Museum of Artifacts

ntSopedsor66cobg2au097hr t0901t60187ga3l6hucmf:2O895 m1lmet ·

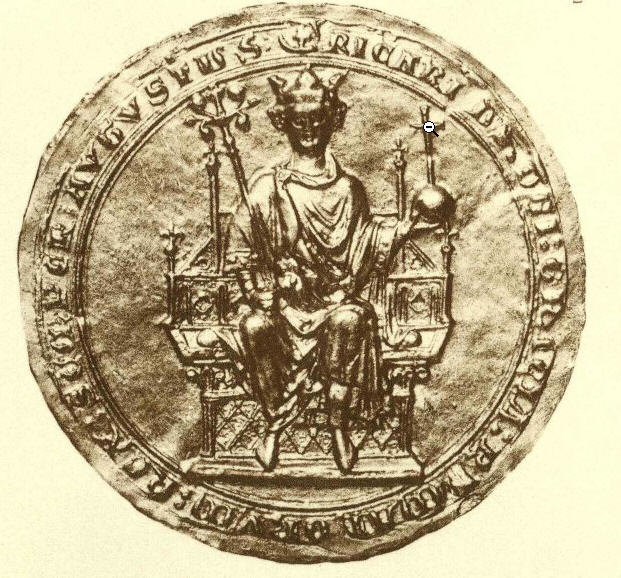

Grotesque male character performing auto-fellatio under the statue of the Archbishop Konrad von Hochstaden, City Hall of Cologne (Germany), circa 1406

All reactions:38K38K

4K comments

7.9K shares

Konrad von Hochstaden Explained

6/6/2017

2 Comments

In the middle ages, the viceroy of God was the most weighty person. The pope was so vigorous so that he was able to depose sovereigns of the Holy Roman Empire, and one of them was even forced to beg in front of the Roman bishop and ask for forgiveness. However, not only the heads of catholic church stood out from the environment of clerics, there were still persons who bequeathed their footstep. Let's go discuss one of the most interesting of them this time.

Mr. Konrad von Gochstaden was a child of the canon of the Cologne cathedral, the temple which Konrad was going to redesign at the summit of his weight. No information left about his young years. We don't also imagine for sure in which year von Gochstaden was born. However, already in year 1216 he was named canon, and ten years later the pastor of the cathedral in Cologne. While the years of his ministry, the guy gained the reputation of an uncompromising and rough person. Some time later the bishop of Cologne expired, and the clergy in the cathedral elected Konrad without doubt. The guy immediately rushed to the work, seized the stuff and encounter several times with local dukes, who wished him to avert reigning lonely in Cologne. After all, when this men suppressed sovereign rulers, the townspeople exhilarated and share a bit weight of the aristocracy, while the practically self-governing area moved under the rule of the priest.

Soon the von Gochstaden and the pope had a disagreement. When the death of bishop of Mainz occurred, the public insisted von Gochstaden to be named on the seat, while the pope prevent him sharing several important regions simultaneously, and after that even revoked Konrad's title of legate in Germany. After falling off in the relationship between the couple, the term between the archbishop and Holy Roman Emperor Wilhelm also fell. Von Gohstaden did not give up, and wait for Wilhelm's decease. In the election campaign of the further Holy Roman sovereign, the man sold the vote for a huge quantity of money to the brother of English king Henry III. As a outcome, Richard took the position of Emperor, and in a short period Konrad solemnly place a wreath on Richard's head. But von Gochstaden is also famous for his statue on Cologne city hall, which pleasant citizens trimed after his death. The masterpiece raises on a sphere depicting autofellation, which means an action when a person caresses own pecker with his mouth. It's a strange work, isn't it?

===

Konrad von Hochstaden

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2023) |

Konrad von Hochstaden (or Conrad of Hochstadt) (1198/1205 – 18 September 1261) was Archbishop of Cologne from 1238 to 1261.[1]

Konrad was a son of Count Lothar of Hochstadt, canon of St. Maria ad Gradus and of the old Cologne Cathedral,[1] and Mathilde of Vianden. His date of birth is unknown, and nothing is known of his early youth. In 1216 he became incumbent of the parish of Wevelinghoven near Düsseldorf; in 1226 he was canon and, some years later, provost of the cathedral of Cologne. After the death of Heinrich von Müllenark (26 March 1238) the cathedral chapter elected Konrad Archbishop of Cologne. He received the archiepiscopal insignia from the Emperor Frederick II at Brescia in August of the same year. The following year, on 28 October, he was ordained priest and consecrated archbishop by Ludolf von Holte, Bishop of Münster.

