Woodward Missed Everything That Matters About the Trump Presidency

The alleged killing of a Washington Post columnist on the orders of the Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, has triggered many rethinks—and not least a rethinking of the lavishly flattering journalism that hailed the crown prince’s rise to supreme power.

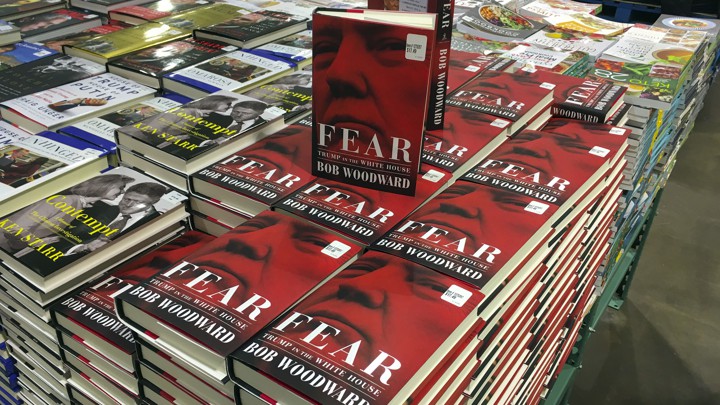

Among the biggest media boosters of the Saudi crown prince was Bob Woodward in his new book, Fear. Woodward observed that a National Security Council staffer, Derek Harvey, believed that “MBS was the future. MBS saw that transformative change in Saudi Arabia was the only path to survival for the Kingdom.” This is but one of the encomia to MbS in Woodward’s pages—all of them traceable much less to Woodward’s feelings about MbS than to Woodward’s apparent indebtedness to Harvey.

Woodward doesn’t publicly identify his sources, but much of his account of the inner workings of the National Security Council in the first six months of the Trump administration is relayed from Harvey’s perspective. (Harvey, a Michael Flynn appointee, would be fired by H. R. McMaster in July 2017. Harvey now works on the staff of Devin Nunes, the chair of the House Intelligence Committee.) No person in Woodward’s book is more lavishly praised than Harvey:

One of the premier fact-driven intelligence analysts in the U.S. government … a soft-spoken, driven legend … In some circles he was referred to as “The Grenade” because of his ability and willingness to explode conventional wisdom.

More valuable than such compliments is Woodward’s endorsement of Harvey’s big project: his determination, backed by Donald Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, to forge a region-transforming partnership against Iran in alliance with the Saudi crown prince. Harvey, with Kushner’s support, urged Trump to select a Saudi-led summit as the destination for his first foreign trip, in May 2017.

Harvey believed the summit had reset the relationships in a dramatic way, a home run—sending a strategic message to Iran, the principal adversary. The Saudis, the Gulf Cooperation Council countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia) and Israel were united. The Obama approach of straddling was over.

As for the big gamble on MbS, that, too—in Woodward’s account of Harvey’s thoughts—had culminated in a tremendous win. The section on the summit concludes triumphantly: “The next month Saudi king Salman at age 81 appointed MBS, age 31, the new crown prince and next in line to lead the Kingdom perhaps for decades to come.”

Even at the time, it was already clear that Harvey’s assessment was delusional. The Persian Gulf states were emphatically not united: Barely two weeks after the supposedly epochal Saudi Arabia summit, on June 5, 2017, Saudi Arabia joined Bahrain, the UAE, and Egypt to sever all diplomatic and travel links with Qatar, pushing the largely Sunni-majority states of the Persian Gulf to the verge of war. The Trump administration stumbled all over itself in response to that crisis. Trump threw his full personal backing behind Saudi Arabia and the UAE in a series of emphatic tweets, thwarting attempts by Secretary of State Rex Tillerson to broker peace with Qatar, the site of a crucially important U.S. military base.

