HISTORY

Japan in 2020: Making Sense of Professors in Overwhelmingly Insular American Universities

Published

1 year agoon

January 4, 2020

I sympathize with my Japanese friends when they wonder what American professors could be thinking.

The American professors sneer at the egalitarian entrance examinations to the national universities, and urge the schools to adopt sex quotas. They cheer the Kaiho domei’s accusations of anti-dowa racism. They instinctively accept the most implausible Korean claims about forced abductions and sexual slavery in the wartime brothels. They accept equally evidence-free claims about forced labor to the coal mines. And about Prime Minister Shinzo Abe? For anyone who might venture anything positive about him, they display utter contempt.

There are reasons for all this, and they go to the place universities occupy within the dangerously polarized world of American politics. Most basically, the prominent humanities and social science departments are places of near-total political conformity. Overwhelmingly, the faculties support the Democratic Party, and generally support the left fringe of the Party at that.

Racial preferences have been a key component of the Democratic platforms for at least several decades — hence, the instinctive sympathy for the Kaiho domei. Sex preferences have been almost as central, and for almost as long — hence, the disdain for egalitarian admissions.

The instinctive professorial sympathy for the Korean claims is more complex, and goes to the current agenda in American humanities (and sometimes social science) departments. The scholars most apt to study Japan tend to come from humanities disciplines, like anthropology, history, and literature. Within these departments, faculty focus increasingly on racism, sexism, and imperialism. Korean activists claim that racist and sexist Japanese soldiers kidnapped young girls for the comfort stations. They claim that imperialist Japanese soldiers drafted Korean men at bayonet-point into the Japanese coal mines. In both accounts, they tell a story that fits perfectly the standard template by which many humanities scholars instinctively view the world.

The political conformity within American universities makes the environment overwhelmingly insular. Within the humanities and social sciences, professors will seldom see articles by someone who might question their political preferences. They will seldom encounter a workshop where the speaker might contest their partisan assumptions. They will seldom meet either a colleague or a graduate student who does not share their political instincts. The only Republicans a professor might meet are the occasional outspoken undergraduate or the local auto mechanic.

These are testable empirical propositions — which scholars have tested. A scholar interested in the issue can approach it in two general ways: through campaign contributions or through voter registration records.

Political donations are public information in the U.S. A researcher can easily locate the national data set online and examine the political contributions made by faculty members at a university. In many states, moreover, voters can declare their party preference when they register to vote. In states that make these records public, a researcher can search the party affiliation of those faculty who live in the communities near the university.

For example, one group examined contributions made by professors at several prominent universities during the 2012 elections. The following table gives the total contributions by university employees, followed by the percentage of those contributions that went to Democratic candidates:

CONTRIBUTIONS BY UNIVERSITY EMPLOYEES

University Total % Democrat

Yale $567,789 97%

U Chicago 686,253 96

Cornell 646,121 95

UC Berkeley 3,144,466 93

Columbia 1,109,513 90

U Penn 693,455 89

Harvard 2,488,429 85

U Michigan 649,822 85

MIT 649,097 85

Source: Center for Responsive Politics, Top Contributors to Federal Candidates, Parties, and Outside Groups, OpenSecrets.org, visited Apr 1, 2014.

