Park Statue Politics: World War II Comfort Women Memorials in the United States

Thomas J. Ward and William D. Lay

5,532 Downloads

Free PDF

Amazon (UK, US, DE, FR, CA)

And all good book stores

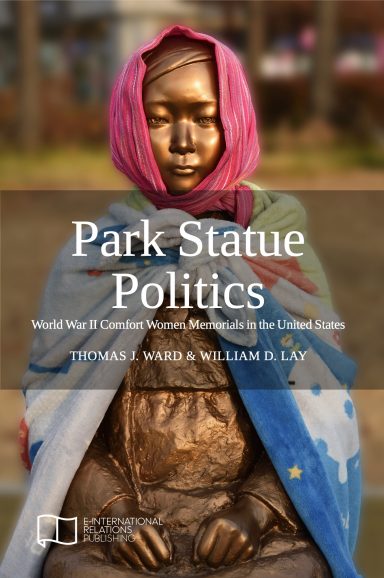

Numerous academics have researched Japan’s comfort women system that, for decades, forced innocents into sexual slavery. Since 2010 a campaign has been in place to proliferate comfort women memorials in the US. These memorials now span from New York to California and from Texas to Michigan. They recount only the Korean version of this history, which this text finds incomplete. They do not mention that, immediately following World War II, American soldiers also frequented Japan’s comfort women stations. The Korean narrative also ignores the significant role that Koreans played in recruiting women and girls into the system. Intentionally or not, comfort women memorials in the United States promote a political agenda rather than transparency, accountability and reconciliation. This book explains, critiques, and expands on the competing state and civil society narratives regarding the dozen memorials erected in the United States since 2010 to honor female victims of the comfort women system established and maintained by the Japanese military from 1937 to 1945.

Find out more about E-IR’s range of open access books

288.1K

Tokyo 2020's Mori to quit, end controversy – sources

About the authors

Thomas J. Ward is Distinguished Dean Emeritus of the University of Bridgeport’s College of Public and International Affairs. An honors graduate of the Sorbonne and a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Notre Dame, he did his doctoral studies in Political Economy and International Education at the Catholic Institute of Paris and De La Salle University in the Philippines. He teaches graduate courses in International Conflict and Negotiation and Political and Economic Integration. A former Fulbright scholar, he has lectured at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing, and has been a Visiting Research Fellow at Academic Sinica in Taipei. His research on the comfort women issue has been published in East Asia and Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus.

William D. Lay is Director of the School of Public and International Affairs, and Chair, at the University of Bridgeport. He teaches graduate and undergraduate courses in international public law, international humanitarian law, US constitutional and criminal law, and human security. Born in Tokyo, he has traveled extensively in Asia and the Asia Pacific region. He was a Kent Scholar throughout his years at Columbia Law School, and was Senior Editor of the Columbia Law Review. He clerked at the New York Court of Appeals for Judge Joseph Bellacosa, a recognized authority on New York criminal procedure, and practiced law for 12 years with the Fried Frank and Skadden Arps firms in New York City before joining the UB faculty. His articles on East Asia have appeared in East Asia and the Harvard Asia Quarterly.

