https://librarysearch.adelaide.edu.au/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma9928228841801811&context=L&vid=61ADELAIDE_INST:UOFA&lang=en&search_scope=all&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=Everything&query=any,contains,Baruch%20Kimmerling&offset=0

View Table of Contents

CONTENTS

Expand ToC

Introduction: A Guerilla Fighter for Ideas

PART I: AND THIS IS THE STORY

Chapter 1. So that the child would not understand

Chapter 2. Fleeing

Chapter 3. Fantasies

Chapter 4. Ariel and Michael

Chapter 5. The Transylvania was not the Roslan

Chapter 6. The Library

PART II: CAMPUS

Chapter 7. At the Dormitories

Chapter 8. Adam

Chapter 9. My Body's Betrayal

Chapter 10. Diana

PART III: THE STRUGGLE OVER THE PARADIGM

Chapter 11. March 6th, 1969

Chapter 12. The Department

Chapter 13. On Zionism

Chapter 14. Between Boston and Toronto

Chapter 15. On One Hand and on the Other Hand

Chapter 16. Ancestors’ Sepulchers and Sons’ Graves

Chapter 17. About The Nuclear Issue

Chapter 18. This Constitution is Prostitution

Chapter 19. The Mouse that Roared

Chapter 20. State Option

Chapter 21. The Right to Resist the Occupation

Chapter 22. Kulturkampf

Chapter 23. Politicians

Chapter 24. Between Despair and Hope

In Lieu of a Conclusion: Question Marks

Click here to select your preferences

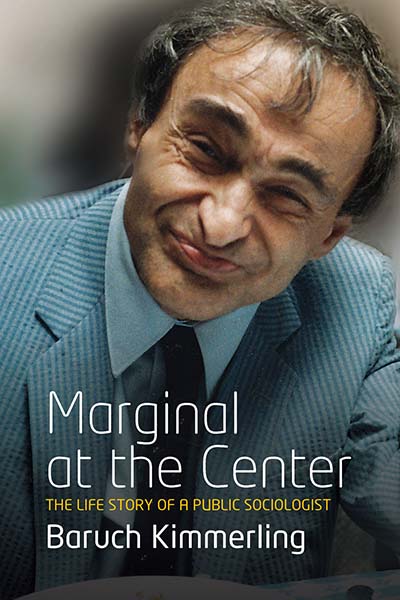

MARGINAL AT THE CENTER

The Life Story of a Public Sociologist

Baruch Kimmerling

Translated from the Hebrew by Diana Kimmerling

258 pages, 13 illus., bibliog., index

ISBN 978-0-85745-720-2 $34.95/£27.95 / Pb / Published (June 2012)

eISBN 978-0-85745-751-6 eBook

https://doi.org/10.3167/9780857457202

Buy Paperback$34.95

Buy eBook$34.95

View CartYour country: Australia - edit

Request a Review or Examination Copy (in Digital Format)

Recommend to your LibraryAvailable in GOBI®

REVIEWS

“What a wonderful read Baruch Kimmerling’s memoir is! [it takes] us from Kimmerling’s childhood in Romania, including his dramatic escape in 1944 on a horse-drawn carriage dodging a roundup of Jews in his hometown, to his final months in Jerusalem. His account, expertly translated by his wife Diana, is not a chronological story but one in which personal vignettes serve as launching pads for explorations of Israeli society and academia.” · The European Legacy: Toward New Paradigms

“Some of the chapters… which describe his life as a public sociologist in Israel-Palestine, could well be read by sociologists in Northern Ireland, South Africa and other conflict zones as a lesson in how to use sociology to try to make a difference.” · Magazine of the British Sociological Association

DESCRIPTION

A self-proclaimed guerrilla fighter for ideas, Baruch Kimmerling was an outspoken critic, a prolific writer, and a “public” sociologist. While he lived at the center of the Israeli society in which he was involved as both a scientist and a concerned citizen, he nevertheless felt marginal because of his unconventional worldview, his empathy for the oppressed, and his exceptional sense of universal justice, which were at odds with prevailing views.

