가산 카나파니

가산 카나파니 غسان كنفاني | |

|---|---|

| |

| 출생 | 1936년 4월 8일 팔레스타인 위임통치령 아크레 |

| 사망 | 1972년 7월 8일(36세) 레바논 베이루트 |

| 사인 | 암살 |

| 성별 | 남성 |

| 직업 | 작가, 정치인 |

가산 파이즈 카나파니(아랍어: غسان فايز كنفاني, 영어: Ghassan Fayiz Kanafani, 1936년 4월 8일 ~ 1972년 7월 8일)는 팔레스타인인 작가, 언론인, 정치인이다. 아랍권에서 팔레스타인을 대표하는 작가로 꼽힌다.[1] 저서로 《뜨거운 태양 아래서》, 《너에게 남은 모든 것》, 《하이파에 돌아와서》 등이 있다.

1936년 팔레스타인 위임통치령 아크레에서 태어났다. 1948년 팔레스타인 전쟁 때 시온주의 민병대에 의해 퇴거당해 다마스쿠스로 이주하였고, 다마스쿠스의 난민촌에서 학생을 가르치며 아동을 위한 문학을 쓰기 시작했다. 1952년부터 다마스쿠스 대학교에서 아랍 문학을 전공하였으나 주르지 하바시가 주도한 아랍 민족주의 운동에 가담한 것을 이유로 학위를 마치기 전에 추방당했다. 쿠웨이트, 베이루트 등으로 거처를 옮겼으며 그 와중에 마르크스주의로 기울었다.

1961년 덴마크의 교육자, 아동 권리 운동가인 애니 회버(Anni Høver)와 결혼했다. 1963년 소설 《뜨거운 태양 아래서》(Men in the Sun)로 주목을 받았으며, 그해 팔레스타인 해방대중전선에 가입하여 대변인이 되었다.

1972년 베이루트에서 모사드가 차량에 설치한 폭탄이 터져 사망하였다. 이 암살은 팔레스타인 해방대중전선이 가담한 로드 공항 사건에 대한 이스라엘의 보복으로서 수행되었으나, 카나파니에 대한 암살 계획이 그 이전부터 존재했던 것으로 보인다.[2]

Ghassan Kanafani

Ghassan Kanafani | |

|---|---|

غسان كنفاني | |

Graffiti tribute to Kanafani in the Palestinian territories, 2004 | |

| Born | 8 April 1936 |

| Died | 8 July 1972 (aged 36) Beirut, Lebanon |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Nationality | Palestinian |

| Other names | Faris Faris |

| Education | Damascus University (expelled) |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1953–1972 |

| Organization | PFLP |

| Spouse | Anni Høver (m. 1961) |

| Children | 2 |

Ghassan Fayiz Kanafani (Arabic: غسان فايز كنفاني; 8 April 1936 – 8 July 1972) was a prominent Palestinian author and militant, considered to be a leading novelist of his generation and one of the Arab world's leading Palestinian writers.[1] Kanafani's works have been translated into more than 17 languages.[1]

Kanafani was born in Acre, Mandatory Palestine in 1936. During the 1948 Palestine war, his family was forced out of their hometown by Zionist militias. Kanafani later recalled the intense shame he felt when, at the age of 12, he watched the men of his family surrender their weapons to become refugees.[2] The family settled in Damascus, Syria, where he completed his primary education. He then became a teacher for displaced Palestinian children in a refugee camp, where he began writing short stories in order to help his students contextualize their situation.[3] He began studying for an Arabic Literature degree at the University of Damascus in 1952, but before he could complete his degree, he was expelled from the university for his political affiliations with the Movement of Arab Nationalists (MAN), to which he had been recruited by George Habash. He later relocated to Kuwait and then Beirut, where he became immersed in Marxism.

In 1961, he married Anni Høver, a Danish pedagogue and children's rights activist, with whom he had two children.[4] He became an editor and wrote articles for a number of Arab magazines and newspapers. His 1963 novel Men in the Sun received widespread acclaim and, along with A World that is Not Ours, symbolizes his first period of pessimism, which was later reversed in favor of active struggle in the aftermath of the 1967 Six-Day War. That year, he joined the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and became its spokesman. In 1969, he drafted a PFLP program in which the movement officially adopted Marxism–Leninism, which marked a departure from pan-Arab nationalism towards revolutionary Palestinian struggle.[5]

In 1972, while he was in Beirut, Kanafani and his 17-year-old niece Lamees were killed by a bomb planted in his car by Mossad, which was suspected to be in response for the PFLP's role in the Lod Airport massacre; however, Kanafani's assassination may have been planned long before.[6] Kanafani appeared with the massacre's perpetrators in a photograph shortly before the massacre and defended the tactics used in the massacre shortly before his assassination.

