Gen Cher, another famous Korean hero of the civil war in the Far East. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

However, the fact that they truly hated the Japanese, who had colonized and brutalized their motherland, did not spare Soviet Koreans from their “dubious” ethnicity and “dangerous” links to Japan in the eyes of Soviet leadership.

Even before – by the end of the Russo-Japanese war in 1905 – Korean peasants in the Russian Far East were often kicked off the land they had cultivated, with anti-Korean laws applied against them since 1907.

In 1937, shortly after having conducted the official census that counted over 170,000 Koreans living in the Soviet Union in almost 40,000 families, the Soviet government was preparing another ordeal for them, much more horrid in its scope and future implications.

Young Soviet Korean university students in 1934, three years before the deportation. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Check back next week for part two of the series.

Acknowledgments: Part of the archival photography presented in this report on the Koreans in Soviet Uzbekistan, including several photographs by distinguished Uzbek Korean photographer Viktor An, were sourced from www.koryo-saram.ru and used in this multimedia project with the permission of the blog’s owner Vladislav Khan.

Please address all comments and questions about this story to vkimsky@gmail.com

This is the second in a three-part presentation of Victoria Kim’s multimedia report, created in memory of her Korean grandfather Kim Da Gir (1930-2007), which details the history and personal narratives of ethnic Koreans in Uzbekistan. It was originally published in November 2015 and is republished here with kind permission. Part one is here and part three here.

***

Vasiliy Lee

It was a dark and cold autumn night in 1937. Nikolay’s grandfather Vasiliy, his wife, and three daughters–Nikolay’s then-18-year-old mother Galina and her 24- and 20-year-old sisters–were all at home when someone suddenly knocked the door. They were from the Soviet secret police.

The order was simple and quick: “Gather all your belongings, personal documents, and all food you can find at home in less than half an hour and follow us immediately. You all are being deported.”

This is how it happened. The population of Posyet Korean national district – 171,781 ethnic Koreans from there and the rest of Soviet Far East – were put on cattle trains in a matter of hours at the beginning of the harsh Siberian winter, without much prior notice and with practically no food, water, warm clothes, or personal belongings.

All of them were being sent off to the Soviet Union’s first massive labor camps deep in Central Asia. Galina’s brother, Fedor Lee, was serving in the Soviet military at the time and was not deported with his family. (In part three, we’ll pick up what happened to Fedor).

The train journey was very long and exhausting. It lasted many weeks in dire cold, and the soldiers who guarded the cattle trains shared no food or water with the Korean deportees. In such conditions, people quickly died from malnutrition, and their bodies were left in the snow outside each train station.

During very brief stops at unfamiliar stations, the deportees tried to sell what little they had to locals or simply exchange their meager possessions for food. They also collected snow and melted it into water.

This is how Nikolay’s mother Galina and her two elder sisters survived, thanks to their parents’ ceaseless care and initial food supply from home. Nikolay’s grandparents gave away their own food and water to their three daughters. They didn’t last long and died on that train from starvation and weakness.

Their bodies were abandoned outside a small and unknown train station – one of many on the horrendous journey. Nobody knows the exact place of their final rest. Together with his wife, Vasiliy, a hero of the Soviet civil war in the Far East, forever disappeared in the snow.

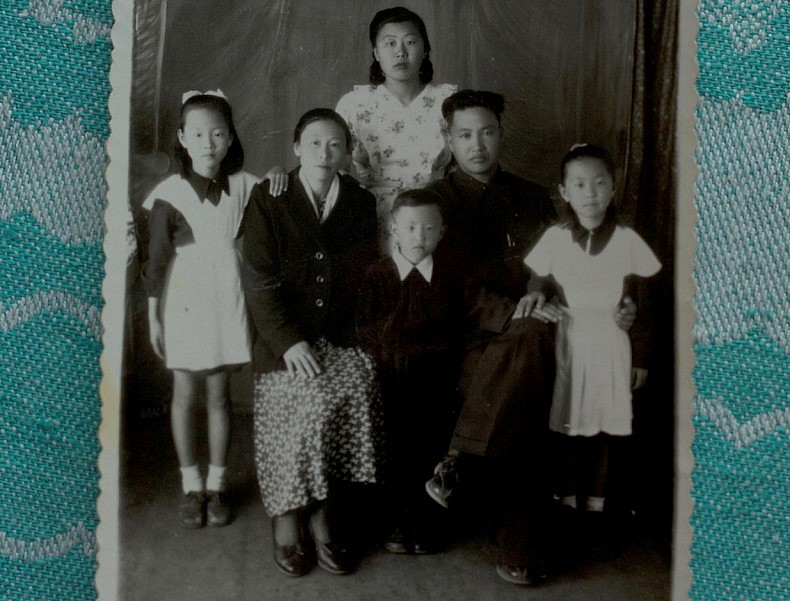

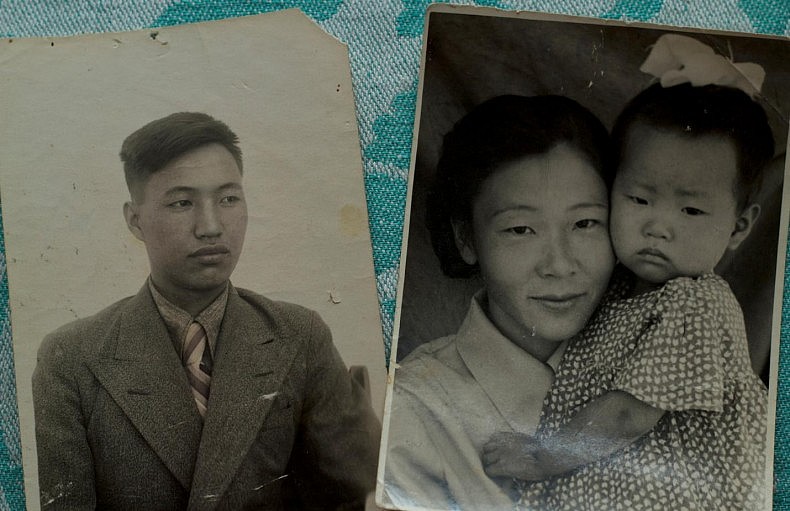

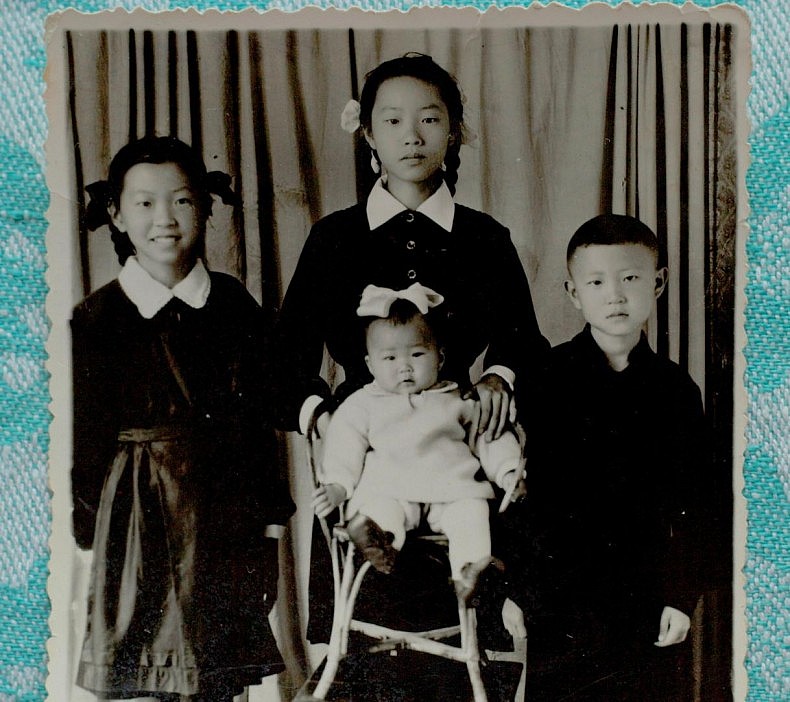

Konstantin Ten and Galina Lee, Nikolay’s parents, with his elder sister. Courtesy of Victoria Kim

Galina and Konstantin

Nikolay’s father Konstantin has also survived the journey, together with his parents and two brothers. He did not meet his future wife on the train. Instead, they met later upon their arrival to Uzbekistan.

When the Koreans arrived, they were lodged in special barracks under 24/7 armed guard. During the day, they worked drying wet swampland and rooting out the cane surrounding Uzbek capital Tashkent back then.

“It was a hell of a job,” Nikolay remembered from his parents’ stories. “There were a lot of wolves, jackals, and lynxes in the swampland. During the night, they would come very close to temporary shacks in the fields where the Koreans lived and scare everyone to death.”

Death was indeed crawling and waiting nearby, but in the form of much tinier creatures. The wet swampland was infested with malaria-ridden mosquitoes and many Koreans – unprotected and with no medicines at hand – got sick and died from malaria.

The swampland around Tashkent was first dried and then turned into rice fields. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Nevertheless, in fewer than five years after arriving in Soviet Uzbekistan, all the cane was rooted out and the swampland surrounding Tashkent was made arable. After they had completed this gigantic task, the Koreans were ordered to start growing rice on the new arable land in order to produce agricultural supply for the Soviet state.

Nikolay’s parents met and fell in love while working together in the fields. They got married in 1940 – she was 21 and he was 23. From the initial barracks and shacks under 24/7 armed guard, they eventually could move together into a tiny house they built themselves out of straw and mud.

All the rice they grew and harvested had to be given to the state. If any were caught trying to hide rice away, they would be judged guilty of collective property theft and go directly to prison.

