https://archive.org/details/isbn_9781447235514

Kindle $12.99

Available instantly

Hardcover $157.37

Paperback $38.97

Adam Hochschild

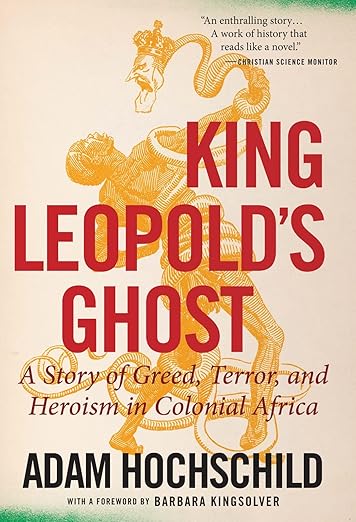

King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa Paperback – 3 March 2020

by Adam Hochschild (Author)

4.6 4.6 out of 5 stars 4,702 ratings

What are popular highlights?

Previous page

Nonetheless, the fact that trading in human beings existed in any form turned out to be catastrophic for Africa, for when Europeans showed up, ready to buy endless shiploads of slaves, they found African chiefs willing to sell.

Highlighted by 1,612 Kindle readers

In any system of terror, the functionaries must first of all see the victims as less than human, and Victorian ideas about race provided such a foundation.

Highlighted by 1,577 Kindle readers

The man whose future empire would be intertwined with the twentieth-century multinational corporation began by studying the records of the conquistadors.

Highlighted by 1,250 Kindle readers

And so the boy who had entered the St. Asaph Union Workhouse as John Rowlands became the man who would soon be known worldwide as Henry Morton Stanley.

Highlighted by 1,195 Kindle readers

The worst of the bloodshed in the Congo took place between 1890 and 1910, but its origins lie much earlier, when Europeans and Africans first encountered each other there.

Highlighted by 954 Kindle readers

Next page

Product description

Review

"An enthralling story, full of fascinating characters, intense drama, high adventure, deceitful manipulations, courageous truth-telling, and splendid moral fervor . . . A work of history that reads like a novel." --Christian Science Monitor "As Hochschild's brilliant book demonstrates, the great Congo scandal prefigured our own times . . . This book must be read and reread." --Neal Ascherson, Los Angeles Times "A vivid, novelistic narrative that makes the reader acutely aware of the magnitude of the horror perpetrated by King Leopold and his minions." --The New York Times "King Leopold's Ghost is a remarkable achievement, hugely satisfying on many levels. It overwhelmed me in the way Heart of Darkness did when I first read it--and for precisely the same reasons: as a revelation of the horror that had been hidden in the Congo." --Paul Theroux "Carefully researched and vigorously told, King Leopold's Ghost does what good history always does--expands the memory of the human race." --The Houston Chronicle --

About the Author

ADAM HOCHSCHILD is the author of eleven books. King Leopold's Ghost was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, as was To End All Wars. His Bury the Chains was a finalist for the National Book Award and won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize and PEN USA Literary Award. He lives in Berkeley, California.

Top reviews

Top reviews from Australia

M Tanzil

5.0 out of 5 stars Not just a book, it's historyReviewed in Australia on 19 January 2022

Verified Purchase

This is one of the my most favorite book. If you love history and want to know part of African history/ congo, this is highly recommended. Writer brought history back to life , it's complex history but simply written.

HelpfulReport

John Johnson

5.0 out of 5 stars Really Good History of the AreaReviewed in Australia on 7 July 2021

Verified Purchase

I wasn't familiar with the history around what happened and the sheer tragedy of it all. The level of brutality was astounding. But very well written and readable.

HelpfulReport

Alex

4.0 out of 5 stars Obscured pastReviewed in Australia on 29 March 2021

Verified Purchase

Interesting account of the various organisations which took up the fight of stopping the horror in the Congo. Not a page-turner but well researched and written historical eye-opener.

HelpfulReport

Alex

5.0 out of 5 stars it reads really well and keeps you interested in the many aspects of this horrible period of historyReviewed in Australia on 5 November 2015

Verified Purchase

Wow...an unbelievable and entirely unexpected story that grips you from the first chapter. Although it is essentially a historical account of the Belgian occupation of the Congo, it reads really well and keeps you interested in the many aspects of this horrible period of history. Once he gets into the detail of how brutal the occupation was I found it difficult to read further, but felt that the story was so compelling that I couldn't stop.

Definitely a worth a read if you would like to understand a little more of why this part of the world is in the state of anarchy it is today

One person found this helpful

HelpfulReport

Sdheda

5.0 out of 5 stars History always repeats itselfReviewed in Australia on 8 June 2018

Verified Purchase

A well written easy to read depiction of the Congo history. We must never forget and pray it never happens again

HelpfulReport

Paul Cartwright

5.0 out of 5 stars Just shows how terrible King Leopold II really wasReviewed in Australia on 5 January 2018

Verified Purchase

Just shows how terrible King Leopold II really was!

Will be a reference book to the Congo's history for years.

HelpfulReport

Jimbob

5.0 out of 5 stars Worth the read!Reviewed in Australia on 20 June 2017

Verified Purchase

Nicely written and well thought out account of a horrible time in history.

HelpfulReport

sally tarbox

5.0 out of 5 stars "A fine chance to secure for ourselves a slice of this magnificent African cake"Reviewed in Australia on 3 April 2017

A masterly work looking at the hideous colonial rule of the Congo by the Belgians. King Leopold II was a dissatisfied monarch of a small land, casting about for colonies to give him money and prestige. Alerted to the vast area and possibilities of the Congo Basin by recent explorations by Henry Moreton Stanley, Leopold made it his mission to acquire the region.

This was not (originally) a Belgian possession but "a secretive royal fief". Leopold was a master propagandist, calming the fears of other European powers by focussing on his philanthropic motives for entering the Congo. In reality, his interests lay in the ivory, the rubber and the potential for slave labour. Reports on the actual awful goings-on - the murders, floggings, mutilations and people worked to death - were largely quashed by Leopold's charm, his bribes and his seeming kindly nature.