Early life

Kanafani was born in Acre in 1936 to a middle-class Sunni Muslim family.[7][better source needed] He was the third child of Muhammad Fayiz Abd al Razzag, a lawyer who was active in the Palestinian nationalist movement that opposed the British Mandate and its policies of enabling Jewish immigration, and who had been imprisoned on several occasions by the British when Ghassan was still a child.[8] Ghassan received his early education in a French Catholic missionary school in the city of Jaffa.[8]

In May, when the outbreak of hostilities in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War spilled over into Acre, Kanafani and his family were forced into exile,[9] joining the Palestinian exodus. In a letter to his own son written decades later, he recalled the intense shame he felt on observing, aged 10, the men of his family surrendering their weapons to become refugees.[2] After fleeing some 17 kilometres (11 mi) north to neighbouring Lebanon, they finally settled in Damascus, Syria.[8] They were relatively poor; the father set up a small lawyer's practice, with the family income being supplemented by the boys' part-time work. There, Kanafani completed his secondary education, receiving a United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) teaching certificate in 1952. He was first employed as an art teacher for some 1,200 displaced Palestinian children in a refugee camp, where he began writing short stories in order to help his students contextualize their situation.[3]

Political background

| Part of a series on |

| Palestinian nationalism |

|---|

In 1952, Kanafani also enrolled in the Department of Arabic Literature at the University of Damascus. The next year, he met George Habash, who introduced him to politics and was to exercise an important influence on his early work. In 1955, before he could complete his degree, with a thesis on "Race and Religion in Zionist Literature", which was to form the basis for his 1967 study On Zionist Literature, Kanafani was expelled from the university for his political affiliations with the Movement of Arab Nationalists (MAN) to which Habash had recruited him.[5] Kanafani moved to Kuwait in 1956, following his sister Fayzah Kanafani[10] and the brother who had preceded him there,[3] to take up a teaching position. He spent much of his free time absorbed in Russian literature. In the following year, he became editor of Jordanian Al Ra'i (The Opinion), which was an MAN-affiliated newspaper.[5]

In 1960, he relocated again, this time to Beirut, on the advice of Habash, where he began editing the MAN mouthpiece al-Hurriya and took up an interest in Marxist philosophy and politics.[5] In 1961, he married Danish pedagogue and children's rights activist Anni Høver, with whom he had two children.[4] In 1962, Kanafani was forced briefly to go underground since he, as a stateless person, lacked proper identification papers. He reappeared in Beirut later the same year, and took up editorship of the Nasserist newspaper Al Muharrir (The Liberator), editing its weekly supplement "Filastin" (Palestine).[5] He went on to become an editor of another Nasserist newspaper, Al Anwar (The Illumination), in 1967, writing essays under the pseudonym of Faris Faris.[11] He was also editor of Assayad magazine, which was the sister publication of Al Anwar.[5] In the same year, Kanafani also joined The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and in 1969, resigned from Al Anwar to edit the PFLP's weekly magazine, Al Hadaf ("The Goal"), while drafting a PFLP program in which the movement officially took up Marxism-Leninism. This marked a departure from pan-Arab nationalism towards revolutionary Palestinian struggle.[5] Kanafani was also one of the contributors to Lotus, a magazine launched in 1968 and financed by Egypt and the Soviet Union.[12] At the time of his assassination, he held extensive contacts with foreign journalists and many Scandinavian anti-Zionist Jews.[13] His political writings and journalism are thought to have made a major impact on Arab thought and strategy at that time.[14]

Literary output

Though prominent as a political thinker, militant, and journalist, Kanafani is on record as stating that literature was the shaping spirit behind his politics.[15] Kanafani's literary style has been described as "lucid and straightforward";[11] his modernist narrative technique—using flashback effects and a wide range of narrative voices—represents a distinct advance in Arabic fiction.[16] Ihab Shalback and Faisal Darraj sees a trajectory in Kanafani's writings from the simplistic dualism depicting an evil Zionist aggressor to a good Palestinian victim, to a moral affirmation of the justness of the Palestinian cause where however good and evil are not absolutes, until, dissatisfied by both, he began to appreciate that self-knowledge required understanding of the Other, and that only by unifying both distinct narratives could one grasp the deeper dynamics of the conflict.[17][18]

In many of his fictions, he portrays the complex dilemmas Palestinians of various backgrounds must face. Kanafani was the first to deploy the notion of "resistance literature" ("adab al-muqawama") with regard to Palestinian writing;[5][14] in two works, published respectively in 1966 and 1968,[5] one critic, Orit Bashkin, has noted that his novels repeat a certain fetishistic worship of arms, and that he appears to depict military means as the only way to resolve the Palestinian tragedy.[9][5] Ghassan Kanafani began writing short stories when he was working in the refugee camps. Often told as seen through the eyes of children, the stories manifested out of his political views and belief that his students' education had to relate to their immediate surroundings. While in Kuwait, he spent much time reading Russian literature and socialist theory, refining many of the short stories he wrote, winning a Kuwaiti prize.[11]

Men in the Sun (1962)

In 1962, his novel, Men in the Sun (Rijal fi-a-shams), reputed to be "one of the most admired and quoted works in modern Arabic fiction,"[19] was published to great critical acclaim.[9] Rashid Khalidi considers it "prescient".[20]

The story is an allegory of Palestinian calamity in the wake of the nakba in its description of the defeatist despair, passivity, and political corruption infesting the lives of Palestinians in refugee camps.[16]

The central character is an embittered ex-soldier, Abul Khaizuran, disfigured and rendered impotent by his wounds, whose cynical pursuit of money often damages his fellow countrymen.[11][21]

Three Palestinians, the elderly Abu Qais, Assad, and the youth Marwan, hide in the empty water tank of a lorry in order to cross the border into Kuwait. They have managed to get through as Basra and drew up to the last checkpoint. Abul Khaizuran, the truck driver, tries to be brisk but is dragged into defending his honor as the Iraqi checkpoint officer teases him by suggesting he had been dallying with prostitutes.

