Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion by Gareth Stedman Jones – review | Books | The Guardian

Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion by Gareth Stedman Jones – review

Karl Marx’s true dreams and the ideology that bears his name are very different things, according to this exhaustive biography

Oliver Bullough

@oliverbullough

Sun 14 Aug 2016 16.30 AESTLast modified on Thu 22 Mar 2018 10.59 AEDT

Shares

702

Comments64

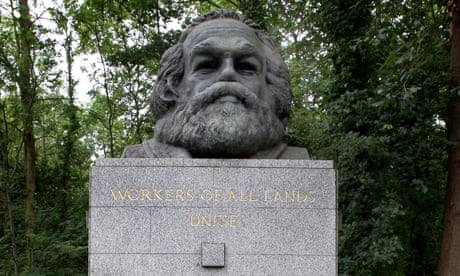

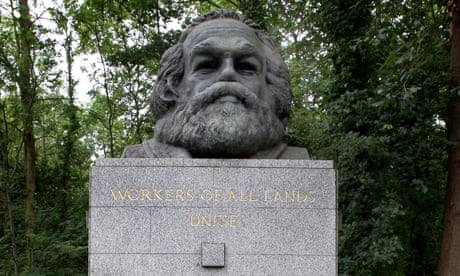

Karl Marx: once the mane man. Photograph: Imagno/Getty Images

When I lived in Moscow, I more often than not walked to work down Okhotny Ryad, a grand central boulevard. Like many places in Russia, it had been renamed after 1991 as part of a push to remove anything redolent of communism from the map. Like many de-Sovietising initiatives, however, the process was abandoned halfway through. Karl Marx Avenue might have become Okhotny Ryad, but a statue of the man who inspired the Soviet regime stayed in situ, a few yards away from the traffic, where the road meets Theatre Square.

The statue’s plinth proclaims: “Workers of the world, unite!” The statue itself shows him with flowing locks swept back from his forehead as if by a stiff breeze, above a full beard, all hewn ruggedly out of granite. This statue formed an occasional focal point for slightly forlorn demonstrations by some of Russia’s remaining communists, who waved their red flags and demanded that Vladimir Putin resign.

I sometimes thought, when looking at their demonstrations as I walked by, that de-Sovietisers could still solve the problem if they wanted, by just affixing a different slogan over the communist one and pretending the statue didn’t represent Marx at all. With his bushy beard and beetling brow, the great communist could easily be a mystic from the early days of Orthodox Christianity (though, admittedly, the greatcoat and tie would be hard to explain). That’s the thing about Marx – he looks right; he looks like you’d expect a prophet to look. Before you even hear the details of his arguments, you find yourself thinking: someone with that much hair has to have a point.

The magnificence of Marx’s mane has clearly long been a major part of his personal brand. It graces his grave in Highgate cemetery and here it is again, adorning the cover of Gareth Stedman Jones’s exhaustive and staggeringly well-researched intellectual biography. Stedman Jones is professor of the history of ideas at Queen Mary, University of London, and has long focused on Marx. This book is an attempt to separate the man (whom he calls “Karl” throughout, thus distinguishing him from the mythical “Marx”) from the Marxist movement he inspired.

------------

Karl Marx was born in 1818 in Trier, a town in the Rhineland-Palatinate (a western province of what is now Germany), which had recently been added to the Kingdom of Prussia, having been held by France since shortly after the French revolution. The Napoleonic wars had only just finished and Europe was entering into a turbulent period, full of industrial innovation, revolutionary activities, philosophical debates and more. Growing up, Marx was a precocious student who befriended many of the leading German-speaking philosophers of the time. By his late 20s, he was describing himself as a communist and engaging in heated debates with fellow travellers who raised points he disagreed with, often so forcefully that they barely recovered from the experience.

The revolutionary upheavals of 1848 carried him across western Europe – France, Belgium, Germany – until eventually he ended up in London, where he attempted to write up his unifying theory of humanity’s progress towards a socialist utopia that still inspires those protesters around his statue in Moscow. He had already met Friedrich Engels (who also frequently appears as a Russian statue, despite being less hirsute), who became both his closest intellectual collaborator and the source of much of the money he lived on.

I couldn’t help noticing some clear parallels between modern leftist politics and the habits of the old man

Marx had a restless intellect and he constantly sought to fit the world into his worldview. It was an effort so enormous it quite destroyed his health. By the end of his life, he was largely avoiding talking about work to his well-wishers, since they would only ask when he would produce more of it.

----------

Stedman Jones argues that much of what we now think of as Marxism – and, thus, much of what went on to inspire socialist and communist parties – was the creation of Engels, who codified Marx’s theories after his death, thus making them palatable for people unable or unwilling to wade through his dense texts. It was Engels, for example, who insisted on drawing parallels between Marx and Charles Darwin, when Marx himself was far from convinced of the importance of the theory of natural selection.

