https://archive.org/details/politicideariels00kimm_0/page/n7/mode/2up

Kindle

$21.15

Politicide: Ariel Sharon’s War Against the Palestinians Kindle Edition

by Baruch Kimmerling (Author) Format: Kindle Edition

4.6 4.6 out of 5 stars 4 ratings

Ariel Sharon is one of the most experienced, shrewd and frightening leaders of the new millennium. Despite being found both directly and indirectly responsible for acts considered war crimes under international law, he became Prime Minister of Israel, a political victory he won by provoking the Palestinians into a new uprising, the second intifada.

From the beginning of his career Sharon was regarded as the most brutal, deceitful and unrestrained of all the Israeli generals and politicians. A man of monstrous vision, his attempts to destroy the Palestinian people have included the proposal to make Jordan the Palestinian state and the now infamous invasion of Lebanon in 1982, which resulted in the Shabra and Shatila massacres.

Baruch Kimmerling's new book describes Sharon's quest to reshape the whole geopolitical landscape of the Middle East. He describes how Sharon is committed to politicide, the destruction of the Palestinian political identity, and how he has won the support of powerful elements within Israeli society and the present American administration in order to achieve this. At this time of crisis Kimmerling exposes the brutality of Sharon and his junta's "solutions" and constructs a devastating indictment of a man whose cruelty and ruthlessness have resulted in widespread and indiscriminate slaughter.

Product description

Review

Baruch Kimmerling, a Jew with a biblical conscience, gives us in Politicide not only a devastating critique of Ariel Sharon but an acutely perceived history of the Israeli occupation of Palestine. He writes with care and with passion. It is a book both scholarly and heartfelt and I hope it will be widely read. -- Howard Zinn

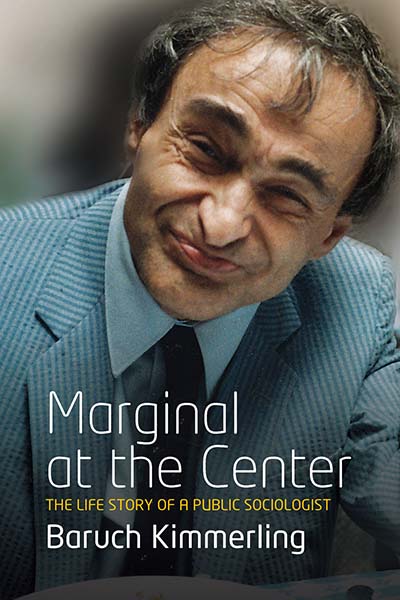

About the Author

Baruch Kimmerling was Distinguished Research Professor at the Department of Sociology at the University of Toronto and George S. Wise Professor of Sociology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He published numerous books and articles on Israel and Palestine including, with Joel S. Migdal, a revised and enlarged edition of Palestinians: The Making of a People. He died in 2007.

==

Top reviews from other countries

Michael Hoffman

5.0 out of 5 stars A Devastating Expose of Ariel SharonReviewed in the United States on 12 June 2003

Verified Purchase

Prof. Baruch Kimmerling's new book about the checkered career, heinous war crimes and diabolical treachery of Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon is of such critical importance to understanding the expolsive Middle East crisis, that one would think it would make the cover of Newsweek, and be the subject of discussion and debate from the New York Times to the CBS Nightly News. Needless to say, publicity for Kimmerling's expose has been tightly suppressed by the Establishment media, who have a vested interest in portraying the Butcher of Beirut as an honorable, if hawkish warrior and Zionist "patriot."

The truth, according to Kimmerling's formidable research, is very different. The bill of indictment is eye-popping. Sharon is a Nazi, a racist and an assassin intent on imposing a defacto concentration camp on the Palestinians. Extreme? Yes, but Sharon is the epitome of extremism.The bloody wreckage of Palestinian AND Israeli lives is effectively the basis for "Politicide."

Put aside the System-approved fantasies by Bernard Lewis, Dore Gold and Steve Emerson. Instead, study this courageous and revealing work from a writer who embodies a voice of conscience and dissent against what is done in the name of the Jewish people to the hapless natives of Palestine.

The fact that this book is being denied publicity by the corporate media is one hint of its power. The System seeks to protect at all costs the reigning paradigm. In "Politicide," Kimmerling indicts mass murderer Sharon, and he does so without polemics, with a cool recitation of facts.

"Politicide" is fallible and there are a couple of errors: the author upholds the official Israeli line on the Jenin massacre and the attack on the Church of the Nativity; and there is one noteworthy omission: all mention of Baruch Goldstein's 1994 massacre of 40 Palestinians as the flash point that initiated suicide bombings, beginning in April of that year.

With those caveats noted, this book is nonetheless a huge embarrassment for the legion of Sharon partisans in the American media and US government ,and they are doing their worst to keep "Politicide" in the deep freeze. But if Kimmerling's work gains a wide American readership, I predict that Sharon's usefulness to the Cryptocracy will be finished and many lives may be saved.

Read less

43 people found this helpfulReport

E. Rodin MD

5.0 out of 5 stars Must read for American public and politiciansReviewed in the United States on 8 July 2006

Verified Purchase

Professor Kimmerling's book is an important contribution to the understanding of the Israeli-Palestinian war and should be read by everyone who is concerned about the future of our country. America's Middle East policy is at this time not evenhanded but clearly favors Israel's wishes over those of other countries in the region. Since Kimmerling documents the oppressive policies of Israel toward its conquered Palestinian population Americans need to read this book which presents the proverbial other side of the coin.

This is especially topical now when guns are blazing again in Gaza and Israel uses the pretext of freeing a kidnapped soldier to punish the Palestinian people for democratically electing a Hamas led government. The current situation clearly proves Kimmerling's point, that a viable Palestinian state will not be tolerated by Israel's government.

The book discusses the "pre-emptive" 1967 war which led to the Yom Kippur war and the ill advised invasion of Lebanon for which Sharon was mainly responsible. He was also the main architect of the settlement program in the occupied territories which has now become a millstone around the neck not only of Israelis and Palestinians but also Americans because neither of the parties can see a just solution to this increasingly vexing problem. Kimmerling's excerpts from "Machsomwatch," which detail the conditions Palestinians are forced to live under are especially poignant.

When one reads this book it becomes clear why the rest of the world does not trust America at this time and only when America will begin to support, instead of vetoing, resolutions in the UN which demand an end to Israel's current practices will there be a semblance of hope for peace.

Read less

8 people found this helpfulReport

See more reviews

.png)

.png)

.png)