Table of contents

INTRODUCTION

LOCAL POLITICS: THE PROS AND CONS OF PARK STATUES

THE ORIGINS AND IMPLEMENTATION OF THE COMFORT WOMEN SYSTEM

STEPS TOWARD REDRESS FOR THE COMFORT WOMEN

KEY MILEPOSTS AND ACTORS IN EFFORTS TO SETTLE THE ONGOING COMFORT WOMEN IMPASSE

KOREAN CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS: ACCOMPLISHMENTS AND EXPECTATIONS

OPPOSITION TO COMFORT WOMEN MEMORIALS IN THE UNITED STATES

THE UNUSUAL CASE OF TAIWAN

STATUE POLITICS VS. EAST ASIAN SECURITY: THE GROWING ROLE OF CHINA AND CHINESE-AMERICAN CIVIL SOCIETY

INCONSISTENCIES IN THE KOREAN NARRATIVE

THE COMFORT WOMEN CONTROVERSY IN THE AMERICAN PUBLIC SQUARE

THE IMPLICATIONS OF ESTABLISHING A COMFORT WOMEN MEMORIAL IN THE UNITED STATES OR EUROPE

CLOSING THOUGHTS

Dedication

In the mid-1930s, the government of Japan established a government- controlled network of brothels, referred to as “ianjo” or comfort stations, based on a massive Japanese private prostitution network in place since the emergence of Japan as a colonial power in the late nineteenth century. The ianjo system involved the deployment of tens of thousands of indentured Japanese sex workers across Northern Asia. As Japan prepared for war in the late 1930s, its military decided against continuing to recruit Japanese women for this purpose. The government replaced them largely with innocent Korean women and girls who joined the military because, in most cases, they had been deceptively recruited based on promises of a bright future with education and respectable, gainful employment. Instead these women became the exploited sex prisoners of the Japanese Army and the collaborators who had misled them into an unending nightmare of terror and rape.

This book is dedicated to the tens of thousands of women and girls who endured such deception only to face daily, multiple sexual violations by the Japanese military during World War II. Let us also remember the empty, ruined lives that surviving victims faced when they returned home after the war. They became marginalized from society because they had committed the “crime” of being raped. Sadly, the role played by Korean, Chinese, and Taiwanese collaborators in the deceptive recruitment of women and girls for Japan’s comfort women system must also be told. Just as the Croat, Serb, and Romanian nationals who oversaw Hitler’s concentration camps did not escape judgment because they too were “victims.” The crimes of the comfort system collaborators should not be concealed when the comfort women’s story is told.

We should not forget that the American military also had a role in all of this. They patronized the comfort women system during the first year after the war. After that, for 72 years until today, American GIs have patronized the hundreds of thousands of women and girls trapped in the camp towns around U.S. bases in Japan, Korea, and the Philippines. Like the WWII comfort women, many of these women’s lives have also been destroyed. Nor can we forget that today, North Korean women escape every day across the border into China. To repay the “debt” for their “freedom,” these women will be sold into a forced marriage or to a brothel in China. Many will face the same personal shock and terror that women and girls endured three-quarters of a century ago under Japan’s military during the Pacific War. Human trafficking extends far beyond Asia. By properly telling the story of the comfort women and properly identifying all responsible parties, we believe that we can best contribute to a future world where all women will experience that personal dignity, respect, and genuine love that the comfort women could never know.

REVIEWS

A much better book than nearly anything else available from American university researchers on the subject.... Park Statue Politics, it is hoped, will be the beginning of a long-overdue reassessment of the history that underlies the historiography and the politics that distort our understanding of the past.

— Jason Morgan, Reitaku University

---

4 global ratings

5 star

53%

4 star 0% (0%)

0%

3 star

24%

2 star 0% (0%)

0%

1 star

23%

Park Statue Politics: World War II Comfort Women Memorials in the United States

Park Statue Politics: World War II Comfort Women Memorials in the United States

byThomas J. Ward

Write a review

How are ratings calculated?

See All Buying Options

Add to Wish List

Search customer reviews

Search

SORT BY

Top reviews

Top reviews

FILTER BY

All reviewers

All reviewers

All stars

All stars

Text, image, video

Text, image, video

4 global ratings | 4 global reviews

From the United States

TPI

3.0 out of 5 stars A much-needed analysis with strengths and weaknesses

---

Reviewed in the United States on May 5, 2019

Authors Ward and Lay attempt to present a controversial issue in a balanced way.

A laudable aspect of this book is that it presents facts that Korean activists have hidden in order to evoke outrage against Japan and Japanese. The section "Inconsistencies in the Korean Narrative" highlights perhaps the most important take-home message: the Korean narrative that has spread globally is inaccurate, incomplete, and misleading. Justice-minded people must be cognizant of this crucial point, and bring it to light.

