Would You Kill for a Job?

Dec. 27, 2025,

A red and blue photo collage of Man-su from the film “No Other Choice”

By Jenny Odell

Ms. Odell is the author of “How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy.”

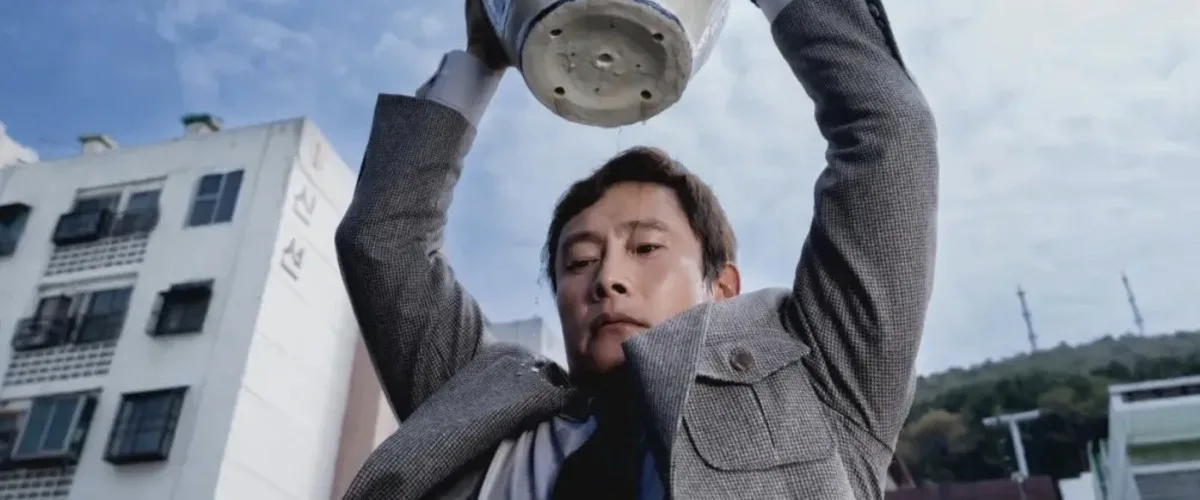

Park Chan-Wook’s latest film, “No Other Choice,” is an unflinching, bitingly funny portrayal of the moral depredation brought on by scarcity. Man-su, the film’s embattled protagonist, has lost his longtime job at a paper factory. He’s so desperate to get a new job in the same industry that he begins murdering his competitors.

The U.S. release of this Korean film resonates in a moment when America has its highest rate of unemployment since 2021 and the ratio of unemployed workers to job openings is on the rise. Not only that, but highly profitable corporations like Amazon and Salesforce are laying people off and slowing hiring, expecting that artificial intelligence will do that same work for less costs than an actual human.

Americans are worried. One 2025 Pew study found that a majority of us saw the risks of A.I. to society as high, while another found that about half of workers were anxious about the effects of A.I. use in the workplace, and roughly a third thought it would lead to fewer job opportunities for them.

All this suits the owners of companies just fine. After the pandemic years of a tight job market and workers getting paid more, the playing field is looking brutal. Sarah Thankam Mathews, in an article in The Cut about the “humiliation ritual” of applying for jobs, notes that a young person now may expect to change jobs 12 to 15 times in her life. Precarity stalks the jobs once thought of as safe, and the cutthroat atmosphere affects even those who still have a job.

In his book “Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It,” Cory Doctorow details how mass firings at tech companies like Google eroded worker power, including the ability to thwart the company’s own unscrupulous initiatives from within. The threat of firing acts “as a powerful disciplinary force on workers, changing their posture from ‘I won’t enshittify that product I missed my mother’s funeral to ship, and you can’t make me’ to ‘Whatever you say, boss.’”

Sign up for the Opinion Today newsletter Get expert analysis of the news and a guide to the big ideas shaping the world every weekday morning. Get it sent to your inbox.

Mr. Park, whose previous films include “Oldboy” and “Lady Vengeance,” is well suited to this tale of cruel circumstances, adapted from Donald Westlake’s 1997 novel “The Ax.” “After slaving for 25 years, they gave me 25 minutes to clear out,” Man-su says, running after the car of a line manager at Moon Paper, the company where he hopes to be hired.