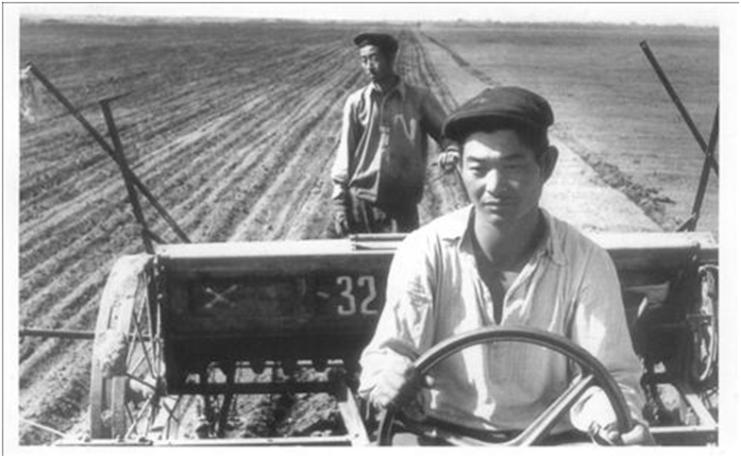

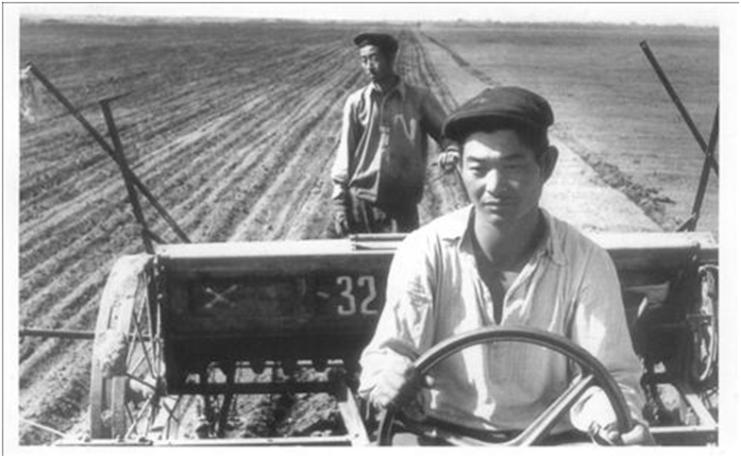

Korean kolkhoz farmers developing the arable land around Tashkent in the early 1940s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

The first Korean collective farms or kolkhozes were built around the very same rice fields the deportees had to farm and live on. They lived in tiny houses made of straw and mud instead of initial barracks and shacks.

Many got married and bore their children on this land, which also started to give its very first fruit. The armed guard control and passport restrictions lasted until it was understood the Koreans would not go anywhere.

In fact, they had nowhere else to go. With so many difficulties, they built their first houses and started their families in this foreign place that finally – slowly and painfully – became their own.

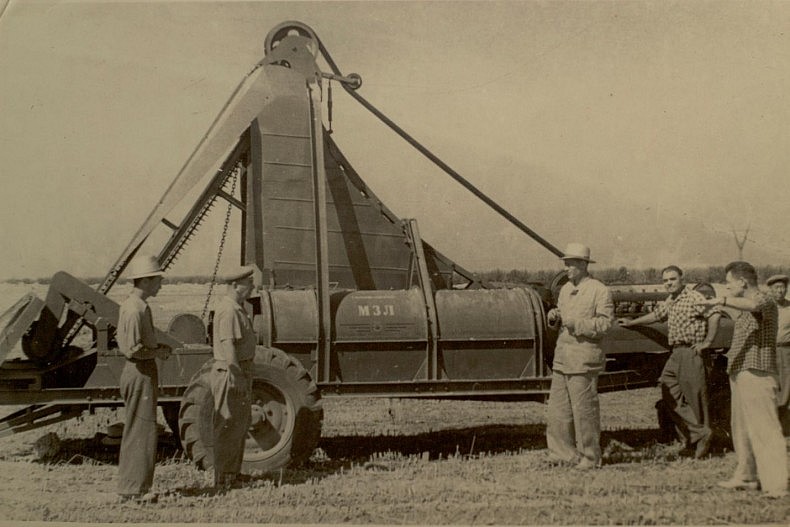

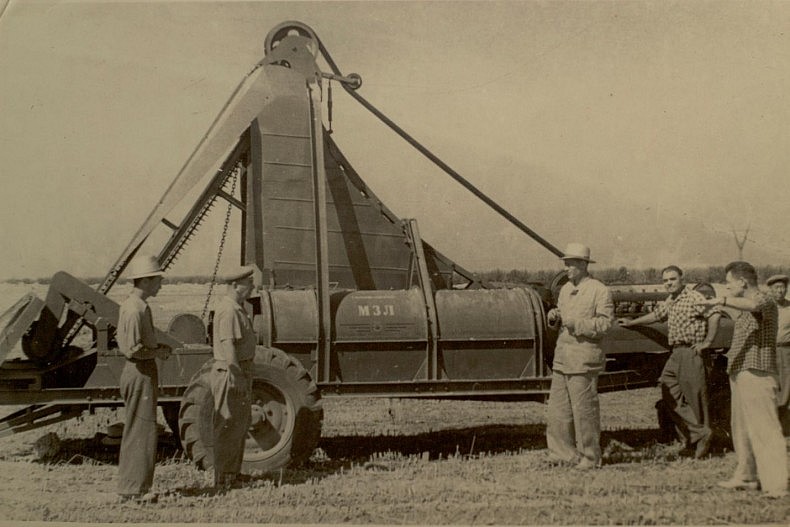

Crop harvesting in a Korean kolkhoz in the late 1950s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

After 1953

In late 1953, the death of Joseph Stalin marked the end of his personality cult and stopped the outright persecution of ethnic minorities. Many of Stalin’s policies were officially declared contradictory to the true principles of Leninism in 1956 and subsequently abandoned by a newly rising political leader, Nikita Khrushchev.

Pardoning all of the Soviet Union’s unwanted people and dissolving the infamous gulags – Siberian prison camps – were among Khrushchev’s first political decisions, taken to attempt to correct the mistakes of a very dark past.

Young and multi-ethnic Soviet citizens in Uzbekistan in the late 1950s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Finally, it looked like the Koreans were given a new chance to become legitimate Soviet citizens. Their children could now go to public primary, secondary, and vocational high schools and local universities. They could also move relatively freely within the Soviet Union and look for better professional opportunities.

Korean students at Nizami’s Tashkent State Pedagogic University. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Paradoxically, most of the Koreans stayed in the very same Korean kolkhozes they or their parents had built. Their living conditions were more stable as the years progressed. These were tight communities where everyone belonged to the same ethnic group and knew each other.

The children of the initial deportees were also coming back to the kolkhozes – often as graduates of prestigious state universities all over the Soviet Union– and given jobs in agricultural, managerial and technical positions.

The second generation of proud Uzbek Korean kolkhoz farmers. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Life slowly regained its normality. The first generations of Korean deportees had been trying very hard to forget their dark past, together with all its previous pain. They simply wanted to live happier lives, if not of their own then at least of their children.

A typical Korean family in a kolkhoz after 1956. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

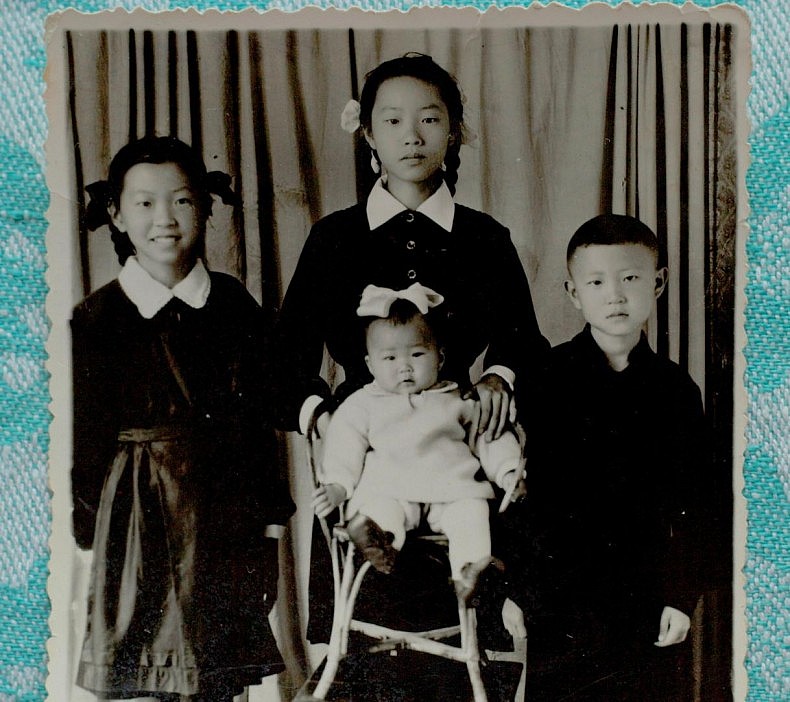

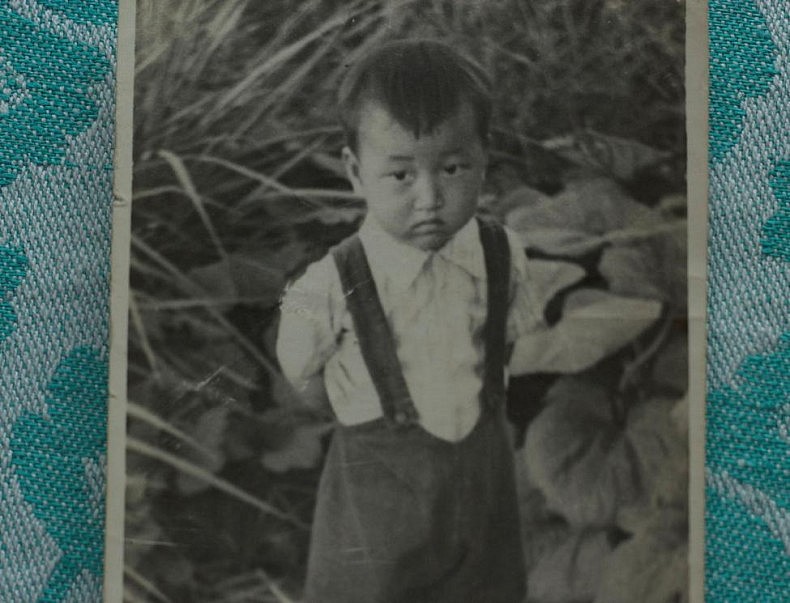

Young Nikolay Ten with his siblings. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Early Memories

Nikolay saw real bread for the first time in his life at the age of five. Before that his mother had always used compressed grass to “bake” bread of some kind. It was so heavy to digest that children often suffered from severe stomach aches, especially after eating a lot of it.

In the early 1950s they lived with constant food shortages: little Nikolay, his mother and two elder sisters (his third sister would be born ten years later).

“We had a cow, some chickens, and a pig. My dad had left to study at a pedagogical university, and my mother was left alone with three little children, taking care of our house and the animals.”

This is why she finally stopped working in the kolkhoz – there always was plenty of work at home. During the nights and after everyone had left to sleep, she was still awake, secretly sewing clothes, to be sold later to neighbors. All forms of private entrepreneurship were strictly prohibited back then by the Soviet state. Therefore, Galina’s nighttime work had to stay hidden.

