Inside Kim Jong-un's Bloody Scramble to Kill Off His Family

While the world watches North Korea launch missiles, the very paranoid supreme leader has been busy eliminating anyone in his family who might knock him off the throne.

The video begins with no fanfare, no preamble. A lone figure, a young man in black, sits in front of a stark white backdrop. His hair is tousled. He fidgets. Light streams in from his right, but there is nothing to identify where he is or whom he's with.

He trains his eyes on the camera. "I'm from North Korea," he says in English. To prove it, he holds up a passport. Emblazoned on the front is a coat of arms featuring Mount Paektu, the sacred and still-active volcano in the far north of the Korean Peninsula, where the Kims trace an ancestry they claim gives the family its right to rule.

He looks off to his left, pausing to collect his thoughts. "My father has been killed a few days ago." Though the video was released on March 7 of this year, a month before I traveled to Pyongyang, the reference to the death indicates it was filmed weeks earlier. His voice is jumpy but composed. He does not mention which country he's in now, but he says he's safe.

There is one clue: an insignia at the top of the screen, in both English and Korean, that reads "Cheollima Civil Defense." A cheollima is a mythical winged horse capable of flying vast distances. It's a popular name in North Korea for everything from streets to fonts; a statue of one looms over downtown Pyongyang. It gives the name of the group, which seems to have helped this North Korean flee, a symbolic meaning that's at once serious and ironic.

He concludes by saying he hopes his situation will get better. The forty-one-second video then cuts to black.

The young man's name is Kim Han Sol. His father, Kim Jong Nam, was assassinated in an airport in Kuala Lumpur in February. The person widely believed responsible for issuing the order is Kim Jong Nam's half brother, the chairman of the Workers' Party of Korea, and the supreme leader of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea: Kim Jong Un.

At thirty-three, Kim Jong Un may be the world's youngest sitting dictator. But with his nuclear bombs and ballistic missiles, he's already among the most dangerous. On July Fourth, he gave what he gloated was an Independence Day "gift" to the "American bastards": the successful test launch of an intercontinental ballistic missile designed to obliterate American cities. Once his nuclear scientists get a warhead small enough to fit on the Hwasong-14 missile, he'll have a weapon capable of wreaking unimaginable destruction.

There is no question how important bombs and missiles are to the North Koreans. But the goal is not to carry out a first strike; with eighty thousand U. S. troops across Northeast Asia backed by a fleet of nuclear-powered weaponry, the North Koreans know such a move would be suicide. Kim Jong Un wants to prove his strength to the people he leads, to cause enough concern to force the international community to acknowledge the DPRK as a nuclear state, and to get the U. S. to the negotiating table—for aid and concessions, if not a peace treaty to finally, officially, end the Korean War.

While Kim stares down his enemies abroad, it's easy to forget that he's also fighting a battle from within his own borders: to survive at all costs. Like any autocratic leader, he's under constant pressure to maintain order and allegiance. But his youth and inexperience make staying in power that much more of a challenge, which in turn requires absolute control. Opposition must be eliminated. No one is safe, not even his own family.

Three weeks before his video appeared on YouTube, Kim Han Sol was in Macau with his teenage sister, Sol Hui, who'd just graduated from a nearby Anglican high school, and his mother, Ri Hye Kyong.

Macau was more home to them than Pyongyang. They'd moved to the former Portuguese colony, forty miles west of Hong Kong and now under Chinese control, in the early 2000s to seek refuge from North Korea. In Macau, the family lived under the protection of local police and could move around with relative ease. There they were safe.

On February 13, Kim Jong Nam was not with them. He was visiting Kuala Lumpur, a four-hour plane ride away, using a DPRK passport under the name Kim Chol—the North Korean equivalent of John Smith. There are few places in the world where a North Korean citizen can travel without diplomatic hassle. Malaysia is one.

That morning, Kim Jong Nam headed to Kuala Lumpur International Airport to catch a flight back to his family. Terminal 2 was bustling with travelers that day, from European backpackers in sandals to Malaysian women in ornately printed hijabs. It was the start of the Lunar New Year, and banners featuring baby chicks festooned the airport walls in celebration of the Year of the Rooster.