I did not pave roads and I did not dry up swamps. I was not a pioneer, a warrior,

or even a military officer. I did not establish settlements and I did not build

industrial plants. I wasn’t exactly a Holocaust survivor or a secret agent. I

neither founded nor wrecked political parties. I was never even a member of

one or a public figure. I wasn’t a pop star, a cultural hero, an actor in the theater,

or a player in a stadium. I am not a poet, an author, a sculptor, or a painter. I am

certainly not a dancer. So, what actually did I do that would justify the writing

of an autobiography and, even more so, its reading?

I was, and still am, primarily a producer, critic, disseminator and examiner

of ideas as well as someone who has been trying to shelve several ideas which,

according to my values, should be abandoned. At the very least, I tried to argue

with their advocates and I like to think of myself as a guerilla fighter for ideas.

However, an idea must also pass the reality test; that is, it is necessary to

examine, using different methods, how people, groups, and organizations act

and react in real life and to ask how their actual practice compares to the norms

and ideologies according to which they claim to act. What am I, then? I

research societies using a comparative approach, a discipline known in public

as “sociology.” But sociology also includes the study of history, culture, and

economics as well as the examination of ideas, the investigation of social

movements, states and the relationships between them, and all patterns of

activities of groups of men and women and their identity.

Sociology may be classified in many ways. For the purpose of this book, I

will distinguish between academic and public sociology, a concept that is still

not widely known in Israel. The academic sociologist whose credentials are

well established is secluded in the academic ivory tower and his goal is to

advance human knowledge. Whether his findings will ever be used is not a

major concern of his and his main audience is primarily his students and

colleagues—which is not insignificant. Indeed, he may, from time to time,

emerge from the tower to talk to a larger public, mostly when he is challenged

by other social agents such as the media, or when he is called on by the public

relations department of the university that employs him to support some cause.

But these are not his main concerns.

2 Marginal at the Center

The “public” sociologist (or the intellectual) must be an academic sociologist

who is obliged, no less than his academic colleague, to succeed in the area of

research and observe the professional ethos. At the same time, in addition to his

research, he must also try to influence, with the help of his ideas, the public

political, social, economic, and cultural agenda, primarily through the creation

and distribution of alternative ideas capable of replacing those that are currently

dominant. He also aims to correct what seems to him to be flawed in his own

society. The public sociologist sees these activities as part of his duty. The most

prominent example, in my opinion, is that of the French sociologist and

philosopher Raymond Aron. Aron, after serving in de Gaulle’s Forces Françaises

Libres, returned to France and became a professor of Social Thought and

Political Sociology at the Sorbonne (and a few other universities in France).

At the same time, over a period of thirty years, he wrote a column for the

newspaper Le Figaro. He and Jean-Paul Sartre were of the same vehement

opinion about the need to withdraw the French settlers from Algeria. They did,

however, differ in their philosophical paradigms and in their ideological

approach. Aron opposed Sartre’s existentialism and was a rationalist and a

humanist and, in contrast to Sartre and most of the French intellectuals of that

period, did not sympathize with Communism and did not support the Soviet

Union. As a result, he was unjustifiably considered a conservative.

It is unnecessary, I believe, for me to state that I see myself as a “public”

sociologist, as will be seen later, primarily in part four of this book.

The creation of an idea is a strange process that I myself do not fully

understand, even when it occurs in my own mind. Furthermore, I did not find

satisfying explanations for the phenomenon of intellectual creativity. I am not

referring here to a single concept, like those written by a copywriter, but rather

to the creation of a complex world of content such as a new paradigm. A paradigm contains a system of criteria that permits an examination in the field that

either supports or rejects accepted opinions such as, for example, the one

claiming that Israel is not a militaristic society. This process includes the

precise identification of the types of militarism that do and do not exist in Israel

through a quite innovative assumption that militarism does not have a singular

and uniform social pattern. Rather, it changes its form in different places and

from one period to another and throughout its various forms, it is possible

to see a common trait—the over-reliance on the use of force in an attempt to

solve social and political problems. Among the public at large and even among

many researchers, there is a tendency to relate to only one of the many forms

of militarism—the Praetorian type, in which the army comes out of its barracks

and the military officers seize power. The fact that this obviously did not occur

in Israel is convenient for those denying the existence of Israeli militarism.

