DPRK lies and videotape: North Korea's "investigative" journalism | NK News

DPRK lies and videotape: North Korea’s “investigative” journalism

Cloaked in the language of objectivity, state media hits back at international condemnation

SHARE

Sandra Fahy September 14, 2016

Image: North Korea - Cameraman by Roman Harak on 2010-09-06 01:43:38

Photography and film have long been associated with holding a mirror to oppression and injustice. Think of Claude Lanzmann’s heartbreaking nine-hour documentary film “Shoah,” or Joshua Oppenheimer’s “The Act of Killing.”

The North Korean human rights campaign has gathered swift momentum in the last ten years, through efforts of international non-governmental organizations, but also through its use film and documentaries. The greatest push has come from the United Nations Commission of Inquiry, which resulted in a mammoth report, based on the testimony of 200 experts and survivors, confirming the existence of widespread and systematic crimes against humanity in North Korea.

The testimonies were recorded and placed in the public domain, the video and audio is available to anyone with internet access.

But where justice seekers seek to document atrocities to avenge wrongs, the reverse is also taking place: from ISIL to Boko Haram to the DPRK, perpetrators are reaching out, using media to galvanize support, promote their ideology, and project their power.

Since the public and high-profile testimonies of North Korean defectors at the United Nations, North Korea has hit back, primarily through state media, in the form of print, television news, and “investigative documentaries.”

Not surprisingly, these documentaries and news broadcasts refute allegations of abuses and denounce defectors. Totaling dozens of hours, the documentary and news broadcast footage casts a wide net.

HITTING BACK

There are plenty of examples. Justice Michael Kirby – the Australian high court judge, and leader of the commission – was slandered for being gay, the United Nations was characterized as a puppet of the United States, Penguin publishing house is doomed to economic failure for its release of the memoirs of defector, and all defectors are traitors and liars paid by the United States to slander the country and its government.

Defector Yeon Mi Park – a frequent target of state media ire | Photo by Gage Skidmore

Defector Yeon Mi Park – a frequent target of state media ire | Photo by Gage Skidmore

But what can be learned about human rights violations through study of its content and construction? What objects, people and places are commonly contained in the videos? Photographs figure prominently, as do the family members, friends, and landscapes local to the defector.

Since the public and high-profile testimonies of North Korean defectors at the United Nations, North Korea has hit back, primarily through state media, in the form of print, television news, and “investigative documentaries.”

The narrative uses intense berating character description told from the point of view of friends and relatives. There is extensive manipulation of tone of voice, coaching by the interviewer off-screen, and teleprompter use.

The videos employ methods of authentic documentary making. For instance, they often take an approach not unlike other investigative journalists: they interview the “man on the street,” they use audio cues to indicate typing and documentation for the investigation, they use voice over, and embed UN film-footage stills within the film.

Shin Tong Hyuk | Defector Photo by US Mission Geneva

Shin Tong Hyuk | Defector Photo by US Mission Geneva

SERVING AN AGENDA

But these videos boldly disregard norms associated with reliability, trust and rigor, through editing, at the post-production phase, with quick, unusual jump-cuts.

They also achieve this at the level of the narrative itself. Multiple people are interviewed (often the family, friends and co-workers of former defectors), but all share a singular interpretation of the defector as evil.

The narrative uses intense berating character description told from the point of view of friends and relatives. There is extensive manipulation of tone of voice, coaching by the interviewer off-screen, and teleprompter use.

Key details of defectors’ accounts which implicate the state are neatly explained as due to the clumsy mishaps and reprobate character of the defector – the latest example of this being their brash lies to the United Nations. The multiplicity of voices is singularly shocked and disgusted, and the videos create a looped world onto itself, like a Mobius strip: the structure blurs the inside and outside seamlessly such that there is no inside and outside, while feigning to reveal it all.

The lives of defectors are told through their bodies. Scholars have identified that growth stunting in North Korea is starkly demonstrative of socioeconomic inequalities between the North and South. Rates of tuberculosis and multi-drug resistant tuberculosis in North Korea and among defectors is markedly higher than rates in South Korea.

Photo by orangetruck1

Photo by orangetruck1

BODY POLITICS

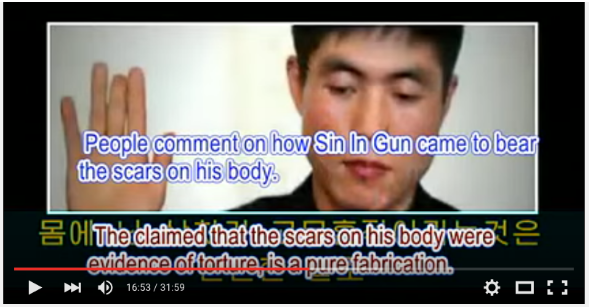

During the Commission of Inquiry was recording testimonies, defectors identified torture scars and other injuries on their bodies as they narrated the experiences that put them there.