For the first few months of his reign, the new archbishop sided with the emperor in his conflict with Pope Gregory IX, but for unknown reasons went over to the papal party shortly after the emperor's excommunication (12 March 1239). The whole temporal administration of Konrad was a series of struggles with neighbouring princes and the citizens of Cologne, who refused to acknowledge the temporal sovereignty of the archbishop over their city. Konrad was generally victorious, but his often treacherous manner of warfare has left many dark spots on his reputation. When Pope Innocent IV deposed Frederick II (17 July 1245), it was chiefly due to the influence of Konrad that the pope's candidate, Henry Raspe, Landgrave of Thuringia, was elected king; when Henry died after a short reign of seven months (17 February 1247), it was again the influence of Konrad that placed the crown on the head of the youthful William[2] of Holland.

In recognition of these services, Pope Innocent made him Apostolic legate in Germany (14 March 1249), an office which had become vacant by the death of Archbishop Siegfried III of Mainz, five days previously. The clergy and laity of Mainz desired to have the powerful Konrad of Cologne as their new archbishop. Konrad seems to have secretly encouraged them, but for diplomatic reasons referred them to the pope, who kindly but firmly refused to place the two most important ecclesiastical provinces of Germany under the power of one man.

Shortly after this decision the hitherto friendly relations between Pope Innocent IV and the archbishop ceased, and in April 1250, the Apostolic legation in Germany was committed to Pierre de Colmieu, Bishop of Albano. At the same time began Konrad's estrangement from King William, which finally led to open rebellion. With all the means of a powerful and unscrupulous prince, Konrad attempted to dethrone William and probably would have succeeded had not the king's premature death made the archbishop's intrigues unnecessary. After the death of King William (28 January 1256), Konrad played an important role in the election of the new king. He sold his vote for a large sum to Richard of Cornwall, brother of Henry III of England, and crowned him at Aachen on 17 May 1257. This was the last important act of Konrad. He died on 28 September 1261 and is buried in the cathedral of Cologne, of which he laid the cornerstone on 15 August 1248.[1]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Ballester, José María; Europe, Council of (2000-01-01). Sustained Care of the Cultural Heritage Against Pollution: Based on Proceedings of the Seminar Entitled "Sustained Care of the Cultural Heritage Against Deterioration Due to Pollution and Other Similar Factors: Evaluation, Risk Management and Public Awareness". Council of Europe. ISBN 978-92-871-4233-7.

- ^ Caers, Bram; Visscher, Mark (2018). "The Illuminated Brabantsche yeesten Manuscripts IV 684 and IV 685 in the Royal Library of Belgium: An Unfinished Project of Brabantine Historiography. Description, List of Illustrations and Index of Persons Depicted". In Monte Artium. 11: 7–35. doi:10.1484/J.IMA.5.116486. hdl:10067/1565380151162165141. ISSN 2031-3098. S2CID 166178781.

Cologne City Hall

The City Hall (German: Kölner Rathaus) is a historical building in Cologne, western Germany. It is located off Hohe Straße in the district of Innenstadt, and set between the two squares of Rathausplatz and Alter Markt. It houses part of the city government, including the city council and offices of the Lord Mayor.[1] It is Germany's oldest city hall with a documented history spanning some 900 years. The history of its council during the 11th century is a prominent example for self-gained municipal autonomy of Medieval cities.[2]

Today's building complex consists of several structures, added successively in varying architectural styles: they include the 14th century historic town hall, the 15th century Gothic style tower, the 16th century Renaissance style loggia and cloister (the Löwenhof), and the 20th century Modern Movement atrium (the Piazzetta). The so-called Spanischer Bau is an extension on Rathausplatz but not directly connected with the main building.

History[edit]

The City Hall is located on the site of the former Ancient Roman Praetorium, which until the year 475 was seat of the Roman Governor of Germania Inferior. Merovingian kings are known to have used the praetorium as a regia until 754, however the building was ultimately destroyed by an earthquake in the late 8th century.[3] Under Hildebold of Cologne, the city was elevated from a bishop's to an archbishop's see in 795, and the area around the former praetorium has become home to both a group of wealthy Patrician merchants and Cologne's Jewish community, many of whom were under immunity granted by the king.

With Emperor Otto I's younger brother Bruno the Great becoming archbishop in 953, the Ottonian dynasty established a secular government by an ecclesiastic archbishop. This abundance of power in Medieval Europe was in stark confrontation to the emerge of emancipating burghers: armed conflicts in 1074[4] and 1096 were followed by the formation of a commune and first municipal structures as a basis for urban autonomy. In order to consolidate their economic and political rights, Cologne burghers established fraternities and trade guilds (most notably the Richerzeche). In the 1106 war of succession between Emperor Henry V and his father Emperor Henry IV, they took deliberate opposition to the archbishop, after which they gained benefit in regards to the city's territorial expansion over the following years. As – at the time – one of Europe's busiest trading ports and largest city in Germany, the population of Cologne gradually changed from a mainly feudal society to free citizens. Documents from the years 1135 and 1152, recorded "a house in which citizen convene",[5] referring to the first established council hall, at the location of today's town hall. The coat of arms of Cologne, first mentioned in 1114, is Europe's oldest municipal coat of arms.

