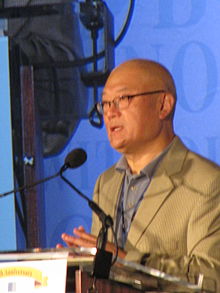

Ha Jin

Ha Jin

哈金 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 金雪飞 February 21, 1956 Liaoning, China |

| Pen name | Ha Jin |

| Occupation | Poet, novelist, teacher |

| Nationality | United States |

| Education | Doctor of Philosophy |

| Alma mater | Heilongjiang University Shandong University Brandeis University |

| Genre | Poetry, short story, novel, essay |

| Subjects | China |

| Notable works | |

| Notable awards | |

| Signature |  |

Xuefei Jin (simplified Chinese: 金雪飞; traditional Chinese: 金雪飛; pinyin: Jīn Xuěfēi; born February 21, 1956) is a Chinese-American poet and novelist using the pen name Ha Jin (哈金). Ha comes from his favorite city, Harbin. His poetry is associated with the Misty Poetry movement.[1]

Early life[edit]

Ha Jin was born in Liaoning, China. His father was a military officer; at thirteen, Jin joined the People's Liberation Army during the Cultural Revolution. Jin began to educate himself in Chinese literature and high school curriculum at sixteen. He left the army when he was nineteen,[2] as he entered Heilongjiang University and earned a bachelor's degree in English studies. This was followed by a master's degree in Anglo-American literature at Shandong University.

Jin grew up in the chaos of early communist China. He was on a scholarship at Brandeis University when the 1989 Tiananmen incident occurred. The Chinese government's forcible put-down hastened his decision to emigrate to the United States, and was the cause of his choice to write in English "to preserve the integrity of his work." He eventually obtained a Ph.D.

Career[edit]

Jin sets many of his stories and novels in China, in the fictional Muji City. He has won the National Book Award for Fiction[3] and the PEN/Faulkner Award for his novel, Waiting (1999). He has received three Pushcart Prizes for fiction and a Kenyon Review Prize. Many of his short stories have appeared in The Best American Short Stories anthologies. His collection Under The Red Flag (1997) won the Flannery O'Connor Award for Short Fiction, while Ocean of Words (1996) has been awarded the PEN/Hemingway Award. The novel War Trash (2004), set during the Korean War, won a second PEN/Faulkner Award for Jin, thus ranking him with Philip Roth, John Edgar Wideman and E. L. Doctorow who are the only other authors to have won the prize more than once. War Trash was also a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

Jin currently teaches at Boston University in Boston, Massachusetts. He formerly taught at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

Jin was a Mary Ellen von der Heyden Fellow for Fiction at the American Academy in Berlin, Germany, in the fall of 2008. He was inducted to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2014.

Awards and honors[edit]

- Flannery O'Connor Award for Short Fiction (1996)

- Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award (1997)

- Guggenheim Fellowship (1999)

- National Book Award (1999)[3]

- PEN/Faulkner Award (2000)

- Asian Fellowship (2000–2002)

- Townsend Prize for Fiction (2002)

- PEN/Faulkner Award (2005)

- Fellow of American Academy of Arts and Sciences (2006)

- Dayton Literary Peace Prize, runner-up, Nanjing Requiem (2012)[4]

- PEN Oakland Josephine Miles Literary Award for A Distant Center (2019)

Books[edit]

Poetry[edit]

Short story collections[edit]

| Novels[edit]

Biographies[edit]

Essays[edit]

|

See also[edit]

- Saboteur (short story) (2000)

References[edit]

- ^ A Brief Guide to Misty Poets Archived 2010-04-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ha Jin" Archived 2010-01-31 at the Wayback Machine. Bookreporter.

- ^ a b "National Book Awards – 1999" Archived 2018-11-24 at the Wayback Machine. National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-27.

(With acceptance speech by Jin and essay by Ru Freeman from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog.) - ^ Julie Bosman (September 30, 2012). "Winners Named for Dayton Literary Peace Prize". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2012-10-02. Retrieved 2012-09-30.