However, all those researchers and thinkers who are, presumably, concerned

about Israel’s “good name” as a democratic state usually highlight, with praise,

the involvement of the military and the defense establishment in general in

almost all aspects of life in Israel—culture, education, economics and, of course,

politics. “The whole nation is an army,” is frequently stated with pride. A

Introduction 3

researcher and close friend of mine once claimed that the fact that most Jewish

men in the prime of their active life serve first in the army and then spend at

least one month a year in the reserves “civilianizes” the army by making it

transparent, accessible, and free of myths to most civilians. When I tried to

turn the argument upside-down by asking whether it would not be more

reasonable to assume that the extended period of time that the Israeli man (and

also, to a lesser extent, the Israeli woman) spends in the rigid military framework

may burn into his consciousness the values of army and power, or what the

professional literature calls the “military mind,” I did not receive either a theoretical or an empirical answer to my question. Therefore, I identified two interconnected types of militarism that are found in Israel: cultural militarism,

which turns the army and its symbols into a central component of the national

culture and identity; and cognitive militarism, which causes people to think in

militaristic and aggressive terms without even being aware of it. The problem

is not that the army is militaristic, since this is the nature and essence of an

army, but rather that the bulk of civilian society is also militaristic.

It is not, however, the intention of this introduction to deal with Israeli

militarism but rather to use it as an example of the development and metamorphosis of an idea and a genuine sociological issue that I researched and promoted. This idea gradually developed and matured within me over almost seven

years, during which time I criticized and dismantled the dominant thought on

the subject through discussions and debates with friends and colleagues and

sometimes, while lecturing at the university, through arguments and dialogues

with students. I am indebted to my students for several stages in the development of various ideas. In this case, for example, I owe a debt to the female

student who said in one of the lessons “We think army” and another student

who stated that “Even when we make peace, we do it using power.”

The more an idea is accepted, the more ungrateful it becomes. After a while,

it enters the public domain and severs itself from you altogether as if you were

not its “father-begetter.” I often hear many of my ideas flying around the public

sphere in the country (and some even in the world at large)—such as, for

example, Israel as a frontier society or as a state with multiple socio-political

borders, or the confrontation between the two collective identities “The Land

of Israel” vs. “The State of Israel”—without any attribution or disguised by

another concept. On the one hand, I rejoice when this happens because there

can be no greater triumph for a creator of ideas than the acceptance of his idea

as self-evident. On the other hand, the terrible little demon inside me squeals

and screams, “…but this is my child, mine, mine…” This does not mean that all

my ideas were good, and even when I suspect that they weren’t too bad, that

doesn’t mean that they were accepted. The consolidation of ideas is an ongoing

process of trial and error: primarily error.

Throughout my public writing, I almost never dealt with social topics such

as welfare, but I devoted quite a lot of space to the harm inflicted on the

universities and higher education and from this perspective, I consider myself

an elitist. I barely dealt with subjects regarding social inequalities (except,

4 Marginal at the Center

marginally, in my Hebrew book The End of Ashkenazi Hegemony) not because I

didn’t consider them important, but rather because I suppose that some

“division of labor” must exist in the sphere of public debate and struggle. Apart

from that, I also reasoned that those issues are interdependent and that changes

in the regime of occupation are a necessary precondition for the radical

treatment of problems such as poverty, education (which often functions to

reinforce existing social barriers, especially in the geographical periphery of the

country), the environment, and more.

I believe that it is proper for all human beings to have an absolute equality

of opportunity and self-actualization, and that the state must assist the weak in

the society. These core values lead me to believe that the state is obliged to act

less as a symbol and a realization of the national identity and more as a welfare

state that redistributes the common resources. Nevertheless, I do not classify

myself as a member of the left wing. My personal political identity is that of a

radical humanist. I do, however, find myself in most matters to be close to the

left although I am critical of its ideological stagnation.