Man-su’s victims, like their killer, have also been fired after corporate restructuring, and have attended similar workshops, like one where a cheery woman with a headset has former employees tap the sides of their heads and chant affirmations: “I am a good person!” and “In three months, I will be hired again!”

Scenes like these capture an essential dissonance at the heart of the working world. We want work to provide meaning and purpose — or at the very least, to provide us with the ability to support ourselves (ideally without compromising our deepest ethical values.) But seen from the other side, workers and their time are simply material inputs that can be squeezed and cut in any way that suits investors. The tension between these expectations sets the stage for rude awakenings, in which companies reveal just how much more they value efficiency over human lives.

It doesn’t exactly make for a respectful relationship. Early on in the film, a shot of Man-su hugging his family in front of his soon-to-be-unaffordable house fades directly into one of cardboard boxes being violently thrown into a hydrapulper at the paper factory. The same company that once promised Man-su that he’d have a job for life (as long as he didn’t join a union) has fired him without thought, throwing him away like so much recyclable material.

Chronic job insecurity undermines any chance of solidarity. It reduces the horizon of struggle to one of personal survival. For an individual trying to make ends meet, there is often “no other choice” but to accept self-abasement. Other people become objects blocking the way to freedom.

This view goes beyond the material damages of unemployment. It threatens aspects of the heart and soul. “No Other Choice” demonstrates the tragedy of a once-morally-intact character who so fully internalizes the ruthlessness of a system that he believes he has no other choice than to kill his fellow unemployed. “The end justifies the means,” recites the protagonist in Mr. Westlake’s “The Ax.” “Like the C.E.O.s, I have nothing to feel sorry for.”

At the end of the day, however, most of us are not C.E.O.s. And neither are we willing to be cardboard boxes for the hydrapulper. We are human beings with ideals that have proven curiously stubborn.

Even when workers are seen from the top as nothing but labor time, we workers — no matter what we do — must still make meaning inside our lives to survive. And despite the ongoing attempt to rid us of that desire, we still value and deserve things like stability and respect. The film’s title and recurring phrase invite us to ask what, in fact, the other choice would be.

For the companies, it’s true: There is no alternative to pleasing investors. But for us, there is a choice: not to succumb to a kind of Stockholm syndrome, absorbing the anti-human values of a game that benefits so very few. The people who actually do the work have a right to the conversation about what purposes work serves in our lives and in society, beyond the brute measure of efficiency.

Yet this is a choice that can only be imagined and accessed on a collective level. As a young worker tells Mathews for her article in The Cut, “If more of us stop accepting bad terms, we might see the strength we actually have, instead of being pitted against each other.” History provides countless versions of this lesson: The power to say no, to make the choice that is not presented, requires large groups of people to take on risk together, whether that’s in unions or through less formal means.

Adapting this old truth to the technological present is no easy task. And yet, the alternative is untenable. The current balance of power has people reconfiguring themselves to the ever-increasing speed of corporate whims. Our collective ability to decide what work should mean takes time and space, and this time and space can only be the fragile product of mutual commitment. It’s the image of the future that appears when we take off the blinders of individualism. Whatever we do, we should each reject the lie that all of this is inevitable. There is always another choice.

If we ignore collective action, our individual choices will be limited to short-term methods of staving off our own demise, all while being asked to celebrate the very technology that may alter our work beyond recognition or eliminate it entirely.

Once Man-su has killed his way to a position at Moon Paper, executives tell him that the paper plant has been fully automated, meaning that workers will have to be reduced. “If you don’t like it, you can say no,” one of them says. Everyone in the room laughs, including Man-su. “Not at all,” he says obsequiously. “How can you go against the times? But at any rate, you need one person to watch over it all, right?”

Man-su arrives at the factory, small and alone among the robots. He looks around, then pumps his arms in celebration; he’s won, for now. Despite being told by management that it’s no longer necessary, he performs his old task of hitting a wooden stick against a giant ream of paper, as robot arms punch at it in the background. In the final shot, the lights shut off one by one, until darkness overtakes Man-su.

If this is a victory, it is of a brief and Pyrrhic kind. He’s in fact won nothing, only bought himself some time. Were he to continue on this narrowing path, any windows onto possible resistance would get smaller and smaller. And soon enough, there would be no choices left at all.