MORE BY DAVID FRUM

By November 2017, the crown prince would organize the extrajudicial arrest of perhaps 500 Saudis. Some were subjected to physical abuse, The New York Times reported, in an effort to force them to disgorge assets to the regime. MbS, for his part, spent $300 million on the world’s most expensive private home in the suburbs of Paris, $500 million on a yacht, and $450 million on a Leonardo da Vinci painting over the past several years. MbS was the driving force behind Saudi Arabia’s proxy war against Iran in Yemen, a war that Saudi Arabia is losing—and that is leaving behind one of the greatest refugee crises on Earth, in one of the most destitute places on Earth.

Become a member.

Join The Masthead, our new membership program, and get exclusive content—while supporting The Atlantic's future.

More MbS recklessness would follow: a severing of relations with Canada in August 2018 to protest a tweet about a human-rights case in Saudi Arabia, and now, of course, the apparent torture and murder of Jamal Khashoggi. At some point along the way, it must have occurred to Woodward: Perhaps Harvey and Kushner had misjudged? Yet that obvious possibility leaves no imprint on the narrative.

Every book written about current affairs risks being outpaced. Seldom has that been more true than during the helter-skelter Trump years. I’ve struggled with this problem myself, and well appreciate how difficult it is. The uniquely powerful impact of Woodward’s reporting, however, magnifies the consequence of those difficulties in his case.

Fear is likely to remain the single most read book about the Trump presidency for some considerable time. Any misjudgments are disproportionately likely to mislead public understanding. The MbS instance is only one of a great many such misjudgments in Fear.

Fear either ignores—or outright denies—the most serious concerns about the Trump presidency. Its slam-bang quotes hit hard, but they also consistently miss the most important targets. The ultimate Trump tell-all actually tells disturbingly little of what the American public most needs to know. Now that the public has absorbed Woodward’s revelations, it is time to undo the harm done by Woodward’s methods.

Woodward sees himself as just a reporter, collecting facts and offering them to readers. As he told an interviewer in March, “My job is not to take sides. I think it’s important to send the message to people and to act and be as careful and neutral as possible.”

This commitment to neutrality promises fairness. Its effect, however, can be to absolve the journalist of responsibility. Woodward cares a great deal about accuracy: If he is describing a conversation, he will check the memories of as many participants as will speak to him, checking and double-checking that he has reproduced as nearly as possible what happened in the room. But there he stops. It’s not his job, as he seems to see it, to check what happened in the room against what happened in the external world. His disavowal of any point of view of his own effectively resigns the book to the control of his sources and their points of view. Which is how a book about Trump’s Washington can end up doing the work of advocacy for the crown prince of Saudi Arabia’s high-risk authoritarianism.

A Woodward book is composed of a series of transactions. The foundational transaction in Fear was initiated in the very first weeks after Trump’s lucky-bounce Electoral College election.

In those weeks, information began to leak from the intelligence services about the connections between Trump’s team and Russia. Startled and wrong-footed, Team Trump’s fumbling early responses to the revelations only worsened the situation.

Trump’s staff needed an external validator, a person of unimpeachable integrity and prestige who would endorse their view of themselves as victims of an out-of-control FBI. And on January 15, 2017, that’s exactly the service Woodward performed for them. That day, he appeared on Fox News Sunday to deliver a scathing attack on the Steele dossier, which had been published by BuzzFeed on January 10, 2017. Woodward tells the story in the pages of Fear, so let’s hear his own words:

I said, “I’ve lived in this world for 45 years where you get things and people make allegations. That is a garbage document. It never should have been presented as part of an intelligence briefing. Trump’s right to be upset about that.” The intelligence officials, “who are terrific and have done great work, made a mistake here, and when people make mistakes they should apologize.” I said the normal route for such information, as in past administrations, was passing it to the incoming White House counsel. Let the new president’s lawyer handle the hot potato.Later that afternoon Trump tweeted: “Thank you to Bob Woodward who said, ‘That is a garbage document … it never should have been presented … Trump’s right to be upset (angry) … ”I was not delighted to appear to have taken sides, but I felt strongly that such a document, even in an abbreviated form, really was “garbage” and should have been handled differently.The episode played a big role in launching Trump’s war with the intelligence world, especially the FBI and Comey.

At the time Woodward spoke those words, he was already engaged in intense negotiations for access to the new administration.