- John Noell Moore, "The Landscape Of Divorce When Worlds Collide," The English Journal 92 (Nov. 2002), pp. 124–127.

- Ha Jin, Waiting (New York: Pantheon Books, 1999)

- Neil J Diamant, Revolutionizing the Family: Politics, Love and Divorce in Urban and Rural China, 1949-1968(Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000), p. 59.

- Ha Jin, The bridegroom (New York: Pantheon Books, 2000)

- Yuejin Wang, Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews 13 (Dec. 1991)

- Ha Jin, "Exiled to English" (New York Times, May 30, 2009)

External links[edit]

- "Ha Jin, The Art of Fiction No. 202". The Paris Review (Interview) (191). Interviewed by Sarah Fay. Winter 2009.

- "The Bridegroom". Bookworm (Interview). Interviewed by Michael Silverblatt. KCRW. January 2001.

- Listen to Ha Jin on The Forum from the BBC World Service

- Boston University staff page

- Author interview in Guernica Magazine (guernicamag.com)

- Ha Jin audio interview re: A Free Life, November 2007

- Exiled to English

- Audio: Ha Jin in conversation on the BBC World Service discussion programme The Forum

- "Ha Jin's Cultural Revolution" - New York Times Magazine profile (2000).

- Ha Jin at Library of Congress Authorities — with 20 catalog records

Ha Jin’s Self-Revealing Study of the Chinese Poet Li Bai

By Han ZhangFebruary 4, 2019

In his biography of Li Bai, the novelist Ha Jin narrates the banished poet’s unusual life, which, in some ways, mirrors the biographer’s.Photograph from Alamy

In his biography of Li Bai, the novelist Ha Jin narrates the banished poet’s unusual life, which, in some ways, mirrors the biographer’s.Photograph from AlamyIn 724 A.D., the twenty-three-year-old poet Li Bai got on a boat and set out from his home region of Shu, today’s Sichuan province, in search of Daoist learnings and a political career. He wasn’t headed anywhere in particular. Instead, he began a life of roaming—hiking up mountains to Daoist sites, meeting men of letters all over the country, and leaving behind hundreds of poems about his travels, his solitude, his friends, the moon, and the pleasures of drinking wine. In the centuries since, Li’s verse, by turns playful and profound, has made him China’s most beloved poet.

In “The Banished Immortal,” a biography of Li, the novelist Ha Jin narrates the poet’s unusual life with erudition and empathy. Jin, a National Book Award-winning writer, is most known for his fiction, which is largely set in China during the Cultural Revolution and in Chinese immigrant communities in the U.S. One might easily take “The Banished Immortal,” his first work of nonfiction, as a departure from his previous work. But a close reading suggests that it is a return to his early themes, and a tribute to the poet he was before making his mark as a novelist. In some ways, the banished poet’s life even mirrors the biographer’s.

That mirroring, though never made explicit, arrives early in the book. Jin, recounting Li’s leaving his home town and venturing into the wilderness, writes, “As he was sailing down the Yangtze, he must have sensed that he was about to become rootless. He would have to accept his homelessness in this world.” This is a striking observation, especially from Jin, whose controlled prose usually avoids speculation. One suspects that the sentiment comes not from the established writer Ha Jin but from the wounded immigrant poet he was, in the nineteen-eighties, when he first came to the U.S., for doctoral work. At the time, Jin was in his twenties, and, in 1989, he watched the Tiananmen Massacre from afar—not knowing what would happen to his home, and, like Li, not knowing if it was home anymore.

Li Bai lived most of his life during the peak of the Tang Dynasty, an era known for its openness, commerce, and thriving literary scene, and his travels included a string of meetings with state officials. Li was convinced after each of these meetings that he’d soon launch his political career. But what made him a poet might have ruined him as a politician. He lived unconventionally—drinking wine into the night, wandering around after curfew, mingling with people from all walks of life. He was always deemed too free-spirited to be a safe candidate for office. Even Jin’s restrained tone can’t obscure Li’s extravagant life, which saw the poet ping-pong between pawning clothes for cups of wine and having the Emperor serve him a ladle of soup. In times of disappointment, his faith kept him afloat. He wrote, “Heaven begot a talent like me and must put me to good use / And a thousand cash in gold, squandered, will come again.” Sometimes his confidence seems close to egomaniacal: when a summons from the imperial court came, he gloated, “laughing out aloud with my head thrown back, / I walk out the front gate. How can a man / Like myself stay in the weeds for too long?”