A few heroes made a stand against him however, notably ED Morel and Roger Casement (who I'd only heard of as an Irish 'traitor' before - he was actually a fine and principled individual on this matter.)

Very readable book on a topic that has been conveniently forgotten.

HelpfulReport

See more reviews

Top reviews from other countries

Translate all reviews to English

Amazon Customer

5.0 out of 5 stars PainfulReviewed in the United States on 8 June 2024

Verified Purchase

In May, we had the opportunity to be in Antwerp Belgium. In Antwerp, there is a statue of a man that cut off the hand of a giant. That giant was preventing the city of Antwerp from being all that it could be.

When I saw that statue, I was appalled. I remembered what happened to the people of the Congo, and that statue reminded me of where Leopold and his men got the idea to cut off the hands of people. This book was a painful read. I could only read it in sections. It’s an unfortunate segment of history. But I think it is important that we remember. The author did an amazing job.

Report

Cesar Volpe

5.0 out of 5 stars Extraordinário.Reviewed in Brazil on 24 March 2024

Verified Purchase

Poucas vezes se encontra um trabalho documental tão profundo, sobre um momento histórico tão decisivo, de forma tão literária — história com gosto de romance, mistura perfeita de entretenimento e informação.

Report

Translate review to English

Kindle Customer

5.0 out of 5 stars A brilliant bookReviewed in the United Kingdom on 3 November 2023

Verified Purchase

Very well written and exceedingly readable. Clearly tremendously well researched. Fascinating, eye-opening and should be read by everyone interested in Africa - and the absolutely vile nature of Man. The last few pages, briefly mentioning what was going on in the rest of the world are probably (for me at least) more shocking than the whole Congo aspect.

Prompted by this book I have now bought Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’ and Raoul Peck’s ‘Lumumba’…! And I know I will be contemplating this book for a LONG time to come!

2 people found this helpfulReport

RobNraz

5.0 out of 5 stars Mycket bra bokReviewed in Sweden on 9 October 2023

Verified Purchase

Mycket bra och hemsk bok. Helt klart läsvärd om du intresserar dig för historia

Report

Translate review to English

Marcus Bennemann

5.0 out of 5 stars Fast delivery and good product.Reviewed in Germany on 24 December 2022

Verified Purchase

Book was like new.

Report

See more reviews

=====

BOOK REVIEWS

cover

Order this book from Amazon.com

King Leopold's Ghost, by Adam Hochschild

Houghton Mifflin, 1999

Reviewed by Eric Garcetti Co-Chair Young Advocates, California Committee South

In a passage at the beginning of Conrad's Heart of Darkness, Marlow looks out from his ship near the sea-reach of the Thames and says:

"I was thinking of very old times, when the Romans first came here, nineteen hundred years ago. . . think of a decent young citizen in a toga. . . coming out here in the train of some prefect, or tax-gatherer, or trader, even, to mend his fortunes. Land in a swamp, march through the woods, and in some inland post feel the savagery, the utter savagery, had closed round him, -- all that mysterious life of the wilderness that stirs in the forest, in the jungles, in the hearts of wild men."

Conrad, who wrote the Heart of Darkness after a chilling trip up the Congo River in 1890, recognized how yesterday's savages were tomorrow's paragons of civilization. He eloquently pointed out that European colonialists of the late 19th century were no more "civilized" than the "savages" they sought to rule in sub-Saharan Africa at the turn of the last century.

Writing a century later, Adam Hochschild revisits Conrad's Congo to tell the tale of Belgian king Leopold II's colonial savagery and his creation of a personal colony in the heart of Africa.

During the last two decades of the 19th century, under the pretense of a humanitarian mission to save Africans from slavery and alcohol, Leopold seized an immense swath of land (an area seventy-six times the size of Belgium) around the Congo River. Seeking political prominence and economic gain, Leopold had tried to purchase land in Latin America and Asia from several European powers. Unsuccessful, he turned to unclaimed parts of sub-Saharan Africa and employed Henry Stanley (of "Dr. Livingstone, I presume" fame) as his personal agent.

In 1890, when John Dunlop's invention of the inflatable bicycle tire launched a worldwide rubber boom, Leopold found himself ruling one of the greatest stretches of wild rubber in the world. He immediately began to cash in, implementing a brutal system of forced labor to bring harvested rubber to Europe. Troops would enter a village, round up women and children and hold them hostage until the men brought back a quota of rubber. Torture, rape, murder, and widespread death from rubber harvesting halved the Congo's population within two decades while bringing Leopold a fortune of more than $1 billion (in today's terms).

Hochschild's purpose is not just to chronicle the brutality of Belgian colonialism, but also to tell the story of the courage of individuals who tried to uncover the scale of human suffering in the Congo. Edmund Morel, a clerk for the London shipping company that had a monopoly on transport to and from the Congo, was first to notice that the ships bringing ivory and rubber from the Congo returned loaded with weapons and soldiers. Leopold claimed that he was opening the Congo to free trade, but Morel realized that the weapons and soldiers meant the rubber was being harvested under conditions of near-slavery. Having no background in political activism, risking his family's security and giving up his own job, Morel devoted most of his adult life to uncovering and publicizing the savagery of the rubber trade in the Congo.

Morel is joined by a rich cast of human rights activists, among them William Sheppard and Roger Casement. Sheppard, an African-American Presbyterian missionary, escaped the discrimination of the Jim Crow south and was embraced by the powerful Kuba kingdom, to become one of the first non-Africans to travel to the Kuba capital. Casement, a British consul, became one of Morel's closest allies and collaborators. Hochschild also includes the voices of many Congolese who struggled to resist Leopold's voracious quest for rubber.