This book is a combination of my life story and, briefly, that of family

members from previous generations whom I consider part of my story, together

with the most important expressions of my works both as an academic and a

public sociologist. I was able to mention only a few of the hundreds of articles

that I published in Hebrew and English and the arguments I made; otherwise

I would never have been able to complete this manuscript and no publisher

would have published it. The story does not necessarily unfold in chronological

order, and the connection between the autobiographical sections and the other

content is primarily associative. This structure may make it more difficult for

the reader, but this pattern of thinking is typical of me and is part of me.

Is there any connection between various events in my life and my public

stances? I don’t know and, in truth, this does not concern me.

Jerusalem, February 21, 2007

REVIEWS

“What a wonderful read Baruch Kimmerling’s memoir is! [it takes] us from Kimmerling’s childhood in Romania, including his dramatic escape in 1944 on a horse-drawn carriage dodging a roundup of Jews in his hometown, to his final months in Jerusalem. His account, expertly translated by his wife Diana, is not a chronological story but one in which personal vignettes serve as launching pads for explorations of Israeli society and academia.” · The European Legacy: Toward New Paradigms

“Some of the chapters… which describe his life as a public sociologist in Israel-Palestine, could well be read by sociologists in Northern Ireland, South Africa and other conflict zones as a lesson in how to use sociology to try to make a difference.” · Magazine of the British Sociological Association

DESCRIPTION

A self-proclaimed guerrilla fighter for ideas, Baruch Kimmerling was an outspoken critic, a prolific writer, and a “public” sociologist. While he lived at the center of the Israeli society in which he was involved as both a scientist and a concerned citizen, he nevertheless felt marginal because of his unconventional worldview, his empathy for the oppressed, and his exceptional sense of universal justice, which were at odds with prevailing views.

In this autobiography, the author, who was born in Transylvania in 1939 with cerebral palsy, describes how he and his family escaped the Nazis and the circumstances that brought them to Israel, the development of his understanding of Israeli and Palestinian histories, of the narratives each society tells itself, and of the implacable “situation”—along with predictions of some of the most disturbing developments that are taking place right now as well as solutions he hoped were still possible. Kimmerling’s deep concern for Israel's well-being, peace, and success also reveals that he was in effect a devoted Zionist, contrary to the claims of his detractors. He dreamed of a genuinely democratic Israel, a country able to embrace all of its citizens without discrimination and to adopt peace as its most important objective. It is to this dream that this posthumous translation from Hebrew has been dedicated.

Baruch Kimmerling was Professor of Sociology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His many publications include The Invention and Decline of Israeliness (University of California Press, 2001); A History of the Palestinian People (with Joel S. Migdal, Harvard University Press, 2003); and Clash of Identities: Explorations in Israeli and Palestinian Societies (Columbia University Press, 2008).

Baruch Kimmerling was Professor of Sociology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His many publications include The Invention and Decline of Israeliness (University of California Press, 2001); A History of the Palestinian People (with Joel S. Migdal, Harvard University Press, 2003); and Clash of Identities: Explorations in Israeli and Palestinian Societies (Columbia University Press, 2008).

I did not pave roads and I did not dry up swamps. I was not a pioneer, a warrior,

or even a military officer. I did not establish settlements and I did not build

industrial plants. I wasn’t exactly a Holocaust survivor or a secret agent. I

neither founded nor wrecked political parties. I was never even a member of

one or a public figure. I wasn’t a pop star, a cultural hero, an actor in the theater,

or a player in a stadium. I am not a poet, an author, a sculptor, or a painter. I am

certainly not a dancer. So, what actually did I do that would justify the writing

of an autobiography and, even more so, its reading?

I was, and still am, primarily a producer, critic, disseminator and examiner

of ideas as well as someone who has been trying to shelve several ideas which,

according to my values, should be abandoned. At the very least, I tried to argue

with their advocates and I like to think of myself as a guerilla fighter for ideas.