The intensity of heat within the water carrier is such that no one could survive more than several minutes, and indeed they expire inside as Khaizuran is drawn into trading anecdotes that play up a non-existent virility—they address him as though he were effeminized, with the garrulous Abu Baqir outside in an office. Their deaths are to be blamed, not on the effect of the stifling effect of the sun's heat, but on their maintaining silence as they suffer.[19][22]

The ending has often been read as a trope for the futility of Palestinian attempts to try to build a new identity far away from their native Palestine, and the figure of Abul Khaizuran a symbol of the impotence of the Palestinian leadership. Amy Zalman has detected a covert leitmotif embedded in the tale, in which Palestine is figured as the beloved female body, while the male figures are castrated from being productive in their attempts to seek another country.

In this reading, a real national identity for Palestinians can only be reconstituted by marrying awareness of gender to aspirations to return.[23]

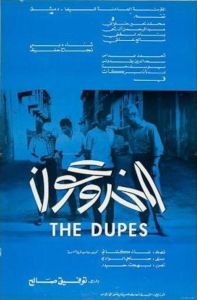

A film based on the story, Al-Makhdu'un (The Betrayed or The Dupes), was produced by Tewfik Saleh in 1972.[24]

The Dupes 1973

| The Dupes المخدوعون | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Tewfik Saleh |

| Written by | Ghassan Kanafani Tewfik Saleh |

| Starring | Mohamed Kheir-Halouani |

| Cinematography | Bahgat Heidar |

Release date |

|

Running time | 107 minutes |

| Country | Syria |

| Language | Arabic |

The Dupes (Arabic: المخدوعون, 'al-makhdūʿūn') is a 1973 Syrian drama film directed and co-written by Tewfik Saleh and starring Mohamed Kheir-Halouani, Abderrahman Alrahy, Bassan Lotfi, Saleh Kholoki and Thanaa Debsi. Based on Ghassan Kanafani's 1963 novel, Men in the Sun, the film portrays the lives of three Palestinian refugees after the 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight by following three generations of men who made their way from Palestine to Iraq in the hope of reaching Kuwait to pursue their dreams of freedom and prosperity. The Dupes received very positive reviews from critics and won multiple awards locally and internationally. It was entered into the 8th Moscow International Film Festival,[1] where it was nominated for the Golden Prize, and the 1972 Carthage Film Festival, where it won the Tanit d'Or.[2]

Cast

- Mohamed Kheir-Halouani as Abou Keïss

- Abderrahman Alrahy as Abou Kheizarane

- Bassan Lofti Abou-Ghazala as Assaad

- Saleh Kholoki as Marouane

- Thanaa Debsi as Om Keïss

See also

References

- "8th Moscow International Film Festival (1973)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Gugler, Josef; Yaqub, Nadia (2011). Film in the Middle East and North Africa: Creative Dissidence. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292723276.

External links

All That's Left to You (1966)

All That's Left to You (Ma Tabaqqah Lakum) (1966) is set in a refugee camp in the Gaza Strip.[19] It deals with a woman, Maryam, and her brother, Hamid, both orphaned in the 1948 war, their father dying in combat—his last words being a demand that they abstain from marriage until the national cause has been won—and their mother separated from them in the flight from Jaffa. She turns up in Jordan, they end up with an aunt in Gaza, and live united in a set of Oedipal displacements; Hamid seeks a mother-substitute in his sister, while Maryam entertains a quasi incestuous love for her brother. Maryam eventually breaks the paternal prohibition to marry a two-time traitor, Zakaria, since he is bigamous, and because he gave the Israelis information to capture an underground fighter, resulting in the latter's death. Hamid, outraged, tramps off through the Negev, aspiring to reach their mother in Jordan. The two episodes of Hamid in the desert, and Maryam in the throes of her relationship with Zakaria, are interwoven into a simultaneous cross-narrative: the young man encounters a wandering Israeli soldier who has lost contact with his unit, and wrestles his armaments from him, and ends up undergoing a kind of rebirth as he struggles with the desert. Maryam, challenged by her husband to abort their child, whom she will call Hamid, decides to save the child by killing Zakaria.[25][26] This story won the Lebanese Literary prize in that year.[5][27]

Umm Sa'ad (1969)

In Umm Sa'ad (1969), the impact of his new revolutionary outlook is explicit as he creates the portrait of a mother who encourages her son to take up arms as a fedayeen in full awareness that the choice of life might eventuate in his death.[11]

Return to Haifa (1970)