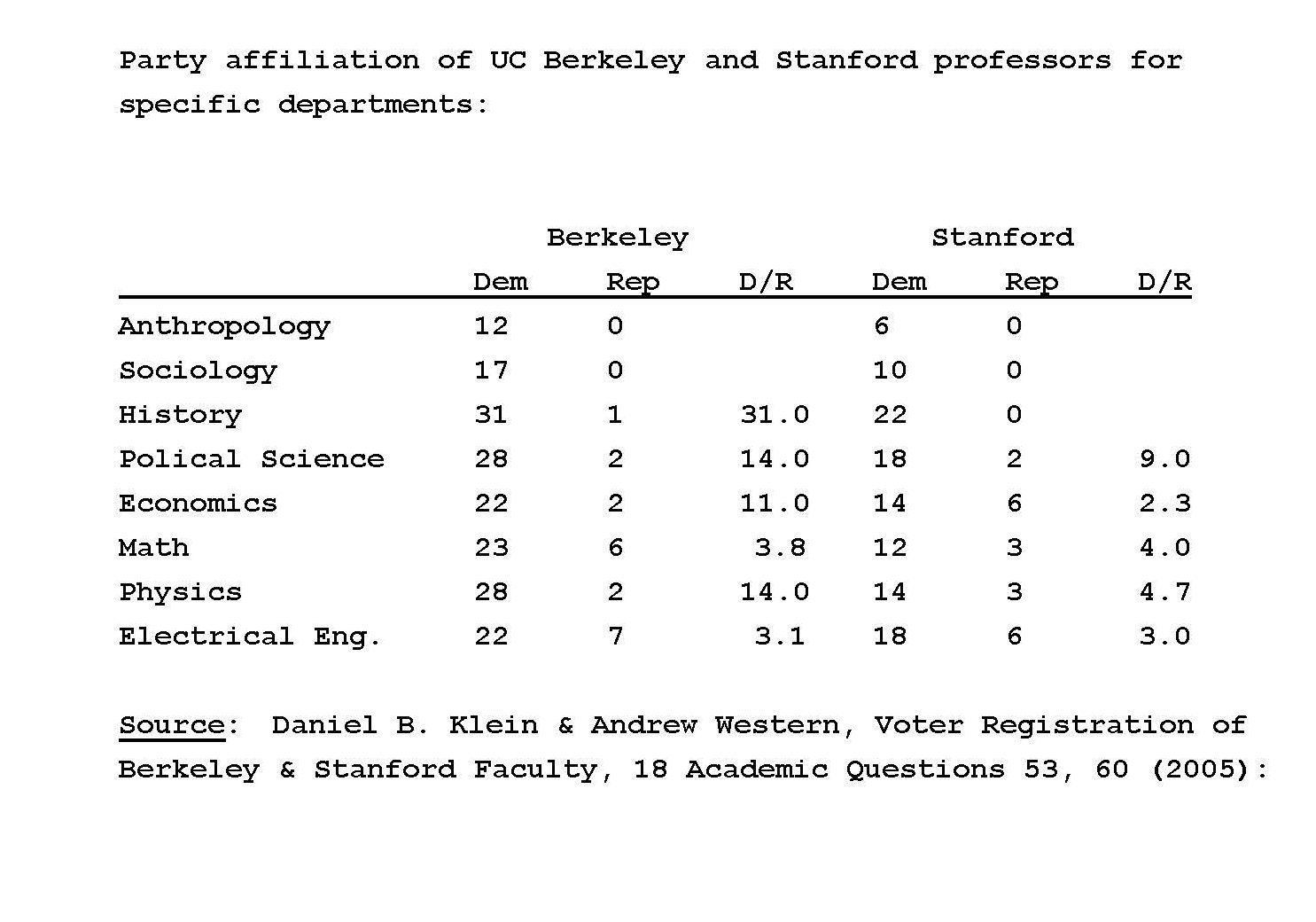

Similarly, in 2005 two professors published a study in which they used voter registration records to explore the party affiliation of UC Berkeley and Stanford professors. Consider several of the more important departments:

Consider the disciplines whose scholars most often write about Japan: anthropology, sociology, history, and political science. All of these departments are overwhelmingly Democrat. A not unreasonable worry for a Republican student considering graduate school in anthropology, sociology, or history would be that he simply will not be hired in a top department.

These tables are for 2012 and 2005. There is good reason to think matters have become far more partisan since those years. Barack Obama was a polarizing president. He tried to govern from what was then the fringe left, and did not offer to compromise. When a congressional stalemate ensued, he implemented his policies by regulation.

By 2016, many conservatives saw the country as lurching dangerously to the left. As Hillary Clinton seemed inclined to carry forward the Obama agenda, they voted for Donald Trump — for the simple reason that he would not continue the Obama programs. Obviously, Trump has become an even more polarizing president than Obama.

Eight Obama years and four Trump years have created tensions so severe that they have turned American universities into dangerously intolerant places. If Abe has managed to build a strong alliance (and possibly even a friendship) with Trump, for many university faculty this itself is reason to despise Abe.

Living and working within ideologically hermetic worlds, many professors cannot understand how anyone thoughtful would vote for Trump. Unfortunately for my thoughtful Japanese friends, neither can they understand why any Japanese would support his apparent friend Abe.

Author: J. Mark Ramseyer

Mark Ramseyer is a professor at Harvard Law School in the United States.

No comments:

Post a Comment