When I lived in Moscow, I more often than not walked to work down Okhotny Ryad, a grand central boulevard. Like many places in Russia, it had been renamed after 1991 as part of a push to remove anything redolent of communism from the map. Like many de-Sovietising initiatives, however, the process was abandoned halfway through. Karl Marx Avenue might have become Okhotny Ryad, but a statue of the man who inspired the Soviet regime stayed in situ, a few yards away from the traffic, where the road meets Theatre Square.

The statue’s plinth proclaims: “Workers of the world, unite!” The statue itself shows him with flowing locks swept back from his forehead as if by a stiff breeze, above a full beard, all hewn ruggedly out of granite. This statue formed an occasional focal point for slightly forlorn demonstrations by some of Russia’s remaining communists, who waved their red flags and demanded that Vladimir Putin resign.

I sometimes thought, when looking at their demonstrations as I walked by, that de-Sovietisers could still solve the problem if they wanted, by just affixing a different slogan over the communist one and pretending the statue didn’t represent Marx at all. With his bushy beard and beetling brow, the great communist could easily be a mystic from the early days of Orthodox Christianity (though, admittedly, the greatcoat and tie would be hard to explain). That’s the thing about Marx – he looks right; he looks like you’d expect a prophet to look. Before you even hear the details of his arguments, you find yourself thinking: someone with that much hair has to have a point.

The magnificence of Marx’s mane has clearly long been a major part of his personal brand. It graces his grave in Highgate cemetery and here it is again, adorning the cover of Gareth Stedman Jones’s exhaustive and staggeringly well-researched intellectual biography. Stedman Jones is professor of the history of ideas at Queen Mary, University of London, and has long focused on Marx. This book is an attempt to separate the man (whom he calls “Karl” throughout, thus distinguishing him from the mythical “Marx”) from the Marxist movement he inspired.

------------

Karl Marx was born in 1818 in Trier, a town in the Rhineland-Palatinate (a western province of what is now Germany), which had recently been added to the Kingdom of Prussia, having been held by France since shortly after the French revolution. The Napoleonic wars had only just finished and Europe was entering into a turbulent period, full of industrial innovation, revolutionary activities, philosophical debates and more. Growing up, Marx was a precocious student who befriended many of the leading German-speaking philosophers of the time. By his late 20s, he was describing himself as a communist and engaging in heated debates with fellow travellers who raised points he disagreed with, often so forcefully that they barely recovered from the experience.

The revolutionary upheavals of 1848 carried him across western Europe – France, Belgium, Germany – until eventually he ended up in London, where he attempted to write up his unifying theory of humanity’s progress towards a socialist utopia that still inspires those protesters around his statue in Moscow. He had already met Friedrich Engels (who also frequently appears as a Russian statue, despite being less hirsute), who became both his closest intellectual collaborator and the source of much of the money he lived on.

I couldn’t help noticing some clear parallels between modern leftist politics and the habits of the old man

Marx had a restless intellect and he constantly sought to fit the world into his worldview. It was an effort so enormous it quite destroyed his health. By the end of his life, he was largely avoiding talking about work to his well-wishers, since they would only ask when he would produce more of it.

----------

Stedman Jones argues that much of what we now think of as Marxism – and, thus, much of what went on to inspire socialist and communist parties – was the creation of Engels, who codified Marx’s theories after his death, thus making them palatable for people unable or unwilling to wade through his dense texts. It was Engels, for example, who insisted on drawing parallels between Marx and Charles Darwin, when Marx himself was far from convinced of the importance of the theory of natural selection.

Stedman Jones develops his argument very gradually, with regular stops to survey the intellectual milieu in which Marx was working. Many of the characters are obscure, so parts of the book are perhaps best suited to people who already know a significant amount about the history of 19th-century philosophy.

Stedman Jones eventually comes to the conclusion that the pioneers of 20th-century socialism would have found Marx’s true dreams incomprehensible, since they were formed in a pre-1848 world that would have had little if any relevance to them. The eventual message is that Marxist ideology and Marx himself were very different things.

I couldn’t help noticing while reading the book, however, some clear parallels between modern leftist politics and the habits of the old man. Thanks to his obsession with minute points of ideological deviation, his determination to cling to leadership positions despite the increasing irrelevance of the groups he led, his conviction that victory was imminent despite near-overwhelming evidence to the contrary, and his repeated estrangement of potential allies for no apparent reason, Marx would surely have felt at home in today’s Labour party.

Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion is published by Allen Lane (£35). Click here to buy it for £28.70

Stedman Jones eventually comes to the conclusion that the pioneers of 20th-century socialism would have found Marx’s true dreams incomprehensible, since they were formed in a pre-1848 world that would have had little if any relevance to them. The eventual message is that Marxist ideology and Marx himself were very different things.

I couldn’t help noticing while reading the book, however, some clear parallels between modern leftist politics and the habits of the old man. Thanks to his obsession with minute points of ideological deviation, his determination to cling to leadership positions despite the increasing irrelevance of the groups he led, his conviction that victory was imminent despite near-overwhelming evidence to the contrary, and his repeated estrangement of potential allies for no apparent reason, Marx would surely have felt at home in today’s Labour party.

Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion is published by Allen Lane (£35). Click here to buy it for £28.70

No comments:

Post a Comment