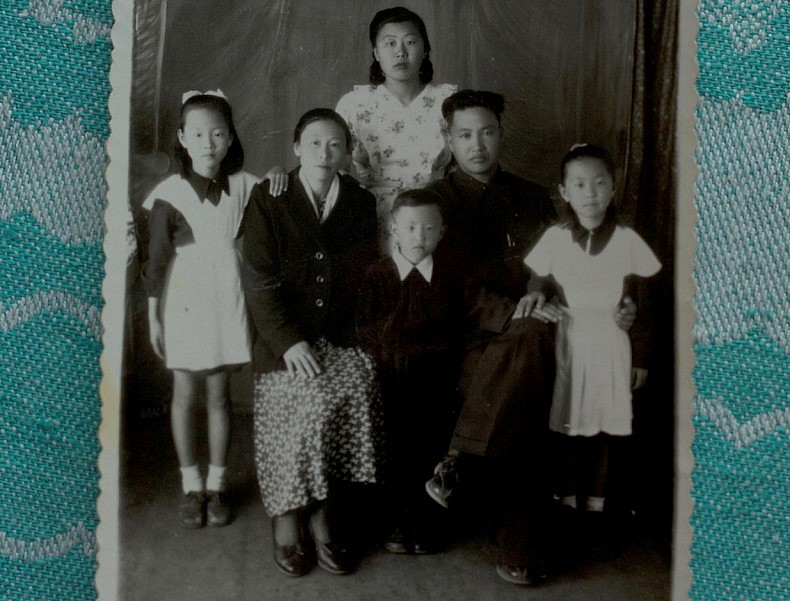

Galina Lee with her husband Konstantin Ten and children. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

“I was always playing outside the house as a little boy,” Nikolay remembers very emotionally, “and if I suddenly saw anyone around who didn’t look Korean, I would immediately run back to my mother and shout ‘Inspector is coming, inspector is coming!'”

Galina worked so hard during the day and in her nighttime shifts of sewing, that eventually it took a physical toll. “I had to start drinking cow milk way too early, because my mom was so stressed during the day and so tired of sleepless nights that there was no more milk left in her to feed me…”

Eventually, Galina was able to find a legal job in a state-owned tailor shop. Konstantin came back after finishing at university and became a math teacher at a local school. He worked as a math teacher for the rest of his life. They both were awarded with medals for their very hard lifelong labor.

Nikolay’s parents’ medals and state awards. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Next week we’ll wrap up the series with the story of Fedor Lee and also the fate of those who heeded the call to return to North Korea in the 1950s.

Acknowledgments: Part of the archival photography presented in this report on the Koreans in Soviet Uzbekistan, including several photographs by a distinguished Uzbek Korean photographer Viktor An, were sourced from www.koryo-saram.ru and used in this multimedia project with the permission of the blog’s owner Vladislav Khan.

---

Lost and Found in Uzbekistan: The Korean Story, Part 3

In the final chapters, the mystery of Fedor Lee is solved and some of the Uzbek Koreans return to North Korea.

By Victoria Kim

June 21, 2016

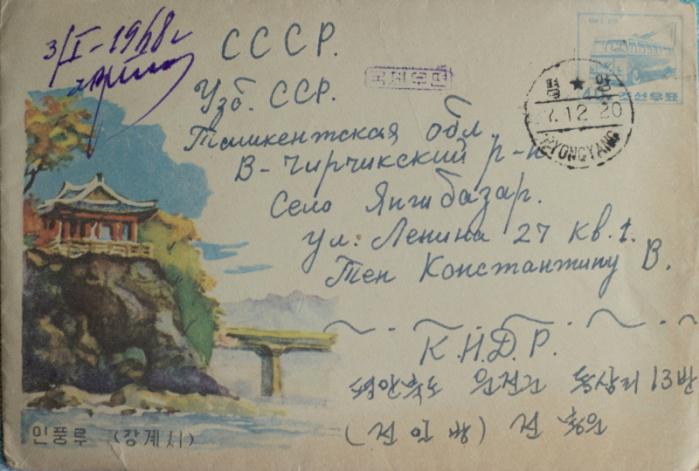

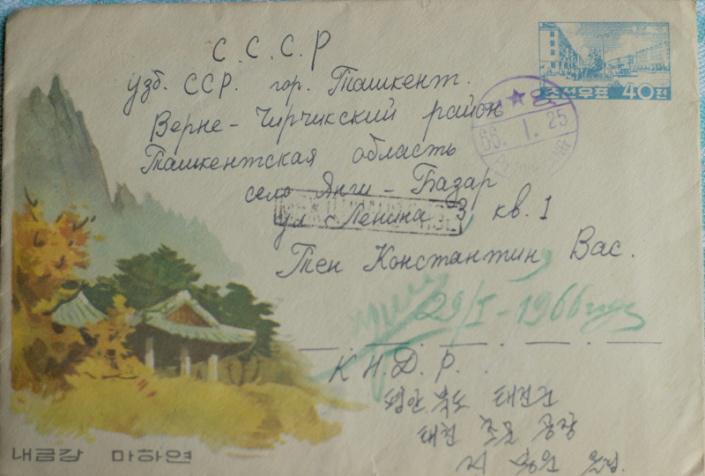

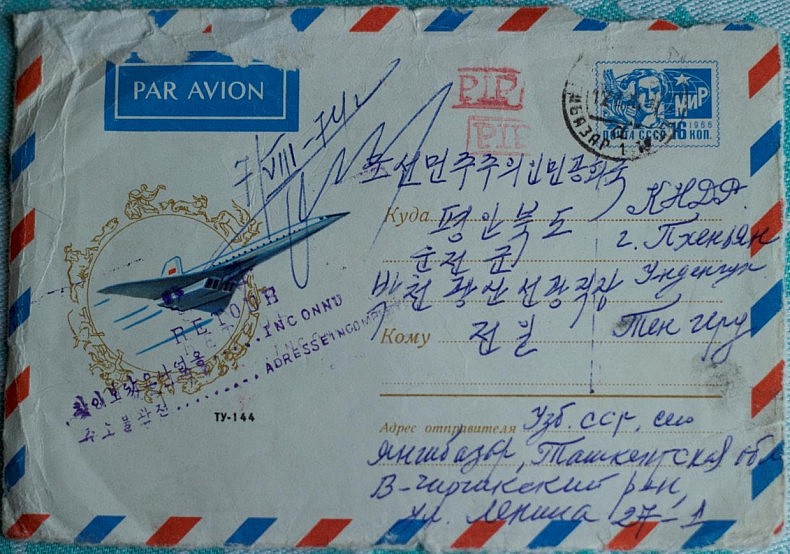

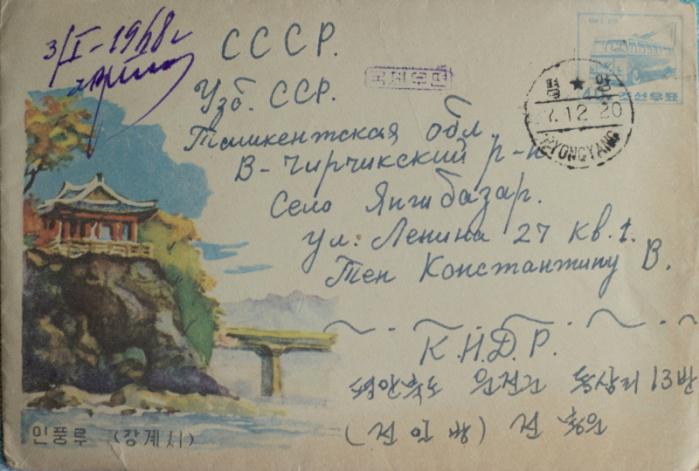

A festive postcard sent by little Lenya from the newly established DPRK back to Uzbekistan.Credit: Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

This is the third in a three-part presentation of Victoria Kim’s multimedia report, created in memory of her Korean grandfather Kim Da Gir (1930-2007), which details the history and personal narratives of ethnic Koreans in Uzbekistan. It was originally published in November 2015 and is republished here with kind permission. Read part one and part two.

***

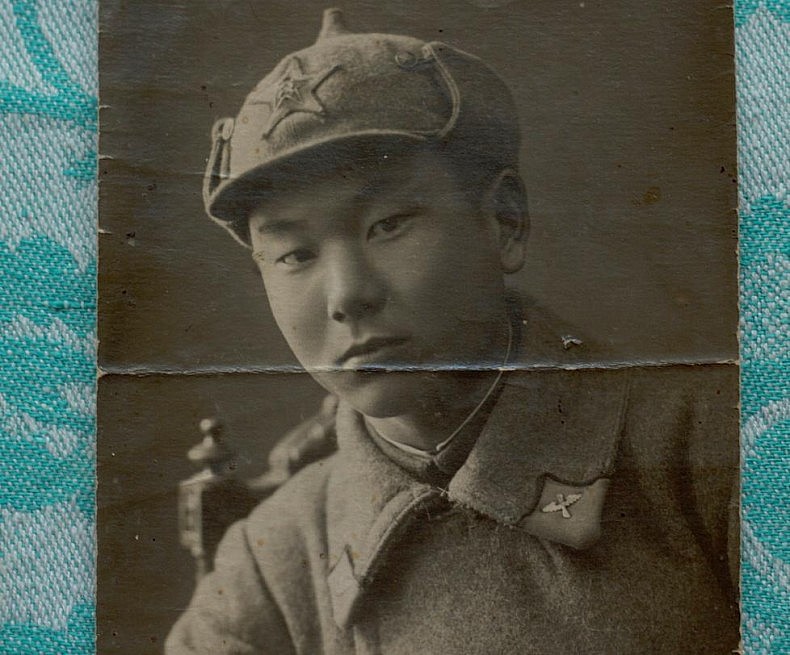

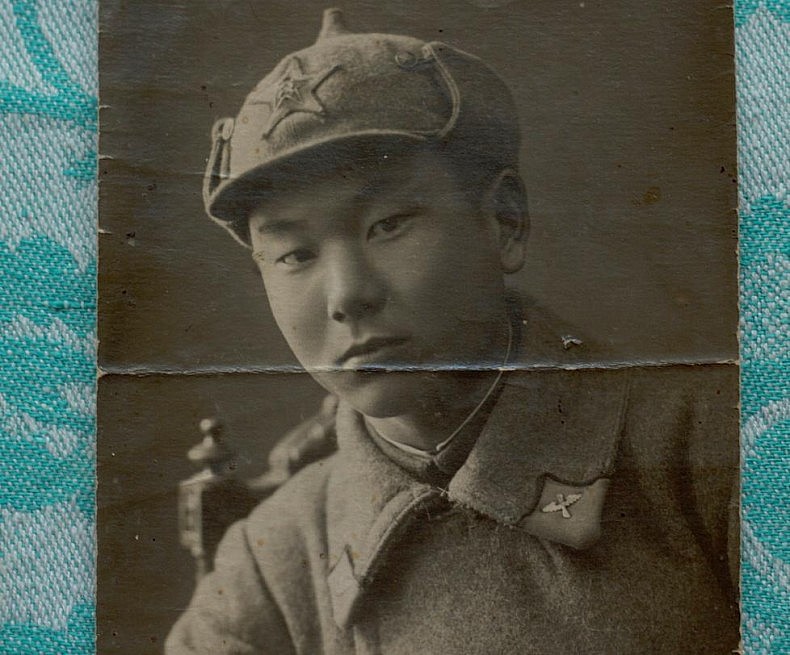

Fedor Lee in the Soviet army. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Fedor Lee

There is one memory that is especially painful for Nikolay. It is the memory of a very dark night back at home. He was still a very small child.