Return to Haifa (A'id lla Hayfa) (1970) is the story of a Palestinian couple, Sa'id and his wife Safiyya, who have been living for nearly two decades in the Palestinian town of Ramallah, which was under Jordanian administration until it and the rest of the West Bank were conquered in the Six-Day War. The couple must learn to face the fact that their five-month-old child, a son they were forced to leave behind in their home in Haifa in 1948, has been raised as an Israeli Jew, an echo of the Solomonic judgement.[28][29] The father searches for the real Palestine through the rubble of memory, only to find more rubble. The Israeli occupation means that they have finally an opportunity to go back and visit Haifa in Israel. The journey to his home in the district of Halisa on the al-jalil mountain evokes the past as he once knew it.[30] The dissonance between the remembered Palestinian past and the remade Israeli present of Haifa and its environs creates a continuous diasporic anachronism.[31] The novel deals with two decisive days, one 21 April 1948, the other 30 June 1967; the earlier date relates to the fall of Haifa, when the Haganah launched its assault on the city and Palestinians who were not killed in the battle fled. Sa'id and his wife were ferried out on British boats to Acre. A Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor, Evrat Kushan, and his wife, Miriam, find their son Khaldun in their home, and take over the property and raise the toddler as a Jew, with the new name "Dov". When they visit the home, Kushen's wife greets them with the words: "I've been expecting you for the a long time." Kushen's recall of the events of April 1948 confirms Sa'id's own impression, that the fall of the town was coordinated by the British forces and the Haganah. When Dov returns, he is wearing an IDF uniform, and vindictively resentful of the fact they abandoned him. Compelled by the scene to leave the home, the father reflects that only military action can settle the dispute, realizing however that, in such an eventuality, it may well be that Dov/Khaldun will confront his brother Khalid in battle. The novel conveys nonetheless a criticism of Palestinians for the act of abandonment, and betrays a certain admiration for the less than easy, stubborn insistence of Zionists, whose sincerity and determination must be the model for Palestinians in their future struggle. Ariel Bloch indeed argues that Dov functions, when he rails against his father's weakness, as a mouthpiece for Kanafani himself. Sa'id symbolizes irresolute Palestinians who have buried the memory of their flight and betrayal of their homeland.[32] At the same time, the homeland can no longer be based on a nostalgic filiation with the past as a foundation, but rather an affiliation that defies religious and ethnic distinctions.[33][34][35] Notwithstanding the indictment of Palestinians, and a tacit empathy with the Israeli enemy's dogged nation-building, the novel's surface rhetoric remains keyed to national liberation through armed struggle.[36] An imagined aftermath to the story has been written by Israeli novelist Sami Michael, a native Arabic-speaking Israeli Jew, in his Yonim be-Trafalgar (Pigeons in Trafalgar Square).[37]

His article on Izz ad-Din al-Qassam, published in the PLO's Research Centre Magazine, Shu'un Filistiniyya (Palestinian Affairs), was influential in diffusing the image of the former as a forerunner of the Palestinian armed struggle, and, according to Rashid Khalidi, consolidated the Palestinian narrative that tends to depict failure as a triumph.[38]

Assassination

On 8 July 1972, Kanafani, was assassinated in Beirut by the Mossad, the Israeli foreign intelligence service. When Kanafani turned on the ignition of his Austin 1100, a grenade connected to the ignition switch detonated and in turn detonated a 3 kilo plastic bomb planted behind the bumper bar.[39] Both Kanafani and his 17-year-old niece Lamees Najim, who had been accompanying him, were killed.[40][15]

It was suspected that his killing was in retaliation for the Lod Airport massacre, carried out days earlier by three members of the Japanese Red Army. However, some reports suggest that the assassination may have been planned before these events.[6] As the PFLP's spokesperson, Kanafani had claimed responsibility for the attack on behalf of the organization. He was also identified in photographs taken with the three Japanese militants shortly before the operation, which reportedly contributed to his inclusion on a Mossad hit list.[41]

During the 1970 hijackings, Kanafani and his deputy, Bassam Abu Sharif, publicly demanded that Israel release Palestinian prisoners. According to journalist Kameel Nasr, both had begun to express opposition to indiscriminate violence by the time of Kanafani's death.[42] His assassination occurred amid a broader regional escalation: Israel had arrested hundreds of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza—actions Haaretz described as taking "counter-hostages"—and launched a large-scale military operation in southern Lebanon. Around the same time, the Jewish Defense League in London abducted three Egyptian embassy employees.[43]

Rumors circulated that Beirut's security forces may have been complicit in Kanafani's assassination.[44] Two weeks later, Abu Sharif survived an attempt on his life. He later alleged that Israel had worked with Arab intermediaries to carry out both attacks. One suspected collaborator, Abu Ahmed Yunis, a senior PFLP member, was executed by the group in 1981 for embezzlement and ordering the killing of another official.[45]

Kanafani's obituary in Lebanon's The Daily Star wrote that: "He was a commando who never fired a gun, whose weapon was a ball-point pen, and his arena the newspaper pages."[14][46]

On his death, several uncompleted novels were found among his Nachlass, one dating back as early as 1966.[47]

Commemoration

A collection of Palestinian poems, The Palestinian Wedding: A Bilingual Anthology of Contemporary Palestinian Resistance Poetry, which took its title from the eponymous poem by Mahmoud Darwish, was published in his honor. He was the posthumous recipient of the Afro-Asia Writers' Conference 's Lotus Prize for Literature in 1975.[48][49] Ghassan Kanafani's memory was upheld through the creation of the Ghassan Kanafani Cultural Foundation, which has since established eight kindergartens for the children of Palestinian refugees.[50] His legacy lives on among the Palestinians, and he is considered to be a leading novelist of his generation and one of the Arab world's leading Palestinian writers.[1]