What happened next was captured on closed-circuit television later broadcast by a Japanese TV network. Kim Jong Nam, dressed in a T-shirt, jeans, and a summer blazer, strides into the terminal. He is alone and has no luggage, save for a black backpack slung over his shoulder. He stops briefly to check a flight display, then moves toward a line of check-in kiosks. A woman in white approaches him from behind. There is a brief tussle as she reaches around and wipes a cloth across his face. Another woman squeezes in and swipes his cheeks. Seconds later, both slip away, heading in opposite directions and disappearing into the crowd.

Kim lurches toward the information desk, where he interrupts an employee and gestures frantically at his eyes. Police accompany him to the airport's health clinic, though they don't appear to be in a hurry; Kim walks on his own. But a photograph taken minutes later shows him slumped in a chair in the clinic, arms outstretched, eyes glazed. He suffered a seizure, police would later say.

Kim died minutes later, in a hospital-bound ambulance. He was forty-five. Toxicology reports revealed that he was poisoned with the banned nerve agent VX, short for "venomous agent X." The dose was composed of two tasteless and odorless chemicals that are benign on their own but deadly once mixed—a possible explanation for the two face swipes. A single drop can kill within minutes; the substance can linger for up to half an hour, potentially exposing scores in a crowded space like an airport terminal. Developed during the cold war for military warfare, it is classified by the United Nations as a weapon of mass destruction. According to South Korea's Ministry of National Defense, VX is just one part of DPRK's chemical-weapons arsenal, the total size of which they estimate to be twenty-five hundred to five thousand metric tons.

February in North Korea is brutal. Fierce Siberian winds sweep across the country without respite or obstruction: Much of the habitable land in the country, which is about the size of Virginia, was denuded of trees decades ago.

Around the time of Kim Jong Nam's assassination, soldiers, teachers, factory workers, and traffic controllers were donning their warmest winter jackets to lay red flowers reminiscent of the late leader's namesake kimjongilia begonia at the foot of his statue on Mansu Hill. University students danced in public plazas to "Song of CNC"—an ode to computerization—jackets flapping as they twirled. Children ripped open gift packets to suck on the sweet candy inside. It was a time of celebration.

There are few places in the world where a North Korean citizen can travel without diplomatic hassle. Malaysia is one.

In the days after Kim Jong Nam's death, there was no word of it on North Korean state media. Without acknowledging the incident, Kim Jong Un presided over lavish festivities for a holiday honoring the February 16 birth of their father, Kim Jong Il, known as the Day of the Shining Star—an anniversary that is marked with the same mix of solemnity and festivity as Jesus' birth in the Bible Belt.

The Kims are everything, and everywhere, in North Korea. Bronze statues of Kim Jong Il and his father, Kim Il Sung, the first leader of the DPRK, loom over the city. Massive mosaics chart the mythology of their heroic feats. Their portraits cover the walls of every office, home, and school, and the loyalty badge pinned to the shirt over the heart of every adult in this nation of 24 million people.

Officially, North Korea calls itself a socialist state. In reality, it operates like an absolute monarchy. Kim Il Sung, the self-proclaimed guerrilla fighter and the DPRK's spiritual figurehead since its formation in 1948, was placed in power by the USSR at the outset of the cold war. He was the Soviets' man in Pyongyang, meant to install and maintain a communist regime. But Kim knew that ruling with a hammer and a sickle wouldn't be enough to command the devotion of a people who'd just survived nearly four decades of Japanese occupation, a period defined by systematic attempts to stamp out their language and culture. He and his political strategists drew heavily on Korean history and culture, in addition to mysticism, shamanism, and Christianity, to craft their singular version of Marxism-Leninism. They created a social order built around a cult of personality that was both familiar and new. Its guiding principle was called juche, a nationalistic ideology of self-reliance that inspired a sense of pride—and it was used to justify xenophobic, isolationist, totalitarian policies.

Like the founder of ancient Korea thousands of years before him, Kim also claimed ancestry in a lineage forged on Mount Paektu, the volcano that has held spiritual significance for Koreans for centuries. To be "descended" from the mountain meant that he—and his offspring—were godlike.