Li’s fortunes soured in 755, when the general An Lushan began a rebellion that would lead to a period of profound political instability. Amid the conflict, the Emperor’s sons vied for the throne; one of them, Prince Young, recruited Li to be a top adviser, which Li hoped would be his big break in politics. But he was joining the losing side. Prince Young’s elder brother, Emperor Suzong, prevailed, and Li was captured and eventually banished. Believing that he was treated unfairly, Li was also disillusioned by the corrupted court, where the suffering of common people was rarely acknowledged. He didn’t write many poems after that, but, when he did, he often shifted his focus from heavenly images to earthly scenes. Once, when staying at an old acquaintance’s house, he observed the harsh life of an ordinary family: “The peasant families have to work hard. The woman next door keeps pounding rice in the cold. My hostess kneels to serve me wild rice, Moonlight shining on the full white plate.”

For Jin, Tiananmen marked a similar disruption, both in his life and in his work. After the massacre, he hastened to bring his family Stateside. When his six-year-old arrived, he and his wife were forced to explain the move; in a poem, Jin recalls his wife telling their child, “They killed people like us.” When Jin later tried to visit China, his visa was repeatedly denied. He finally gave up when his mother, who hadn’t seen him for almost thirty years, died in 2014. Around the time of Tiananmen, Jin also decided to begin writing in English, and many of his later novels (“A Map of Betrayal,” “A Free Life”) see him inhabit Chinese-Americans thrust into a confrontation with their homeland.

In 1993, when Jin graduated, with a Ph.D. in English, he fantasized about a future rich in opportunity. Reality soon intervened: he landed only one interview and didn’t hear back. It was then that he thought of Li Bai (or Li Po, as the poet is known in the West) and began to see hardship as a path to literary excellence. In a poem called “Gratitude,” Jin writes:

I remembered the fate of Tu Fu and Li Po—

two great poets who had the bitterest lives.

The Lord of Heaven wanted them to sing,

so he made them feed on misfortune.

He continues:

I said to myself: This must be another trick

Heaven plays on you, to make your words come

not from a sore throat, but from a twinging belly.

In the same poem, Jin found something else in common with Li: “Those ancient masters were also forced to leave home.” The state of exile, even when chosen, came with mourning. Li Bai’s poems are filled with reunions and partings, rapture and sorrow, and they tend to suggest that we are alone and lost in the world. When seeing off his friend, the prominent poet Meng Haoran, Li conjured this image: “His sail casts a single shadow in distance, then disappears, / Nothing but the Yangtze flowing on the edge of the sky.” Li, like Jin, never returned to his home. But he certainly missed it. One of his most celebrated poems sees the writer contemplate a quiet night:

Moonlight spreads before my bed.

I wonder if it’s hoarfrost on the ground.

I raise my head to watch the moon

And lowering it, I think of home.

Ha Jin might have thought of this poem during cold nights outside Boston. (In “To an Ancient Chinese Poet,” he imagines Li Bai on a drunken night with a shy moon. “What’s the use of fame as a poet?” Jin hears the poet pondering. “It’s a silent affair a thousand years after me.”) And yet Jin’s work usually rejects such nostalgia. In his book of essays, “The Writer as Migrant,” from 2008, he writes, of those who can no longer return to their homes, “Their ships are gone, and left on their own in a new place, they have to figure out their bearings and live a life different from that of their past.” Once the migrants have left, they must embrace their plight. “The acceptance of rootlessness as one’s existential condition,” Jin writes, “exemplifies the situation most migrant writers face.”