Works

- Mawt Sarir Raqam 12 (1961) (موت سرير رقم 12, The Death of Bed Number 12) (short story)

- Ard al-Burtuqal al-Hazin (1963) (أرض البرتقال الحزين, The Sad Orange Land). ISBN 978-9963610808

- Rijal fi ash-Shams (1963) (رجال في الشمس, Men in the Sun). ISBN 978-0894108570

- Al-bab (1964) (الباب, The Door). ISBN 978-9963610839

- 'Aalam Laysa Lana (1965) (عالمٌ ليس لنا, A World Not Our Own). ISBN 978-9963610952

- 'Adab al-Muqawamah fi Filastin al-Muhtalla 1948–1966, (1966) (أدب المقاومة في فلسطين المحتلة 1948–1966, Literature of Resistance in Occupied Palestine). ISBN 978-9963610907

- Ma Tabaqqa Lakum (1966) (ما تبقّى لكم, All That's Left to You). ISBN 978-1566565486

- Fi al-Adab al-Sahyuni (1967) (في الأدب الصهيوني, On Zionist Literature). ISBN 978-1739985233

- An ar-Rijal wa-l-Banadiq (1968) (عن الرجال والبنادق, On Men and Rifles). ISBN 978-9963610877

- Umm Sa'd (1969) (أم سعد, Umm Sa'd). ISBN 9788440427588

- A'id ila Hayfa (1970) (عائد إلى حيفا, Return to Haifa). ISBN 978-0894108907

- A 'ma wal-Atrash, (1972) (الأعمى والأطرش, The Blind Man and The Deaf Man)

- Barquq Naysan (1972) (برقوق نيسان, The Apricots of April)

- Al-Qubba'ah wa-l-Nabi (1973) (القبعة والنبي, The Hat and the Prophet) – incomplete

- Thawra 1936-39 fi Filastin (1974) (ثورة 1936-39 في فلسطين, The 1936-39 Revolt in Palestine) (45–page pamphlet)

- Jisr ila-al-Abad (1978) (جسر إلى الأبد, A Bridge to Eternity). ISBN 978-9963610815

- Al-Gamis al-Masruq wa-Qisas Ukhra, (1982) (القميص المسروق وقصص أخرى, The Stolen Shirt and Other Stories) ISBN 978-9963610921

- Arabic Short Stories (1983) (transl. by Denys Johnson-Davies). ISBN 9780520089440

- Faris Faris (1996) (فارس فارس, Knight Knight)

Novels

- Men in the Sun | رجال في الشمس (ISBN 9789963610853, Rimal Publications, 2013)

- All That's Left to You | ماتبقى لكم (ISBN 9789963610945, Rimal Publications, 2013)

- Umm Saad | أم سعد (ISBN 9789963610938, Rimal Publications, 2013)

- The Lover | العاشق (ISBN 9789963610860, Rimal Publications, 2013)

- Returning to Haifa | عائد الى حيفا (ISBN 9789963610914, Rimal Publications, 2013)

- The Other Thing (Who Killed Laila Hayek?) | الشيء الآخر (ISBN 9789963610884, Rimal Publications, 2013)

Short stories

- "Death of Bed No. 12"] | موت سرير رقم ١٢ (ISBN 9789963610822, Rimal Publications, 2013)

- "Land of Sad Oranges" | ارض البرتقال الحزين (ISBN 9789963610808, Rimal Publications, 2013)

- "A World Not Our Own" | عالم ليس لنا (ISBN 9789963610952, Rimal Publications, 2013)

- "Of Men and Rifles" | الرجال والبنادق (ISBN 9789963610877, Rimal Publications, 2013)

- "The Stolen Shirt" | القميص المسروق (ISBN 9789963610921, Rimal Publications, 2013)

Plays

- A Bridge to Eternity | جسر إلى الأبد (ISBN 9789963610815, Rimal Publications, 2013)

- The Door | الباب (ISBN 9789963610839, Rimal Publications, 2013)

- The Hat and the Prophet | القبعه والنبي (ISBN 9789963610846, Rimal Publications, 2013)

Studies

- Resistance Literature in Occupied Palestine 1948–1966 | أدب المقاومة في فلسطين المحتلة ١٩٤٨-١٩٦٦ (ISBN 9789963610907, Rimal Publications, 2013)

- Palestinian Literature of Resistance Under Occupation 1948–1968 | الأدب الفلسطيني المقاوم تحت الإحتلال ١٩٤٨ – ١٩٦٨ (ISBN 9789963610891, Rimal Publications, 2013)

- In Zionist Literature | في الأدب الصهيوني (ISBN 9789963610983, Rimal Publications, 2013)

Translations into English

- Kanafani, Ghassan (2023). The Revolution of 1936–1939 in Palestine: Background, Details, and Analysis. Hazem Jamjoum (translator) (1st ed.). 1804 Books. ISBN 978-1736850046.

- Kanafani, Ghassan (2022). On Zionist Literature. Mahmoud Najib (translator) (1st ed.). Ebb Books. ISBN 978-1739985233.

- Kanafani, Ghassan (1998). Men in the Sun and Other Palestinian Stories. Hilary Kilpatrick (translator) (2nd ed.). Three Continents Press. ISBN 9780894108570.