But mythology alone wasn't enough to keep order. For decades, the Kims have purged, exiled, and executed their enemies, often with scant or no proof of wrongdoing. People disappear all the time from North Korea, even at the highest levels of leadership. Assassinations are carried out in secret, and rarely acknowledged publicly. For North Koreans and foreigners alike, the best way to figure out who's in power and who's been purged is to keep an eye on state-media coverage of formal events. The names of officials are listed in order of seniority and importance; omissions often indicate that a person has been removed from power, or even executed.

Yoji Gomi, a Japanese journalist who covers North Korea, corresponded with Kim Jong Nam in the mid-2000s. Gomi told me Kim's assassination was "a message that North Korea will not tolerate any anti–North Korean views. It's a threat, a strong warning."

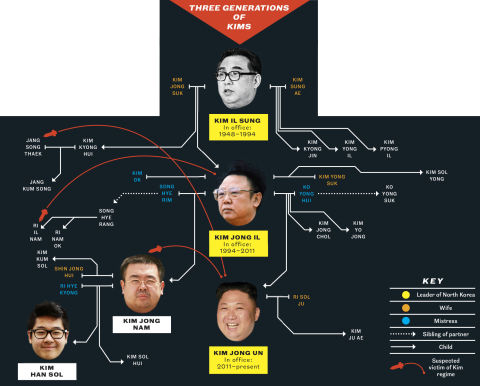

By the early 1970s, Kim Il Sung, then in his sixties, had been the DPRK's leader for more than two decades. Succession was on his mind, but it wasn't yet clear who among his relatives would inherit power.

Kim Jong Il, the president's elder son, proved his mettle by outmaneuvering Kims from what he called kyotkaji—"side branches"—in need of pruning. "In order to show his father that he was the most loyal, he mercilessly attacked and got rid of the associates he selected for reasons like having the wrong ideals," Hwang Jang Yop, a high-ranking party secretary who'd helped Kim Il Sung conceive juche, wrote in a memoir after he defected to South Korea in 1997.

First, Kim Jong Il engineered the relocation of his uncle, then a rising star in the ruling Workers' Party, to remote Jagang Province. Meanwhile, Kim's half brother, son of the president's second wife, was dispatched to a succession of North Korean embassies in Eastern Europe, where today he serves as ambassador to the Czech Republic, tethered to the regime but far from its center of power.

In 1974, Kim Jong Il, then the secretary of the party's Central Committee, was recognized internally as heir apparent. But it was a full twenty years before he took over, after Kim Il Sung died of a heart attack in 1994. The Dear Leader ascended to the head of state in what became the communist world's first hereditary transfer of power.

Kim Jong Nam was born into this world of court intrigue, in Pyongyang in 1971, to Kim Jong Il and his then-lover. Kim's birth, like his death, was never announced in state media. But he was doted on by his father: Diplomats were ordered to bring back expensive toys for his son, including diamond watches and gold-plated guns. Father and son were driven around in matching Cadillacs. According to a close Kim relative, the bill for the young Kim's lavish birthday parties ran more than $1 million, in a country where the yearly GDP at the time was less than $500 per person.

ADVERTISEMENT - CONTINUE READING BELOW

When Kim Jong Nam was three, his mother suffered a nervous breakdown that required medical care in Moscow. Kim joined her when he was eight, but he was so unaccustomed to life outside the royal palace that he urinated in his pants rather than use Russia's public toilets, recalled Song Hye Rang, his maternal aunt, in her 2000 memoir, Wisteria House. He was sent back to Pyongyang to live with his aunt and her children, Ri Il Nam and Ri Nam Ok. A 1981 family portrait (see page 97) shows a pudgy Kim Jong Nam in shorts and sneakers, his feet barely touching the floor, his father next to him, his aunt and two cousins standing over his shoulder. The cousins would later recall Jet-Skiing off Wonsan beach, watching foreign movies, and reading South Korean books with Kim—unimaginable, and illicit, luxuries for the average North Korean.

Kim Jong Il began grooming his eldest child for a future in politics, as his father had done with him, bringing him to his office. He dressed the boy in the military uniform of the marshal of the Korean People's Army. "This is where you'll be giving orders," Kim Jong Il said, according to his cousin.