The book reads like a novel -- rich in anecdote and benefiting from Hochschild's sharp eye for detail. We learn that the "great" explorer Stanley was in fact an insecure, cruel, lying self-invented man who once cut off his own dog's tail, cooked it, and fed it to the dog when he was upset with it. We learn of the baroque perversities of Leopold's own family. Perhaps most troubling is to realize that without Leopold, someone else would have been there to implement a brutal and horrifying a system of colonial labor (indeed, the neighboring French Congo saw similar suffering during colonial rule). And yet, the courage, perseverance, and determination of individuals like Morel, Sheppard, and Casement revealed injustices that allowed the world, if only for a moment, to see who the true savages were.

BACK TO COMMUNITY: BOOK REVIEWS

===

Displaying 1 - 10 of 3,961 reviews

Profile Image for William2.

William2

789 reviews

3,412 followers

Follow

January 28, 2023

A few things. First, I have read widely about Mao's Cultural Revolution and Great Leap Forward (40 to 70 million dead), Stalin's purges and programs of collectivization (20 million dead) and Hitler's genocide (11 million dead). I am largely unshockable. However, the avarice and deceit of King Leopold II of Belgium in the Congo (15 million dead) has been something of a revelation. I hereby enter his name in my Rogues Gallery roster. It is important that we remember what he perpetrated for his own personal gain. Adam Hochschild's book does an excellent job of registering these crimes in the collective memory. The book has been justly praised. Let me add my own.

Also, it turns out the first great unmasker of Leopold was an American, George Washington Williams. He was a lawyer, minister, popular author and activist. He wrote an open letter to Leopold that was published in the Times in 1890 and which might have saved millions of lives had he been listened to. Williams was a man of considerable intellectual acumen and courage. Largely because he was black, however, he was ignored. I had always thought that that great whistleblower was Roger Casement. And certainly Casement's key contribution is recounted here, as is that of the great popularizer of the Congo cause, E.D. Morel, but Williams' audacious early warning was a surprise to me. I hereby enter his name into my book of latter-day Cassandras, and decree he be given greater emphasis in all relevant texts and courses.

20-ce

africa

belgium

...more

512 likes

6 comments

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Jeffrey Keeten.

Jeffrey Keeten

Author

6 books

250k followers

Follow

May 17, 2019

”The Congo in Leopold’s mind was not the one of starving porters, raped hostages, emaciated rubber slaves, and severed hands. It was the empire of his dreams, with gigantic trees, exotic animals, and inhabitants grateful for his wise rule. Instead of going there, Leopold brought the Congo—that Congo, the theatrical production of his imagination—to himself.”

photo King20Leopold20II_zpsx1f6dans.jpg

King Leopold II

Belgium was simply not big enough for the future king. ”When he thought about the throne that would be his, he was openly exasperated. ‘Petit pays, petits gens’ (small country, small people), he once said of Belgium.” He watched as countries like Holland, Great Britain, France, Portugal, Spain, Italy and Germany were colonizing Africa and other exotic isles and becoming rich off the plunder. In the 1880s, he saw his chance and claimed the lands of the Congo. He did this without any kind of referandum from his people. He knew what was best for Belgium. ”Most Belgians had paid little attention to their king’s flurry of African diplomacy, but once it was over they began to realize, with surprise, that his new colony was bigger than England, France, Germany, Spain, and Italy combined. It was one thirteenth of the African continent, more than seventy-six times the size of Belgium itself.”

They had no idea the level of atrocities that would be perpetrated in the name of Belgium.

I’ve always thought of Leopold II as a 2nd tier genocidal maniac. I’d always reserved the 1st tier for Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin, but after reading this book and hearing the estimated number 10 million associated with the deaths in the Congo, I have officially moved Leopold II to the 1st tier genocidal maniac. So why don’t we know more about Leopold II? Why don’t we see him as the genocidal maniac that we associate with the names Hitler and Stalin?

Could it be because he was killing black people?

Another factor is the way Leopold worked tirelessly to convince people he was a great humanitarian. He found people who would help support him in this endeavor and paid them to write reports that were favorable to his reputation in Africa. He worked equally tirelessly to squash those who came back from the Congo with the lists of atrocities they had witnessed while in Africa.

The biggest thorn in Leopold’s voluminous backside turned out to be a British shipping clerk named Edmund Morel, who noticed the amount of goods coming from the Congo that were being traded or sold at prices that would not support a living wage in the Congo. The math did not add up. The only way that Leopold could be selling goods this cheaply was if they were being acquired through slave labor. Morel went on to found a paper that continued to expose Leopold’s criminal activities in the Congo. Morel hammered away at him for the rest of his life. Additionally, Roger Casement was an Irish man who risked life and limb to obtain evidence that directly refuted the rosy picture that Leopold was selling Europe. There were also two American black men, George Washington Williams and William Sheppard, who did everything they could to expose Leopold’s monstrosities to the world. There were many other people who tried their best to stop what was happening, unchecked, in the Congo.

The problem was that Europe and the United States wanted to believe Leopold.

The most famous book of celebrated author Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness was set in the real Leopold’s Congo. The famous character of Kurtz was based on a man Conrad met in the Congo.

photo Leon Rom_zpsnahgnrhh.jpg

Should I chase butterflies today or should I lob off a few heads?

”One prototype for Conrad’s Mr. Kurtz: Léon Rom. This swashbuckling officer was known for displaying a row of severed African heads around his garden. He also wrote a book on African customs, painted portraits and landscapes, and collected butterflies.”

Léon Rom was a civilized, well educated man. So how does decorating your garden with severed African heads equate with butterfly collecting and painting portraits and landscapes?

Leopold flooded the Congo with the right sort of men. Mercenaries capable of chopping off hands, raping uncooperating women, murdering men, women, and children, and lashing men who didn’t bring enough rubber back from the jungle with ”the chicotte—a whip of raw, sun-dried hippopotamus hide, cut into a long sharp-edged corkscrew strip.”