The book has shortcomings in that it contains numerous factual inaccuracies, echoes at times the evocative tone of Korean activists, and neglects to cite salient historical records, all of which creates bias.

Scholarly analysis should avoid the use of bias-inducing, ambiguous, or inflammatory words, except to point them out. The very first sentence of the Abstract states that the comfort women system existed for "decades," leaving the connotation of at least 20 or more years. Only later do we read "1937 to 1945" ─ a period of less than ten years. The provocative term "slavery" also appears in the first sentence, leading American readers to think of America's institution of slavery. Only later do we learn that the systems differed substantially, e.g., Korean comfort women could return home when their contracts were fulfilled; parents of the women and/or the women themselves were paid. On p. viii, it states that Korean comfort women "joined the military" and that the "Japanese Army...misled them." Korean women typically worked at brothels owned and operated by civilians (often Korean) who owned the contracts ─ thus, the women were "indentured" to and worked for these civilian owners, not the military. The military in general did not recruit or mislead Korean women into becoming comfort women: civilian (often Korean) brokers, recruiters, and brothel proprietors did that. The women's treatment varied, depending on the individual civilian operator. The military regulated the brothels (for the protection of both the soldiers and the women) and regrettably upheld the contracts that the parents had agreed to. Many other imprecise statements are present throughout the book.

A large volume of primary source documents/historical records from that time period (written in Korean and Japanese) have been overlooked. Several times, allegations and opinions are stated as facts. The book omits mentioning that the testimonials of some former comfort women ─ after being recruited by activists ─ have changed over time to misrepresent Japanese military conduct, so as to evoke outrage against Japan. As oral testimonials carry great weight, this fact must be made known.

Another point that is mentioned in the book and deserves stronger emphasis is that socioeconomic inequality (poverty and patriarchal social structure) were key underlying factors contributing to this tragedy, where desperately-poor parents sold their daughters' services in order to survive, or women with few opportunities joined in hope of a better life (possibly after being misled about the type of job). Although brokers often misrepresented the nature of the work, it would be naïve to believe that many or most fathers did not know the likely fate of their daughters, given that thousands of Korean comfort women served. Poverty forced fathers to sell their daughters. By placing blame solely on Japan, activists destroy a teaching opportunity to educate the world that poverty and gender inequality helped set the stage for this tragic event. These misrepresentations only hurt disadvantaged girls and women of today.

Though not mentioned in the book, in many ways the comfort women movement has more in common with hate-based movements than a movement seeking justice, when one recognizes that Korean activists (1) ignore crucial facts; (2) show hypocrisy by hiding the misconduct and war crimes committed by S. Korean forces during the Vietnam War; (3) work relentlessly to vilify Japan through half-truths; (4) dismiss the vitally-important (from Japan's perspective) 1965 Treaty and Agreement (whereby Japan paid S. Korea today's equivalent of billions of dollars with the mutual understanding that all claims between the nations and their peoples were settled, and that it became the responsibility of the S. Korean government to compensate Korean citizens); and (5) decry Japan's every attempt to apologize and atone (subjectively claiming they are insincere or not official), while not insisting S. Korea give an official apology, acknowledgement, and atonement for crimes committed by S. Korean troops.

For a less anti-Japan perspective, an invaluable resource is "Comfort Women and Sex in the Battle Zone" (2018) by Prof. Ikuhiko Hata, a Japanese historian who has conducted extensive research on this topic.

Authors Ward and Lay deserve credit for presenting facts that have been hidden by Korean activists. Hopefully, for scholarly integrity, the authors will update their work, correcting the inaccuracies and expounding even more on the findings of researchers such as Prof. Hata, Prof. Yu-ha Park, Prof. Tsutomu Nishioka, Prof. Byeong-jik An, Prof. Young-hoon Lee, and investigators such as American Lt. Col. (Ret.) Archie Miyamoto, whose book "Wartime Military Records on Comfort Women" (2018) is available on Amazon. Their research challenges much of the mainstream narrative, especially the veracity of some testimonials.