But Kim Jong Nam soon had competition for the affections of the man he called Papa. Over the next two decades, Kim Jong Il had at least four more children: a daughter with his wife, and two boys and a girl with another mistress. Kim Jong Un was the younger of those two sons, born while Kim Jong Nam was off at boarding school in Geneva. As he'd done with his eldest son a decade earlier, the Dear Leader bedecked his youngest son in full military uniform. Kim Jong Il's sushi chef, a Japanese man who published a memoir in 2003 under the pen name Kenji Fujimoto, wrote that when he first met Kim Jong Un, then seven, the boy was outfitted like "a little general." A certain ruthlessness seemed to shine through even then: "He glared at me with a menacing look when we shook hands. I will never forget the look in his eyes, which seemed to be saying: 'This is one despicable Japanese guy.' "

This survival-of-the-fittest culture put the futures of Kim Jong Nam's close relatives in jeopardy. Some stayed in Pyongyang; others fled. In 1982, Ri Il Nam, one of the cousins who was raised with Kim Jong Nam, decided he wanted to live the "American dream," according to a tell-all memoir he published under an assumed name titled Taedong River Royal Family. He called the South Korean embassy in Switzerland, where he was then enrolled in school, asking for advice on how to seek asylum in the United States. The ambassador instead convinced him to defect to Seoul.

In his memoir, Ri recounted a circuitous, if relatively comfortable, route that took him from Switzerland to France, Belgium, Germany, and the Philippines, where he caught a flight to Seoul. Contrast that with the trials most North Korean defectors endure: Many don't have passports or travel permits and must bribe their way to the Chinese border. Because China has a policy of sending defectors back to North Korea, they must make their way on foot or by bus to a safe house or a refugee camp in a third country—Laos, or Vietnam, or Thailand—before they are able to reach South Korean embassies to seek asylum. The process can take years.

Ri lived quietly in Seoul under an assumed name and, thanks to plastic surgery, a new look. In 1995, broke and desperate for money, he agreed to call his aunt, Kim Jong Nam's mother, in Moscow in exchange for $5,000 from a Seoul-based magazine that wanted to air the conversation live.

It was Ri's own mother, Song Hye Rang, who picked up the phone. The call was the first time they had

spoken in fourteen years. The two spoke regularly for two months before Song decided to defect, too.

For decades, the Kims have purged, exiled, and executed their enemies, often with scant or no proof of wrongdoing.

"I had to choose," Song wrote in Wisteria House. "I could tell the leader everything and go back to Pyongyang, or take this chance to leave to the West." If she confessed, Kim Jong Il probably "would not punish me, but he would not allow me to leave Pyongyang," she wrote. "Even if there were plenty of books and I could take twelve baths a day and eat all kinds of delicacies, the residence was a prison to me."

At the time, most North Koreans would have considered one warm bath a month a luxury. It was a grim time to be an ordinary citizen in the DPRK. The country, already suffering from the loss of the safety net once provided by the Soviet Union, was in the throes of an unprecedented famine. For decades, most North Koreans had relied on the state to provide meals through a centralized rationing system. But by the late 1990s, the state had nothing left to feed its people. Half a million North Koreans starved to death, according to conservative estimates, in what became known as the "Arduous March." Meanwhile, in the royal palace, luxuries overflowed. Kim Jong Il, it was revealed, was the world's largest customer of Hennessy cognac in 1992 and 1993, reportedly racking up a yearly tab as high as $800,000.

In 1996, Ri published his memoir. He described growing up in the lavish household he called a "fancy prison." There, he said, the supreme leader presided over parties with strippers that devolved into orgies. When one wife threatened to report the bacchanalian festivities to Kim Il Sung, Ri wrote, her husband shot her to death in Kim Jong Il's presence.

Six months after the book's release, in February 1997, almost exactly twenty years to the day before Kim Jong Nam's death, Ri stepped out of his building's elevator and was shot in the head.