The strip this would cut off a man’s back, buttock, and legs would leave deep, permanent scars if the man was lucky, or in many cases unlucky, enough to live. *shudder*

White men felt free of all law in the Congo. “We have liberty, independence, and life with wide horizons. Here you are free and not a mere slave of society. . . . Here one is everything!” So to live as free as one would like, one must enslave others? These men had harems, money, and status, something they could never achieve working as clerks or plumbers in Europe. In the Congo, they were warlords.

They killed so many Congolese that they feared not having enough slaves to maintain the plundering of the Congo. “‘We run the risk of someday seeing our native population collapse and disappear,’ fretfully declared the permanent committee of the National Colonial Congress of Belgium that year. ‘So that we will find ourselves confronted with a kind of desert.’” It reminds me of hunters who hunted species to extinction and then bemoaned the fact that they couldn’t hunt those animals anymore. At no point did they think to themselves, maybe we are killing these animals faster than they can reproduce.

photo Congo20missing20hands_zps7ihstkux.jpg

So why cut off the hands? It seems counterproductive when you need these men to work. Every bullet had to be accounted for with Leopold’s mercenaries, so if a man used a bullet to kill game, he had to have an African hand to account for that bullet. Every African hand was then turned in for a reward. It is too sick to comprehend.

Every country in Africa has tales of horror and outrage at the hands of European colonizers. I do believe that what happened in the Congo was by far the worst atrocities on a native population in Africa. The sad part of it is that most of us don’t know anything about it. I knew some, but I didn’t know enough. The “cake” that was Africa was cut up into portions and served to the white European countries as casually as if they were discussing the fates of Africans at a garden party with their children playing at their feet and their wives bringing them slices of the Congo, Nigeria, Kenya, Algeria, South Africa, and Senegal with which they could gorge themselves.

Adam Hochschild had a difficult time getting this book published. It was as if the ghost of Leopold was still haunting and suppressing the truth. This is a brilliant and important book that exposes the truth of the Congo and the complicity which every “civilized” country played in allowing such atrocities to occur.

If you wish to see more of my most recent book and movie reviews, visit http://www.jeffreykeeten.com

I also have a Facebook blogger page at:https://www.facebook.com/JeffreyKeeten

Show more

africa

exploration

greed

...more

354 likes

5 comments

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Trevor.

Trevor

1,346 reviews

22.9k followers

Follow

March 20, 2018

This is a remarkably painful book. There are a number of estimates given throughout of the extent of the extermination of people in the Congo under King Leopold – the author says perhaps 8-10 million people, but he also quotes someone who believes it might have been as many as 13 million people. This does not include, obviously enough, the children who were not born because their parents could not face bringing them into such a world. I mention this because at one point the author quotes people who say exactly that and goes on to say that one of the things people noticed at the time was the all too obvious gap in the population of the unborn. The hellish extent of the nightmare inflicted on these people by Western greed simply beggar’s belief. Kidnapping family members to force other members of their family to work for you to pay off your ransom, mutilating and whipping them when they do not reach the quotas and production targets you have set, killing people horribly for the most minor infractions – this is the horror story white people have repeated time and time again upon people in the developing world. This is the origin of Conrad’s ‘Heart of Darkness’. And that dark heart continues to beat in our chests.

What makes this story particularly disgusting is that King Leopold of Belgium was, for far too long, praised as a philanthropist and anti-slave crusader while he was turning a nation into a killing field. That is, while he was conducting one of history’s worst acts of slaughter – one where there were perhaps twice as many victims as in the holocaust – he was fated as a great and humane leader. Having just read ‘Small Change’ by Michael Edwards, it is all too easy to can see where our modern day philanthropists learnt their trade.

There are heroes in this book too – none greater than the nameless Africans who fought and died unrecorded and unremembered – something the author as one of the cruel silences here. This is part of the reason I’m drawn to Critical Race Theory – written in recognition of the fact that the oppressed are too often without a voice, and so finding ways of presenting sociological research that privileges their stories and gives them voice is an act of justice and humanity. The work of W.E.B. Du Bois, and in particular his masterful ‘The Souls of Black Folk’, provides a tour-de-force of what can be achieved by such presentations of sociological research.

But of the named heroes here, and I’m not saying this because I was born in Ireland, the one I found most compelling was Roger Casement. As a homosexual who lived his life in fear of being outed, as a visionary who believed the riches of the Congo should have gone to the Congolese, as a protestor against imperialist wars, it is hard to think of someone braver, more visionary or further ahead of his time.

“It is dark, dark,

With the swarmy feeling of African hands

Minute and shrunk for export,

Black on black, angrily clambering.”

Silvia Plath – The Arrival of the Bee Box

As always in life, it is the appallingly simple images that stay with you long after reading a book like this – and in this book the inescapable image is also a rather bizarre one – that of severed African hands that have been smoked, and also their nightmarish metaphorical doubles, made of Belgium chocolate and still sold without shame today. The hands were cut off and smoked to be given to the administrators to prove the bullets used to kill their victims had not being wasted (they mention later that the administrators were concerned that female hands were being used and so dried penises were later used as proof of kill). You can Google ‘Belgium chocolate hands’ if you have a stomach to.

A couple of years ago London’s financial district offered an apology for the role it had played in the Slave Trade. It is all very nice to apologise – but there are a couple of things that make such apologies sound somewhat hollow. The first is that London continues to benefit from the money made from that trade – even today, and the benefits of those dead and tortured Africans are still tangible in glories and wealth of Europe. And yet, the apology certainly did not extend to any question of the payment of reparations for the crimes of our past that we continue to benefit from.

The other uncomfortable fact is that we continue our rape of Africa and African resources even today while, just as our forefathers did whose actions we apologised for, we continue to leave those who ought to benefit from those resources destitute and worse.

