Books

›

Politics, Philosophy & Social Sciences

›

Politics & Government

Hardcover

$60.33

Paperback

$37.87

Other Used and New from $37.33

Delivery

Collection

Buy new:

$37.87

FREE delivery Saturday. Order within 22 hrs 47 mins

Deliver to Sejin - Campbelltown 5074

Only 1 left in stock.

Add to Cart

Buy Now

Ships from

Amazon AU

Sold by

Amazon AU

Returns

Eligible for change of mind returns within 30 days of receipt

Payment

Secure transaction

Add a gift receipt for easy returns

Add to Wish List

Add to Baby Wishlist

New (15) from

$37.33$37.33

Roll over image to zoom in

Follow the author

Pankaj MishraPankaj Mishra

Follow

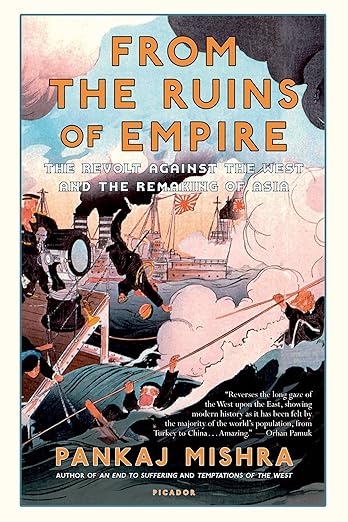

From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt Against the West and the Remaking of Asia Paperback – 27 August 2013

by Pankaj Mishra (Author)

4.4 out of 5 stars 171

See all formats and editions

A Financial Times and The Economist Best Book of the Year and a New York Times Book Review Editors' Choice

A SURPRISING, GRIPPING NARRATIVE DEPICTING THE THINKERS WHOSE IDEAS SHAPED CONTEMPORARY CHINA, INDIA, AND THE MUSLIM WORLD

A little more than a century ago, independent thinkers across Asia sought to frame a distinct intellectual tradition that would inspire the continent's rise to dominance. Yet this did not come to pass, and today those thinkers--Tagore, Gandhi, and later Nehru in India; Liang Qichao and Sun Yat-sen in China; Jamal al-Din al-Afghani and Abdurreshi al Ibrahim of the Ottoman Empire--are seen as outsiders within the main anticolonial tradition. But as Pankaj Mishra demonstrates in this enthralling portrait of like minds, Asia's revolt against the West is not the one led by faith-fired terrorists and thwarted peasants; rather, it is rooted in the ideas of these once renowned intellectuals. Now, when the ascendency of Asia seems possible as never before, From the Ruins of Empire is as necessary as it is timely--a book indispensable to our understanding of the world and our place in it.

===

Product description

Review

"Reverses the long gaze of the West upon the East, showing modern history as it has been felt by the majority of the world's population, from Turkey to China...Amazing." --Orhan Pamuk

"Essential reading for everyone who is interested in the processes of change that have led to the emergence of today's Asia." --Amitav Ghosh, The Wall Street Journal

"Timely and important...An astute and entertaining synthesis of these neglected histories." --Hari Kunzru, The New York Times Book Review

"From the Ruins of Empire retains the power to instruct and even to shock. It provides us with an exciting glimpse of the vast and still largely unexplored terrain of anticolonial thought that shaped so much of the post-Western world in which we now live." --Financial Times (London)

"Subtle, erudite, and entertaining." --The Economist

"History is sometimes a contest of narratives. Here Pankaj Mishra looks back on the 19th and 20th centuries through the work of three Asian thinkers: Jamal al-Din Afghani, Liang Qichao and Rabindranath Tagore. The story that emerges is quite different from that which most Western readers have come to accept. Enormously ambitious but thoroughly readable, this book is essential reading for everyone who is interested in the processes of change that have led to the emergence of today's Asia." --Amitav Ghosh, author of Sea of Poppies and River of Smoke

"With uncommon empathy, Mishra has excavated a range of ideas, existential debates, and spiritual struggles set in motion by Asia's rude collision with the West, leading to outcomes no one could have predicted but which, after his account, seem more comprehensible--and that is no mean achievement. Above all, Mishra sheds new light on an important part of our collective journey, the inner and outer turmoil we inhabited, the price we paid, and what we did to each other along the way. We might yet learn from it and redeem ourselves in some measure." --Namit Arora, 3 Quarks Daily

"After Edward Said's masterpiece Orientalism, From the Ruins of Empire offers another bracing view of the history of the modern world. Pankaj Mishra, a brilliant author of wide learning, takes us through, with his skillful and captivating narration, interlinked historical events across Japan, China, Turkey, Iran, India, Egypt, and Vietnam, opening up a fresh dialogue with and between such major Asian reformers, intellectuals, and revolutionaries as Liang Qichao, Tagore, Jamal al-din al-Afghani, and Sun Yatsen." --Wang Hui, author of China's New Order and The Rise of Modern Chinese Thought and Professor of Chinese Intellectual History at Tsinghua University, Beijing

"Pankaj Mishra has produced a riveting account that makes new and illuminating connections. He follows the intellectual trail of this contested history with both intelligence and moral clarity. In the end we realise that what we are holding in our hands is not only a deeply entertaining and deeply humane book, but a balance sheet of the nature and mentality of colonisation." --Hisham Matar

"Mishra's survey knowledgeably presents an intellectual history of anti-imperialism." --Booklist

"Meticulous scholarship.....History, as Mishra insists, has been glossed and distorted by the conqueror....[This] passionate account of the relentless subjugation of Asian empires by European, especially British, imperialism, is provocative, shaming and convincing." --Michael Binyon, Times (London)

"Superb and groundbreaking. Not just a brilliant history of Asia, but a vital history for Asians." --Mohsin Hamid, author of How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia

"Fascinating...a rich and genuinely thought-provoking book." --Noel Malcolm, Telegraph

"One can only be thankful for writers like Mishra. From The Ruins Of Empire is erudite, provocative, inspiring and unremittingly complex; a model kind of non-fiction for our disordered days....May well be seen in years to come as a defining volume of its kind." --Stuart Kelly, Scotsman

"Deeply researched and arrestingly original...this penetrating and disquieting book should be on the reading list of anybody who wants to understand where we are today." --John Gray, Independent

"Mishra has no time at all for big, broad-brush accounts of western success contrasted with eastern hopelessness. Instead, he is preoccupied by the tragic moral ambivalence of his tale. . . From the Ruins of Empire gives eloquent voice to their curious, complex intellectual odysseys as they struggled to respond to the western challenge . . . Luminous details glimmer through these swaths of political and military history." --Julia Lovell, The Guardian

"[An] ambitious survey of the decline and fall of Western colonial empires and the rise of their successors. . . A highly readable and illuminating exploration of the way in which Asian, and Muslim countries in particular, have resented Western dominance and reacted against it with varying degrees of success." --The Tablet (UK)

"From the Ruins of Empire jolts our historical imagination and suddenly places it on the right, though deeply repressed, axis. It is a book of vast and wondrous learning and delightful and surprising associations that will give a new meaning to a liberation geography. From close and careful readings of some mighty Asian intellectuals of the last two centuries who have rarely been placed in this creative and daring conversation with each other, Pankaj Mishra has discovered and revealed, against the grain of conventional and cliched bifurcations of 'The West and the Rest, ' a continental shift in our historical consciousness that will define a whole new spectrum of critical thinking." --Hamid Dabashi, Columbia University

About the Author

Pankaj Mishra is the author of From the Ruins of Empire, Age of Anger, and several other books. He is a columnist at Bloomberg View and writes regularly for The Guardian, the London Review of Books, and The New Yorker. A fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, he lives in London.

Product details

ASIN : 1250037719

Publisher : Picador USA; Reprint edition (27 August 2013)

Language : English

Paperback : 368 pages

ISBN-10 : 9781250037718

ISBN-13 : 978-1250037718

Dimensions : 13.97 x 3.43 x 20.96 cm

Best Sellers Rank: 415,182 in Books (See Top 100 in Books)

304 in History of Afghanistan

431 in History of Turkey

728 in Globalization (Books)

Customer Reviews: 4.4 out of 5 stars 171

About the author

Follow authors to get new release updates, plus improved recommendations.