- Kanafani, Ghassan (2000). Palestine's Children: Returning to Haifa & Other Stories. Barbara Harlow (contributor), Karen E. Riley (contributor). Three Continents Press. ISBN 9780894108907.

- Kanafani, Ghassan (2004). All That's Left to You. Roger Allen (contributor), May Jayyusi (translator) and Jeremy Reed (translator). Interlink World Fiction. ISBN 9781566565486.

- Halliday, Fred (May–June 1971). "Ghassan Kannafani: On the PFLP and the September crisis (interview)". New Left Review. I (67).

References

- "In memoriam: Ghassan Kanafani, Palestine's most famous novelist and political activist killed by Israel". New Arab. 9 July 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- Schmitt 2014.

- Zalman 2004, p. 685.

- Haugbolle, Sune; Olsen, Pelle Valentin (2023). "Emergence of Palestine as a Global Cause". Middle East Critique. 32 (1): 139. doi:10.1080/19436149.2023.2168379. hdl:10852/109792. S2CID 256654768.

- Rabbani 2005, p. 275.

- Nasr, Kameel B. (23 April 2007). Arab and Israeli Terrorism: The Causes and Effects of Political Violence, 1936-1993. McFarland. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7864-3105-2. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

It was suspected that Kanafani was killed in retaliation for the Japanese Red Army airport massacre just past, but the assassination may have been planned long before.

- Abdel-Malek, Kamal (2016), The Rhetoric of Violence: Arab-Jewish Encounters in Contemporary Palestinian Literature and Film, Springer, p. 35.

- Zalman 2004, p. 683.

- Bashkin 2010, p. 96.

- Ghabra 1987, pp. 100–101: She had moved to Kuwait in 1950 to work as a teacher and married Husayn Najim.

- Zalman 2004, p. 688.

- Manji, Firoze (3 March 2014). "The Rise and Significance of Lotus". CODESRIA. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- Nasr 1997, p. 65.

- Harlow 1996, p. 179.

- Zalman 2006, p. 48.

- Saloul 2012, p. 107.

- Shalback 2010, p. 78.

- Mendelson-Maoz 2014, p. 46.

- Irwin 1997, p. 23.

- Khalidi 2009, p. 212.

- Zalman 2006, pp. 53–60.

- Abraham 2014, pp. 101–102.

- Zalman 2006, pp. 48, 52–53.

- Zalman 2006, p. 52.

- Zalman 2006, p. 65.

- Zalman 2004, p. 689.

- Zalman 2006, pp. 65–71.

- Mendelson-Maoz 2014, p. 47.

- Bloch 2000, p. 358.

- Zalman 2004, p. 689

- Bardenstein 2007, p. 26.

- Bloch 2000, p. 361.

- Attar 2010, pp. 159–162.

- Mendelson-Maoz 2014, pp. 46–53.

- Shalback 2010, pp. 78.

- Bloch 2000, p. 362.

- Mendelson-Maoz 2014, pp. 47–48.

- Khalidi 2009, p. 195.

- Pedahzur 2009, pp. 39–40.

- Harlow 1994, p. 181.

- Pedazhur, Ami: The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism, p. 39.

- Nasr 2007, p. 65

- Nasr 2007, p. 54

- Khalili 2007, p. 133.

- Nasr 1997, p. 65

- Abraham 2014, p. 101.

- Rabbani 2005, p. 276.

- Rabbani 2005, pp. 275–276.

- Reigeluth 2008, p. 308.

- Abu Saba 1999, p. 250.

Bibliography

- Abraham, Matthew (2014). Intellectual Resistance and the Struggle for Palestine. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-03195-2. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Abu Saba, Mary Bentley (1999). "Profiles of Foreign Women in Lebanon during the Civil War". In Shehadeh, Lamia Rustum (ed.). Women and War in Lebanon. University of Florida Press. pp. 229–258. ISBN 978-0-813-01707-5. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Attar, Samar (2010). Debunking the Myths of Colonization: The Arabs and Europe. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-761-85039-7. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Bardenstein, Carol (2007). "Figures of Dasporic Cultural Production: Some entries from the Palestinian Lexicon". In Baronian, Marie-Aude; Besser, Stephan; Jansen, Yolande (eds.). Diaspora and Memory: Figures of Displacement in Contemporary Literature, Arts and Politics. Rodopi. pp. 19–31. ISBN 978-9-042-02129-7. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Bloch, Ariel A. (2000). "Ideology and Realism in a Palestinian Novella:Ghassam Kanafani's Return to Haifa". In Brinner, William M.; Hary, Benjamin H.; Hayes, John Lewis; Astren, Fred (eds.). Judaism and Islam: Boundaries, Communications, and Interaction:Essays in Honor of William M.Brinner. BRILL. pp. 355–364. ISBN 978-9-004-11914-7. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Bashkin, Orit (2010). "'Nationalism as a Cause: Arab Nationalism in the writings of Ghassan Kanafani". In Schumann, Christoph (ed.). 'Nationalism and Liberal Thought in the Arab East: Ideology and Practice. Routledge. pp. 92–111. ISBN 978-1-135-16361-7. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Ensalaco, Mark (2012). Middle Eastern Terrorism: From Black September to 11 September. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-812-20187-1. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Farsoun, Samih K. (2004). Culture and Customs of the Palestinians. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-192-83318-1.