However, an idea must also pass the reality test; that is, it is necessary to

examine, using different methods, how people, groups, and organizations act

and react in real life and to ask how their actual practice compares to the norms

and ideologies according to which they claim to act. What am I, then? I

research societies using a comparative approach, a discipline known in public

as “sociology.” But sociology also includes the study of history, culture, and

economics as well as the examination of ideas, the investigation of social

movements, states and the relationships between them, and all patterns of

activities of groups of men and women and their identity.

Sociology may be classified in many ways. For the purpose of this book, I

will distinguish between academic and public sociology, a concept that is still

not widely known in Israel. The academic sociologist whose credentials are

well established is secluded in the academic ivory tower and his goal is to

advance human knowledge. Whether his findings will ever be used is not a

major concern of his and his main audience is primarily his students and

colleagues—which is not insignificant. Indeed, he may, from time to time,

emerge from the tower to talk to a larger public, mostly when he is challenged

by other social agents such as the media, or when he is called on by the public

relations department of the university that employs him to support some cause.

But these are not his main concerns.

2 Marginal at the Center

The “public” sociologist (or the intellectual) must be an academic sociologist

who is obliged, no less than his academic colleague, to succeed in the area of

research and observe the professional ethos. At the same time, in addition to his

research, he must also try to influence, with the help of his ideas, the public

political, social, economic, and cultural agenda, primarily through the creation

and distribution of alternative ideas capable of replacing those that are currently

dominant. He also aims to correct what seems to him to be flawed in his own

society. The public sociologist sees these activities as part of his duty. The most

prominent example, in my opinion, is that of the French sociologist and

philosopher Raymond Aron. Aron, after serving in de Gaulle’s Forces Françaises

Libres, returned to France and became a professor of Social Thought and

Political Sociology at the Sorbonne (and a few other universities in France).

At the same time, over a period of thirty years, he wrote a column for the

newspaper Le Figaro. He and Jean-Paul Sartre were of the same vehement

opinion about the need to withdraw the French settlers from Algeria. They did,

however, differ in their philosophical paradigms and in their ideological

approach. Aron opposed Sartre’s existentialism and was a rationalist and a

humanist and, in contrast to Sartre and most of the French intellectuals of that

period, did not sympathize with Communism and did not support the Soviet

Union. As a result, he was unjustifiably considered a conservative.

It is unnecessary, I believe, for me to state that I see myself as a “public”

sociologist, as will be seen later, primarily in part four of this book.

The creation of an idea is a strange process that I myself do not fully

understand, even when it occurs in my own mind. Furthermore, I did not find

satisfying explanations for the phenomenon of intellectual creativity. I am not

referring here to a single concept, like those written by a copywriter, but rather

to the creation of a complex world of content such as a new paradigm. A paradigm contains a system of criteria that permits an examination in the field that

either supports or rejects accepted opinions such as, for example, the one

claiming that Israel is not a militaristic society. This process includes the

precise identification of the types of militarism that do and do not exist in Israel

through a quite innovative assumption that militarism does not have a singular

and uniform social pattern. Rather, it changes its form in different places and

from one period to another and throughout its various forms, it is possible

to see a common trait—the over-reliance on the use of force in an attempt to

solve social and political problems. Among the public at large and even among

many researchers, there is a tendency to relate to only one of the many forms

of militarism—the Praetorian type, in which the army comes out of its barracks

and the military officers seize power. The fact that this obviously did not occur

in Israel is convenient for those denying the existence of Israeli militarism.