By 1180, the citizens of Cologne won a legal battle against Philip I, Archbishop of Cologne, for another extension of Cologne's city walls. With the Battle of Worringen fought in 1288, Cologne became independent from the Electorate and on 9th September 1475 officially gained Imperial immediacy as a free imperial city. In 1388 Pope Urban VI signed the charter for the University of Cologne, Europe's first university to have been established by citizenry. On 14th September 1396 the constitution of Cologne came into effect and the Cologne gaffs and guilds (Gaffeln and Zünfte) assumed power in the council. Following the tradition of Roman consuls, the council was headed by two elected Burgomasters (Mayors) until the year 1797, when council and constitution were replaced by the Napoleonic and later code civil. Since 1815 the city council is led by one Oberbürgermeister (Lord Mayor).

During the bombing the entire city hall was destroyed except for the front portion and part of the tower, the remaining part being rebuilt in modern style.

Buildings and building components[edit]

Historic Town Hall[edit]

The oldest part of today's City Hall is the so-called Saalbau (i.e. roofed hall building), which replaced a previous Romanesque style council building of 1135 on the same location. The Saalbau dates back to 1330 and is named after the Hansasaal, a 30,0 by 7,6 metres large and up to 9,58 metres tall assembly hall and core of the entire Rathaus. The hall is named after the Hanseatic League, which held an important summit in it on 19. November 1367. Noteworthy are stone figures of the Nine Worthies, the Emperor and the Privileges.

Tower[edit]

Commissioned by the Cologne guilds on 19 August 1406, the Gothic-style Ratsturm (Council tower) was built between 1407 and 1414 and reaches a height of 61 metres. It consists of five storeys and the so-called Ratskeller (Council cellar). Its purpose was mainly to store documents, but one of the lower floors also housed the Senatssaal (i.e. hall of the Cologne Senate). While being heavily damaged during the bombing of Cologne in World War II, the tower – including the many exterior stone figures – has been restored entirely. Curiously, beneath the statue of Konrad von Hochstaden, there is a grotesque male character performing autofellatio.[6] Four times daily, a carillon (German: Glockenspiel)[7] is played by the tower's bells.

Loggia[edit]

The Rathauslaube – as the Renaissance style Loggia is called – is a replacement of a previous loggia on the same location. The council initiated a lengthy design process in 1557, which lasted until 1562. In July 1567 the council approved the design by Wilhelm Vernukken from Kalkar to be built, with construction lasting from 1569 to 1573.[8] The loggia consists of a 2-storey, five-bay long and two-bay deep arcade, which functions as entrance to the councils main hall (Hansasaal) at ground level, and as balcony for the main hall on the upper floor. The balcony was used for public speeches throughout the year.

Piazzetta[edit]

Likened to a small piazza with various building making up the perimeter walls, the 900 square metre large and 12.6 metres tall atrium was built during the postwar restoration of the historic town hall.

Spanischer Bau[edit]

Built on the North-western side of Rathausplatz in the years 1608 to 1615, the city council commissioned the originally Dutch Renaissance style building for meetings and celebrations. The name emerged in reference to Spanish delegates at the building during the time of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). However it was not in official use before the 19th century. After having been heavily damaged in 1942, the building was completely rebuilt in 1953.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Most of the city administration has been moved to the so-called Stadthaus (i.e. city house) in Deutz.

- ^ Hermann Jakobs: Verfassungstopographische Studien zur Kölner Stadtgeschichte des 10. bis 12. Jahrhunderts, Köln, 1971, p. 49-123

- ^ Ulrich Krings and Walter Geis: Köln: Das gotische Rathaus und seine historische Umgebung, J.P. Bachem Verlag, Köln, 2000

- ^ Annals of Lambert of Hersfeld: The 1074 uprising against Anno II

- ^ from Latin: "domus in quam cives conveniunt"

- ^ "Konrad von Hochstaden Explained". Notes about history. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- ^ City of Cologne: Das Glockenspiel im Rathausturm

- ^ Isabelle Kirgus: Die Rathauslaube in Köln (1569–1573), Bouvier, Bonn, 2003

External links[edit]

- City of Cologne: Description of the history and architecture of the building (in German)

- Cologne Tourism: Historic Town Hall (in German, English, Spanish, and French)

No comments:

Post a Comment