On January 3, 2017, Woodward was spotted entering Trump Tower in New York City. The Associated Press reported that Woodward explained that he was “visiting a couple of people.” The report continued:

Pressed for details, he said he agreed not to disclose details about the meetings.Woodward said, ‘‘There’s no secrecy about it. It’s just that I’m doing my work.’’ He added, ‘‘It’s something I’m working on long term. I hope you’ll understand.’’

Fear made headlines with its revelations of anti-Trump grumblings by senior officials within Trump’s own White House. But it’s better understood as a work that originated as a pro-Trump book—and despite its spectacular anecdotes, as a book whose pro-Trump bias still provides its architecture and rationale.

Woodward’s accounts of the transition rest heavily on the perspective of Michael Flynn, the national-security adviser designate—and perhaps not coincidentally, Woodward offers the most exculpatory possible account of the backdoor dealings with Russia that would lead Flynn to plead guilty to lying to the FBI.

Why did Flynn plead guilty? … Flynn told associates that his legal bills were astronomical, as were his son’s, who was also being investigated. A one-count guilty plea for lying seemed the only way out. His statement said, “I accept full responsibility for my actions,” and said he now had an “agreement to cooperate.” He denied that he had committed “treason,” an apparent denial that he had colluded with the Russians.

Woodward does report that Flynn accepted money from Vladimir Putin’s regime. He does not mention that Flynn violated Pentagon rules against retired generals accepting payment from foreign governments. Instead, he quotes uncritically Flynn’s own explanation of his actions:

Flynn was being widely criticized for going to Russia to speak for $33,750 from the Russian state-owned television network in 2015. He said it was an opportunity and he got to meet Putin. “Anyone would go,” he said.

After Flynn’s exit, the book repeatedly relays the perspectives of six other men: Steve Bannon (Trump’s former chief political strategist), Gary Cohn (the former chief White House economic adviser), John Dowd (the president’s former lawyer), Senator Lindsey Graham, Rob Porter (the former staff secretary), and Reince Priebus (the former chief of staff). Their internal battles provide the drama of Fear; the story is told from their points of view. The result is a weirdly lopsided book. Trump is leading the most unethical White House and most corrupt administration in modern U.S. history, arguably in all of U.S. history. But that does not rate attention from Woodward, perhaps because those scandals do not perturb his sources. Woodward’s sources care about Trump’s chaos and disorder—and so that becomes the gravamen of Woodward’s critique.

“I can deal with losing a battle in the White House as long as we follow proper procedure and protocol. But when two guys get to walk in your office at 6:30 at night and schedule a meeting that the chief of staff and no one knows about, I can’t work in that environment.” So grumbles the important Woodward source Gary Cohn after losing an argument over trade to the administration protectionists Wilbur Ross, the secretary of commerce, and Peter Navarro. Much of Fear is consumed by the struggles of Cohn to preserve the world trading system by enforcing rational processes. Cohn drew on help from Rob Porter, another important Woodward source.

But when Trump acted to harm norms and institutions that Woodward’s sources care about less than they care about trade, Woodward’s book goes silent.

Ross, tangled in allegations of scandal of almost Teapot Dome dimensions, receives only the most glancing references in Fear, and then only to the degree that his views on trade contradicted those of Cohn. The disgraced former EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt appears in only a single episode; the secretive Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke not at all.

Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price and Veterans Affairs Secretary David Shulkin were forced out over expense abuses, but their stories do not register with Woodward—neither is mentioned. Neither does Woodward dwell on the weird, abortive appointment of Anthony Scaramucci as communications director, or the nomination of the former presidential physician Ronny Jackson to replace Shulkin.

Jared Kushner’s financial issues go unmentioned, as do his many misstatements on his disclosure and security-clearance forms. So, too, do Ivanka Trump’s trademark approvals from China.

No president since Andrew Johnson has so aggressively deployed racial provocation as a political strategy. Woodward has a little more to say on that subject than about corruption, perhaps because Cohn did not appreciate Trump’s racism. But not much more. And zero about Trump’s abuse of women. Although The Wall Street Journal reported the Stormy Daniels nondisclosure agreement as early as January 2018, her name appears nowhere in Fear.