- Ghabra, Shafeeq N. (1987). Palestinians in Kuwait: The Family and the Politics of Survival. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-813-37446-8.

- Harlow, Barbara (1994). "Writers and Assassinations". In Lemelle, Sidney J.; Kelley, Robin D G (eds.). Imagining Home: Class, Culture, and Nationalism in the African Diaspora. Verso. pp. 167–184. ISBN 978-0-860-91585-0. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Harlow, Barbara (1996). After Lives: Legacies of Revolutionary Writing. Verso. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-859-84180-8. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Irwin, Robert (1997). "Arab Countries". In Sturrock, John (ed.). The Oxford Guide to Contemporary World Literature. Oxford University Press. pp. 22–38. ISBN 978-0-192-83318-1.

- Kanafani, Ghassan (1999). Kilpatrick, Hilary (ed.). Men in the Sun and Other Palestinian Stories. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-894-10857-0.

- Khalidi, Rashid (2009). Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9781557536808. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Khalili, Laleh (2007). Heroes and Martyrs of Palestine: The Politics of National Commemoration. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-46282-2. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Mendelson-Maoz, Adia (2014). Multiculturalism in Israel: Literary Perspectives. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-557-53680-8. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Nasr, Kameel B. (1997). Arab and Israeli Terrorism: The Causes and Effects of Political Violence, 1936–1993. McFarland. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-786-40280-9.

- Pedahzur, Ami (2009). The Israeli Secret Services and the Struggle Against Terrorism. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14042-3.

- Rabbani, Mouin (2005). "Ghassan Kanafani". In Mattar, Philip (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Palestinians. Infobase Publishing. pp. 275–276. ISBN 978-0-816-06986-6. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Reigeluth, Stuart (2008). "The Poetic Prose of Mahmoud Darwish and Mourid Barghouti". In Nassar, Hala Khamis; Rahman, Najat (eds.). Mahmoud Darwish, Exile's Poet: Critical Essays. Olive Branch Press. pp. 293–318. ISBN 978-1-566-56664-3.

- Saloul, Ihab (2012). Catastrophe and Exile in the Modern Palestinian Imagination: Telling Memories. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-00138-2. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Shalback, Ihab (2010). "Edward Said and the Palestinian Experience". In Pugliese, Joseph (ed.). Transmediterranean: Diasporas, Histories, Geopolitical Spaces. Peter Lang. pp. 71–83. ISBN 978-9-052-01619-1. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- Schmitt, Paula (14 May 2014). "'Interview with Leila Khaled: 'BDS is effective, but it doesn't liberate land','". +972 magazine 17. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Zalman, Amy (2004). "'Nationalism as a Cause: Arab Nationalism in the writings of Ghassan Kanafani". In Schumann, Christoph (ed.). Great World Writers: Twentieth Century. Vol. 5. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 682–692. ISBN 978-0-761-47473-9.

- Zalman, Amy (2006). "Gender and the Palestinian Narrative of Return in Two Novels by Ghassan Kanafani". In Suleiman, Yasir; Muhawi, Ibrahim (eds.). Literature and Nation in the Middle East. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 48–77. ISBN 978-0-748-62073-9.

External links

- Ghassan Kanafani at the Marxists Internet Archive.

- Ghassan Kanafani: The Founder of the Modern Palestinian Novel, Yemen Times, 06.10.2008.

- Ghassan Kanafani and the era of revolutionary Palestinian media. Al Jazeera.

- ===

ガッサーン・カナファーニー

ガッサーン・カナファーニー(アラビア語: غسان كنفاني, 転写:Ghassān Kanafānī、標準英字表記:Ghassan Kanafani、1936年4月9日 - 1972年7月8日)は、現代パレスチナを代表する小説家[1]であり、ジャーナリスト。『太陽の男たち』、『ハイファに戻って』などの作品がとくに知られている。パレスチナ解放人民戦線(PFLP)の活動家でもあり、1972年に爆殺された。

略歴

ガッサーン・ファイーズ・カナファーニーは1936年、イギリス委任統治下パレスチナのアッカ(現イスラエル領)で、スンナ派ムスリムの両親のもとに生まれた。弁護士だった父は、中流家庭の習いとして彼をフランス系のミッション・スクールに入学させた[2]。しかし1948年、武装ユダヤ人によるデイル・ヤーシーン村虐殺事件が起こるとその後の混乱はアッカにも及び、一家はシリアのザバダーニへと逃れた[2]。間もなく一家でダマスカスに移り、そこでパレスチナ難民として生活する。家計は厳しくなり、ガッサーンも夜学に通いながら日中は稼ぎに出る生活を送った[2]。

1952年、ダマスカスで中等教育を終えるとともに、国連パレスチナ難民救済事業機関(UNRWA)から教職の資格を得、同年ダマスカス大学のアラビア語学科に入学する。しかし翌1953年にジョージ・ハバシュの紹介で左派系汎アラブ主義団体であるHarakat al-Qawmiyyin al-Arab(アラブ人の民族運動-en:Arab Nationalist Movement (ANM)) )に参加し、その事が原因で1955年に退学となった。