Pankaj Mishra

Follow

Pankaj Mishra

===

From other countries

Normand Bianchi

5.0 out of 5 stars Comment les nations colonisées de l'Asie ont vécu l'impérialisme occidental

Reviewed in Canada on 16 October 2020

Verified Purchase

Une lecture qui nous fait comprendre les mouvements de libération à travers le monde face aux exactions du Royaume uni et des autres puissances occidnetales

Report

Translate review to English

Claire MacGregor

5.0 out of 5 stars Critique of From the Ruins of Empire by Pankaj Mishra

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 4 January 2014

Verified Purchase

This has been a mind-altering read. Far from being an anti-imperial rant, it is a careful compilation of the writings of three observers of European expansion into the east, chiefly British, French, Dutch and US. The annihilation of the Russian fleet by Japan in 1905 showed that Europeans were not invincible, and led to serious questioning of the West's colonising ways. Jamal al-Din al Afghani was born in Persia, Liang Qichao was Chinese and Rabindranath Tagore was Bengali, and all became well-known writers and critics of the "white man's" imperial pretensions. While the West spoke darkly of the "Yellow Peril", the East referred to the "White Disaster". Anyone interested in our troublous times could find this book enlightening.

Report

Harry L. Stille

5.0 out of 5 stars A New Look at the Ruins of Empire

Reviewed in the United States on 20 January 2013

Verified Purchase

From the Ruins of Empire: The Intellectual of Who Made Asia, by Pankaj Mishra presents an important world history as seen through the eyes of a number of internationally acclaimed Asian writers as well as the thoughts of some lesser known figures and events. This book is timely, thought provoking and a must read for anyone desiring a better understanding of events in today's Middle and Far East . The author is well informed and balanced, abstaining from any attempt to replace a Euro-centric view, with an Asia-centric one.

Opening with the story of the first non-European country to vanquish a European power since the Middle Ages (the 1905 Japanese victory over the Russian navy) the awakening and reverberations of which provided the theme of this book.

An introductory quote of a world famous philosopher serves as a front piece warning of a dated but arrogant grand Western historical speculation: wherein Hegel declared China and India of no concern to world history.

Reflecting changes in world perspective, this books focus is on this very area -- Asia. Since that part of the globe was once the object of Western Imperial adventures, the author, through the thoughts and comments of various Asian intellectuals, expands his interest as he probes the political, economic, thoughts and ideologies, underlying Western colonial attitudes.

It is here, that one witnesses the working out through adaptation and copying of the Western concept of "modernity:" the arrogant and racist bias of the occupiers and the concomitant resentment, envy and quiescent arrogance of the colonized The result is the social, political conflict and confusion emerging from decolonization and the rise of independent nation states.

The main protagonists in this book are two itinerant thinkers and activists: Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1873-97) a Muslim whose writings prepared the way for Ataturk, Nasser, Ayatollah Khomeini, and still animates the politics of Islamic societies. The other is Liang Qichao (1873-1929) perhaps China's foremost modern intellectual who bequeathed his obsessions with building state power to Mao Zedong Both of these men became major forces for change. Of particular note is the observation that the prevailing concern with Islam as a religion is not perhaps as significant as an apparent societal propensity for "fanaticism and despotism." By opening up new perspective Mishra hopes that we may be convinced that the "assumptions of Western power -- increasingly untenable-- are no longer a reliable vantage point and may even be dangerously misleading."

The book is full of astounding quotes from various Asian writers, some of which demonstrate a high degree of discernment and prescience, as well as an accurate and succinct summary of the historical situation.

The author closes with a very important assessment and warning, namely that in the future we may experience even bloodier conflicts generated by the need for precious resources as we strive towards world wide modernization. He categorically states that for China and India to enjoy the lifestyles of Europeans and Americans - "is as absurd and dangerous a fantasy as anything dreamt of by Al-Qaeda." Most sobering is the thought provoking conclusion: "the universal triumph of Western modernity which turns the revenge of the East into something darkly ambiguous, and all its victories truly Pyrrhic."

Harry L. Stille

8 people found this helpful

Report

Amazon Customer

4.0 out of 5 stars Four Stars

Reviewed in Canada on 4 February 2016

Verified Purchase

Good explanation of what is happening in the Middle East. Its getting even for colonialism and imperialism

Report

dmiguer

4.0 out of 5 stars Empire From Within

Reviewed in the United States on 18 November 2021

Verified Purchase

"There is no day in which foreigners do not grab a part of Islamic lands. England has occupied Egypt, the Sudan and India; the French have taken posession of Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria; the Dutch have become rulers of Java; Russia has captured West Turkistan. Few Islamic countries have remained independent." - Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, 1896

"If there is no moral culture in the schools, no teaching of patriotism, students will no longer know they have their own country. The virtuous man will be an employee of foreigners, the degenerate man a traitor to Chinese. In the state of our armaments we see one road to weakness; in the stagnation of culture a hundred more." - Liang Qichao, 1896

"Europe has lost her moral prestige in Asia. She is no longer regarded as the champion of fair dealing and high principles but as an upholder of Western race supremacy and exploiter outside of her own borders." - Rabindranath Tagore, 1921

Pankaj Mishra opens this 2012 book in the Tsushima Straight where a small Japanese fleet sunk much of the Russian Navy in 1905, winning Korea and Manchuria for Emperor Meiji. The colonies around Asia took notice, their politicians and intellectuals astonished and joyful that a great empire had surrendered to an eastern nation, one to become imperialist itself. The West took notice too; soon they would taste the bitterness as colonies fell. Mishra focuses on three thinkers of the period, Iranian, Chinese and Indian activists. Other familiar faces are in the mix: Gandhi, Ho Chi Minh, Sun Yat-sen, Mao Zedong, Sayyid Qutb and Kemal Ataturk, each who had responded to western encroachment in different ways.

In Egypt Napoleon spearheaded a 1798 campaign to replace colonies lost in America and compete with Britain in Asia. With a group of scientists and artists in tow, he intended to record the dawn of Enlightenment in the East. The intrusion upset an Islamic order in Africa, as the British had in Asia. Initially dismissive of infidel institutions and technology, observers noted changes were needed to meet a challenge by the West. While France lost in Egypt, Britain made strides subjugating India. Napoleon finished in 1815, great European powers turned east towards Asia. Within decades Burma, Singapore, Malay, Java and Vietnam were divided between them. Egypt soon fell to Britain and North Africa to France.

In Iran Ali Shariati was a major guide of the 1979 Islamic Revolution after the western overthrow of democracy in 1953. He had studied Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, a late 19th century activist who traveled in Asia and Europe. Al-Afghani was a father of Pan-Islamist and Pan-Arabist thought. While others urged assimilation he sought resistance to racial and religious takeover. He witnessed the Indian Rebellion of 1857, agitating for Afghan revolt in the 1878 Anglo-Afghan war. In Istanbul he fought for reform of education and law, in Cairo he criticized reliance on foreign finance. He went to Russia to enlist support against the British, inspiring 1891 riots in Iran against the Shah's leasing of national resources.

In China Japan's modernization and victory in the 1895 war over Korea loomed above writer and activist Liang Qichao, who would later influence Mao Zedong. China was mired in debt due to war indemnities and western loans. Sun Yat-sen, fomenting uprise against the Qing, was exiled to Japan. Liang and others pressed to reform the Confucian system and renew its ancient values. In the 100 Day Reforms the young Emperor was imprisoned by the Empress Dowager. Liang fled to Japan, witnessing the birth of Pan-Asianism as the US seized the Philippines in 1898. The Boxer Rebellion of 1900 attacked foreigners, the Qing chastised. Liang mulled over revolution as social darwinism threatened extinction.