War Trash

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search

War Trash

First edition cover

Author Ha Jin

Country United States

Language English

Genre War novel

Publisher Pantheon Books

Publication date 2004

Media type Print (Hardcover)

Pages 352 pp

ISBN 0-375-42276-5

OCLC 54529825

Dewey Decimal 813/.54 22

LC Class PS3560.I6 W37 2004

War Trash is a novel by the Chinese author Ha Jin, who has long lived in the United States and who writes in English. It takes the form of a memoir written by the fictional character Yu Yuan, a man who eventually becomes a soldier in the Chinese People's Volunteer Army and who is sent to Korea to fight on the Communist side in the Korean War. The majority of the "memoir" is devoted to describing this experience, especially after Yu Yuan is captured by United Nations forces and imprisoned as a POW. The novel captured the PEN/Faulkner Award and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

Contents

Plot summary

1 Prisoner with the Nationalists

2 Working for the Communists

3 To the Nationalists, and Back Again

4 Bittersweet Return to China

Plot summary[edit]

Yu Yuan was originally a cadet at Huangpu Military Academy, an important part of the Kuomintang military system. However, when the Communists gained the upper hand in China, the academy went over to their side, and Yu was made a part of the PLA. He is eventually sent to Korea as a lower-ranking officer in the 180th Division. Since he knew some English, he is made part of his unit's staff as a possible translator. He left behind his mother and his fiancee, a girl named Tao Julan.

Yu Yuan's unit eventually crosses into Korea and engages the South Korean and UN forces there. After the unit is encircled and destroyed, Yu Yuan is injured and is captured. He spends some time in a hospital, where the ministrations of the medical staff impress him with the humane nature of the medical profession.

Subsequently, Yu Yuan is put in a prisoner of war camp. A major political fault line ran through the Communist prisoners, both historically and in the novel. On one side are those who are "loyal" and wish to be repatriated to the Communist side, either North Korean or Chinese; these are called "pro-Communists". On the other side are those who wish to be released to the "Free World", whether that be South Korea or the remaining Chinese Kuomintang bastion of Taiwan. This group is called "pro-Nationalists". Violence often flares between these two groups, and the chief tension in the book is the narrator's attempts to navigate this political minefield.

Prisoner with the Nationalists[edit]

After his capture, Yu Yuan is registered as a POW in the city of Pusan. He assumes a false identity, in order to hide his rank as a low-level officer. All captured officers give their names and try to mix in with enlisted men so that they will not be subject to questioning and torture by the captors. He is then taken to the island of Guh-Jae-Do, which was cleared of most civilians in order to house POWs captured by the South Korean military.

Yu Yuan initially finds himself in the pro-Nationalist camp, somewhat against his will. This is not because he is politically passionate, but rather because his main goal is to return home to his mother and fiancee. Going to Taiwan would politically taint him in Communist China and make such a return impossible. His association with Huangpu lends him some breathing room, but when he states his intention to return to mainland China, he is kidnapped by the Nationalists and tattooed with the words "FUCK COMMUNISM" in English.

A decision is made by the administrators of the camp to conduct a "screening" to divide the Nationalists and Communists in the camp and hopefully reduce violence. This period before the screening is an intense time for the camp, as the leadership of both sides wants to convince the prisoners to choose the correct side, thus scoring a propaganda victory. Yu Yuan witnesses incredible acts of torture and coercion committed by pro-Nationalist officers, but motivated by a longing for home, he chooses the Communist side.

Working for the Communists[edit]

Now in a Communist camp, Yu Yuan is suspected for his Huangpu ties and his stint with the Nationalists. However, his skills in English are useful and he eventually gains the trust of his superiors. The coordination of the camp is much better than before, and the prisoners organize themselves for resistance. However, they cannot compete with the camp of the North Koreans, who due to their greater local knowledge and better underground networks can carry out stunning logistical feats and are in communication with their capital Pyongyang.

Eventually, the North Koreans organize an attempt to kidnap General Bell, the commandant of all the prisoner of war camps. (This is a reference to the historical attempt to capture the American General Francis T. Dodd). They enlist the participation of the Chinese camp through a meeting of emissaries. As a mark of the trustworthiness of Yu Yuan, Commissar Pei, the leader of the Chinese pro-Communist camp, sends Yu Yuan as his representative. The Chinese camp gathers information and passes it to the North Korean camp, which subsequently lures Bell in for negotiations, then kidnaps him, a propaganda coup for the Communists.