1955年、ダマスカスでUNRWAが運営する学校で教員となる[2]。翌年には姉が住むクウェートに移り、ここでも教職に就く[3]。その経験は、短編小説「路傍の菓子パン」(『ハイファに戻って/太陽の男たち』所収。)に活かされている[4]。その一方で政治活動にも力を注ぎ、ANMの機関紙「al-Ra'i」の編集を担当する。この時期より糖尿病の症状が現れ、生涯インシュリン注射が欠かせなくなったとされる[3]。

1960年ANMの機関紙アル・フッリーヤからの求めによってレバノンのベイルートへ移り、同紙の編集を務める[3]。また、この頃マルクス・レーニン主義へと傾倒していった。その後1963年にアル・ムハッリル(Al Muharrir)紙、1967年にアル・アンワル紙と渡り歩き[3]、同年パレスチナ解放人民戦線 (PFLP) が設立されると、そのスポークスマンに就任した。1969年、PFLPの週刊誌アル・ハダフの主幹[3]として編集にも携わり、エッセイと論説を書いた。

カナファーニーは、現代アラビア語文学の主要な作家の一人であり、代表的なパレスチナ文学の作家としても認知されている。パレスチナ解放闘争という、故郷と自身の自由の追求という苦闘の中で生まれた彼の作品は、主としてパレスチナの解放闘争を主題とし、しばしばパレスチナ難民としての自身の経験にも触れたものとなっている。

処女作は短編『十二号ベッドの死』(1961年)。『君たちに残されたもの』(1966年)などの小説のほか、『シオニストの文学』(1970年)といった文学評論でも知られる。中でも、短編『太陽の男たち』(1968年)は、現代アラビア語文学の傑作の一つに数えられ、今日に至るまで非常に高い評価を得ている。

1972年7月8日、カナファーニーはレバノンの首都ベイルートで姪とともに、自分の車に仕掛けられていた爆弾の爆発により暗殺された。カナファーニーがPFLPの活動家であったことから、爆発物を仕掛けたのはイスラエルの特殊部隊である可能性が指摘されている。

1961年にデンマーク人の児童人権活動家の女性と結婚、2人の子供がある。

著作

アラビア語圏では、現代エジプトを代表する作家の一人であるユースフ・イドリースの序文が掲げられた3巻の全集が刊行されている。

日本語訳

日本では、他のアラブ人作家と同様に著作の翻訳・刊行数は少なく、パレスチナ文学、ポストコロニアル文学の代表例として採り上げられることもしばしばである。

2005年からアラブ文学者の岡真理によって幾つかの作品が新たに翻訳され始めた。2009年には『日本経済新聞』のコラム「春秋」欄で「ハイファに戻って」が採り上げられたことがきっかけとなり、河出書房新社より『太陽の男たち/ハイファに戻って』が、およそ20年振りに再刊された。

- 『現代アラブ文学選』野間宏責任編集

- [収録作品] ハイファに戻って/占領下パレスチナにおける抵抗文学

- 奴田原睦明・高良留美子訳、創樹社、1974年6月25日発行。 ISBN 978-4-7943-0037-9 (品切れ)

- 『現代アラブ小説全集7:太陽の男たち / ハイファに戻って』

- 『現代アラブ小説全集7:太陽の男たち / ハイファに戻って』(新装版)

- 河出書房新社、1988年12月。ISBN 978-4-309-60187-8 (品切れ)

- 『ハイファに戻って / 太陽の男たち』(新装新版)

- [収録作品] 太陽の男たち/悲しいオレンジの実る土地/路傍の菓子パン/盗まれたシャツ/彼岸へ/戦闘の時/ハイファに戻って

- 黒田寿郎・奴田原睦明訳、河出書房新社、2009年2月27日発行。 ISBN 978-4-309-20518-2

- (上記アラブ小説全集の新装版だが、大江健三郎のエッセイは未収録。

- 『池澤夏樹=個人編集 世界文学全集』Ⅲ-5「短編コレクションⅠ」

- 「ラムレの証言」(岡真理訳)を収録。河出書房新社、2010年7月。ISBN 978-4-309-70969-7

- 『ハイファに戻って / 太陽の男たち』(文庫版)

- 訳者、収録作品は上記と同じ。文庫版解説:西加奈子。河出文庫、2017年。ISBN 978-4-309-46446-6

映画化作品

脚注

出典

参考文献

- 山本薫「パレスチナ文学:ナクバから生まれた言葉の力」臼杵陽・鈴木啓之編『パレスチナを知るための60章』明石書店〈エリア・スタディーズ〉、2016年。ISBN 978-4-7503-4332-7

- 奴田原睦明「単行本版解説」ガッサーン・カナファーニー『ハイファに戻って / 太陽の男たち』河出文庫、2017年。ISBN 978-4-309-46446-6

外部リンク

- NPO前夜(「季刊 前夜」に「ガザからの手紙」、「スロープ」、「ラムレの証言」などのカナファーニー作品の岡真理による翻訳と解題を掲載中)

ハイファに戻って/太陽の男たち (河出文庫 カ 3-1) Paperback Bunko – June 6, 2017

by ガッサーン・カナファーニー (Author), & 2 more

4.5 4.5 out of 5 stars (74)

20年ぶりに再会した息子は別の家族に育てられていた――時代の苦悩を凝縮させた「ハイファに戻って」など、不滅の光を放つ名作群。

===

No comments:

Post a Comment