How can there be justice based on half-truths?

8 people found this helpful

--

Alain C. Morgenthaler

5.0 out of 5 stars More than could be expected

Reviewed in the United States on May 1, 2019

This compact volume achieves much more than could be expected from the latest in a long series of publications that include the misleadingly harmless sounding “comfort women” in their titles. There are at least two reasons for this.

Park Statue Politics does not primarily seek to relitigate the issue of comfort women – young women from Korea, China, Taiwan, the Philippines and even Japan, who were forced into providing the most traumatizing and dehumanizing form of “service” to Japanese troops during and before World War II. Its focus is on the recent phenomenon of memorials appearing across the USA. These memorials, in the form statues (see the book cover), duplicate those placed in Korea near the Japanese embassy and consulates as a form of protest. They bring the issue onto the international scene, in front of a public that has little knowledge of the historical background. The authors analyze the back and forth (involving Korean activists, Japanese representatives, and mayors of US towns) over the appropriateness of displaying such statues on US soil and the one-sided message they send. Their skepticism on this point may anger many Koreans, but their voice deserves to be heard.

In my opinion, here is why, and that is the second reason: in this politically charged debate, academics not only affect public opinion – they are also affected by it. After all, they are part of the public themselves, though they should be expected to remain dispassionate and objective. To a European like myself, the degree of hostility between Japan and Korea, two close allies, some 75 years after the end of hostilities, can be puzzling. It can be explained by the unique history that links the two countries. Unfortunately, many actors (including some academics) first and foremost aim at demonstrating the correctness of their own national narrative. Ward and Lay base their enterprise on the assumption that conflict transformation can hardly be achieved in this way. They have conducted serious and comprehensive research that will displease hardliners on both sides – a good sign. For this reason alone, their findings largely deserve inclusion in the discussion on how Americans respond to this tragic chapter of history.

One person found this helpful

--

Ledocteur

5.0 out of 5 stars A Major Contribution to the Field

Reviewed in the United States on June 26, 2020

This text challenges the extant Korean and Japanese narratives (on the comfort women) that are prevalent in the United States. It looks at the role that the United States played in both deciding not to prosecute the guilty parties after World War II and in the American military usage of the comfort women system in the seven months after the end of the War. The text is critical of American politicians for failing to take the time to understand the "whole picture," including the complicity of the United States in these events.

In a politically sloppy, self-serving manner, US politicians seem to have forgotten the internment camps that the US built during WWII to confine native-born US citizens because of their Japanese ethnicity; they seem to have forgotten the young innocents who died slow, painful deaths after the attack on Hiroshima; they seen to have forgotten the young people of Japanese heritage in Latin America who were kidnapped during WWII by American military forces to barter for US troops held by Japan. US politicians have approved monuments that dismiss that history of sorrow. The monuments only denounce Japan and ignore America's complicity in this tragic chapter of history. That such monuments appear in Korea is fully understandable. That such monuments are built in America, relying only on the Korean narrative is not. Read the book!

--

DeepThinkingReader

1.0 out of 5 stars Quite disappointing and could have been much better

Reviewed in the United States on April 24, 2019

Although the two authors seem to value the work by C. Sarah Soh who published a must-read tome in 2008, The Comfort Women, they contradict her findings in a number of ways. Soh’s book distinguishes a) the criminal cases such as Semarang in the Dutch East Indies (present Indonesia) and the violent acts by the Japanese military in the Philippines from the b) Korean comfort women experience through her personal interviews and research. However, this book conflates the two by, as an example, making the assertion that military doctors and medical workers frequently raped the women during physical exams by citing statements by Jan Ruff O’Herne at the U.S. House of Representatives hearing in February 2007. Ms. Ruff O’Herne was a victim of rape and violence in the Dutch East Indies, and such sloppy conflation can be found throughout the book to promote the popular narrative of comfort women having been sexual slavery victims of Imperial Japan’s “rape centers.”