Ri's death spooked his sister, Ri Nam Ok, who'd fled North Korea in 1992. Before she left, she'd written a note for her uncle Kim Jong Il, whom she considered a father figure, begging him not to find her. Now with her brother dead, she sued to halt publication of her own memoir, The Golden Cage; the book was never released. "I was terrified of being found and taken back to North Korea, of being taken home in a bag," she wrote of her defection, according to a copy of the manuscript obtained by Esquire. "I would have preferred to be killed on the spot rather than suffer a life in the mines or the countryside." In a 1999 interview with South Korean newspaper JoongAng Ilbo, she further emphasized the fear that comes with belonging to the Kim dynasty: "Being exposed means death to our family." She has not spoken publicly since.

Defections occurred in Kim Jong Un's branch of the family as well. In 1998, his beloved aunt, Ko Yong Suk, who'd been dispatched to Europe to watch over him while he attended Liebefeld-Steinhölzli, a school outside Bern, Switzerland, fled with her husband to the United States, where today they live middle-class lives under new names with U. S. passports. Kim Jong Un was a teenager when she left, and some North Koreans suggest he was embittered by her abandonment. His heart hardened toward those who defected from the DPRK.

Born to different mothers a dozen years apart, Kim Jong Nam and Kim Jong Un grew up in separate palaces in Pyongyang. Kim Jong Nam claimed the two never met. Like his older brother, Kim Jong Un enrolled at the Swiss school under a false identity. A school official acknowledged the enrollment of a North Korean teen he described as "well-integrated, industrious, ambitious," and passionate about basketball. Every day, an embassy driver picked him up from school, and fellow students say they thought he was the driver's son. It was only when the young man made his international debut as the DPRK's heir apparent, in 2010, that they realized his quasi-royal provenance.

At the time, many assumed Kim Jong Nam, the eldest son, was being groomed to succeed his father. But he preferred partying to politicking. Gregarious and social, he began sneaking out to drink as soon as he hit puberty, his maternal aunt recalled in her memoir.

Kim simply was not suited for life in Pyongyang. "Kim Jong Nam was treated like a prince in North Korea," says Lee Sin Uck, a professor of political science at Dong-A University in South Korea. The two became friends when Kim visited Moscow, where Lee was in graduate school, in the late 1990s. "But he was bored and wanted to see the outside world."

The final straw came in 2001. Kim Jong Nam, by then a father of three—a son with his wife, and a son and daughter with his mistress—tried to visit Tokyo Disneyland using a fake Dominican passport under the name Pang Xiong: "Fat Bear" in Chinese. Kim, by then a portly figure in gold-rimmed glasses, was detained and sent back by Japanese immigration officials. The incident made international headlines. Kim and his father agreed he should move to Beijing, a two-hour flight from Pyongyang but far enough not to cause the regime further embarrassment. There, Kim's marriage soured, and he later moved with his mistress and their children, Han Sol and Sol Hui, to Macau.

With its crumbling, fading colonial buildings, its casinos and showgirls, Macau is a slice of old Europe in new Asia. On weekends, thousands of tourists take the hour-long ferry from Hong Kong to pack the narrow alleyways, see the cathedral, line up for the famous egg tarts, and drink vinho verde under the shade of palm trees in genteel courtyards of what is the most densely populated region in the world.

And to gamble. Sleepy by day but decadent by night, Macau—known as the Monte Carlo of the Orient, and the only place in China where casinos are allowed—is where Asia's nouveau riche go to indulge their vices. "Living Las Vegas in Asia," Kim wrote in a 2010 Facebook post, since taken down. Reporters assigned to trail him knew to lie in wait at the Wynn Macau or the Four Seasons, though he claimed in recent years to have given up gambling.

For a man raised in luxury, Kim Jong Nam led a simple life. He traveled by taxi rather than the chauffeured Mercedes-Benzes that today ferry the Kim family around Pyongyang. He dined at local Korean restaurants, sporadically treating friends to meals. He dressed in breezy weekend attire. But Kim was hard to miss, and not because of his gold necklaces, rings, and elaborate tattoos: He moved about with an official entourage of local police who, as he told Yoji Gomi, were providing either protection or surveillance. He was never sure which, but said he tolerated and appreciated their presence.