In America Liang traveled coast to coast, meeting JP Morgan and Theodore Roosevelt. Woodrow Wilson demanded closed doors of trade to be battered down. The US took the Panama Canal as British had in Suez. Blacks and Asians denied rights, Japanese autocracy was tempting to the east. With the Qing deposed, western ally Japan annexed German colonies after WWI. China expected their return in the 1919 Peace Talks but requests were denied. Liang's protests to end extraterritorial law, unequal treaties and war indemnities went unrealized. Ho Chi Minh petitioned in vain for Vietnamese self rule as did Gandhi for India. The Ottoman carcass was picked clean in Palestine, Mesopotamia, Maghreb, Caucasus and Balkans.

In the Mideast riots obtained a degree of self-rule. From the Russian Soviet, Lenin revealed secret deals the Big Four had made. Disillusioned Vietnamese and Indonesians defected to socialism. Ataturk expelled Allied forces in Istanbul. Protests pushed Japan from Shandong and the Chinese Communist Party was formed in 1921. Broken promises to India launched Gandhi as leader. Rabindranath Tagore, a Indian Nobel Prize poet, renounced his knighthood. Born to a family of Bengali businessmen who worked with the British, he was exposed to western ideas. He argued for a spiritual return to Indian ideals, but opposed Gandhi's xenophobia and westernizers who emulated Japan and Turkey in sweeping away the past.

The syncretic appoaches of al-Afghani, Liang and Tagore were undermined by younger leaders' urgent need to fight militarists within and imperialists without. Disenchanted reformers were pushed aside by hardline nationalists and communists. The League of Nations was portrayed as a plot against Japan's liberation of Asia and defeat of communism in China. Oil embargoes could only be met by seizing the mainland and islands. Such was the justification as the Philippines, Singapore, Malaya, Hong Kong, Dutch East Indies, French Indochina and Burma colonies fell in 1941. Japan's 'Greater East Asian Prosperity Plan' mocked 'Asia for Asians' and gave way to murder and plunder in the region.

The thinkers in this study fell into three main groups: those who advocated for a return to traditional values, some who sought a synthesis with modern progress and others who called for wholesale westernization. The three examples Mishra chooses to highlight were synthesizers who wished to retain aspects of their culture and strengthen them with industrialization. It was a valid goal but the distinctions that made the world diverse disappeared into indistinguishable modernity. As a history it raises interesting questions. Can countries retain cultural characteristics as they connect in a globalized world? At some point we may be left only with politics and religion to keep us apart, for better or worse.

3 people found this helpful

Report

sarah hargreaves

4.0 out of 5 stars Very interesting. I don't think loosing some of the ...

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 3 March 2016

Verified Purchase

Very interesting. I don't think loosing some of the detail would detract from the points made though.

Report

cynthia.campbell@oslo.online.no

5.0 out of 5 stars A view from the otherside.

Reviewed in the United Kingdom on 7 November 2012

Verified Purchase

We are so used to learning our history from a from a British, or at least European side that it is fascinating to learn something of how great minds from other cultures saw the same events and ideas. This book is clearly and well-written, and I find that I have learnt a great deal from it.

2 people found this helpful

Report

Not Moses

5.0 out of 5 stars A =Vital= Primer for Anyone who deals with Former Colonials

Reviewed in the United States on 4 February 2022

Verified Purchase

On the strength of having read two earlier books by Mishra, and in the midst of exploring the upshots of the European colonialization of much of the rest of the planet, I bagged a copy of this one. And I'm glad I did.

Mishra =knows= his subject and has produced an epic thesis covering the globe from the shores south of Gibraltar to the Yellow Sea. More than that, he names the names of those whose writing and lectures enflamed one independence movement after another... most of which very few Westerners know much about.

From the Ruins... should at the very least be required reading for anyone already in or wanting to be in professional diplomacy and statecraft, as well as those whose in private industry tasked with the challenges of dealing with the lingering upshots of Western colonial abuse of peoples who are now way past mere "emergence" and more than merely empowered to make sure it doesn't happen again.

One person found this helpful

Report

Shamim Sheikh

5.0 out of 5 stars A must read for those who want to understand the current state of the world

Reviewed in Canada on 13 March 2014

Verified Purchase

This book presents the 18th, 19th and 20th century Europe, Middle East and India in a unique manner. It is a more honest analysis of the affairs than most other books. It also helps explain the situation in the world today. Great work by Pankaj Mishra.

Report

LostInSpace

5.0 out of 5 stars Read me, this will make you rethink your assessment of where the world is today

Reviewed in the United States on 11 August 2023

Verified Purchase

And extraordinarily important book. It helps me look at current world events with a longer view, and explains the missteps along the way, and how we ended up a society across the world that values consumption in the name of progress.

Report

===

This article is more than 11 years old

Review

From the Ruins of Empire by Pankaj Mishra – review

This article is more than 11 years old

An engaging study explores Asia's intellectual response to western imperialism

Ben Shephard

Sun 5 Aug 2012 09.05 AEST

Share

6

The Asian world was in crisis in the late 19th century. From China to India to Turkey, societies that had stood largely unchanged for centuries were powerless to resist western armies and commerce. Appalled by the vulgarity and materialism of the white barbarians, eastern elites nonetheless recognised that something would have to be done. But what? In this erudite and engaging book, Pankaj Mishra identifies three main strands in the Asian response to the threat of western modernism: reactionaries who believed that the continent's long-standing religious traditions would ultimately prevail; moderates who wanted to cherry-pick from the western toolkit while leaving their own societies largely unchanged; and revolutionaries such as Atatürk and Mao Zedong who thought that nothing less than radical secularisation and a new ideology would galvanise their societies to compete in the modern world.

What gives From the Ruins of Empire its charm and richness of texture, however, is that its main focus is not on major players such as Gandhi and Mao, but on two little-known and seemingly ineffectual intellectuals whose writings would inspire later generations. Jamal al-Din al-Afghani was a comparable figure to Alexander Herzen or Karl Marx: a peripatetic journalist, teacher and agitator, working in cafes, mosques and homes, expelled in turn from Afghanistan, India, Turkey and Egypt between 1860 and 1900. A contradictory and inconsistent thinker who tailored his ideas and his wardrobe to local circumstances, al-Afghani was a Persian-born Shia Muslim who pretended to be a Sunni from Afghanistan, and in his early days a liberal – critical of the fanaticism and political tyranny that held back many Islamic societies and an advocate of education for women. He "preached the necessity of reconsidering the whole Islamic position and, instead of clinging to the past, of making an onward intellectual movement in harmony with modern knowledge". But he never wavered in his hatred of the British and in his later years became an Islamic ideologue, advocating armed struggle and violent resistance – though not, as with Osama bin Laden, terror. Al-Afghani's only political achievement was to organise a smoking boycott which forced the Shah of Persia to cancel a tobacco monopoly granted to a foreign company. He died prematurely in 1897, a bitter and disappointed man. Yet his legacy was enormous: he coined the vocabulary of 20th-century anti-western Islamic rhetoric.

Six years after al-Afghani's death, the Chinese intellectual Liang Qichao visited the United States for the first time. As someone who believed that China must make a radical break with Confucianism, he was hoping to find inspiration. Instead he was appalled by the inequalities in wealth and the political corruption he witnessed; the squalid tenements of New York and the way that white Americans treated their black and Chinese fellow citizens. American democracy, he decided, did not provide the model for China. "No more am I dizzy with vain imaginings," he wrote. "No longer will I tell a tale of pretty dreams. In a word, the Chinese people must for now accept authoritarian rule; they cannot enjoy freedom." But perhaps, in 20, 30 or 50 years' time, he added, it might be possible to "give them Rousseau to read, and speak to them of Washington".

Prophetic words – no wonder Liang would influence Mao Zedong. Yet Liang's involvement in practical politics proved as disastrous as al-Afghani's. He was eclipsed by Sun Yatsen during the Chinese revolution of 1911 and, in the chaos that followed, threw in his lot with a corrupt warlord. His last significant act was to form part of the Chinese delegation to the Versailles peace conference, which vainly urged President Wilson to dismantle the western empire in the east, a rebuff that led many Asian intellectuals to turn to Moscow and communism – most famously, Ho Chi Minh, who had hired a morning suit in the hopes of seeing the American president. By then, however, the carnage and savagery of the first world war had taken much of the lustre off western materialism and worship of science: in hindsight, western hegemony in the far east was doomed. Japan's attempt to become an imperial power herself, having once been the patron of Asian nationalism, only accelerated that process.