Other factual errors, whether they were deliberate or not, can be found frequently as well. For instance, the authors claim that Kim Hak-sun was the first former comfort woman to go public in 1991. The truth is that a Japanese by the name of Yoshie Mihara was the first ever to come out and discuss her experience in 1986, not a Korean. This fact is clearly stated in Sarah Soh’s 382-page book, so one can assume that it was omitted because the voice of a Japanese does not matter (or shouldn’t be heard) in order to advance the narrative.

=============

Published 1 year ago

on September 15, 2019

By Jason Morgan, Reitaku University

There has been a troubling lack of understanding of the comfort women issue. Indeed, given the refusal in many quarters to see the comfort women in any light other than the mythological, it is a very welcome development to see two scholars attempt to understand comfort women “park statue politics” from a fresh, non-ideological perspective.

This is the self-imposed remit of Thomas J. Ward and William D. Lay’s book, Park Statue Politics: World War II Comfort Women Memorials in the United States, namely: to clear away the historiographical static and present an easy-to-understand guide that city leaders in America can use when deciding whether to approve comfort women statues in a given municipality.

Unfortunately, Ward and Lay fail to break free of the mytho-historiographical fog surrounding the issue. However, their book still serves as a guidepost for understanding why the comfort women ideology has gained such a stronghold on the American imagination.

Ward and Lay — both professors at the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut — make an attempt to provide context for the comfort women issue before wading into full-blown “statue politics” in the last third of the book. But already, in the beginning, we can see that obfuscating elements pervade the Ward and Lay volume.

The ideological filter is in effect from page one, and the blinders of the comfort women narrative — the mytho-historiography voiced by activists and echoed throughout American academia and the American press — very clearly prevent Ward and Lay from digging down into and exposing the real historical humus beneath the ideological overgrowth.

Early Trouble

A balanced scholarly tone, analysis, and proper citations are lacking from the beginning.

For example, the very first footnote on the very first page is from the Korea Times, an English-language newspaper based in Seoul. The next two footnotes are from the Japan Times, which until very recently hewed to essentially the same editorial (activist-centric) line as the New York Times. The fourth footnote is from the English-language edition of another Korean newspaper, the heavily left-leaning Hankyoreh, and the fifth and sixth footnotes are from UNESCO, which the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has long been using as a platform for attacking Japan.

Left-wing newspapers and U.N. documents, all apparently in English. This is hardly the stuff of rigid, or original, scholarship in a contentious topic with roots very deep in the East Asian past.

From the outset, then, the tone of the book biases the reader. Ward and Lay are triply trapped: first, by an apparent unwillingness to meticulously consult original historical documents; second, by an apparent inability to read pertinent languages (most relevant records are in Japanese and Korean); and, third, by an apparent reluctance to seek out voices from beyond the academic-journalistic complex which was instrumental in creating the comfort women mytho-historiography in the first place.

There is Also Good News

To be fair, Ward and Lay do stretch much farther outside the usual academic circles than almost any of their American peers. They are to be very much credited, for instance, for making good use of the research of C. Sarah Soh, who has done very important work in contextualizing the comfort women issue within the larger East Asian, and even world, milieu.

Ward and Lay also provide a space for Koichi Mera, famous for his dissenting views on the comfort women issue in the United States, to have a say. One gets the overall impression from the volume that they sincerely tried to find ways to balance the relentless homogeneity of the U.S. academy and media with information not necessarily toes-down on the party line.

If only they had tried harder. Koichi Mera has certainly been vocal in his opposition to “park statue politics” in the United States, but there are careful historians who have done much more, and much better, actual research on the comfort women. To be sure, many of these historians write in Korean and Japanese — Park Yuha and Tsutomu Nishioka come immediately to mind.

But doyen of modern Japanese history Ikuhiko Hata’s definitive book on the comfort women issue became available in English a year before this short volume of Ward and Lay’s came out. The first version in Japanese had been published in 1999. How did the two Connecticut professors miss it?