I will now need to read more about the US government’s murder of Patrice Lumumba – something else that, as with so many US interventions in foreign countries, provide yet another crime against humanity to be stacked against the litany of others. You know, when you invariably chose the side of the oppressor over the liberator, maybe it says something about your own preferences…

This book should be compulsory reading. Not least because horror did not end a hundred years ago, it is all still happened now.

Show more

history

race

183 likes

2 comments

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Beata.

Beata

806 reviews

1,261 followers

Follow

April 15, 2019

The book was written 20 years ago, and yet, it is so eye-opening! The theme has not been covered enough …. My idea of atrocities committed in the Congo in the second half of the 19th century were more than basic and narrowed to Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, which I read (and now should re-read) but didn’t take too much interest in Conrad’s time in the Congo, which was a mistake … Author who undertakes a most difficult task to write about crimes against humanities (term used for the first time by one of the 19th century journalist with regard to the Congo) pays respect to all the victims of one’s madness, greed, cruelty, indifference or hatred. And I read this book, or rather listened to it, with precise the same intention. There are several characters central to the unravelling the crimes that must be mentioned: William Sheppard, George Williams, E.D. Morel and Roger Casement. They were the first to report openly on the cruelty towards the indigenous tribes and campaign against it. Ordinary people and yet extraordinary in those days to speak and write openly of what they witnessed. I can do nothing more than pay respect to the millions of victims who happened to live in the area rich in resources exploited to the full by white men. This book is both overwhelming and depressing, however, it is one that should be read along with all the others that cover any crime against human beings.

PS Writing these few sentences was not easy for me as I found this book too upsetting and painful to comment on ....

Thank you to my GR Friends who drew my attention to this book.

favorites

183 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Orsodimondo [part time reader at the moment].

Orsodimondo [part time reader at the moment]

2,294 reviews

2,166 followers

Follow

July 30, 2022

CRIMINI CONTRO L’UMANITÀ

Cuore di tenebra è spesso considerato un’allegoria, o una parabola, freudiana – e Kurtz, il suo protagonista assassino, un folle che ha letto troppo e digerito male Nietzsche.

In realtà, come il libro di Hochschild dimostra, Kurtz fu basato su un collage di figure storiche e l’orrore descritto era realistico quanto mai: il romanzo di Conrad è un ritratto preciso dettagliato e profondo di quello che era il Congo sotto la dominazione del re del Belgio, Leopoldo II, negli anni a cavallo della fine del secolo XIX (1885-1908), quando fu perpetrato uno dei genocidi di cui si è parlato meno e dimenticato di più (la storia si è poi ripetuta: la Grande Guerra Africana a cavallo dell’inizio del terzo millennio, con i suoi 5 milioni di morti e passa nel solo Congo, chi ne parla, chi se la ricorda, che segno ha lasciato?...)

Sotto il regno del terrore instaurato dai militari funzionari agenti impiegati missionari inviati da Leopoldo II (che non mise mai piede nella colonia così fortemente voluta e difesa), la popolazione del Congo si ridusse della metà, con la morte di circa dieci milioni di africani.

Il saggio dell’americano Hochschild, studioso e docente di storia dei diritti umani, pur se essenzialmente basato sulla monumentale ricerca storica di Jules Marchal, e su uno studio di Thomas Pakenham, diventa quasi un romanzo grazie al talento divulgativo di Hochschild che sa infarcire i fatti con episodi di diplomazia, biografie dei protagonisti, matrimoni, letteratura cronaca e resoconti giornalistici dell’epoca, diari ed epistolari, statistiche, interviste e qualsiasi testimonianza diretta.

Chiaramente le voci che mancano sono quelle delle vittime, lo stesso Hochschild è il primo a sottolinearlo e a lamentarlo: questo libro mi sembra dedicato proprio a loro.

È attento alla storia delle invenzioni, come quella del fucile a retrocarica e della mitragliatrice e degli pneumatici gonfiabili – ma anche all’artigianato, per spiegare il grande uso che si faceva all’epoca dell’avorio e della gomma.

Il colonialismo, dipinto per quello che è veramente stato (conquista, sopruso, rapina, devastazione, violenza, sopraffazione, sadismo, crudeltà, ingiustizia, tortura…), genera anche la nascita dei primi movimenti in difesa dei diritti umani: le origini di Amnesty International e altre organizzazioni umanitarie contemporanee possono essere rintracciate nei fatti e nel periodo storico che Hochschild ci racconta.

I cesti che servivano per la raccolta. La gomma è morte per la popolazione locale, ricchezza per i bianchi colonizzatori.

Un minuscolo stato come il Belgio si trovò a governare e controllare un impero coloniale 77 volte più grande.

E, come se non fossero bastati i massacri perpetrati in Congo, durante la Prima Guerra Mondiale, i belgi andarono a colonizzare anche più a est, in Rwanda e Burundi, dove riuscirono a comportarsi peggio dei tedeschi che li avevano preceduti: in queste terre i missionari belgi riuscirono a offrire il peggio.

Re Leopoldo II (Leggere la corrispondenza del re Leopoldo II è come leggere le lettere dell’amministratore delegato di una società che ha appena messo a punto un nuovo prodotto redditizio e si affretta ad approfittarne prima che i concorrenti possano mettere in funzione le proprie catene di montaggio.) riuscì a far credere all’Europa e agli Stati Uniti che la sua missione era prima di tutto umanitaria, liberare l’Africa dalla piaga dello schiavismo condotto dai mercanti “arabi”: chissà poi perché diede alle fiamme il suo archivio con scrupolo sistematico come neppure Hitler o Stalin si premurarono di fare…

Incontrare Kurtz.

…Williams utilizzò un’espressione che sembra tratta dai verbali dei processi di Norimberga di oltre cinquant’anni dopo. Il Congo di Leopoldo, scriveva, era colpevole di “crimini contro l’umanità”

I bianchi che attraversarono il territorio del Congo in veste di ufficiali militari, capitani di battello e funzionari di società statali o concessionarie accettarono l’impiego della chicotte con la stessa indifferenza con cui, cinquant’anni più tardi, centinaia di migliaia di altri uomini in uniforme avrebbero accettato i loro incarichi nei campi di concentramento nazisti e sovietici.