When he reaches the interwar period, Mishra shifts gear, away from intellectual biography towards historical essay. He gives an excellent outline of the different paths to modernity taken by the main Asian countries, managing to keep thematic control of increasingly divergent narratives, though he does stud the text with too many names that are unfamiliar to the western reader. Just when it seems that Mishra will end in full triumphalist mode, he concludes in a final twist that, while Asian societies have by and large got their revenge for their past humiliations, they have in the process lost many of the values which once distinguished them. Both India and China now have the inequalities of wealth that so disturbed visitors to the west a hundred years ago.

As his hatchet job on Niall Ferguson in the London Review of Books last year showed, Mishra is no mean polemicist, but he is also an intellectual historian who can skilfully paint in background, simplify boldly to open up broad perspectives on the past, and popularise without condescension. Of course, a book of this scope has to be selective – one major omission is the impact of oil on modern Islamic society – but overall it gives a voice to characters often ignored by western historians and makes an eloquent contribution to the "west versus the rest" debate.

You've read 12 articles in the last year

===

A Greater Asia

Share full article

By Hari Kunzru

Sept. 21, 2012

In 2011, the Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei exhibited 12 bronze animal heads representing the signs of the Chinese zodiac outside the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan. The heads were enlarged replicas of a set designed in the 18th century by two European Jesuits for the emperor Qianlong and displayed in the gardens of the Yuanmingyuan, the emperor’s Old Summer Palace. At the time of the exhibition, Ai had disappeared into detention in China. The political controversy overshadowed the work itself, which posed its most searching questions not to the Chinese government, but to the West.

In 1860, during the Second Opium War, the Old Summer Palace was ransacked and torched by French and British soldiers. In “From the Ruins of Empire,” his timely and important history of Asian intellectual responses to Western colonialism, Pankaj Mishra quotes one looter who said that to describe “the splendors before our astonished eyes, I should need to dissolve specimens of all known precious stones in liquid gold for ink, and to dip it into a diamond pen tipped with the fantasies of an oriental poet.” The zodiac heads were among the spoils, which disappeared for generations into European art collections. The destruction of the Old Summer Palace, all but forgotten by its perpetrators, still excites shame and anger in China, where it is seen as a symbol of Western imperial brutality and a reminder of the consequences of national military weakness.

Mishra, the Indian essayist and novelist, shows how, like their European and American counterparts, Asian intellectuals of the 19th and 20th centuries responded to the colonial encounter by constructing a binary opposition between East and West. From Ottoman Turkey to Meiji Japan, writers struggled in the face of the humiliating experience of subjugation. The superior technology and organization of the imperial powers were self-evident. What was the correct response? Could new innovations and modes of production be grafted onto existing social structures, or did cherished ways of life and thought have to be abandoned? The question of what to accept, what to adapt and what to reject from “the West” remains central in contemporary Asian politics; “From the Ruins of Empire” reveals much — not just about why a Chinese artist would erect replicas of stolen national treasures in a Western city, but about the ideological underpinnings of the Iranian revolution and India’s dogged pursuit of scientific and technical excellence.

ADVERTISEMENT

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Mishra tells this story through the biographies of three public intellectuals: the itinerant Persian-born agitator Jamal al-Din al-Afghani; the Chinese reformer Liang Qichao; and Rabindranath Tagore, poet and Nobel laureate, vaunted as the embodiment of traditional Eastern wisdom. Al-Afghani (1838-97) claimed to be a Sunni Muslim from Afghanistan but was actually a Persian Shiite. He traveled to India and by the age of 28 was in Kabul, trying to play off the British against the Russians in the “Great Game.” A man of flexible political allegiances and fond of the Koranic maxim “God does not change the condition of a people until they change their own condition,” he became an early apostle of pan-Islamism. He hoped to restore authenticity to a religion he saw as fundamentally rational, open to change and innovation, but which had become corrupt. After his expulsion from Kabul he traversed the Muslim world, from the mosques of Cairo to the drawing rooms of Istanbul, where he importuned the sultan to launch Muslim resistance to the West.

Editors’ Picks

Making a Meal for a Date: When Is the Right Time?

They Built Three Homes Together. Now She Must Do It Alone.

Do You Need a Home Watcher? Here’s What One Could Do for You.

Image

Credit...Illustration by Joanna Neborsky

Liang Qichao (1873-1929) sought a middle way for China between the intellectual sclerosis of the Qing imperial court and the destructive transformation sought by the Communists. In 1898, having caught the ear of the 26-year-old emperor Guangxu, he and his friend and mentor Kang Youwei tried to initiate a rapid process of reform. It lasted only about 100 days before the dowager empress, in retirement at the Old Summer Palace, “took it upon herself to squash her little nephew.” Liang barely escaped with his life, and revolution, Mishra writes, became “inevitable.”

Kang and Liang were instrumental in the formulation of a decisive new category in Chinese political discourse: “the people.” Traditionally, popular opinion was considered irrelevant. Now they proposed that the state needed the consent of an educated citizenry to govern. Kang even believed that such reforms as mass education and free elections could realize the Confucian notion of ren (benevolence), a “utopian vision of an inevitable universal moral community, where egoism and the habit of making hierarchies would vanish.”

After the failed 1898 reforms, Liang went into exile in Japan, which in the Meiji period was as much a hotbed of international revolutionary plotting as London or Paris. It was a cosmopolitan milieu in which radicals from across Asia met, studied and argued in an atmosphere whose prevailing sentiments were “cultural pride, political resentment and self-pity.” Herbert Spencer, John Stuart Mill, Adam Smith and T. H. Huxley had been newly translated into Chinese, and social Darwinism became especially influential.

Under this influence, Liang moved away from a cosmological Confucianism, in which order was static and the emperor the “polestar,” toward a revolutionary notion of total social mobilization. The motivating force of modern international competition stems, he wrote, “from the citizenry’s struggle for survival which is irrepressible according to the laws of natural selection and survival of the fittest. Therefore the current international competitions are not something which only concerns the state, they concern the entire population.” The influence of Liang’s realist theory of power is abundantly evident in contemporary Chinese politics. Mishra notes dryly that liberal democracy “did not seem necessary to national self-strengthening.”

ADVERTISEMENT

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

It was Liang who invited the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) to Shanghai to lecture in 1924. By the end of the 19th century, Hindu intellectuals had adopted a posture of spiritual superiority, disparaging modern civilization as a “machine” and Europeans (in the unforgettable words of Swami Vivekananda) as “wild animals . . . insane in their lust, drenched in alcohol from head to foot.” Tagore hoped that the East might temper the machinelike nature of modern civilization, “substituting the human heart for cold expediency,” but despite such lofty posturing, India had become a sort of cautionary tale for China, a country of humiliated British slaves. When Tagore spoke at a meeting in Hankou, he met with heckles and slogans saying: “Go back, slave from a lost country! We don’t want philosophy, we want materialism!”

Tagore, the apparently unworldly romantic, transformed the consciousness of his region through essays, poems and songs, two of which are now the national anthems of India and Bangladesh. Likewise, al-Afghani’s mission to redeem the fallen Muslim world and Liang’s desire to mobilize the popular will for national transformation have both shaped a century of Asian political aspirations. Mishra’s astute and entertaining synthesis of these neglected histories goes a long way to substantiating his claim that “the central event of the last century for the majority of the world’s population was the intellectual and political awakening of Asia.”

FROM THE RUINS OF EMPIRE

The Intellectuals Who Remade Asia

By Pankaj Mishra

Illustrated. 356 pp. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. $27.

==

Profile Image for Zanna.