As a 3-year old, Nikolay could vividly remember everything around him. That night he was peacefully sleeping in his bed, when adult voices suddenly woke him up. Nikolay walked into the living room and saw a crying Korean stranger. He was telling something to Nikolay’s parents who were also crying while listening to him.

Nikolay still cries himself like a small child, telling me this story 60 years later.

When his mother came to Soviet Uzbekistan as a deportee in the cattle train together with her parents and sisters, her brother was left behind. He was only 21 and served in the Soviet military back in the Far East.

He was positioned in Kraskino town and separated from the rest of his family who lived in Crabs. When Stalin’s order for the deportation of Koreans came, he discovered that his whole family had been shipped to Uzbekistan on a train only very shortly before his own arrest.

As a soldier, Fedor Lee was under an even higher level of suspicion and scrutiny than the rest of the Koreans. According to the official version, he was accused by his neighbors of being a Japanese spy, declared a traitor and an enemy of the Soviet state.

Fedor was condemned to ten years of forced labor in the Siberian gulag in Komi Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. He did not last even through the first half of his imprisonment.

The Korean stranger who visited Nikolay’s family 15 years later was his uncle’s fellow prisoner in the gulag. He told Nikolay’s parents that Koreans were treated the worst by the guards among gulag prisoners, and only a couple of them survived the horrors of their imprisonment.

Every day they were sent to cut lumber deep in the Siberian woods, in spite of freezing temperatures, lack of warm clothes and malnutrition. Fedor badly injured his legs while cutting a tree, and in the cold weather developed gangrene. Even though he was unable to walk, Fedor’s comrade would remember, they still had to take him out to their working station, where he would cut branches from fallen trees.

After he got so weak that he could not work any longer, the prison guards shot him. It happened in the early 1940s, and nobody really knew where his body had been buried.

“My family was taken on a train all the way to Uzbekistan,” Fedor told his comrade shortly before dying. “If you manage to survive through all of this, please promise me you would go and find them… Please promise you would tell them my story, everything they have done to me.”

The comrade, whose name we will never know, fulfilled his promise to Fedor. He found Fedor’s family and came all the way to Uzbekistan to tell them everything that had happened.

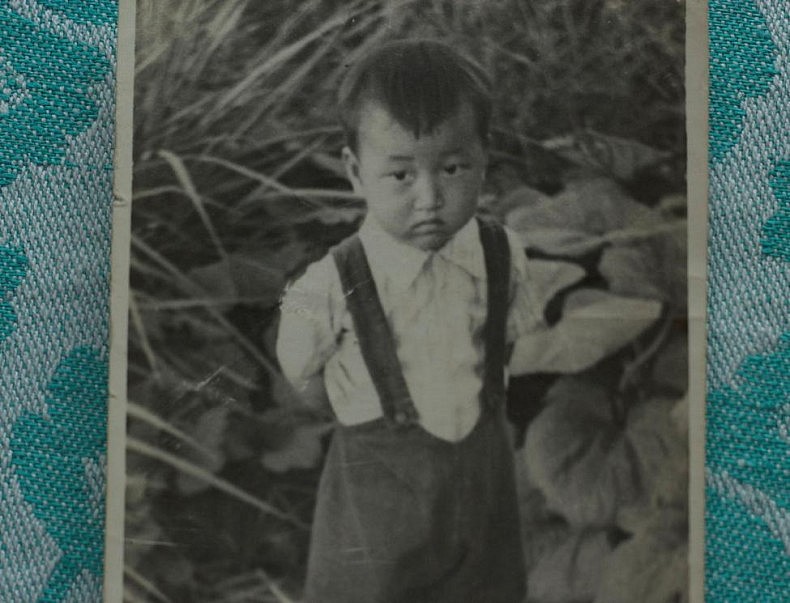

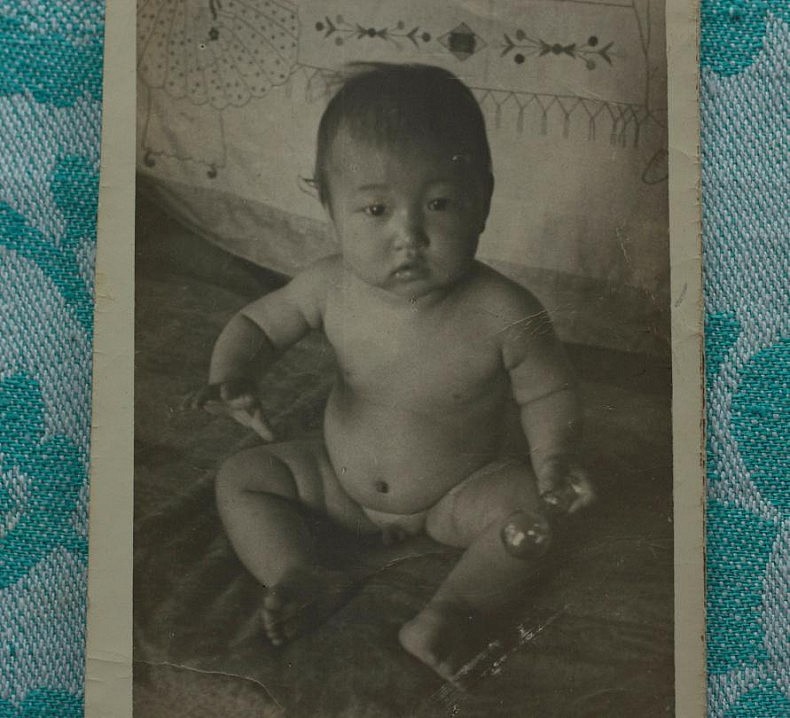

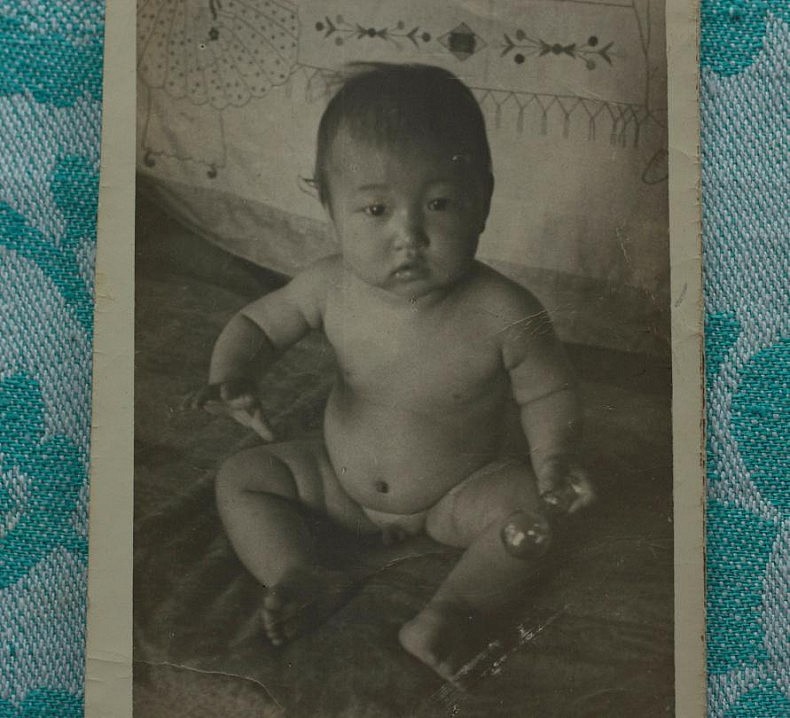

Alexey’s first son Leonid – one of the only photographic memories left of Alexey Ten. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Alexey Ten

It seems that in the lives of some there can never be too much suffering.

The lives of two generations–Nikolay’s grandparents and parents–bear clear signs of two waves of repressions against the ethnic Koreans and political prisoners of the Soviet state between the early 1930s and late 1950s.

There is, however, one more story left to tell. One more wave of repressions left to recount. This is one of – if not the most – secretive part of history in the lives of Soviet Koreans. This is the story not so many people happen to know about.

A secretive wave of repressions against Soviet Koreans in the DPRK (from the materials at the US Library of Congress)

Alexey Ten came to Uzbekistan on the same cattle train, together with his brother and Nikolay’s father Konstantin. Together they worked in the swampland and later rice fields, and then Alexey went to study in the Chirchiq military academy near Tashkent, where in the early 1950s he was approached with an unexpected order by his higher military command.

The special request came from the young Comrade Kim Il-sung, picked by Joseph Stalin in the indirect stand-off between the Soviet Union and United States over the Korean peninsula, to lead the North Korean communists. In the early 1950s, this stand-off led to the Korean War, which became known eventually in the West as the Forgotten War.

Back then, young and energetic Comrade Kim Il-sung sent a direct plea of help to all brotherly Soviet Koreans, asking those in the military ranks to fight the Korean War shoulder to shoulder with him in order to liberate the Korean peninsula from imperialist aggressors.

Many Uzbek Koreans from the Chirchiq military academy, together with other Central Asian Koreans, went and fought the Korean War shoulder to shoulder with Kim Il-sung, helping him to liberate North Korea and establish the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK).

Most of these Koreans stayed in North Korea afterwards as war heroes and Kim Il-sung’s closest friends and allies. They became generals, marshals, and admirals in the DPRK’s newly built military apparatus. Alexey Ten was among them – he became a general and the DPRK’s deputy minister of defense.

Alexey’s son Leonid or little Lenya. Courtesy of Victoria Ki.

Recognition at Last

Konstantin, Nikolay’s father, must have finally felt very happy for his brother – at last, he was in a very high and powerful position in a country that seemed to highly appreciate him. Earlier and while still living in Uzbekistan, Alexey Ten got married and had his first son Leonid, whom all of his brother’s family felt especially close to.

.

Later, after Alexey had fought together with Kim Il-sung in the Korean War , his family lived in North Korea. Alexey’s wife got badly ill with appendicitis and was operated on across the border from North Korea in the Chinese city of Harbin, but didn’t survive. Alexey eventually remarried a North Korean woman and had several more children with her; meanwhile his first son Leonid kept living with them in North Korea.

After the direct request from the Comrade Kim Il-sung, he and many other Uzbek Korean war heroes surrendered their Soviet citizenship in exchange for DPRK citizenship. The DPRK seemed to euphorically claim them back.