As a father, he gave Han Sol the ordinary childhood he never had. Instead of shuttling his son off to a Swiss boarding school under a false identity, leashed to North Korean diplomats charged with keeping an eye on him, Kim Jong Nam sent him to a local private school. There, Han Sol built a diverse group of friends, tested out new looks (ear piercings, dyed hair), and even explored Christianity. He started a Twitter account, posted photos to Facebook, and created a blog on which he listed Bruce Almighty and Katy Perry among his favorite cultural touchstones.

When Kim Jong Un's aunt left him, his heart hardened toward those who defected from the DPRK.

The equilibrium Kim Jong Nam had achieved for himself and his family began to shift when, in August 2008, his father had a stroke. As the leader recuperated out of the public eye, Jang Song Thaek, a Moscow- educated cadre who was married to the Dear Leader's beloved only sister, stepped in as de facto regent. With the future of the regime in question, Jang oversaw a campaign to groom his nephew Kim Jong Un to assume power.

Even if Kim Jong Nam hadn't expressed interest in politics in years, his half brother saw him as competition. In 2009, Kim Jong Un sent secret police to raid his vacation home and arrest his friends. After that, Kim Jong Nam told Gomi he avoided going back to North Korea. Lee, the professor at Dong-A University, says, "In a patriarchal society, when the first heir has been banished and the second or third son becomes the heir, the first son's existence becomes a threat. Considering the Paektu lineage, Kim Jong Nam was a threat."

When Kim Jong Un, then twenty-seven, assumed power in December 2011, following the death of Kim Jong Il from a heart attack (the same ailment that killed Kim Il Sung), he inherited an altogether more intense series of tensions than either of his predecessors did. The nation was economically troubled, with a per capita GDP estimated at 5 percent of that across the border in South Korea. Most North Koreans did not have reliable electricity or running water, much less computers or Internet access. Politically, Pyongyang had few friends abroad and was under growing scrutiny for its abysmal human-rights record. The country was, and still is, technically at war with the United States.

To inspire loyalty, Kim Jong Un modeled himself after his legendary grandfather, in looks and in manner. He wore the same Mao suits and straw hats Kim Il Sung wore at his age and introduced updated versions of the same economic policies. He revised the wording of a key national doctrine governing the daily life of North Koreans, known as "Ten Principles for the Establishment of the One-Ideology System," to require allegiance to those in the Mount Paektu lineage. He embarked on a campaign of terror, one that was even more far-reaching than those carried out by his father and grandfather, with an unprecedented spree of purges and executions, typically by firing squad, of those who opposed him or presented a threat. More than 140 party and military officials have been executed during Kim's rule, seared to death with flamethrowers or eviscerated by machine-gun fire, while their colleagues are forced to witness the gruesome, bloody killings, claims the Institute for National Security Strategy in Seoul, a government-funded research center affiliated with South Korea's National Intelligence Service. According to the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, commercial satellite images taken of North Korea in 2014 caught what appeared to be an execution by firing squad using antiaircraft machine guns.

Kim Jong Nam wrote to Gomi in January 2012, just days after his half brother took over, "Anyone with common sense would find it difficult to tolerate three generations of hereditary succession. I question how a young heir with two years of training is able to inherit absolute power that has lasted for thirty-seven years." Then, a miscalculation, or perhaps a willful denial: "Kim Jong Un is simply a symbolic figure."

Kim's criticism of the newly anointed leader did not sit well with Pyongyang. But he had a protector in Jang, the uncle who'd helped Kim Jong Un rise to power and was considered the second-most-powerful person in North Korea. Jang had high-ranking positions in the government, and he commanded a network of relatives and allies working at North Korea's missions and embassies abroad. He and his wife were Kim Jong Nam's main connections to Pyongyang.

That ended in December 2013, when Jang dramatically fell out of favor. Perhaps because he'd decided that his uncle had become too powerful, Kim Jong Un ordered Jang tried for treason and a host of other charges. Jang's execution by firing squad was made public, once again highlighting that no one, not even a close relative, was safe from the leader's wrath.

David Straub, a former U. S. diplomat and the LS-Sejong Fellow at the Sejong Institute, a think tank in South Korea, says he was "stunned" by the rashly vengeful way Jang's fall from grace was handled by North Korea. "This happened in such an atmosphere of paranoia and fear and overflowing adrenaline and testosterone," Straub says. "It shows that Kim Jong Un and the people around him put on a face of being completely confident but are under great psychological pressure. And that makes them take extreme action."