Zanna

676 reviews

1,010 followers

Follow

December 28, 2017

Mishra's approach here can't be faulted; it would be preposterous to offer the sweeping statements and crisp conclusions of the sixth chaper 'Asia Remade' without carefully laying the foundations in the previous five, painstakingly excavating the neglected work and histories of thinkers like Jamal al-din al-Afghani and Liang Qichao, whose shadows lie tall across the decades in myriad shapes: from Mao Tse-Dong to the Confucian resurgence, from Ayatollah Khomeini to Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. For me it was a bit of an uphill slog, but all worth it for the exhilarating freewheeling down from the top

Commonplace critique of colonisation tends to assume a passive Asia in subdued thrall, an orientalist picture in itself. Mishra energetically corrects that misconception here, showing how colonial powers were seen by Asian intellectuals and how various strands and flavours of resistence were built up. For most of the book I felt that everyone, Mishra included, was giving too much quarter to coloniser epistemology, which only begin to partially unravel at the hands of Gandhi and Tagore and in the later chapters. It is interesting in itself though that ideas like social Darwinism and scientific materialism caught on and wrought significant changes to Asian state structures and societies. 'Western' ideas were not merely assimilated but furiously and critically debated, adapted, edited, and in the case of the nation state concept, eventually used to overthrow the imperial powers and to remake Asia. The thinkers Mishra follows change their minds in the course of their intellectual careers; first imagining how the key tenets of Western success might work for Islam or the Chinese, and later, on some level recognising the West as a disaster to its own populations as well as others.

Mishra has been astonishingly effective at synthesising and condensing whole libraries of background reading into this focussed, highly structured work. Of thousands of possible strands, he has selected a handful, and woven them into coherence, into something that can be digested and absorbed usefully for reflection and discussion. I was struck by what I felt to be its dispassionate tone; until the concluding chapters, the atrocities of empire were treated almost casually, and strands of opposition are discussed quite matter-of-factly, creating an impression of even-handedness and objectivity. But of course, I have been sheltered from these shameful histories.

What is outside the scope of this history is the ground-level perspective. I suppose many readers will be much more familiar with this view, which is the domain of literature, but the thinkers Mishra follows addressed themselves mainly to elites, at times academic, but mainly political, and only late in their careers realised that cultural change comes from the roots of the grass. Thus, the hinges of Mishra's story are unoiled by vernacular voices, and women make almost no appearance at all. While I found it an edifying read, there was more duty than pleasure in the text for me!

69 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Dmitri.

Dmitri

216 reviews

190 followers

Follow

October 11, 2023

"There is no day in which foreigners do not grab a part of Islamic lands. England has occupied Egypt, the Sudan and India; the French have taken posession of Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria; the Dutch have become rulers of Java; Russia has captured West Turkistan. Few Islamic countries have remained independent." - Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, 1896

"If there is no moral culture in the schools, no teaching of patriotism, students will no longer know they have their own country. The virtuous man will be an employee of foreigners, the degenerate man a traitor to Chinese. In the state of our armaments we see one road to weakness; in the stagnation of culture a hundred more." - Liang Qichao, 1896

"Europe has lost her moral prestige in Asia. She is no longer regarded as the champion of fair dealing and high principles but as an upholder of Western race supremacy and exploiter outside of her own borders." - Rabindranath Tagore, 1921

************

Pankaj Mishra opens this 2012 book in the Tsushima Straight where a small Japanese fleet sunk much of the Russian Navy in 1905, winning Korea and Manchuria for Emperor Meiji. The colonies around Asia took notice, their politicians and intellectuals astonished and joyful that a great empire was defeated by an eastern nation, one to become imperialist itself. The West took notice too; soon they would taste the bitterness as colonies fell. Mishra focuses on three thinkers of the period, Iranian, Chinese and Indian activists. Other familiar faces are in the mix: Gandhi, Ho Chi Minh, Sun Yat-sen, Mao Zedong, Sayyid Qutb and Kemal Ataturk, each who had responded to western encroachment in different ways.

In Egypt Napoleon spearheaded a 1798 campaign to replace colonies lost in America and compete with Britain in Asia. With a group of scientists and artists in tow he intended to record the dawn of Enlightenment in the East. The intrusion upset an Islamic order in Africa as the British had in Asia. Initially dismissive of infidel institutions and technology, observers noted changes were needed to meet a challenge by the West. While France lost in Egypt, Britain made strides subjugating India. Napoleon finished in 1815, the European powers turned east towards Asia. Within decades Burma, Singapore, Malay, Java and Vietnam were divided between them. Egypt soon fell to Britain and North Africa to France.

In Iran Ali Shariati was a major guide of the 1979 Islamic Revolution after the western overthrow of democracy in 1953. He had studied Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, a late 19th century activist who traveled in Asia and Europe. Al-Afghani was a father of Pan-Islamist and Pan-Arabist thought. While others urged assimilation he sought resistance to racial and religious takeover. He witnessed the Indian Rebellion of 1857, agitating for Afghan revolt in the 1878 Anglo-Afghan war. In Istanbul he fought for reform of education and law, in Cairo he criticized reliance on foreign finance. He went to Russia to enlist support against the British, inspiring 1891 riots in Iran against the Shah's leasing of national resources.

In China Japan's modernization and victory in the 1895 war for Korea loomed over writer and activist Liang Qichao who would later influence Mao Zedong. China was mired in debt due to war indemnities and western ‘loans’. Sun Yat-sen, fomenting uprise against the Qing, was exiled to Japan. Liang and others pressed to reform the Confucian system and renew its ancient values. In the 100 Day Reforms the young Emperor was imprisoned by the Empress Dowager. Liang fled to Japan, assisting the birth of Pan-Asianism as the US seized the Philippines in 1898. The Boxer Rebellion in 1900 attacked foreigners, the Qing chastised. Liang mulled over revolution as social darwinism threatened extinction.

In America Liang traveled coast to coast, meeting JP Morgan and Theodore Roosevelt. Woodrow Wilson demanded closed doors of trade to be battered down. The US took the Panama Canal as British had in Suez. Blacks and Asians denied rights Japanese autocracy was tempting to the east. With the Qing deposed, western ally Japan annexed German colonies after WWI. China expected their return in the 1919 Peace Talks but requests were denied. Liang's protests to end extraterritorial law, unequal treaties and war indemnities went unrealized. Ho Chi Minh petitioned in vain for Vietnamese self rule as did Gandhi for India. The Ottoman carcass was picked clean in Palestine, Mesopotamia, Maghreb, Caucasus and Balkans.

In the Mideast riots obtained a degree of self-rule. From the Russian Soviet Lenin revealed secret deals the Big Four had made. Disillusioned Vietnamese and Indonesians defected to socialism, Ataturk expelled Allied forces in Istanbul. Protests pushed Japan from Shandong and the Chinese Communist Party was formed in 1921. Broken promises to India launched Gandhi as leader. Rabindranath Tagore, Indian Nobel Prize poet, renounced his knighthood. Born to a family of Bengali businessmen who worked with the British he was exposed to western ideas. He argued for a spiritual return to Indian ideals, but opposed Gandhi's xenophobia and westernizers who emulated Japan and Turkey in sweeping away the past.

The syncretic approaches of al-Afghani, Liang and Tagore were superseded by younger leaders urgent need to fight militarists within and imperialists without. Disenchanted reformers were pushed aside by hardline nationalists and communists. The League of Nations was portrayed as a plot against Japan's liberation of Asia and defeat of communism in China. Oil embargoes could only be met by seizing the mainland and islands. Such was the justification as the Philippines, Singapore, Malaya, Hong Kong, Dutch East Indies, French Indochina and Burma colonies fell in 1941. Japan's 'Greater East Asian Prosperity Plan' mocked 'Asia for Asians' and gave way to murder and plunder in the region.

The thinkers in this study fell into three main groups: those who advocated for a return to traditional values, some who sought a synthesis with modern progress and others who called for wholesale westernization. The three examples Mishra chooses to highlight were synthesizers who wished to retain aspects of their culture and strengthen them with industrialization. It was a valid goal but the distinctions that made the world diverse disappeared into undifferentiated modernity. As a history it raises interesting questions. Can countries retain cultural characteristics as they connect in a globalized world? At some point we may be left only with politics and religion to keep us apart, for better or worse.

china

colonialism

india

...more

50 likes

2 comments

Like

Comment

Profile Image for William2.