Come sarebbe successo decine di anni dopo nei gulag sovietici, un altro sistema schiavista per la raccolta di materie prime, il Congo applicò la politica delle quote. In Siberia, le quote erano relative ai metri cubi di legno tagliato o alle tonnellate d’oro estratte ogni giorno dai prigionieri; in Congo ai chili di gomma.

Cento anni fa, all’epoca della controversia sul Congo, l’idea dei pieni diritti umani, politici, sociali ed economici, era una minaccia per l’ordine costituito di molti paesi del mondo. Lo è ancora oggi.

Gli utili si accumulavano con rapidità perché, costi di trasporto a parte, la raccolta della gomma selvatica non richiedeva coltivazioni, fertilizzanti né investimenti di capitali in apparecchiature dispendiose. Richiedeva solo manodopera.

Questa foto è tra quelle pubblicate nel libro, ed è forse quella che mi ha colpito di più: sembra sospesa, sembra innocente... In realtà, si tratta di un padre che guarda la mano e il piede mozzati alla figlia. Era pratica diffusa mozzare mani e piedi per punizione: i moncherini compaiono in molte foto, e i 'trofei' sono spessi raccolti ed esposti dentro ampi cesti.

africa-congo

americana

genocidio-e-dintorni

146 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Beverly.

Beverly

892 reviews

352 followers

Follow

June 28, 2019

The best non-fiction book I've ever read. The hyphenated title on the book is a story of greed, terror and heroism in colonial Africa and that sums it up very well. Such horrific treatment including brutal maiming and killing of workers, including children, who refused to work for King Leopold's rubber plantations is a story untold for centuries and deserves this fine treatment by Adam Hochschild. King Leopold of Belgium was an unrepentant monster.

favorites

88 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Warwick.

Warwick

882 reviews

14.9k followers

Follow

July 23, 2016

‘Exterminate all the brutes!’ – Kurtz

A very readable summary of one of the first real international human rights campaigns, a campaign focussed on that vast slab of central Africa once owned, not by Belgium, but personally by the Belgian King. The Congo Free State was a handy microcosm of colonialism in its most extreme and polarised form: political control subsumed into corporate control, natural resources removed wholesale, local peoples dispossessed of their lands, their freedom, their lives. To ensure the speediest monetisation of the region's ivory and rubber, about half its population – some ten million people – was worked to death or otherwise killed. And things were no picnic for the other half.

Hochschild's readability, though, rests on a novelistic tendency to cast characters squarely as heroes or villains. Even physical descriptions and reported speech are heavily editorialised: Henry Morton Stanley ‘snorts’ or ‘explodes’, Leopold II ‘schemes’, while of photographs of the virtuous campaigner ED Morel, we are told that his ‘dark eyes blazed with indignation’. This stuff weakens rather than strengthens the arguments and I could have done without it. Similarly, frequent references to Stalin or the Holocaust leave a reader with the vague idea that Leopold was some kind of genocidal ogre; in fact, his interest was in profits, not genocide, and his attitude to the Congolese was not one of extermination but ‘merely’ one of complete unconcern.

Perhaps most unfortunate of all, the reliance on written records naturally foregrounds the colonial administrators and Western campaigners, and correspondingly – as Hochschild recognises in his afterword – ‘seems to diminish the centrality of the Congolese themselves’. This is not a problem one finds with David van Reybrouck's Congo: The Epic History of a People, where the treatment of the Free State is shorter but feels more balanced. (Van Reybrouck, incidentally, regards Hochschild's account as ‘very black and white’ and refers ambiguously to its ‘talent for generating dismay’.)

For all these problems, though, this is a book that succeeds brilliantly in its objective, which was to raise awareness of a period that was not being much discussed. It remains one of the few popular history books to have genuinely brought something out of the obscurity of academic journals and into widespread popular awareness, and it's often eye-opening in the details it uncovers about one of the most appalling chapters in colonial history. The success is deserved – it's a very emotional and necessary corrective to what Hochschild identifies as the ‘deliberate forgetting’ which so many colonial powers have, consciously or otherwise, taken part in.

belgium

colonialism

dr-congo

...more

89 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Michael.

Michael

1,094 reviews

1,830 followers

Follow

September 4, 2013

This work of popular history does a great job of bringing to life the story of King Leopold of Belgium’s orchestration of a private empire in the Congo near the end of the 19th century. His greed driven campaign presaged the 20th century shenanigans with its use of political intrigue, bribery, media manipulation, and lies. The popular explorer Henry Morton Stanley was wooed and appropriated to make his dream become a reality. Its economic success was founded on the institutionalization of slave labor, terrorism, and intimidation of both the population and participants long before Stalin and Hitler adopted such methods. In one way the tale represents a special case of evil genius; in another way it is a case study of approaches broadly common to European colonialism in Africa. When the atrocities behind Leopold’s money machine for ivory and rubber were first recognized, they sparked a brilliant protest movement led by two notable Englishmen. Hochschild makes their story is as interesting as that of Leopold and Stanley’s.

Belgium was late to the feeding frenzy of carving up Africa, and Leopold developed a gnawing hunger for a piece of the pie. Stanley’s forays through central Africa brought Leopold’s attention to the vast area of the Congo River basin, an area the size of India or much of Europe. As an example of Hochschild’s knack of characterization, check out his profile of Stanley at the point of his first meeting of Leopold at age 37:

The ne’er-do-well naval deserter of a mere thirteen years earlier was now a best-selling author, recognized as one of the greatest of living explorers. His stern, mustachioed face appeared in magazines everywhere beneath a Stanley Cap, his own invention …which, in a way, summed up Stanley’s personality: one part titan of rugged force and mountain-moving confidence; the other a vulnerable, illegitimate son of the working class, anxiously struggling for the approval of the powerful. In photographs each part seems visible: the explorer’s eyes carry both a fierce determination and a woundedness.

