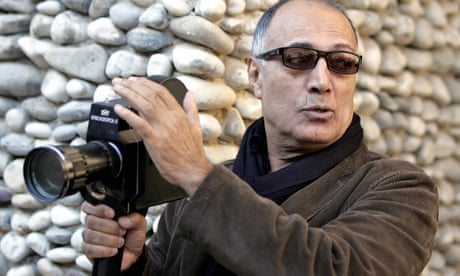

Abbas Kiarostami: sophisticated, self-possessed master of cinematic poetry

The Iranian auteur, who has died aged 76, specialised in a kind of realist-parable film-making that, despite its apparent simplicity, made him one of the great directors of our time

Abbas Kiarostami was a mysterious and delicate fabulist of human nature and human relations, a film-maker whose stories were somehow in, but not of, the real world. His movies didn’t render up their meaning easily; they were replete with meditative calm, sadness, reflection, but also dissent, obliquely stylised confrontation and emotional negotiation – as well as his own elusive kind of playful humour.

Kiarostami created a realist-parable cinema, often about the innocent world of children. This was an idiom which he may have developed to circumvent state interference and state censorship in his native Iran – and Kiarostami stayed notably loyal to his country, never exiling himself like Jafar Panahi and Mohammad Rassoulof, who were openly critical of its democracy and human rights record.

But that didn’t mean he avoided politics. His radically minimalist movie Ten (2002) was a film created from two fixed cameras in a car, showing a woman driving around the city, and simply talking to the people to whom she gives lifts, often women mistreated by men. It influenced Jafar Panahi’s much-admired recent film Taxi Tehran, but is actually bolder. The simple image of a woman at the wheel of a car is a political and feminist statement in the Middle East, where the idea of women driving is anathema to many.

Moreover, set against Kiarostami’s apparent simplicity was something highly sophisticated and self-aware about the act of film-making, and being a film-maker and public figure. An early trio of films, sometimes called the Koker trilogy because they are set around the village of Koker, are Where Is the Friend’s Home? (1987), Life and Nothing More… (1992) and Through the Olive Trees (1994); in the first, a young boy travels from Koker to a nearby village to return a schoolbook; in the second, that movie’s director sets out to discover if the two local boys he cast in the earlier work have survived Iran’s devastating 1990 earthquake and in the third, another fictional director examines an apparently minor scene in the second film, amplifying its importance. Reality and artifice are relentlessly questioned and opened out through a creative self-critique.

Kiarostami’s Close-Up (1990) was a startling, quasi-documentary account of a hoaxer who posed as Kiarostami’s great contemporary Mohsen Makhmalbaf, and The Wind Will Carry Us (1999) is about a man who visits a remote community with a camera crew, to document the rituals surrounding the imminent death of an old woman, apparently in retreat from family problems of his own.

Kiarostami’s films could be opaque, sometimes baffling and even exasperating; but always captivating, and utterly distinctive. And for me his masterpiece is the haunting Taste of Cherry, from 1997: it is movie possessed of a unique kind of moral beauty. A haggard-looking man in middle age is shown driving around the itinerant labour markets of Tehran, looking for someone to help him: someone who is good with a shovel, who can take orders and not ask questions.

What this man wants is to commit suicide, take an overdose of pills – and then he needs someone to bury him afterwards: a proposal that triggers astonishment and horror, as if he is asking strangers to be an accomplice in a kind of murder and a cover-up. Many try to talk him out of it, trying to persuade him of the simple pleasures of this fallen world – like the taste of a cherry.

The movie has some of Kiarostami’s unmistakable mannerisms: he is always fascinated by extended conversations in cars, conversations which happen in a space which is neither entirely public nor entirely private, and so can reveal more about the speaker than at first appears.

Car dialogue is also – as Kiarostami demonstrated in Ten – something which can be shot on location, in the real streets of a real city, but concealed from authorities who might decide they want to stop you filming.

Kiarostami also demonstrates one of his most distinctive auteur gestures: shooting one side of the conversation, a tic which is perplexing when you first encounter it. Yet maybe great directors are entitled to their eccentricities – things which ordinary mortals might consider mistakes. As Godard might skate through an entire scene in medium-shot, without conventional “coverage” of angles, and Ozu insist on direct sightlines into camera, so Kiarostami often weirdly abolished the “reverse shot” convention: he would show one character asking another a question and simply keep the camera trained on that character’s face, listening to the reply.

It’s an elegant oddity, part of Kiarostami’s defamiliarising technique. (Interestingly, its converse is the atypical moment when Kiarostami himself appears in front of the camera in his 2001 documentary ABC Africa, about children orphaned by Aids in Uganda, questioning white westerners who wish to adopt children.)

In Taste of Cherry, we never know why the principal character wants to take his own life, and neither he nor the movie ever invite sympathy or even sadness in the usual way. The point is that he does not merely wish for suicide, but utter self-annihilation. He does not want anyone to know he has killed himself: he wants simply to vanish, and the painful tragicomedy of trying to find someone to bury him – with all its legal illogicality – makes explicit the agony of this.

The film speaks profoundly to anyone who has suffered from depression: it is something to compare with Michael Henchard’s will at the end of Hardy’s Mayor of Casterbridge, in which he commands, in a kind of imperious agony, that no one must remember him.

Some of Kiarostami’s later films, shot outside Iran, I found to be less compelling. In Certified Copy (2010), shot in Italy, William Shimell and Juliette Binoche respectively play a celebrity author and the woman deputed to show him around the city – they begin a strange role-play game, acting out the parts of a bickering married couple.

Intriguing, if contrived and inert; and another variation on the theme of authenticity and fiction, which had interested Kiarostami since the days of the Koker trilogy. In Like Someone in Love (2012), a beautiful young Japanese escort is booked by an elderly academic: it is an intriguing movie, poised and self-possessed, but strangely unfinished, as if we are invited to imagine how such a situation might end.

At the beginning of The Wind Will Carry Us, we see the film-makers in their car driving through a sweeping but featureless landscape: a long and winding road, with a single tree. It is the kind of Beckettian scene in which Kiarostami sited his Taste of Cherry.

They have got lost looking for a village, which they think is supposed to be near a tree. The film-maker himself whimsically quotes a line of poetry, from Sohrab Sepehri’s The Token: “Near the tree is a wooded lane/Greener than the dreams of God…” It is a lyrical moment, gentle, unworldly, and yet with a sharp, ironic twist, like the jab of a needle. That was how Abbas Kiarostami’s own cinematic poetry worked.

No comments:

Post a Comment