William2

783 reviews

3,329 followers

Follow

January 5, 2013

An interesting history of anti-colonial intellectual life in the East during the greatest days of Imperialism. Mishra's new book is one much needed by Western readers. It's a necessary corrective. It's loaded with information about intellectuals in the Muslim world, China and India most of whom I have never heard of before. Each of these men--Jamal al din al-Afghani, Liang Qichao, Rabindranath Tagore and others--possessed insights into the true nature of Western nations' motivations in Asia. They saw the dependence by Eastern states on the West and knew nothing good would come of it. They saw that their own states were weak and predisposed to this manipulation because of aspects in their own cultures, say, favoring authoritarianism or the blandishments of religion. Theirs were not democracies. The populace did not take a personal interest in government, which was opaque and insular. The Enlightenment had caused western states to swing away from despotism toward participative democracy. There was no such parallel movement in the East. There doesn't appear to have been much scrabbling about in dusty archives by Mishra. He does not appear to have a working knowledge of either Arabic or Chinese, and, it seems, has relied exclusively on English-language sources.

21-ce

empire-post-colonial

history

...more

43 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Vuk Trifkovic.

Vuk Trifkovic

519 reviews

48 followers

Follow

May 19, 2013

Complex book to review, but when it all comes down - disappointing. Technically, the prose is not really as good as you might expect from an accomplished novellist and based on Mishra's excellent polemic essays - for example his exchange with Niall Ferguson.

The argument itself is not without merit but utterly, utterly blinkered. In his anti-colonialism, Mishra is very quick to analyse very selectively and ends up in contradiction. So on the one hand, we hear on the merits of Ottoman empire being an empire, to the extent where he almost blames 'those pesky Christians' in the Ottoman periphery for wanting to secede. If that is just a bit selective, then his qualification of the Armenian Genocide as being caused by "Armenians harassing Ottomans" is offensive.

Equally, his treatment of Communism is baffling - is it the anti-colonial power of Lenin, or is it just another aspect of the Western modernity? Finally, some of the statement are just out of touch - for instance the accusation that the war in Chechnia was conducted by the West, via its agent the Russian. Curiously, he left Bosnia out of that passage entirely - probably as it does not fit his narrative that the USA-led forces intervened directly on behalf of the Bosnian Muslims.

But even that is not really the issue. The core of my disappointment is the apparent intellectual poverty of the thinkers he puts on a piedestal. They reek of provincialism and utter lack of originality. They may be interesting because of the influences they had. But the content itself is uninventive and unilluminating, if not downright trite.

Mishra is far too intelligent not to realize the consequence of the thinking he outlines in his book. Indeed, in last two pages he outlines a very likely scenario that will play out. I fear that he is right. I just wish that someone of Mishra's intellect would not glorify the path to disaster merely on the basis that it will be disaster in which white colonialist will suffer too.

25 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Muhammad Ahmad.

Muhammad Ahmad

Author

3 books

171 followers

Follow

February 3, 2013

[My review of Pankaj's book was first published in Guernica magazine]

As tsar Alexander III sat down for an evening's entertainment at the St. Petersburg opera house in late 1887, he little knew that the performance would soon be upstaged by one much more dramatic. Shortly after the curtains rose, a slender, goateed man with azure eyes, dressed in a robe and turban, got up from a box nearby and proclaimed loudly: “I intend to say the evening prayer—Allah-u-Akbar!” The audience sat bemused and soldiers waited impatiently as the man proceeded, unperturbed, with his evening prayers. His sole companion, the Russian-born intellectual Abdurreshid Ibrahim, squirmed in fear of his life.

Jamal ud-Din al-Afghani was determined to recruit Russian support in his campaign against the British. Having failed to secure an audience with the tsar, he had decided to use his daring as a calling card. The tsar’s curiosity was finally piqued and Afghani had his hearing.

This could be a scene out of Tolstoy or Lermontov; but so extraordinary a figure was Jamal ud-Din al-Afghani (1838-97), the peripatetic Muslim thinker and revolutionary, that inserting him into fiction would strain credulity. So, renowned essayist and novelist Pankaj Mishra has opted for historical essay and intellectual biography to profile the lives of Afghani and other equally remarkable figures in his new book From the Ruins of Empire: The intellectuals who remade Asia.

The book is a refreshing break from lachrymose histories of the East’s victimhood and laments about its past glories. It concerns a group of intellectuals who responded to the threat of western dominance with vigour and imagination. Together they engendered the intellectual currents that have shaped the last century of the region’s history.

Wild Man of Genius

The Iranian-born Jamal ud-Din al-Afghani’s long sojourn across Asia, Europe, and North Africa was animated by a search for dignity, self-strengthening, and self-determination. He was responding to the challenge of western modernity and European colonial domination. As Afghani saw it, an ossified Islam with a literalist interpretation of scripture was hindering Muslim progress. He was determined to reconcile Islam with rationality, and to develop a strategy that would leverage popular discontent to dislodge Western colons from Asia. The political vehicles he experimented with included Islamic reformism, ethnic nationalism, pan-Islamism, and, later, political violence (an idea he quickly abandoned after a disciple assassinated the Shah of Iran in 1896).

Described by English poet Wilfrid Blunt as a “wild man of genius,” Afghani’s strategies were in fact more visionary than wild. He preached syncretic nationalism in India, drawing on both Islamic and Hindu traditions. He advised the Afghan amir into confronting the Raj. He fomented Egypt’s first anti-British uprising. He inaugurated Iran’s consequential alliance between the clergy, intellectuals, and merchants. And he attempted to use the Ottoman Sultanate as the focus of a pan-Islamic challenge to Western imperialism. He was fêted by—and simultaneously antagonised—kings, khedives, amirs, sultans, shahs, and tsars. In the meantime, he conducted debates with Ernest Renan, confronted British colonial officials, participated in the Great Game, romanced a German lover, established journals and secret societies, and mentored revolutionaries across the region. His disciples ranged from the nationalist Saad Zaghlul to the Islamist Muhammad Abduh and Rashid Rida. During his stay in Paris in the early 1880s, he also wrote for a French Communist paper, anticipating the anti-imperialist Red-Green alliances of the coming centuries. (Rashid Rida would later emulate him in penning articles for Ho Chi Minh’s journal in Vietnam.)

Afghani’s influence has lived on through figures as diverse as Muhammad Iqbal, Ali Shariati, Abul Ala Maududi, and even Pakistan’s Imran Khan, who uses an Islamic idiom in the service of a reformist agenda. Egypt’s three dominant political trajectories of the past century—reformist nationalism, Islamist populism, and revolutionary violence—can all be traced to Afghani’s influence. His disciples played central roles in establishing both the Wafd Party and the Muslim Brotherhood. His ideas were later adopted and stripped of their rationalist content by Sayyid Qutb to turn them into a pretext for political violence. His acolytes also included the Egyptian Jewish playwright and journalist James Sanua, and the fin de siècle women’s rights activist Qasim Amin.

Waking Giants

China’s ascent to super-power status was anything but smooth; perhaps no one figure was more more significant in jumpstarting the somnolent empire’s progress than Liang Qichao (1873-1929), the second major intellectual profiled by Mishra. Like his mentor Kang Youwei, he was a monarchist steeped in Confucian tradition before embarking on an independent trajectory after being banished from a Manchu court in thrall to Western powers. His initial response to the West’s challenge was to use Occidental ideas to invigorate traditional thinking. He went so far as to embrace Social Darwinist views about the hierarchy of races.

But Liang’s admiration for the West proved ephemeral, dissipating after a fundraising tour of the United States. Where Alexis de Tocqueville had been impressed by the vibrancy of American democracy, Liang was horrified by its gross inequalities, oligarchic rule, and severe mistreatment of minorities. He consequently took a jaundiced view of democracy itself, despite having himself pioneered mass-politics in China. With his mentor Kang, he had organized examinees for imperial posts to petition the emperor to annul a humiliating treaty with Japan. Kang had also established publishing houses, libraries, and schools in order to create a Chinese “people.”