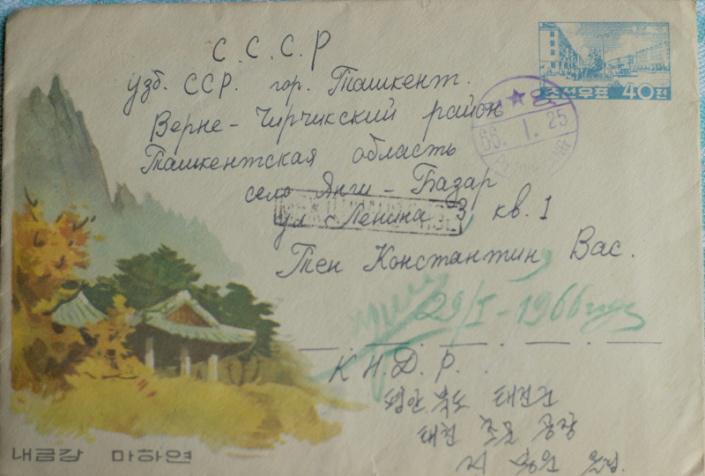

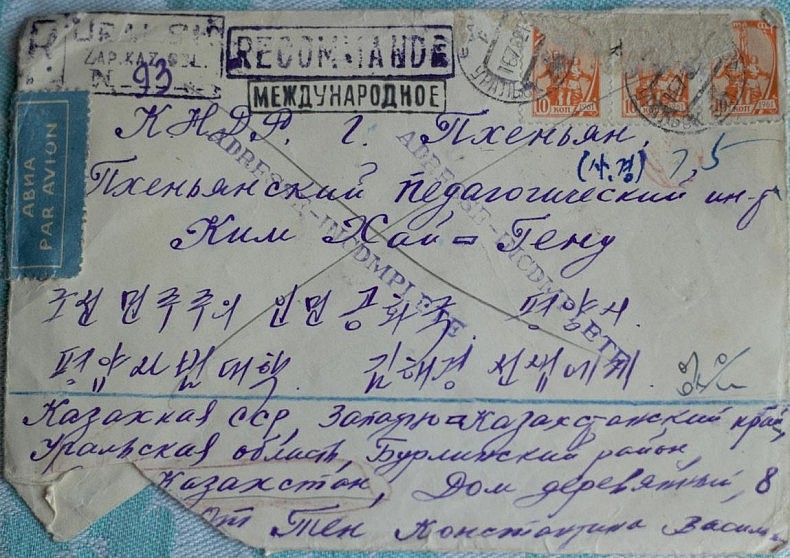

During this time, there was a unique exchange of letters going on between Upper Chirchiq in Uzbekistan and Pyongyang in North Korea, with the help of the North Korean Embassy in Moscow.

Konstantin, Nikolay’s father, would write to his brother Alexey or his nephew Leonid, always in Korean, and send his letters to the DPRK’s Moscow embassy, which would then pass them directly to General Chon Il Bang (the name Alexey Ten took) in Pyongyang, and vice versa.

Nikolay managed to keep some of the remaining letters, together with the photos of his cousin little Lenya.

Little Lenya’s postcard from North Korea to his uncle Konstantin. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

A colorful and happy postcard from Pyongyang signed with a trembling hand of the little child in broken Russian, wishing his cousins the best of luck and plenty of health. The lines in Korean from both brothers and little Lenya, who would always write all first names and some particular words in Russian, as if trying not to forget his mother language.

Konstantin’s letter to his brother Alexey in North Korea. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

The signature of the North Korean ambassador in Moscow, stating that he had indeed passed the letters between the recipients.

Those invisible ties that linked the Uzbek Koreans back to North Korea weren’t to last long. Nor was their euphoric success in the DPRK, a historical motherland they were so happy and proud to help rebuild, to be anything but brief.

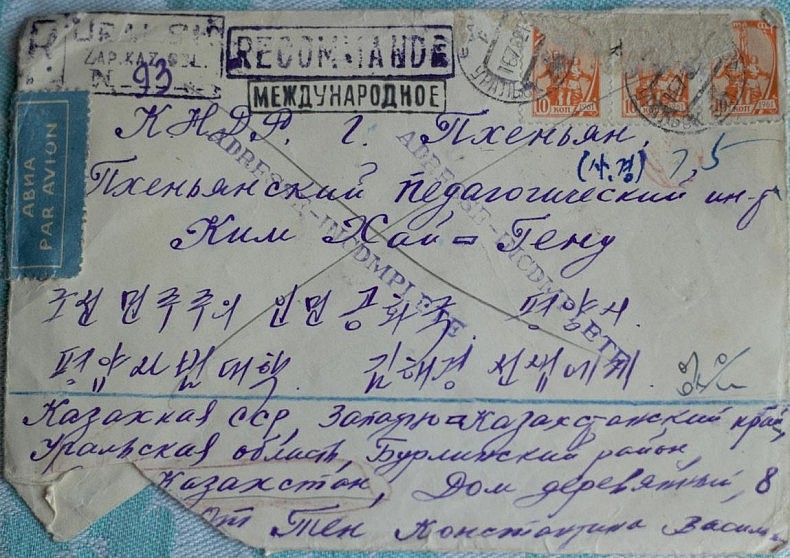

Konstantin’s letter to Pyongyang, returned with a stamp “Incomplete address.” Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Recipient Unknown

In 1953, upon the death of Joseph Stalin and the demolition of his personality cult as contradicting to the true principles of Leninism, the relationship between North Korea and the Soviet Union started to deteriorate.

Kim Il-sung, who adopted the system of adoration and political reprisals from his own beloved Great Leader, felt vulnerable after Stalin’s defamation in the USSR and started suspecting the new Soviet command of plotting to destroy him in a direct coup d’etat.

Among the first to blame for the same old sins – political and military treason, espionage, and animosity to the DPRK – were the same Soviet Koreans who again and again found themselves between the wheels of ruthless state machinery bound to destroy them.

Purges began one by one against Kim Il-sung’s closest friends, former fellows, and allies. The DPRK’s highest military apparatus consisting mostly of Soviet Korean ministers, deputy ministers, generals, marshals, and admirals was soon and completely eradicated.

It looked like Kim Il-sung was trying to change the past and make it seem as if the years between the 1940s and 1960s had never existed. He did everything possible to wipe out the entire memory of the traitors who had given him and their historical motherland everything, up to their own lives.

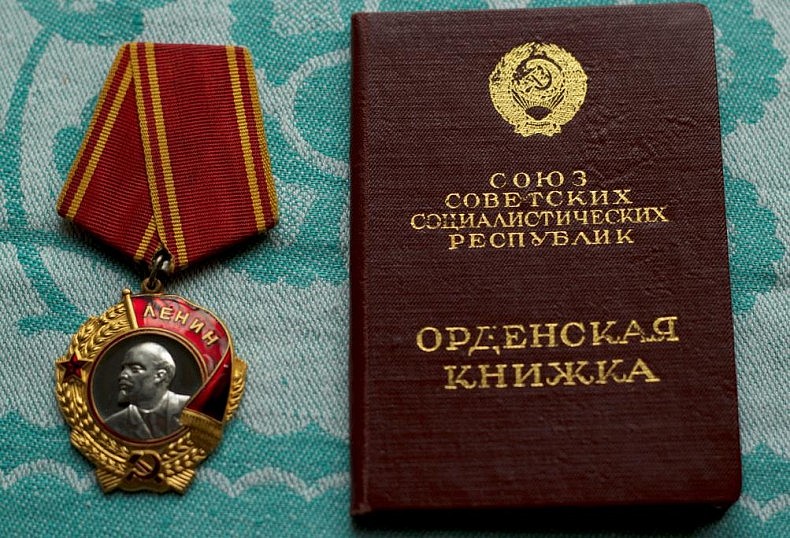

Suddenly, Konstantin’s letters started returning from the Moscow-based North Korean embassy with a weird stamp: “Recipient unknown.”

Recipient unknown, Konstantin’s letter returned from North Korea. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Alexey’s postal address simply ceased to exist. Nobody could explain anything. Konstantin kept sending letters, and the letters kept coming back with the same postal stamp, “recipient unknown.” This lasted until Konstantin, exhausted and anguished, managed to talk directly to the North Korean ambassador in Moscow, who finally explained everything.

“Don’t look for your brother any longer. Stop sending him those letters. There is no way to find him or his family now. They have been purged as traitors, spies, and enemies of the state, and we know nothing about them at this point. And, probably, we will never know.”

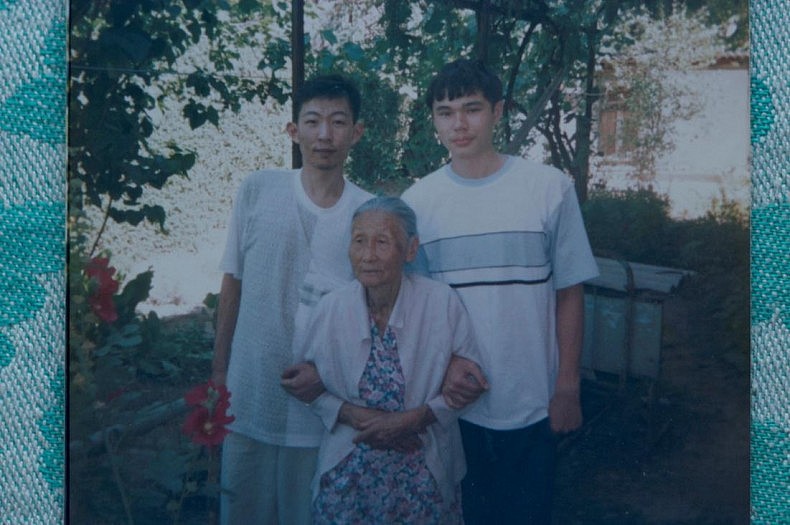

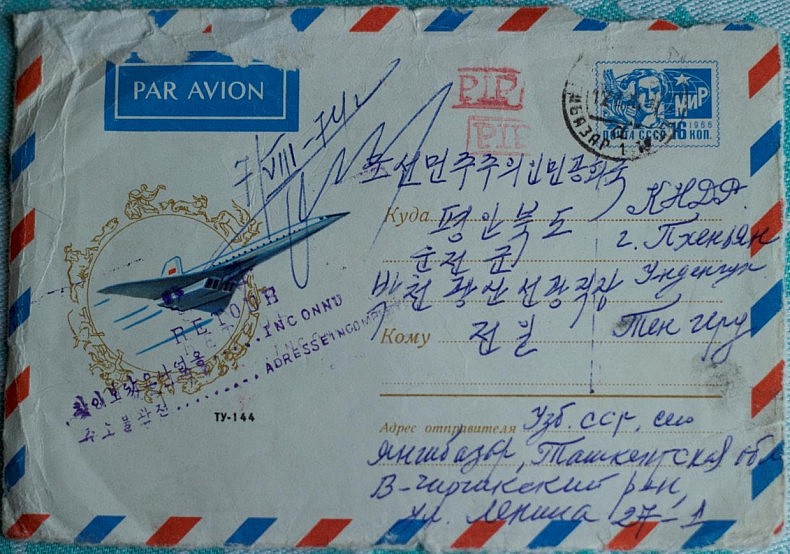

Galina Lee and her grandchildren. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Post Scriptum

How many cycles of repression can one survive? How many tears can one cry? How many family members can one lose? And the most important question – what for and whose fault is it that such atrocities keep happening?