However, all those researchers and thinkers who are, presumably, concerned

about Israel’s “good name” as a democratic state usually highlight, with praise,

the involvement of the military and the defense establishment in general in

almost all aspects of life in Israel—culture, education, economics and, of course,

politics. “The whole nation is an army,” is frequently stated with pride. A

Introduction 3

researcher and close friend of mine once claimed that the fact that most Jewish

men in the prime of their active life serve first in the army and then spend at

least one month a year in the reserves “civilianizes” the army by making it

transparent, accessible, and free of myths to most civilians. When I tried to

turn the argument upside-down by asking whether it would not be more

reasonable to assume that the extended period of time that the Israeli man (and

also, to a lesser extent, the Israeli woman) spends in the rigid military framework

may burn into his consciousness the values of army and power, or what the

professional literature calls the “military mind,” I did not receive either a theoretical or an empirical answer to my question. Therefore, I identified two interconnected types of militarism that are found in Israel: cultural militarism,

which turns the army and its symbols into a central component of the national

culture and identity; and cognitive militarism, which causes people to think in

militaristic and aggressive terms without even being aware of it. The problem

is not that the army is militaristic, since this is the nature and essence of an

army, but rather that the bulk of civilian society is also militaristic.

It is not, however, the intention of this introduction to deal with Israeli

militarism but rather to use it as an example of the development and metamorphosis of an idea and a genuine sociological issue that I researched and promoted. This idea gradually developed and matured within me over almost seven

years, during which time I criticized and dismantled the dominant thought on

the subject through discussions and debates with friends and colleagues and

sometimes, while lecturing at the university, through arguments and dialogues

with students. I am indebted to my students for several stages in the development of various ideas. In this case, for example, I owe a debt to the female

student who said in one of the lessons “We think army” and another student

who stated that “Even when we make peace, we do it using power.”

The more an idea is accepted, the more ungrateful it becomes. After a while,

it enters the public domain and severs itself from you altogether as if you were

not its “father-begetter.” I often hear many of my ideas flying around the public

sphere in the country (and some even in the world at large)—such as, for

example, Israel as a frontier society or as a state with multiple socio-political

borders, or the confrontation between the two collective identities “The Land

of Israel” vs. “The State of Israel”—without any attribution or disguised by

another concept. On the one hand, I rejoice when this happens because there

can be no greater triumph for a creator of ideas than the acceptance of his idea

as self-evident. On the other hand, the terrible little demon inside me squeals

and screams, “…but this is my child, mine, mine…” This does not mean that all

my ideas were good, and even when I suspect that they weren’t too bad, that

doesn’t mean that they were accepted. The consolidation of ideas is an ongoing

process of trial and error: primarily error.

Throughout my public writing, I almost never dealt with social topics such

as welfare, but I devoted quite a lot of space to the harm inflicted on the

universities and higher education and from this perspective, I consider myself

an elitist. I barely dealt with subjects regarding social inequalities (except,

4 Marginal at the Center

marginally, in my Hebrew book The End of Ashkenazi Hegemony) not because I

didn’t consider them important, but rather because I suppose that some

“division of labor” must exist in the sphere of public debate and struggle. Apart

from that, I also reasoned that those issues are interdependent and that changes

in the regime of occupation are a necessary precondition for the radical

treatment of problems such as poverty, education (which often functions to

reinforce existing social barriers, especially in the geographical periphery of the

country), the environment, and more.

I believe that it is proper for all human beings to have an absolute equality

of opportunity and self-actualization, and that the state must assist the weak in

the society. These core values lead me to believe that the state is obliged to act

less as a symbol and a realization of the national identity and more as a welfare

state that redistributes the common resources. Nevertheless, I do not classify

myself as a member of the left wing. My personal political identity is that of a

radical humanist. I do, however, find myself in most matters to be close to the

left although I am critical of its ideological stagnation.

This book is a combination of my life story and, briefly, that of family

members from previous generations whom I consider part of my story, together

with the most important expressions of my works both as an academic and a

public sociologist. I was able to mention only a few of the hundreds of articles

that I published in Hebrew and English and the arguments I made; otherwise

I would never have been able to complete this manuscript and no publisher

would have published it. The story does not necessarily unfold in chronological

order, and the connection between the autobiographical sections and the other

content is primarily associative. This structure may make it more difficult for

the reader, but this pattern of thinking is typical of me and is part of me.

Is there any connection between various events in my life and my public

stances? I don’t know and, in truth, this does not concern me.

Jerusalem, February 21, 2007

No comments:

Post a Comment