But creating a people had consequences. By early 20th century, Chinese nationalism had acquired a racialist Han character with an explicitly anti-Manchu orientation. Sun Yat-sen’s nationalist revolution in 1911 made Liang leery of disruptive change. Liang was dismayed to see the modernism that he had helped foster degrade into slavish aping of the West. The excesses of nationalists and Communists impressed upon him the enduring merits of Confucianism, with its universal precepts of spiritual freedom and social harmony.

In 1917, after arguing for China’s entry into the First World War as a means to garner international clout, Liang, like his countrymen, was shocked by its treatment at the Paris Peace Conference. The Great Powers conceded nothing. Like European Modernists, Liang was also shaken by the wasteland left by the war. If the disabused realism of his post-war writing seemed at times an echo of Thucydides, at other times it anticipated structural realists like John Mearsheimer. “In the world there is only power,” he wrote. “That the strong always rule the weak is in truth the first great universal rule of nature. Hence, if we wish to attain liberty, there is no other road: we can only seek first to be strong.”

China endured a nationalist revolution, a civil war, a Communist revolution, and much else before assuming its present status. In this most stable and prosperous phase, however, it seems remarkably like the strong, autocratic, modernizing state that Liang envisioned, and that unreconstructed imperialists had always feared. At a Hong Kong reception in 1889, Rudyard Kipling had wondered, “What will happen when China really wakes up?” What for Kipling was a nightmare was for his contemporary Liang an abiding dream. Modern China is a realization of both.

Thus Spake Tagore

Liang Qichao’s hard-nosed realism was no barrier to the strong bond he formed with the uncompromisingly idealistic Rabindranath Tagore. Welcoming him on a lecture tour of China in 1924, Liang greeted the Bengali sage by saying, “our old brother [India], ‘affectionate and missing’ for more than a thousand years, is now coming to call on his little brother [China].” But by that time opinion had shifted sharply in China. A newer generation of modernists wanted to sever all connection with the past. Tagore’s warnings against uncritical emulation of the West met with a sceptical audience.

There was nothing inevitable about Tagore’s disillusionment with the West. He was the scion of a liberal Anglophile family whose patriarchs had participated in the British opium trade. British Orientalists introduced him to the indigenous literary traditions that forged his philosophy. Unlike his friend Gandhi, Tagore admired the West. But the betrayal of the Paris Peace Conference and the grand imperial carve-up of Asia exhausted Tagore’s sympathies. In 1919 he wrote Romain Rolland: “there is hardly a corner in the vast continent of Asia where men have come to feel any real love for Europe.”

But Tagore’s disenchantment did not mean a retreat into defensive nativism. He was as likely to countenance imperialist cant issued from Japanese pan-Asianism as Western mission civilisatrice. He was never a hostage to his audience. At a 1930 dinner party in New York he accused his audience including Franklin Roosevelt, Sinclair Lewis, and Hans Morgenthau, of “exploit[ing] those who are helpless and humiliate[ing] those who are unfortunate with this gift.” He was equally disobliging when hosted by the Japanese Prime Minister in Tokyo: “The New Japan,” he told the gathered dignitaries, “is only an imitation of the West.”

Though anti-imperialist, Tagore was leery of radical nationalism. Once Japanese nationalists set it on an expansionist trajectory he vowed never to return, though he had earlier considered Japan as a model of indigenous modernization. Radical forces superseded him in India too which was finally fractured by the national egoism he had warned against. Tagore’s voice survived only in the national anthems of truncated India and Bangladesh. (His influence has also lived on through the experimental school he established in 1901; alumni include Amartya Sen and Satyajit Ray.)

Return of the Natives

The scope and ambition of From the Ruins of Empire would have overwhelmed a lesser writer. Mishra delivers with panache. He tackles the complex histories and politics of the formerly colonized realms with rigour and sensitivity. His sharply drawn characters are woven into a narrative that is riveting and insightful. But it is Mishra’s unerring political instincts, unencumbered by ideology, that make this book such a compelling read. Few writers possess the facility with which Mishra moves from acute journalistic observation to confident historical analysis.

In the colonized lands Mishra writes of, there were few who suffered illusions about European power. But some did put stock in the promise of America. When, in anticipation of the Paris Peace Conference, Wilson issued high-minded proclamations about national self-determination, everyone from Saad Zaghlul and Liang Qichao to Ho Chi Minh flocked to Paris to petition for the rights of their respective nations. All were disappointed. The humiliation that representatives from Asia and Africa suffered stung everyone. Little had they known Wilson was responding mainly to the Bolshevik threat; his promises of self-determination were aimed at an exclusively European audience. The idealists were disabused and the nationalists emboldened. Independence would not be granted; it would have to be seized.

Intuitive in retrospect, this idea was slow to gain wider purchase. The colonizers had easily crushed earlier insurrections, which lacked a unifying idea to lend coherence. But the seminal interventions of Afghani, Liang, and Tagore turned the vague ressentiment of the colonized into clearly articulated national projects. Colonialism finally ran up against mass politics and was defeated. None of this would have happened without the supra-national conversations inaugurated by these remarkable individuals.

The West has since built itself a reassuring mythology in which, moved by the moral example of individuals like Gandhi, it graciously bestowed independence upon its former possessions. But the one factor more than any other that precipitated the Empire’s exit from Asia wasn’t Gandhian satyagraha, but Japan’s spectacular early victories over the colonial powers. Beginning on 8 December 1941, it took Japan just ninety days to take British, U.S., Dutch, and French possessions across East Asia, advancing all the way to the borders of British India. “There are few examples in history,” writes Mishra, “of such dramatic humiliation of established powers.” If, according to viceroy of India Lord Curzon, the Japanese victory over Russia at the Battle of Tsushima had been a “thunderclap” which reverberated “through the whispering galleries of the East,” then Pearl Harbor was the storm that raised these voices to a roar. Japan was defeated in the end, but the nationalist fires it had kindled—mostly to advance its own imperial interests—could no longer be extinguished. The war sapped Western will and made decolonization inevitable.

Western power is still in decline, but Western perceptions of power remain oddly sanguine. From American presidential candidates’ strident statements against China during the 2012 election campaign to the superfluous French measures to exclude Turkey from the EU, it seems Atlantic powers fail to grasp that America and Europe need China and Turkey just as much as they are needed by them. During Israel’s November 2012 attack on Gaza, Egyptian and Turkish diplomatic initiatives made America all but irrelevant to the peace-making.

Straitjacketed by the imperatives of domestic politics, the West has been unable—or unwilling—to change course. Barack Obama had his Wilsonian moment in 2009, when he addressed the Muslim world from Cairo and moved many with his lofty rhetoric. But with his record of capitulations, his abject surrender to the Israeli right, and his international regime of extrajudicial killings, hope proved ephemeral. It disabused Arabs of the expectation that a foreign power could midwife change. Dignity demanded action. Rights had to be seized and agency reclaimed.

If an earlier generation had confronted and overthrown the autocratic managers of empire, a new generation is now uprooting the authoritarianism of the postcolonial regimes that had been hitherto justified as a nation-building imperative. The colonial legacy is finally being rolled back. But the sequence of events is not conforming to any known script. It is toppling dictatorships both pro- and anti-Western. The bogeyman of Islamism has served an ecumenical purpose, invoked by left and right alike. But if there is a common thread uniting the myriad forces of the Arab uprisings, it is not the promise of an Islamic resurgence. It is a search for dignity, social justice, and self-determination. The revolutions have been creative and resolute, improvising means but never ceding agency. They have even instrumentalized Western power at times but conceded nothing in return.

It is too early to predict how the Arab Spring will fully play out. But one thing is clear: external bogeymen will no longer stifle citizens’ demands for internal reform. The quality of these reforms will inevitably rest on the character of the ideas that inspire them. Here, however, Mishra is pessimistic. He notes that ideas with the capacity to inspire have been few and far between. Asia may be rebounding, he writes, but its success conceals “an immense intellectual failure.” He laments “no convincingly universalist response exists today to Western ideas of politics and economy, even though these seem increasingly febrile and dangerously unsuitable in large parts of the world.” This, however, is both a peril and an opportunity for the activists of the 21st century’s first great insurrection.