Key details of defectors’ accounts which implicate the state are neatly explained as due to the clumsy mishaps and reprobate character of the defector

The following is a still from the documentary “Reveal the True Identity of the Human Trash Sin Tong Hyuk.” In the image, you can see the right hand of the tip of his middle finger is missing.

At the UN, Shin explained how the tip of his finger was removed from him. While carrying a large sewing machine up a set of stairs on his back his hands lost their grip. The machine fell and was damaged. As punishment, Shin was at risk of losing his entire hand, but the guard cut off the tip of his middle finger.

Photo credit: Stimmekoreas

Photo credit: StimmekoreasIn the film, the wound is emptied of meaning as a signifier of crimes against humanity, and replaced with meaning as evidence of Shin’s deceit; evidence of the UN’s deceitful agenda.

The body of the defector and his words are not outside of the political debate, but central to its operation. Just as torture unmakes and remakes the world of victims, state violence continues that cycle of abuse. As long as the survivor surfaces in the public realm to point an accusatory finger at the DPRK, the DPRK will empty their testimony of meaning domestically, and furnish it with their narrative.

The voice of the defector, delivered to an international audience, opens the possibility for North Korea to reach him again and to continue to abuse them – almost an inevitable re-victimization a survivor faces when he dares to speak his experience.

RELIVING THE TRAUMA

In pointing to the scars on his body, he is at once addressing the story of his abuse and his abuser: the abuse belongs to the abuser, as the scars belong to him. That relationship is made perversely public, which is agonizing to the survivor, and yet in a different way agonizing to the state. They are brought into a biopolitical, humiliatingly public struggle for recognition of human over sovereign rights.

The voice of the defector, delivered to an international audience, opens the possibility for North Korea to reach him again bio-politically and to continue to abuse them

On the level of forensic examination of the video, the following clip indicates how the DPRK disregards norms associated with reliability, trust and rigor. They do this through editing, at the post-production phase, with quick, unusual jump-cuts.

In the scene below, Mr Choi is denouncing his brother. This section appears here unedited by me; it is instead a slice of the film as it appears in the documentary. Focus on the jump-cuts, and follow the tone of voice.

By even the most basic standard, the video appears low-quality, low-budget, and amateur. Looking forensically, the narrative voice is constructed very deliberately. This pattern repeats throughout North Korea’s documentaries. In each, there are dozens of quick jump cuts where the cutting and pasting of footage patches scenes as if they occurred sequentially.

RE-FRAMING THE NARRATIVE

This pattern repeats throughout North Korea’s documentaries. In each, there are dozens of quick jump cuts where the cutting and pasting of footage patches scenes as if they occurred sequentially, when they have not. This is evident not only in the cuts, but also in the changes marked by different tones of voice from the same speaker within the same sentence, different light changes in the room due to the passage of time, and edits that happen mid-sentence at points where the speaker says “however” and “but.” The editors are telling the story in post-production.

But don’t the videos undermine their own credibility through the obvious and heavy-hand of editing? Maybe the cutting and splicing would be accepted as though the editors are doing me a favor by taking out the blunders and mistakes. Does this engender a sense of being “minded” or “taken care of” by a message that has been clarified and streamlined through this deliberate construction?

The editors are telling the story in post-production.

What is strikingly totalitarian about this method is that it takes a negative (the manipulation of fact) and turns it into a positive (this is streamlined for ease of understanding): craft is sacrificed in favor of message.

We have long known that North Korea is a theater state: these films are a powerful manifestation of that.

RELATED ARTICLES

The movement to return the Japanese wives of Zainichi repatriates from N. Korea

About the Author

Sandra Fahy

Sandra Fahy earned her PhD in Anthropology at SOAS, University of London in 2009. She held post-doctoral fellowships at EHESS in Paris and USC in Los Angeles, before taking up a position in Anthropology at Sophia University in 2013. Her first book Marching through Suffering: Loss and Survival in North Korea (Columbia University Press, 2015) examines how North Korean famine survivors understood the food crisis and concomitant political violence. In addition to several peer-review academic articles, she also has also written policy recommendation pieces on humanitarian preparedness for internal migration in North Korea (Asia Policy, 2015) and rights-based approaches to health in the DPRK (Harvard Journal of Health and Human Rights, 2016). She is finishing a second book about Human Rights and North Korea.

No comments:

Post a Comment