Kim Jong Nam soon found out that he, too, was on the regime's hit list. After an alleged assassination attempt, Kim pleaded with his half brother for a reprieve, the then-director of South Korea's National Intelligence Service told lawmakers two days after Kim's assassination. "Please withdraw the order to punish me and my family," he wrote in a letter reportedly intercepted by South Korean intelligence. "We have nowhere to go and nowhere to hide. Our only escape is suicide."

In late April, two months after Kim Jong Nam's death, I landed in Pyongyang. Abroad, headlines warned of impending war on the Korean Peninsula.

But in North Korea's capital, it was life as usual. The streets were calm. Farmers were preparing for the upcoming rice season. To the north, the eye-popping new neighborhood of Ryomyong Street, empty and imposing, flashed Technicolor like an amusement park on steroids. Just weeks earlier, the Marshal, as Kim Jong Un is known, himself presided over the inauguration of the new residential complex, constructed to reward his nuclear scientists.

I wanted to find out what people knew of the assassination. From years of reporting here, I knew to be cautious: North Koreans can be opinionated and snarky, but their openness does not extend to their leader and their country's political system. A strictly enforced law defines any criticism of the supreme leader as anti-state activity, punishable by hard labor or, for treason, execution by firing squad. The first time I traveled here, in 2008, our guide warned me not to destroy any North Korean newspapers. The Kims are featured or mentioned on every page, and so to crumple one up could be seen as defacing the leader's image. "Just lay the newspaper carefully on top of the wastebasket," she advised.

That warning came back to me when I heard the news that Otto Warmbier, a twenty-two-year-old University of Virginia student who was visiting North Korea in late 2015, had been arrested. Footage captured by hotel surveillance cameras shows him purportedly tearing down a poster written in Korean. He may not have known that it was a sign bearing Kim Jong Il's name, and therefore sacred. For his act of defacement, Warmbier was sentenced to fifteen years of hard labor before being released and returned to the U. S., in a coma, in June of this year. He died a few days later; his doctors said he had suffered massive brain damage while in the hands of the North Koreans.

Cautiously, I asked my guides, well-educated members of North Korea's elite, if they had heard about the death in Malaysia. They nodded, saying they had read about the death of "a citizen" by heart attack. Did they know who he was? I asked. Silence.

Kim's assassination may have gone unnoticed elsewhere in the world, too, if it hadn't been for an error on the part of the Malaysian police, who, according to Reuters, informed South Korea's embassy first—not North Korea's—about the death. The news was leaked to South Korean media, and it quickly spread around the world. What ensued was a bizarre diplomatic incident. Objecting to an autopsy, North Korean officials told the Malaysian government that the man was not, in fact, Kim Jong Nam. They demanded that the body be handed over. Police refused, and all but accused the North Koreans of trying to break into the morgue where it was held.

Kim Jong Un has demonstrated untrammeled ambition and ruthlessness that seem motivated by self-preservation at all costs.

Malaysian police arrested the two women spotted on security footage: one from Vietnam and the other from Indonesia, who independently claimed they'd been promised a hundred dollars to take part in a television-show prank. Shortly after, a North Korean chemist living in Kuala Lumpur was arrested but released due to lack of evidence. Four more suspects had already fled Malaysia and were safely back in Pyongyang by the time Interpol released a "red notice," the closest equivalent to an international warrant, calling for their capture.

It was discovered that three others who were wanted for questioning, including a diplomat and an employee of North Korea's flagship airline, were holed up at the North Korean embassy in Kuala Lumpur. When Malaysian police demanded that they be turned over, North Korea responded by barring Malaysians in Pyongyang from leaving the country. In retaliation, North Korean citizens were blocked from departing Malaysia.

At the end of March, a deal was reached: The three men wanted for questioning were cleared to depart Kuala Lumpur, leaving only the two women to face trial on murder charges. If convicted, they face the death penalty.

On the same day, it was announced that Kim Jong Nam's body would be returned to North Korea in exchange for the departure of nine Malaysians in Pyongyang. The half brother to the supreme leader would, after living abroad for more than a decade, finally return home.