More on Park Chan-wook

==

No Other Choice

Crime

Crime139 minutes ‧ R ‧ 2025

Brian Tallerico

2 days ago

4 min read

Park Chan-wook knows exactly where to put a camera. There is a scene in the middle of his newest, the hysterical and razor-sharp “No Other Choice,” in which Lee Byung-hun’s anti-hero Yoo Man-su is about to cross a line from which he cannot return. He points a gun wrapped in plastic in a hand covered in oven mitts at a sleeping man. He turns up the music before he shoots to hide the gunfire, but the man wakes up. Barely heard over the music, the two argue over how Man-su’s victim never listens to his wife, and that he’d be happier if he just took her advice. As a catchy tune fills the air and the two men bicker, his wife sneaks up behind Man-su, ready to knock him out before she hears his defenses of her. The sequence, including the slapstick physical altercation that follows, is a standalone work of art, a reminder of Park’s stunning ability with blocking, framing, pacing, and unpredictable plotting. The movie around this scene may be a few minutes too long, but it’s a minor complaint about a wickedly entertaining piece of work.

The director of “Decision to Leave” and “The Handmaiden” retells Donald Westlake’s 1997 thriller The Ax (already made once by Costas-Gavras in 2005) for an era dominated by conversations about workforce shrinkage in the age of A.I. It doesn’t seem coincidental that Park has made a film about a man who attempts to remove all of his competition at a time when stories about the extinction of the human worker in favor of an A.I. one make new headlines every week. It’s a deceptively clever movie, a pitch-black comedy that sometimes plays like a vicious episode of Looney Tunes but also hides commentary on how workers are being forced to go to extremes to stay alive when they’ve been given no other choice.

It opens in happier times for Man-su and his family, including a supportive wife, Lee Mi-ri (a fantastic Son Ye-jin), two beautiful children, Si-one and Ri-one, and two gorgeous dogs. As they celebrate their perfect lives outside of their perfect home, storm clouds appear on the horizon. The symbol becomes real when Man-su is downsized from his paper company, forced back into a brutal job market. Man-su realizes that the only way to beat the competition for the job he wants is for them to be unable to apply for it, so he puts in motion a series of plans to literally eliminate his competition.

What starts as relatively playful and almost silly, a tone enriched by Lee’s layered performance that mingles Man-su’s desperation, intelligence, and broken pride, eventually gets much darker. Let’s just say there comes a point for most viewers when they remember this is by the guy who made “Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance” and “Oldboy.” He’s not afraid to find humor and entertainment in the dark underbelly of mankind. And yet “No Other Choice” also feels like one of Park’s angriest films, a commentary on what happens when fragile masculinity is fractured by corporate greed. Something has to give.

Before he can even figure out what to do next, Man-su’s life is turned upside down. The dogs are at the relatives’, the house is on the market, and the family even has to cancel Netflix. Through all of this turmoil, Lee Byung-hun gives what appears likely to be the most underrated performance of 2025. The star of “Squid Game,” “The Good, the Bad, and the Weird,” and “I Saw the Devil” is at his career-best here, deftly walking a tightrope of likability, relatability, and morbid humor. He understands Yoo Man-su down to his bones, capturing a guy who is clearly very smart but also acting out of fear that everything he has worked for will disappear if he doesn’t do everything possible to hold onto it. There are so many ways this performance could have gone wrong—too desperate, too morbid, too slapstick—but Lee avoids all of the traps, working in unison with Park to give a perfectly calibrated performance.

And then there’s what fans of Park have come to expect, especially in recent works: breathtaking compositions. Collaborating with cinematographer Kim Woo-hyung, Park has made one of the most visually striking films of the year. Again, he knows where to put a camera.

There’s something so rewarding about going to a movie and giving yourself over to a master like Park Chan-wook, someone whom you trust through all the twists and turns of a film as tonally complex as “No Other Choice.” It’s so easy to see all of the places where this unique gem could have gone wrong, and so satisfying to see it only make good choices from beginning to end.

Share

Pin

Brian Tallerico

Brian Tallerico is the Managing Editor of RogerEbert.com, and also covers television, film, Blu-ray, and video games. He is also a writer for Vulture, The AV Club, The New York Times, and many more, and the President of the Chicago Film Critics Association.

No comments:

Post a Comment