The Soviet Koreans, Uzbek Koreans, Koreans kept spinning again and again, crushed between the wheels of history, betrayed and dishonored again and again by a foreign motherland. How many motherlands can one lose and how many of them can one get?

Lenin medal and certificate book. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

And what is it worth, after all, when at the end the only thing you are bound to be is homeless, forgotten, and dishonored? Nikolay’s parents could never answer those questions. Have they even asked them?

Nikolay answers my question this time. “Have they ever blamed Joseph Stalin or the Soviet state for what it had done to them? Maybe, they did. Probably so. I don’t really know, because they were never free to talk about it, even with us. I don’t blame anyone any longer. I simply hope such atrocities will never happen again.”

Galina Lee with her children – Nikolay Ten and his three sisters. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Part of the archival photography presented in this report on the Koreans in Soviet Uzbekistan, including several photographs by a distinguished Uzbek Korean photographer Viktor An, were sourced from www.koryo-saram.ru and used in this multimedia project with the permission of the blog’s owner Vladislav Khan.

---

Lost and Found in Uzbekistan: The Korean Story, Part 1

Victoria Kim, in looking into her own history, dives into the story of how Koreans came to Uzbekistan.

By Victoria Kim

June 08, 2016

Korean, Russian, Tatar, Ukrainian and Uzbek kids all together in a class photo (Tashkent in the early 1940s)Credit: Courtesy of Victoria KimADVERTISEMENT

This is the first in a three-part presentation of Victoria Kim’s multimedia report, created in memory of her Korean grandfather Kim Da Gir (1930-2007), which details the history and personal narratives of ethnic Koreans in Uzbekistan. It was originally published in November 2015 and is republished here with kind permission. Make sure to read part two and part three.

***

“The personal story of my family is at the same time the story of suffering of all Korean people… I want to tell this story to the world, so that nothing like that ever happens again in our future.”

— Nikolay Ten

***

My mom, a half-Korean child among multi-ethnic kids from all over Soviet Union in a Tashkent kindergarten in the early 1960s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Introduction

Strolling along the streets of Tashkent or riding in a small marshrutka minibus – a common mode of transportation in this busy and bustling Central Asian city with a population of about 3 million people – you would feel no surprise looking at the multitude of different faces.

Tanned and dark haired or white skinned and blond, with blue, green, or brown eyes, Russians, Tatars, or Koreans would always appear in the crowd of local Uzbeks. There used to be even more of them here several decades ago, living together in this calm and friendly city full of sunshine and welcoming shade.

A true friendship of people in Tashkent in the late 1960s: Russians, Tartars. and Koreans together, having a rest near the Karasu river. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

By now, many people have left together with their untold stories about this capital of “sun and bread,” a Soviet-day Babylon that became a true Noah’s ark hosting and hiding the survivors of a horrifying storm of ethnic repressions.

Here, lost deep in the heart of a Central Asian desert, they multiplied, prospered and lived in peace. Russians, Jews, Germans, Armenians, Meskhetian Turks, Chechens, Crimean Tatars, and Greeks — most of them had found a second home here, temporary if not permanent.

After the Soviet Union’s breakup in 1991, many ethnic groups abandoned this newly rising and predominantly Muslim country. Some feared possible persecution — which fortunately never happened — while others simply followed their own practical reasons and departed.

Some left earlier, as soon as the restrictions on their movement were lifted in the wave of so called “democratization” early in the 1970s.

However, there was one particular community of people that chose to stay in Uzbekistan. They actually had nowhere else to go. Through the years of pain and suffering, hard physical labor, adaptation, and assimilation, this country had become their one and only true home.

These people are Uzbek Koreans, and this story is about them.

Left: Park Ken Dyo, the creator of kendyo type of rice that rose him to prominence in Soviet Uzbekistan.

Right: A Korean farmer in Soviet Uzbekistan. Courtesy of Victoria Kim

Young Nikolay Ten. Courtesy of Victoria Kim

Nikolay Ten

Nikolay and I were simply bound to meet. When I first saw him on the calm and quiet streets of Tashkent in the early spring of 2014, he was selling souvenirs, antiques, and traditional Uzbek clay figurines to passersby and tourists in the central city square formerly known as Broadway.

Passersby and tourists looking for traditional Uzbek souvenirs on Broadway in Tashkent. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

The several theaters it used to host were long gone, as were the crowds. The name has somehow stuck, adding nostalgia and curious mystery to this huge and otherwise deserted area full of flowerbeds and monuments to fallen heroes.

Only a handful of artists, painters and antiquity collectors remained here, including Nikolay, a small and aging Korean man who would pass anywhere for a “typical” Central Asian. He looked more like a Kyrgyz, Kazakh, or Mongol, with his bald head and dark skin tanned by the sun.

Nikolay on the day I met him on Broadway in Tashkent in the early spring 2014. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Something very special on his smooth and round face was his smile – the kind, honest, and hesitant smile of a thoughtful child that he still kept somewhere deep in his heart.

I bounced into Nikolay in the middle of my own personal quest. I was looking for a story almost disappeared and now hidden somewhere near. The ghosts of our recent past were haunting me from all sides on that warm and cloudy spring day on Broadway, and probably, they brought me to Nikolay and made him reveal his story to me.

Uzbek Koreans in the late 1940s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

At the same time, the urge to keep telling this story is somehow very understandable for both of us. These are our collective memories, imprinted in the genes of all Uzbek Koreans.

They are still kept in the taste of pigodi, chartagi, khe, or kuksi – a handful of salty and spicy North Korean dishes that have become a representative part of our vibrant and mixed Uzbek cuisine.

Local Korean sellers at a typical Korean salad stand in Tashkent. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

They still resonate in the sound of a few remaining words in the Hamgyong dialect, which Soviet Koreans originally spoke when they first arrived to Uzbekistan in 1937. They still mark our ancient lunar calendar during the traditional holidays, such as Hansik and Chusok – spring and autumn equinoxes – or tol and hwangab, the auspicious first and sixtieth birthday celebrations.

These ancient and typically Korean festivities and cultural rituals have somehow survived all former official prohibitions and are vigorously observed across Uzbekistan by one unique ethnic group.

This very tight community also shares a deeply secretive history known through the tragic accounts of past persecutions, repressions, and deaths. These stories would only be told to close relatives and passed among family members, from one generation to another.

The sufferings those stories unveil are always very deep. Equally deep is the pain the memories still provoke.

My then-young grandfather Kim Da Gir. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

My Grandfather

I also have a story woven into the secrets of this tragic past. A long time ago, my grandfather told it to me only once and never wanted to speak about it again.

This is the story of a little boy who traveled one cold winter with many other people, all stuck together inside a dark and stinking cattle train. He traveled on that train together with his parents and siblings for many weeks, until one day they arrived to a strange place in the middle of nowhere.

A map showing the forced relocation of “unwanted” ethnic minorities in the Soviet Union throughout the late 1930s – early 1940s. Koreans were the first entire nationality to get deported in 1937 from the Soviet Far East to Central Asia. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

That place was somewhere in Soviet Uzbekistan. It was 1937, and my grandfather was only seven years old.

What brought him to empty and deserted Central Asia was the first Soviet deportation of an entire nationality. What united all of them as the victims of this massive deportation was their ethnicity. They all happened to be Koreans.

The cattle train story was the only thing my grandfather ever told me about those painful and complicated times. Yet all his untold stories would keep haunting me later on, as would his very apparent Korean appearance and our Korean last name.

In order to affirm my partly Korean belonging I eventually studied Korean, or rather its classical Seoul dialect, which my grandfather was never be able to understand.

Studying Korean together with my Korean classmates in Tashkent in the early 2000s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

I would keep looking for any affinity with Korea and even graduated in the Korean studies at a renowned university in the United States, which my grandfather happily lived to know.

So far from my actual Korean roots and never at peace with this understanding, I would keep looking for those unique Korean stories forgotten and lost deep in Central Asian sands. It would become my personal quest to uncover the secret spaces left blank on purpose, in our family history and in the history of all Uzbek Koreans.

Uzbek Korean heroes of socialist labor in the late 1940s – early 1950s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

My grandfather lived a relatively successful life in Uzbekistan. He went to study in Moscow and was later sent to work in rural Ukraine, where he met his future Russian wife, a woman who was working in the same town. They returned to Tashkent together in 1957, already married and with my one-year-old mother.

For most of his life, my grandfather worked as a chief engineer in the construction bureau at a major industrial plant in Tashkent. He developed and patented a lot of technical innovations for cotton picking machinery – we still keep all his certificates of achievement at home.

This is how the Korean community is ingrained in our social fabric – as extremely hard working people and quite a prosperous diaspora. In fact, many Koreans – including Nikolay’s mother and my grandfather – have been awarded with numerous state medals for their very hard labor during the Soviet times.

Uzbek Koreans are also known for their indisputable role in the development of Uzbekistan’s national agriculture. Traditional peasants, they passed to Uzbek locals their generations-worth of farming knowledge and techniques. Even now, the best types of rice grown in Uzbekistan and used in the preparation of most representative Uzbek dishes are still lovingly called “Korean.”

My grandfather (in the center) with his colleagues from the construction bureau. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

However, little is known about the heavy toll Uzbek Koreans had to pay in order to gain such a high reputation in our society. They were forced to come to Uzbekistan, they had to develop it and turn into their own, they bore children upon it and – very slowly – it became their one and only home.

Nikolay and I are desperate to preserve our history – in the name of all Korean people. This is the story of three generations of his family. It is also my grandfather’s story. Nikolay and I are determined to keep it alive, so the history may never repeat itself.

Soviet Koreans while being deported from the Far East to Central Asia in 1937. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

At least, we truly hope so.

Before 1937

Nikolay’s mother was born in 1919 in Maritime province (Primorsky Krai), in the village called Crabs. Back then it belonged to Posyet national district, and the whole territory of this province was an official part of the Soviet Far East.

In fact, this tiny piece of land – stuck between northeastern China and the upper tip of present-day North Korea on one side, and surrounded with the Japanese Sea on the other – used to serve as a buffer zone for the Soviets throughout most of the 1920s.

Posyet in the early 1900s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Koreans originally started moving here in the late 19th century, escaping harsh living conditions, poverty and starvation in the north of the Korean peninsula. They built the first Korean villages and towns in the Russian Far East; very often with the agreement of Russian provincial governments and local military forces who desperately needed cheap labor in order to develop this desolated land full of opportunities and natural resources.