In the six years he's been in power, Kim Jong Un has demonstrated untrammeled ambition and ruthlessness that seem motivated by self-preservation at all costs. Despite crippling sanctions that ensure his people's ongoing misery, he continues developing nuclear weapons and long-range missiles unabated. North Korea already has the technology to annihilate Seoul and Tokyo, and experts predict it will soon be able to mount nukes on missiles that can reach Los Angeles in thirty minutes. So long as its nuclear stockpile exists, preemptive military action against the country is all but impossible, and Kim Jong Un's rule will likely continue.

But that doesn't mean he'll ever feel that his power is wholly secure. In May, North Korea issued a long letter that accused the CIA of plotting to assassinate its leader, claiming as proof that American operatives were paying tens of thousands of dollars in cash to carry out the deed. (The North Koreans have not released any evidence.) In June, South Korean intelligence told lawmakers that Kim Jong Un was becoming increasingly paranoid, and had taken to traveling at night, in decoy cars.

Since then, new details have emerged about Kim Jong Nam's fateful trip. A Japanese newspaper published security footage placing Kim in a Malaysian hotel with an American who's suspected of being a U. S. spy. In the images, Kim is wearing the same pale gray blazer and carrying the same black backpack that he was seen with on the day of his death. The bag was stuffed with $120,000 in cash, all in $100 bills, the paper reported, citing unnamed Malaysian sources.

As Kim Jong Un's paranoia deepens, which family members are in his crosshairs? His aunt has not been seen in public since her husband Jang's 2013 execution. The supreme leader's sister has been promoted to a high-ranking propaganda post in the party, but she does not appear poised to overthrow her brother. Others in the Kim royal family are lying low: There is little mention in state media of their publicity-shy brother, or an older half sister. It is unclear where a nephew, Kim Jong Nam's second son, may be.

And then there's Kim Han Sol, now twenty-two, whose video was released just weeks after his father's death. Though his mother was Kim Jong Nam's mistress, and he never met his grandfather or uncle, he's a direct descendant of Kim Il Sung, and therefore an inheritor of the Mount Paektu bloodline.

With his hipster haircut, geek-chic glasses, and charisma, Han Sol is unlike any Kim family member we've seen: intelligent, curious, and open-minded. Educated almost exclusively abroad—including at Sciences Po in France, alma mater of five of the last seven French presidents—he speaks fluent English. In the few interviews he's given, Han Sol has championed democracy, peace, and diplomacy. In one, with a Finnish television station in 2012, he praised the Arab Spring, calling the uprising that unseated Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi a "revolution." In perhaps the most surprising moment of the conversation, he referred to his uncle as a "dictator." Kim said his dream was to one day "go back and make things better, and make it easier for the people there. I also dream of unification."

Kim Han Sol has the birthright to lead and a wish for his country to open up in ways that appeal to the U. S. and its allies. "This is a cosmopolitan, bright young kid," says Straub, from the Sejong Institute. "Maybe he is the real threat, in the long term, to the regime."

The site for Cheollima Civil Defense, the group that Kim Han Sol credits with saving him, his mother, and his sister, published a declaration explaining that the three were evacuated with the help of China, the United States, the Netherlands, and a fourth, unnamed country. "This will be the first and last statement on this particular matter," it reads, "and the present whereabouts of this family will not be addressed."

Little is known about the group. Could it be run by North Korean defectors? South Korean intelligence? The country's constitution grants nationality to all Koreans born on the peninsula, north or south, and the government has a system for reintegrating—and protecting—high-profile defectors. European allies? Lody Embrechts, the Dutch ambassador to South Korea, was thanked on Cheollima's site; he has remained tight-lipped about his involvement. Or is it an ad hoc group the world will never hear from again? At press time, its website was no longer live.

Where Kim Han Sol is in hiding is a guessing game among those who monitor North Korea. Of the dozens of reporters, experts, diplomats, and agents I spoke with, no one knew—or was willing to share—any information. Is he in the United States, or a U. S.-allied country, under CIA protection? Or is he in Europe, where he has exiled family and a tight circle of friends?

The one place everyone was sure he isn't is North Korea.

No comments:

Post a Comment