Stanley’s job over a five year period was to establish a transportation system and treaties with the populace that gave Leopold carte blanche. His well-paid tasks included building a road past the 200 plus miles of falls in the coastal segment of the river, hauling a disassembled steamship to the navigable portion, and the establishment of many trading posts/military bases along its 1,000 mile main course of the Congo River. Above all he was to buy with goods like clothes and alcohol written deals with all the chiefs and village leaders along the way that handed over a trading monopoly to Leopold under the guise of his benign sounding “International Association of the Congo”. The illiterate chiefs couldn’t have known what they were signing. “The treaties must be as brief as possible,” Leopold ordered, “and in a couple of articles must grant us everything.” Their text promises that the signers would:

freely of their own accord, for themselves and their heirs and successors for ever … give up to the said Association the sovereignity and all sovereign and governing rights to all their territories …and to assist by labor or otherwise, any works, improvements or expeditions which the said Association shall cause any time to be carried out in any part of these territories …All roads and waterways running through this country, the right of collecting tolls on the same, and all game, fishing, mining, and forest rights, are to be the absolute property of the said Association.”

By labor or otherwise. Stanley’s pieces of cloth bought not just land, but manpower. It was an even worse trade than the Indians made for Manhattan.

The territory included at least 200 different ethnic groups speaking more than 400 languages and dialects, ranging from “citizens of large, organizationally sophisticated kingdoms to the Pygmies of the Ituri rain forest, who lived in small bands with no chiefs and no formal structure of government.” Through intermediary companies which Leopold held at least half the shares, the men of the tribes were forced into labor as porters, food producers, and gatherers of ivory and, later, rubber. Force was effected by making a hostage of wives, children, or chiefs as hostages and intimidation through razing of villages, chopping off of children’s hands, or public whippings of those who did not make their quotas. A lot of this dirty work was carried out be a cadre of black people controlled by their own system of carrots and sticks.

description

Although other European colonies used these practices, Leopold’s intermediaries advanced their use on an unprecedented scale. What was especially outrageous was that the takeover of the Congo was sold to world under the humanitarian guise of eradicating the slave trade and civilizing the savages with the light of Christianity. Some of this duplicity was captured by Conrad in his “Heart of Darkness”. The concept that the evil incarnate of the company agent, Kurz, was a fictional parable is dismissed by Hochschild, who comes up with several candidates for realistic models that Conrad could have met or learned of during his employment on a river steamer.

In the absence of official national military to back up his claim to the Congo, Leopold’s ability to get a consensus of powerful countries to accept his new “Congo Free State” was his next amazing accomplishment. It started with getting the U.S. Congress to recognize it as a sort of protectorate, a coup based on bribery, harnessing missionary groups, and a massive lobbying campaign. Playing Germany, France, and England against each other at a conference in Berlin was the second phase; i.e. the pretension of a free-trade region under harmless Belgian hands was better than the threat of takeover by a more powerful nation.

Early heroes of this sad tale include two black Americans. George Washington Williams, an ex-Union soldier in the Civil War, journalist, and budding historian, showed up in the Congo in 1890 to explore the potential for the region as a place for American blacks to emigrate to. His investigations led him to the first media expose of the true situation. His open letter to Leopold called a spade a spade: the trading sites were labeled “piratical, buccaneering posts” that operated chain gangs and village burnings, and the conclusion was that “your Majesty’s government is engaged in the slave trade, wholesale and retail.” He got the letter published in newspapers and a long report disseminated; it had less impact than it might have if he hadn’t died soon thereafter from TB. The contributions of the black missionary William Henry Sheppard as a brave witness to the atrocities continued into the later phase of whistle blowing.

A few years later, a Liverpool shipping administrator, E.P. Morel, developed into a more unlikely fly in the ointment for dear Leopold. In a leap of logic, he inferred from all the goods shipped on his ships out of the Congo compared to primarily weapons and ammunition sent on returning trips that the colony had to be founded on slavery. Who could have guessed that this apolitical man would feel such outrage and be driven to masterful such effective skills in marshaling information, journalistic and speaking presentation, shaping his message to his audience, and use of celebrities in fund raising. A powerful ally was enlisted in the form of a respected diplomat, Roger Casement, the first British consul to the Congo Free State. His own investigations brought a lot of documentation and recorded testimony to the advocacy efforts. The avalanche of public outcry they raised would rival that of the anti-slavery campaign of decades before and presage some of the more successful strategies of advocacy groups in present modern era. Photographs of Congolese in chains and of individuals with their hands cut off as punishment made good fuel for the fire. A book by Arthur Conan Doyle and satirical pamphlet roasting Leopold by Mark Twain are examples that amplified the impact of Morel and Casement's work.

Eventually, Leopold was forced to transfer his colony into Belgian state control. But not before a week of burning all official records of the reign of terror in Belgium and Africa. Hochschild credits Morel for the success, but he takes pains to educate the reader how the big picture of brutal exploitation of the people of the Congo did not change. He also highlights the blindness of Morel to the possibility of self-rule in the Congo and to the adverse impacts of British excesses in its own colonies. The CIA led assassination of the democratically elected president of Republic of Congo in 1961 and installment of the brutal dictator Mobutu, who ruled in Zaire for three decades, follows the same mindset of imperial entitlement among developed countries with respect to the fate of African peoples. While evidence of a population loss of half of Congo’s residents under Leopold’s commercial regime can be used to claim some level of guilt for the death of 8-10 million people, Hochschild points out that similar population losses have been estimated for colonies under French control over a similar period.

Hochschild’s highly readable history of the rape of the Congo was a great education for me how one king’s bizarre successes could represent in microcosm the more complex and lengthy process involved with other cases of colonial subjugation.