Initially, the first Russian settlers in the Far East were quite hostile to unexpected newcomers. Koreans belonged to a different race, spoke an unfamiliar language, ate strange food, and had very different cultural habits.

Korean village near Vladivostok, Russia, at the beginning of the 20th century. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

However, and in spite of the initial hostility and ethnic discrimination against them, by the early 1900s the number of Koreans populating eastern Russia grew to almost 30,000 from the original 13 families found by a Russian military convoy along the Tizinhe River in 1863.

Subsequently, this number more than doubled after Korea became a Japanese protectorate in 1905 and a Japanese colony in 1910, and more than tripled by the early 1920s. With the Korean peninsula agonizing in a bloody turmoil, more and more Koreans helplessly fled to Russia.

After the Soviet revolution, all ethnic Koreans in the Russian Far East were issued Soviet citizenship. Most of their representations and activities, like local governments, schools, theaters, and newspapers, kept operating mostly in the Korean language.

Many Koreans became active contributors to the Soviet society. Nikolay’s grandfather Vasiliy Lee was one of them. Throughout the civil war in the Russian Far East from 1918 to 1922, he fought together with the Bolsheviks against the Japanese under the command of Sergey Lazo, who later became famous all over the Soviet Union.

Left: Han Chan Ger, a famous Korean hero of the civil war in the Far East, 1918-1922.

Right: Park Gen Cher, another famous Korean hero of the civil war in the Far East. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

However, the fact that they truly hated the Japanese, who had colonized and brutalized their motherland, did not spare Soviet Koreans from their “dubious” ethnicity and “dangerous” links to Japan in the eyes of Soviet leadership.

Even before – by the end of the Russo-Japanese war in 1905 – Korean peasants in the Russian Far East were often kicked off the land they had cultivated, with anti-Korean laws applied against them since 1907.

In 1937, shortly after having conducted the official census that counted over 170,000 Koreans living in the Soviet Union in almost 40,000 families, the Soviet government was preparing another ordeal for them, much more horrid in its scope and future implications.

Young Soviet Korean university students in 1934, three years before the deportation. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Check back next week for part two of the series.

Acknowledgments: Part of the archival photography presented in this report on the Koreans in Soviet Uzbekistan, including several photographs by distinguished Uzbek Korean photographer Viktor An, were sourced from www.koryo-saram.ru and used in this multimedia project with the permission of the blog’s owner Vladislav Khan.

Please address all comments and questions about this story to vkimsky@gmail.com

TAGS

Crossroads Asia

ethnic Koreans in Uzbekistan

South Korea-Uzbekistan relations

Soviet Union

Soviet Union deportations

Uzbekistan

---

Lost and Found in Uzbekistan: The Korean Story, Part 2

The story continues as the Koreans transition through life in forced labor camps to building new lives in Uzbekistan.

By Victoria Kim

June 14, 2016

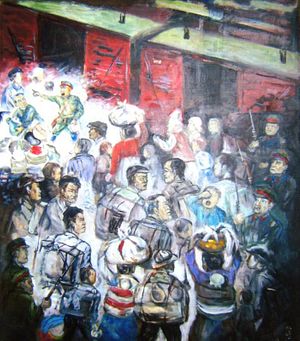

The deportation of Koreans from the Soviet Far East to Central Asia in 1937 (as imagined by a Korean painter).Credit: Courtesy of Victoria Kim

Crossroads Asia

ethnic Koreans in Uzbekistan

South Korea-Uzbekistan relations

Soviet Union

Soviet Union deportations

Uzbekistan

---

Lost and Found in Uzbekistan: The Korean Story, Part 2

The story continues as the Koreans transition through life in forced labor camps to building new lives in Uzbekistan.

By Victoria Kim

June 14, 2016

The deportation of Koreans from the Soviet Far East to Central Asia in 1937 (as imagined by a Korean painter).Credit: Courtesy of Victoria Kim

This is the second in a three-part presentation of Victoria Kim’s multimedia report, created in memory of her Korean grandfather Kim Da Gir (1930-2007), which details the history and personal narratives of ethnic Koreans in Uzbekistan. It was originally published in November 2015 and is republished here with kind permission. Part one is here and part three here.

***

Vasiliy Lee

It was a dark and cold autumn night in 1937. Nikolay’s grandfather Vasiliy, his wife, and three daughters–Nikolay’s then-18-year-old mother Galina and her 24- and 20-year-old sisters–were all at home when someone suddenly knocked the door. They were from the Soviet secret police.

The order was simple and quick: “Gather all your belongings, personal documents, and all food you can find at home in less than half an hour and follow us immediately. You all are being deported.”

This is how it happened. The population of Posyet Korean national district – 171,781 ethnic Koreans from there and the rest of Soviet Far East – were put on cattle trains in a matter of hours at the beginning of the harsh Siberian winter, without much prior notice and with practically no food, water, warm clothes, or personal belongings.

All of them were being sent off to the Soviet Union’s first massive labor camps deep in Central Asia. Galina’s brother, Fedor Lee, was serving in the Soviet military at the time and was not deported with his family. (In part three, we’ll pick up what happened to Fedor).

The train journey was very long and exhausting. It lasted many weeks in dire cold, and the soldiers who guarded the cattle trains shared no food or water with the Korean deportees. In such conditions, people quickly died from malnutrition, and their bodies were left in the snow outside each train station.

During very brief stops at unfamiliar stations, the deportees tried to sell what little they had to locals or simply exchange their meager possessions for food. They also collected snow and melted it into water.

This is how Nikolay’s mother Galina and her two elder sisters survived, thanks to their parents’ ceaseless care and initial food supply from home. Nikolay’s grandparents gave away their own food and water to their three daughters. They didn’t last long and died on that train from starvation and weakness.

Their bodies were abandoned outside a small and unknown train station – one of many on the horrendous journey. Nobody knows the exact place of their final rest. Together with his wife, Vasiliy, a hero of the Soviet civil war in the Far East, forever disappeared in the snow.

Konstantin Ten and Galina Lee, Nikolay’s parents, with his elder sister. Courtesy of Victoria Kim

Galina and Konstantin

Nikolay’s father Konstantin has also survived the journey, together with his parents and two brothers. He did not meet his future wife on the train. Instead, they met later upon their arrival to Uzbekistan.

When the Koreans arrived, they were lodged in special barracks under 24/7 armed guard. During the day, they worked drying wet swampland and rooting out the cane surrounding Uzbek capital Tashkent back then.

“It was a hell of a job,” Nikolay remembered from his parents’ stories. “There were a lot of wolves, jackals, and lynxes in the swampland. During the night, they would come very close to temporary shacks in the fields where the Koreans lived and scare everyone to death.”

Death was indeed crawling and waiting nearby, but in the form of much tinier creatures. The wet swampland was infested with malaria-ridden mosquitoes and many Koreans – unprotected and with no medicines at hand – got sick and died from malaria.

The swampland around Tashkent was first dried and then turned into rice fields. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Nevertheless, in fewer than five years after arriving in Soviet Uzbekistan, all the cane was rooted out and the swampland surrounding Tashkent was made arable. After they had completed this gigantic task, the Koreans were ordered to start growing rice on the new arable land in order to produce agricultural supply for the Soviet state.

Nikolay’s parents met and fell in love while working together in the fields. They got married in 1940 – she was 21 and he was 23. From the initial barracks and shacks under 24/7 armed guard, they eventually could move together into a tiny house they built themselves out of straw and mud.

All the rice they grew and harvested had to be given to the state. If any were caught trying to hide rice away, they would be judged guilty of collective property theft and go directly to prison.

Korean kolkhoz farmers developing the arable land around Tashkent in the early 1940s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

The first Korean collective farms or kolkhozes were built around the very same rice fields the deportees had to farm and live on. They lived in tiny houses made of straw and mud instead of initial barracks and shacks.

Many got married and bore their children on this land, which also started to give its very first fruit. The armed guard control and passport restrictions lasted until it was understood the Koreans would not go anywhere.

In fact, they had nowhere else to go. With so many difficulties, they built their first houses and started their families in this foreign place that finally – slowly and painfully – became their own.

Crop harvesting in a Korean kolkhoz in the late 1950s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

After 1953

In late 1953, the death of Joseph Stalin marked the end of his personality cult and stopped the outright persecution of ethnic minorities. Many of Stalin’s policies were officially declared contradictory to the true principles of Leninism in 1956 and subsequently abandoned by a newly rising political leader, Nikita Khrushchev.

Pardoning all of the Soviet Union’s unwanted people and dissolving the infamous gulags – Siberian prison camps – were among Khrushchev’s first political decisions, taken to attempt to correct the mistakes of a very dark past.

Young and multi-ethnic Soviet citizens in Uzbekistan in the late 1950s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Finally, it looked like the Koreans were given a new chance to become legitimate Soviet citizens. Their children could now go to public primary, secondary, and vocational high schools and local universities. They could also move relatively freely within the Soviet Union and look for better professional opportunities.

Korean students at Nizami’s Tashkent State Pedagogic University. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Paradoxically, most of the Koreans stayed in the very same Korean kolkhozes they or their parents had built. Their living conditions were more stable as the years progressed. These were tight communities where everyone belonged to the same ethnic group and knew each other.

The children of the initial deportees were also coming back to the kolkhozes – often as graduates of prestigious state universities all over the Soviet Union– and given jobs in agricultural, managerial and technical positions.

The second generation of proud Uzbek Korean kolkhoz farmers. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Life slowly regained its normality. The first generations of Korean deportees had been trying very hard to forget their dark past, together with all its previous pain. They simply wanted to live happier lives, if not of their own then at least of their children.

A typical Korean family in a kolkhoz after 1956. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Young Nikolay Ten with his siblings. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Early Memories

Nikolay saw real bread for the first time in his life at the age of five. Before that his mother had always used compressed grass to “bake” bread of some kind. It was so heavy to digest that children often suffered from severe stomach aches, especially after eating a lot of it.

In the early 1950s they lived with constant food shortages: little Nikolay, his mother and two elder sisters (his third sister would be born ten years later).

“We had a cow, some chickens, and a pig. My dad had left to study at a pedagogical university, and my mother was left alone with three little children, taking care of our house and the animals.”

This is why she finally stopped working in the kolkhoz – there always was plenty of work at home. During the nights and after everyone had left to sleep, she was still awake, secretly sewing clothes, to be sold later to neighbors. All forms of private entrepreneurship were strictly prohibited back then by the Soviet state. Therefore, Galina’s nighttime work had to stay hidden.

Galina Lee with her husband Konstantin Ten and children. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

“I was always playing outside the house as a little boy,” Nikolay remembers very emotionally, “and if I suddenly saw anyone around who didn’t look Korean, I would immediately run back to my mother and shout ‘Inspector is coming, inspector is coming!'”