To the very last page of Fear, Woodward disparages the significance of the Trump-Russia connection. Trump’s blurting of high-level U.S. secrets to Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov in the Oval Office? Not here. Trump’s no-minutes-taken conversations with Putin at the G20 meeting in Hamburg in July 2017? Nope. The accelerating exposure of the falsity of the various accounts of the Trump Tower meeting? On that, Woodward acts as a stenographer for the Trump defense, as offered by Trump’s then-lawyer John Dowd.

“You guys tell me where the collusion is. And don’t give me that chickenshit meeting in June,” Dowd said, referring to Donald Trump Jr.’s meeting with a Russian lawyer in Trump Tower.“That’s a nothing. There’s no collusion. And the obstruction? It’s a joke. Obstruction’s a joke. Flynn? I mean, Yates and Comey didn’t think he lied.”

Dowd’s characterization goes un-rebutted by any other source, and Woodward doesn’t fact-check Dowd’s claims for his readers. Indeed, I count not a single instance in the whole book where a factual claim by a Woodward source is assessed or evaluated in any way. Woodward is scathing about Trump’s own lack of truthfulness. But if a Trump untruth is accepted and repeated by a Woodward source, Woodward will reproduce it in full and without qualm.

Almost all of the final 15 pages of Fear are filled by a sequence of lengthy monologues by Dowd. Woodward, by this point, seems to have been racing toward a deadline. The Dowd soliloquies are dumped almost directly into the text, without comment or qualification. In the middle of page 352, Dowd is pep-talking Trump, assuring him of his innocence, vowing to win the case, worried only about the risk of a Trump misstatement if the president were to disregard Dowd’s advice against speaking directly to Special Counsel Robert Mueller. The time is mid-March 2018.

Then there’s a section break—and wham, Dowd is gripped by total disillusionment and hovering on the verge of a resignation, a state of mind that fills the next and final four pages of the book to its much-quoted conclusion: “Trump had one overriding problem that Dowd knew but could not bring himself to say to the president: ‘You’re a fucking liar.’”

There’s no explanation of the leap from one mood to the other; it reads as if a crucial couple of pages of Woodward’s text were inadvertently sliced from the manuscript without anybody noticing.

This omission of a transition may only be due to carelessness, but the effect is serious. When sliced from context by news reports, Dowd’s words sound like a damning condemnation of Trump. But in context, they are meant by Dowd—and reproduced by Woodward—as a defense of Trump. What Dowd is saying is that the Russia story is bogus and that Trump is completely innocent of it. Trump’s only legal risk, Dowd is saying, is that he is so compulsively susceptible to exaggeration that he could entrap himself in perjury despite having done nothing substantively wrong. It is this exoneration that Woodward offers as his grand finale.

Fear paints a damning picture of Trump the human being. Who will soon forget Trump’s derisive comment that H. R. McMaster—whose life of service to the United States crimped his clothing budget—“dressed like a beer salesman”? Yet in the end it offers a remarkably forgiving assessment of Trump the president. The Trump presidency without the corruption, without the Russia entanglement, without the racism, without the abuse of women is hardly recognizable as the Trump presidency at all. There are worse offenses than messiness, after all.

Woodward approaches the Trump presidency as he has approached every other subject in his long and distinguished career. But the Trump presidency is something quite unlike anything anyone in Washington has seen before. Woodward’s access to the administration’s relatively normal figures—Cohn, Porter, Priebus, and their colleagues—actually erodes rather than enhances understanding of the administration’s actions. Their need to justify their own service to Trump compels them to minimize what Trump is and extenuate what he is doing. Woodward’s reliance upon them leads him to minimize and extenuate, too. If the only things we had to fear about the Trump administration were the stories told in Fear, Americans and the world could relax. Unfortunately, by relying on Trump’s enablers, America’s most legendary reporter has largely missed the biggest part of what they enabled.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

DAVID FRUM is a staff writer at The Atlantic and the author of Trumpocracy: The Corruption of the American Republic. In 2001 and 2002, he was a speechwriter for President George W. Bush.

No comments:

Post a Comment