Show more

africa

belguim

colonialism

...more

87 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Malia.

Malia

Author

7 books

622 followers

Follow

August 6, 2020

This is a difficult book to review, because I am still thinking about it and probably will for some time. Of course I knew about King Leopold and his cruelty in the Congo, but nothing to this extent. The story Hochschild tells is one that left me consistently shocked, disgusted and deeply saddened and yet this is a book I would recommend to just about anyone. It strikes me again and again how cruel and vicious people can be to those they view as the "other", to those they view as someone less than themselves or even less than human based on their skin color, religious differences or any manner of means by which to conjure prejudice and hatred. We see it in the news every day, and though it feels overwhelming at the moment due to the nature of modern media, I venture to say it has always been this way, "us" pitted against "them" with the result of violence. That being said, I want to inject a note of hope here as well, just as Hochschild does in his book. There are always, too, those that recognize this injustice, who are willing to speak up and to risk their own safety and peace to fight for those who cannot. King Leopold's Ghost is a book I won't be quick to forget and it makes me all the more aware of how much I do not know about this world, and how much is not taught in schools and it is up to us to learn if we want to try to understand the world and humanity or a lack thereof. This is a bit of a ramble, but hopefully I am getting across how impactful this book is and how worth the read.

Find more reviews and bookish fun at http://www.princessandpen.com

best-of-2019

non-fiction

81 likes

Like

Comment

Profile Image for Dmitri.

Dmitri

220 reviews

190 followers

Follow

October 11, 2023

This is a tragic history of the Belgian Congo at the end of the 19th century after the 'Scramble for Africa' had begun. Adam Hochschild is an American writer and journalist for the New Yorker, NY Times, NY Review of Books and Times Literary Supplement. His work has combined history with human rights advocacy. The events in this book are a shameful chapter in an era of colonialism of which there were many. It is portrait of Leopold II likely to inspire loathing in anyone who reads it. Beside an account of a colony he archives lives of activists who fought for freedom.

In 1482 Portuguese sailors braved the ocean beyond the Canary Islands and discovered a fresh water flow off the coast of Central Africa. Following a silt trail, fighting a fast current, they found the mouth of a vast river. Nine years later priests and emissaries arrived and began the first European settlement in a black African kingdom. Small scale slavery existed but a booming slave trade developed with the Americas to grow cotton and cane. During the 19th century slavery was abolished in Britain and America yet continued in Afro-Arab commerce.

Leopold II (1835-1909) was the King of the Belgians and obsessed with obtaining colonies. He studied records of the conquistadores in Seville, sailed to India, Ceylon, Burma and Java noting lucrative concerns. Plantations depended on forced labor to lift profits and civilize the lazy natives. He looked at land in Brazil, Argentina, Philippines and Taiwan. Frustrated in these attempts he focused his sights on Africa. Humanitarian pretenses of freeing Africa from slavery and bringing enlightenment to the Dark Continent disguised his dreams of ivory and rubber.

Henry Morton Stanley led a Dickensonian life. Abandoned to a poorhouse as a child he sailed to America and was a soldier in the Civil War, first for the Confederacy and then for the Union. He became a newspaper correspondent and tracked down explorer David Livingstone during his search for the source of the Nile. Returning to Africa in 1874 to map the waterways of the interior he discovered the source of the Congo River. Upon reaching the Atlantic he was hired by Leopold to establish trading posts, build railroads and trick tribal leaders to cede land.

King Leopold and an American ambassador formed fake philanthropic associations for evangelism and scientific study of the region. In 1884 he lobbied the US to recognize the Congo Free State, in reality a colony owned by himself. Post-Civil War politicians were interested in sending freed slaves back to Africa. The area annexed was as large as the land east of the Mississippi, while Belgium was half the size of West Virginia. In diplomatic dealing France and Germany fell into line and Britain became invested. The challenge was to carry steamboats over the falls.

By 1890 trading stations had been secured. Elephants were hunted by conscripted natives or their ivory simply seized. Vacant land was leased to private companies with shares of the profit retained. Legions of Africans were used as porters through jungles chained by the neck. So many were needed agents began to purchase them from the slave traders they purported to abolish. Security officers of the Free State were Europeans, half from Belgium, with soldiers drawn from the Congo. They chose to join the conquerors, their spears and shields no match for machine guns.

Leopold's agents set up orphanages run by Catholic missions to train future troops. Captured women were kept in harems by agents, or held as hostages to coerce their men to harvest rubber. Discipline was enforced with the whip and counted in severed hands of dead rebels. To exact penalties entire villages were often burned down. Their death toll over a quarter century is not known for certain but is estimated at 10 million, or half of the population. The causes included murder, starvation and disease, due to inhumane working conditions and lowered birth rates.

Joseph Conrad was briefly a steamboat pilot on the Congo, his novel 'Heart of Darkness' a depiction of what he saw. Displays of decapitated heads were not only a metaphorical critique of colonialism. Black Americans G.W. Williams, a polymath, and W.H. Sheppard, a missionary, exposed the conditions in 1890. Few voices of natives were recorded but are included where possible. In 1898 British shipping clerk E. D. Morel and Irish diplomat R. Casement suspected forced labor and began campaigns. Mark Twain and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote exposés on Leopold.

As opinion turned Leopold waged propaganda wars. Self-appointed commissions criticized his regime. The only option was to sell the Congo to Belgium as self rule was unthinkable. In 1908 Leopold was given a billion dollar bonus and billions remained in his name. Wild rubber was replaced with farmed. Atrocities declined but forced labor persisted. Head taxes kept people in mines and plantations until independence in 1960. PM Lumumba, seen as hostile to business, was killed by Belgians with US assistance and replaced by kleptocrat Mobuto until 1997.

africa

colonialism

66 likes

2 comments

===

No comments:

Post a Comment