In the St. Petersburg opera house, Afghani failed to induce the tsar to confront the British. Still, through words and deeds, he continued fomenting uprisings from Egypt to Persia to Afghanistan. His companion, Abdurreshid Ibrahim, later participated in the Libyan uprising against Italian rule. He also joined Egyptian and Indian exiles in Tokyo to forge an alliance with the Japanese in a pan-Asianist front against Western imperialism. Their successes were ephemeral, but the ideas endured. In the end there was the word–and it is resonating still.

afghanistan

colonialism

culture

...more

16 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Omar Ali.

Omar Ali

224 reviews

217 followers

Follow

December 23, 2017

Pankaj Mishra's book is an unusually vapid and sophomoric work, carefully packaged to massage the prejudices of his liberal audience, but otherwise completely unoriginal and pedestrian. If you want to see how tendentious fakery is done by a professional, borrow it from a library. Dont buy it, you will only encourage him.

My rolling comments while reading the book are at http://www.brownpundits.com/2017/12/1...

A couple of excerpts from that overly long rant:

Spoiler Alert. since the “review” is really a very long rolling rant, written as I read the book, some people may just want to know this one fact: this books is NOT about the intellectuals who remade Asia. That book would have to start with people like Aizawa in Japan, the first Asian nation to be “remade”, but that is one nation and one set of thinkers you will not find in this book. Why? because this book is not about Asia, its history or its renaissance, it is about post-liberal virtue signaling. ..

On page 18 he says:

"the word Islam, describing the range of Muslim beliefs and practices, was not used before the 19th century. "

WTF?

This is then negated on the very next page by Mishra himself. The only explanation for this little nugget is that Pankaj knows his audience and will miss no opportunity to slide in some politically correct red meat for his audience. There is a vague sense “out there” in liberal academia that Islam is unfairly maligned as monolithic and even that the label itself may be “Islamophobic”. Pankaj wants to let people know that he has no such incorrect beliefs. It is a noble impulse and it recurs. A lot.

Pankaj’s summary of colonial history is boilerplate and unimaginative. He really has nothing new to reveal here. But he does seem to think (and, somewhat surprisingly, most of his reviewers seem to agree) that he is revealing new information and (to quote Hamid Dabbashi)”jolting our historical imagination and placing it on the right though deeply repressed axis. ”

This is very surprising. Are we to believe that Hamid Dabashi, a professor at Columbia, did not know this very basic outline of colonial history and had “deeply repressed it”? Anyone with any interest in history would know all this in much greater detail already. The only thing “new” here (and even that is not new any more) is a certain background hum of “postcolonial snark” (a certain feeling of superiority based on supposed/implied willingness to defy “colonial stereotypes” and Western imperialism and its promoters). ..

I think the key is to realize that Pankaj is crafting a shared (shared with his intended audience) anti-colonial pose/fantasy (mainly anti-British, he seems completely untroubled by the Russian empire in Asia, which is also very telling) and is following Afghani around from one half-baked idea to the next. Meanwhile, the actual 19th century world carried on, little affected by Afghani then and little affected by him now (though he has been adopted as a mascot by diverse Islamist groups, he is not a major source of their ideology or practice). Afghani’s tomb in Kabul meanwhile has been repaired with American “war on terror” funds. Oh the humanity!

My point is this: when Pankaj says

“It is impossible to imagine, for instance, that the recent protests and

revolutions in the Arab world would have been possible without the intellectual and political foundations laid by Al-Afghani’s assimilation of Western ideas and his rethinking of Muslim tradition”

He is relying on his audience being ignorant of the actual intellectual and political foundations of the various Islamist movements fighting in the Arab world today. The “assimilation of Western ideas and rethinking of Muslim tradition” are less a feature of contemporary Arab Islamism and more a thing that Pankaj would like them to have. (that the structure or methods of these movements are in many ways modern, hence to a large extent Western in origin, is not the same thing as consciously assimilating Western ideas and rethinking Muslim tradition).

13 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Martha.

Martha

206 reviews

7 followers

Follow

March 6, 2017

Outstanding. I've recently discovered this author, Pankaj Mishra. Maybe I spend too much time under my rock, but I think he should be much more widely known for his broad knowledge of history and deep understanding of the interaction between western and eastern philosophy and religion and the perspective he brings to it of someone who grew up struggling with both worlds.

If George W. Bush wants to know, as I believe he said, why "they hate us," he need only read this book. The relentless greed and vicious racism, the wars and exploitation, the broken promises and double dealing that the western colonizers practiced throughout Asia from the beginning of their dealings there were observed and absorbed by the boys and young men who grew up to be Gandhi, Nehru, Chiang Kai-shek, Mao Zedong, Ho Chi Minh, and through the generations to Ayatollah Khomeini and Osama bin Laden.

"The western world is scarcely aware of this overwhelming feeling of humiliation that is experienced by most of the world's population." If you want to know how we got where we are now, it's a direct line.

Mishra ranges through Japan, China, Korea, Viet Nam, India, Afghanistan, Persia, Egypt, and the Ottoman Empire from the late 1800s to the present discussing the lives and writings of the men who began to grapple with how Asia was to become "modern" and still somehow remain Asia.

"The fundamental challenge for the first generation of modern Asian intellectuals: how to reconcile themselves and others to the dwindling of their civilization through internal decay and Westernization while regaining parity and dignity in the eyes of the white rulers of the world."

Mishra knows so much history and can make so many cogent connections among time, space, and people; the writer he reminds me most of is the late Tony Judt, great explicator of modern European history. They would have made wonderful collaborators.

Mishra's latest book, just out, is Age of Anger, which brings this up to the present day. My husband's reading it now, and I'm fixing to as well as soon as he lets loose of it.

2017

reviews

social-commentary

...more

10 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Randal Samstag.

Randal Samstag

92 reviews

466 followers

Follow

May 6, 2019

Mishra’s book is the antidote to conventional stories of how the “third world” could “develop” if it only would pursue a Western model of social organization, be it capitalist or socialist. As a reviewer said here, this is the answer to George W Bush’s question, “Why do they hate us?” If you had never heard the name, Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, as I had not, you really need to read Mishra’s book. If you thought Why Nations Fail was a great book, you need to read Mishra’s book to find out why it is not. If you ever thought that America (or Europe) ever was great, you need to read Mishra’s book. Really, you need to read Mishra’s book.

10 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Jeff.

Jeff

313 reviews

22 followers

Follow

December 14, 2012

Pankaj Mishra is a journalist and novelist with an articulate prose style. His work has progressed from stories about travel in his native india to a novel (The Romantics), but his new book about key figures in Asia's transition from colonial conquests to modern nations is one of the most informative books i've encountered in a long time. i read it out of an interest in Asian history, but frankly, i think i learned more about the dynamics of contemporary global politics from the process. Why is today's Middle East so viciously hostile to "the West" (that is, Europe and the USA)? Why do China and india lead the world in certain areas, yet struggle with poverty? So many aspects of our current political reality have their origins in the European (i.e. British and French) colonialism and imperialism of the 19th century. Mishra himself admits at the end of the book that when he started out he was surprised by "how much he didn't know." That is how i felt by the time i was 20 pages into this book. A really informative, carefully constructed study - if i could, i'd make it required reading for all the members of Congress and the Pentagon: maybe it would give them a clue about why, when we took over iraq, we were not welcomed as "liberators," and why our struggle in Afghanistan will always be in vain.

8 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Marks54.

Marks54

1,426 reviews

1,177 followers

Follow

March 17, 2017

This book presents an intellectual history of global decolonization. The book is structured around a series of intellectual biographies of early Asian critical writers on how to best respond to the forcible intrusion and disruption brought about by the entry of European nations into Asian politics and culture. The temporal focus is on the 19th and 20th centuries. The biographies that are the focus of the book are generally ordered around the religious context of the three areas: the Middle East, South Asia, and China/Japan/Korea. The author is very thoughtful and appears to have read everything ever written on colonialism and post-colonialism. The stories in the biographies are well done and show how each author started out with some positions and then had to adjust his positions on the basis of relations with other writers. All of the writers start with one of a few positions, including learning from European colonializers. Then they watch as their ideas get put into practice among the crowds and then further adjust their thinking based on experience.