Galina worked so hard during the day and in her nighttime shifts of sewing, that eventually it took a physical toll. “I had to start drinking cow milk way too early, because my mom was so stressed during the day and so tired of sleepless nights that there was no more milk left in her to feed me…”

Eventually, Galina was able to find a legal job in a state-owned tailor shop. Konstantin came back after finishing at university and became a math teacher at a local school. He worked as a math teacher for the rest of his life. They both were awarded with medals for their very hard lifelong labor.

Nikolay’s parents’ medals and state awards. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Next week we’ll wrap up the series with the story of Fedor Lee and also the fate of those who heeded the call to return to North Korea in the 1950s.

Acknowledgments: Part of the archival photography presented in this report on the Koreans in Soviet Uzbekistan, including several photographs by a distinguished Uzbek Korean photographer Viktor An, were sourced from www.koryo-saram.ru and used in this multimedia project with the permission of the blog’s owner Vladislav Khan.

---

Lost and Found in Uzbekistan: The Korean Story, Part 3

In the final chapters, the mystery of Fedor Lee is solved and some of the Uzbek Koreans return to North Korea.

By Victoria Kim

June 21, 2016

A festive postcard sent by little Lenya from the newly established DPRK back to Uzbekistan.Credit: Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

This is the third in a three-part presentation of Victoria Kim’s multimedia report, created in memory of her Korean grandfather Kim Da Gir (1930-2007), which details the history and personal narratives of ethnic Koreans in Uzbekistan. It was originally published in November 2015 and is republished here with kind permission. Read part one and part two.

***

Fedor Lee in the Soviet army. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Fedor Lee

There is one memory that is especially painful for Nikolay. It is the memory of a very dark night back at home. He was still a very small child.

As a 3-year old, Nikolay could vividly remember everything around him. That night he was peacefully sleeping in his bed, when adult voices suddenly woke him up. Nikolay walked into the living room and saw a crying Korean stranger. He was telling something to Nikolay’s parents who were also crying while listening to him.

Nikolay still cries himself like a small child, telling me this story 60 years later.

When his mother came to Soviet Uzbekistan as a deportee in the cattle train together with her parents and sisters, her brother was left behind. He was only 21 and served in the Soviet military back in the Far East.

He was positioned in Kraskino town and separated from the rest of his family who lived in Crabs. When Stalin’s order for the deportation of Koreans came, he discovered that his whole family had been shipped to Uzbekistan on a train only very shortly before his own arrest.

As a soldier, Fedor Lee was under an even higher level of suspicion and scrutiny than the rest of the Koreans. According to the official version, he was accused by his neighbors of being a Japanese spy, declared a traitor and an enemy of the Soviet state.

Fedor was condemned to ten years of forced labor in the Siberian gulag in Komi Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. He did not last even through the first half of his imprisonment.

The Korean stranger who visited Nikolay’s family 15 years later was his uncle’s fellow prisoner in the gulag. He told Nikolay’s parents that Koreans were treated the worst by the guards among gulag prisoners, and only a couple of them survived the horrors of their imprisonment.

Every day they were sent to cut lumber deep in the Siberian woods, in spite of freezing temperatures, lack of warm clothes and malnutrition. Fedor badly injured his legs while cutting a tree, and in the cold weather developed gangrene. Even though he was unable to walk, Fedor’s comrade would remember, they still had to take him out to their working station, where he would cut branches from fallen trees.

After he got so weak that he could not work any longer, the prison guards shot him. It happened in the early 1940s, and nobody really knew where his body had been buried.

“My family was taken on a train all the way to Uzbekistan,” Fedor told his comrade shortly before dying. “If you manage to survive through all of this, please promise me you would go and find them… Please promise you would tell them my story, everything they have done to me.”

The comrade, whose name we will never know, fulfilled his promise to Fedor. He found Fedor’s family and came all the way to Uzbekistan to tell them everything that had happened.

Alexey’s first son Leonid – one of the only photographic memories left of Alexey Ten. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Alexey Ten

It seems that in the lives of some there can never be too much suffering.

The lives of two generations–Nikolay’s grandparents and parents–bear clear signs of two waves of repressions against the ethnic Koreans and political prisoners of the Soviet state between the early 1930s and late 1950s.

There is, however, one more story left to tell. One more wave of repressions left to recount. This is one of – if not the most – secretive part of history in the lives of Soviet Koreans. This is the story not so many people happen to know about.

A secretive wave of repressions against Soviet Koreans in the DPRK (from the materials at the US Library of Congress)

Alexey Ten came to Uzbekistan on the same cattle train, together with his brother and Nikolay’s father Konstantin. Together they worked in the swampland and later rice fields, and then Alexey went to study in the Chirchiq military academy near Tashkent, where in the early 1950s he was approached with an unexpected order by his higher military command.

The special request came from the young Comrade Kim Il-sung, picked by Joseph Stalin in the indirect stand-off between the Soviet Union and United States over the Korean peninsula, to lead the North Korean communists. In the early 1950s, this stand-off led to the Korean War, which became known eventually in the West as the Forgotten War.

Back then, young and energetic Comrade Kim Il-sung sent a direct plea of help to all brotherly Soviet Koreans, asking those in the military ranks to fight the Korean War shoulder to shoulder with him in order to liberate the Korean peninsula from imperialist aggressors.

Many Uzbek Koreans from the Chirchiq military academy, together with other Central Asian Koreans, went and fought the Korean War shoulder to shoulder with Kim Il-sung, helping him to liberate North Korea and establish the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK).

Most of these Koreans stayed in North Korea afterwards as war heroes and Kim Il-sung’s closest friends and allies. They became generals, marshals, and admirals in the DPRK’s newly built military apparatus. Alexey Ten was among them – he became a general and the DPRK’s deputy minister of defense.

Alexey’s son Leonid or little Lenya. Courtesy of Victoria Ki.

Recognition at Last

Konstantin, Nikolay’s father, must have finally felt very happy for his brother – at last, he was in a very high and powerful position in a country that seemed to highly appreciate him. Earlier and while still living in Uzbekistan, Alexey Ten got married and had his first son Leonid, whom all of his brother’s family felt especially close to.

.

Later, after Alexey had fought together with Kim Il-sung in the Korean War , his family lived in North Korea. Alexey’s wife got badly ill with appendicitis and was operated on across the border from North Korea in the Chinese city of Harbin, but didn’t survive. Alexey eventually remarried a North Korean woman and had several more children with her; meanwhile his first son Leonid kept living with them in North Korea.

After the direct request from the Comrade Kim Il-sung, he and many other Uzbek Korean war heroes surrendered their Soviet citizenship in exchange for DPRK citizenship. The DPRK seemed to euphorically claim them back.

During this time, there was a unique exchange of letters going on between Upper Chirchiq in Uzbekistan and Pyongyang in North Korea, with the help of the North Korean Embassy in Moscow.

Konstantin, Nikolay’s father, would write to his brother Alexey or his nephew Leonid, always in Korean, and send his letters to the DPRK’s Moscow embassy, which would then pass them directly to General Chon Il Bang (the name Alexey Ten took) in Pyongyang, and vice versa.

Nikolay managed to keep some of the remaining letters, together with the photos of his cousin little Lenya.

Little Lenya’s postcard from North Korea to his uncle Konstantin. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

A colorful and happy postcard from Pyongyang signed with a trembling hand of the little child in broken Russian, wishing his cousins the best of luck and plenty of health. The lines in Korean from both brothers and little Lenya, who would always write all first names and some particular words in Russian, as if trying not to forget his mother language.

Konstantin’s letter to his brother Alexey in North Korea. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

The signature of the North Korean ambassador in Moscow, stating that he had indeed passed the letters between the recipients.

Those invisible ties that linked the Uzbek Koreans back to North Korea weren’t to last long. Nor was their euphoric success in the DPRK, a historical motherland they were so happy and proud to help rebuild, to be anything but brief.

Konstantin’s letter to Pyongyang, returned with a stamp “Incomplete address.” Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Recipient Unknown

In 1953, upon the death of Joseph Stalin and the demolition of his personality cult as contradicting to the true principles of Leninism, the relationship between North Korea and the Soviet Union started to deteriorate.

Kim Il-sung, who adopted the system of adoration and political reprisals from his own beloved Great Leader, felt vulnerable after Stalin’s defamation in the USSR and started suspecting the new Soviet command of plotting to destroy him in a direct coup d’etat.

Among the first to blame for the same old sins – political and military treason, espionage, and animosity to the DPRK – were the same Soviet Koreans who again and again found themselves between the wheels of ruthless state machinery bound to destroy them.

Purges began one by one against Kim Il-sung’s closest friends, former fellows, and allies. The DPRK’s highest military apparatus consisting mostly of Soviet Korean ministers, deputy ministers, generals, marshals, and admirals was soon and completely eradicated.

It looked like Kim Il-sung was trying to change the past and make it seem as if the years between the 1940s and 1960s had never existed. He did everything possible to wipe out the entire memory of the traitors who had given him and their historical motherland everything, up to their own lives.

Suddenly, Konstantin’s letters started returning from the Moscow-based North Korean embassy with a weird stamp: “Recipient unknown.”

Recipient unknown, Konstantin’s letter returned from North Korea. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Alexey’s postal address simply ceased to exist. Nobody could explain anything. Konstantin kept sending letters, and the letters kept coming back with the same postal stamp, “recipient unknown.” This lasted until Konstantin, exhausted and anguished, managed to talk directly to the North Korean ambassador in Moscow, who finally explained everything.

“Don’t look for your brother any longer. Stop sending him those letters. There is no way to find him or his family now. They have been purged as traitors, spies, and enemies of the state, and we know nothing about them at this point. And, probably, we will never know.”

Galina Lee and her grandchildren. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Post Scriptum

How many cycles of repression can one survive? How many tears can one cry? How many family members can one lose? And the most important question – what for and whose fault is it that such atrocities keep happening?

The Soviet Koreans, Uzbek Koreans, Koreans kept spinning again and again, crushed between the wheels of history, betrayed and dishonored again and again by a foreign motherland. How many motherlands can one lose and how many of them can one get?

Lenin medal and certificate book. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

And what is it worth, after all, when at the end the only thing you are bound to be is homeless, forgotten, and dishonored? Nikolay’s parents could never answer those questions. Have they even asked them?

Nikolay answers my question this time. “Have they ever blamed Joseph Stalin or the Soviet state for what it had done to them? Maybe, they did. Probably so. I don’t really know, because they were never free to talk about it, even with us. I don’t blame anyone any longer. I simply hope such atrocities will never happen again.”

Galina Lee with her children – Nikolay Ten and his three sisters. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Part of the archival photography presented in this report on the Koreans in Soviet Uzbekistan, including several photographs by a distinguished Uzbek Korean photographer Viktor An, were sourced from www.koryo-saram.ru and used in this multimedia project with the permission of the blog’s owner Vladislav Khan.

---

No comments:

Post a Comment