Further, other Korean academicians have spoken out against the false historiography, but I looked through the book in vain for leading lights, such as Young-hoon Lee, Byeong-jik An, Joseph Yi, and many others.

Same Recycled Errors

Objective analysis requires interrogating the validity of source material. So it is disappointing that Ward and Lay spent page after page virtually reproducing passages from Yuki Tanaka and George Hicks, whose books on the comfort women are riddled with outright falsehoods. On page 15, for example, Ward and Lay cite Hicks in asserting that Japanese troops “executed the Korean comfort women when they retreated from losing battles with Allied forces,” although there is not a shred of corroborated evidence that this happened.

On the same page, Ward and Lay again cite Hicks in asserting that comfort women “serviced troops along the Japanese Imperial Army’s frontlines.” It takes very little imagination or common sense to realize that setting up brothels next to foxholes would have been either suicidal or farcical, or both — to put it bluntly, how would men hunkering down under withering mortar and machine gun fire find time for sex, and how would they manage to defend unarmed women if they could barely hold their own line in the dirt?

This is where scholarly due diligence would have come in very handy. The questionable veracity of Hicks’s book should have been clear, as Hicks clearly acknowledges that most of his book was based on the findings of one woman of Korean descent living in Japan who worked with activists. Further, Hicks fails to explicitly specify (that is, page number, author, etc.) the sources for many of the claims made in his book — a red flag for every serious scholar.

Even More Serious Problems Await

Because Ward and Lay have made little effort, it seems, to question the anecdotal claims about and by the comfort women in the sources they cite, they can hardly be held responsible for repeating others’ wild untruths. However, given the gravity of this issue, Ward and Lay really should have done more than just a modicum of homework when investigating the present state of “park statue politics,” which is the title of their book and the overall theme of their investigation.

To give just one example, Ward and Lay assert that “Michael Honda, the unflagging U.S. Congressional proponent of a more assertive Japanese apology, was named ‘Honorary Curator’ of the [WWII Pacific War] museum [in Chinatown in San Francisco].” This uninterrogated sentence fairly staggers the mind. First, he is known everywhere as “Mike” Honda, not “Michael.” Moreover, Mike Honda was long under investigation by a House ethics committee for allegations that he shunted taxpayer money into his own campaign coffers, the kind of corruption central to “park statue politics.”

But it gets worse. Honda was later photographed — in South Korea — with Russell Lowe, who was United States Senator Dianne Feinstein’s driver and assistant for 20 years. Lowe was fired after the Federal Bureau of Investigation discovered that he had been working as a spy for the People’s Republic of China while he was in the employ of the senator. Undeterred, Lowe immediately began working at the Comfort Women Justice Coalition, which was the organization instrumental in bringing the comfort women statue to San Francisco.

The public face of that drive was provided by Lillian Sing and Julie Tang, two judges who retired in order to carry out their anti-Japan propaganda full-time.

The Final Word

There is one more serious flaw in the “park statue politics” book. In their work, Ward and Lay give scant mention of the dismay, frustration, and pain felt by those Japanese Americans and Japanese residing in the U.S. who know comfort women history.

These Japanese Americans and Japanese in America, who hold visible positions, are fearful of speaking out, lest they be labeled “denier,” “apologist,” “misogynist,” or, worse, and possibly suffer retaliation. This is the human cost of an inaccurate historiography, spread to evoke outrage and hatred toward an entire nation and ethnic group.

Park Statue Politics is, unfortunately, an unwitting testament to the power of the comfort women myth in the United States. But it is still a much better book than nearly anything else available from American university researchers on the subject.

Park Statue Politics, it is hoped, will be the beginning of a long-overdue reassessment of the history that underlies the historiography and the politics that distort our understanding of the past.

Title of Book: Park Statue Politics: World War II Comfort Women Memorials in the United States

Publisher: E-International Relations Publishing, 2019

Authors: Thomas J. Ward and William D. Lay

To learn more: Follow this link to learn more about the book at the publisher’s website or to learn how to purchase a copy.

Author: Jason Morgan

No comments:

Post a Comment