Soon, the prisoners are sent to better organized camps on Cheju Island. The facilities are better, but the methods of prisoner control are also enhanced, making it harder to resist. Commissar Pei, for instance, is separated from the men. Also, the prisoners begin to feel very isolated from their country, and worry that they will be treated with suspicion when they return to China, as it can be considered treason to be captured rather than fight to the death. However, with ingenious methods of communication developed, Commissar Pei manages to send orders to raise homemade Chinese communist flags on national day, a provocation which creates a confrontation and raises morale, even though lives are lost in the ensuing battle.

To the Nationalists, and Back Again[edit]

At some point a small group of pro-Communist officers—including Commissar Pei's right-hand man, Party member Chang Ming—is ordered to Korea to "re-register". Fearing that this will permanently strip him of his English-speaking lieutenant, Pei orders Yu Yuan to assume Ming's identity and go in his place. Fuming at being sacrificed like a pawn for a man no different from him except for Party membership, Yuan obeys and is sent to Korea. It turns out that "re-registering" is not something sinister, but rather bureaucratic processing. However, the subterfuge of "Ming" is discovered and in the confusion he declares his dislike of the Communists. As a result, he is now sent to the Nationalist camp back of Koje Island.

Back with the Nationalists again, Yuan is subject to another round of suspicion for siding with the Communists earlier. He weathers this (due in part to his tattoo, which he has kept after having it cleared with the Communists). The officers on the Nationalist side hope that his credentials will elevate him once they get to Taiwan, and in this position he might be able to help them. During this time, the armistice is signed by the UN and North Koreans, and the prisoners begin to look forward, with hope and anxiety, towards their repatriation.

Required yet again to declare his allegiance, Yu Yuan, as always, is in a delicate situation. His time on the Communist side means he will always be politically damaged goods in Taiwan, forever handicapped. On the other hand, unless Pei and Ming are still alive and in the good graces of the Party—and therefore able to explain that the Party ordered him to be re-registered—his "defection" to the Nationalists (as well as the lingering taint of being a prisoner in the first place) could be politically devastating if he returns home. He hears that there may be a third option, to emigrate to a neutral country. Quietly, he makes this his plan.

However, when Yu Yuan first enters the tent where declarations must be made, he finds that one of the Communist Chinese observers is a friend of his who instantly recognizes him! No longer anonymous, he realizes that if he chooses a third country, his disloyal choice will be traced to his family and they will suffer. Encouraged by his friend about the treatment prisoners receive in China, he makes the decision to return home on the spot.

Bittersweet Return to China[edit]

Yu Yuan's homecoming is not what he had hoped in the more than two years he had been away. His superiors stand up for him, witnessing to the pro-Communist acts he had carried out. However, as party members they are severely tainted (party members swore an oath to fight to the death, and thus their capture is even more dishonorable) and their evidence is worthless. Yu Yuan finds out that his mother has died, and Julan has deserted him as a disgrace. Forever marked by his disloyalty, he is unable to use his college education well, and quietly becomes a teacher.

In the epilogue-like final chapter, Yu Yuan describes his eventual marriage, and children. He is not so tainted that he cannot get his offspring into college, and eventually his son goes to the United States for education. Yuan gets his tattoo changed to FUCK...U...S by erasing some of the letters of COMMUNISM. An old man, he learns of the ruin of his communist superiors, and of the success of some of his Nationalist acquaintances in Taiwan. Eventually, he visits his son in America, giving opportunity for one last comical difficulty with his tattoo, once again highly inappropriate. It is here that he finds the time to write the memoir, dedicated to his American grandchildren, which the reader has been enjoying.

------------------

밑줄긋기, 하진의 《전쟁쓰레기》

by sebin

2008/10/18 16:20

bakku.egloos.com/3946710

덧글수 : 9

근래 몇년간 읽은 소설 중 가장 인상적인 소설이 될 것 같다. (그리고 돈 주고 사기에 가장 가치있는 소설) 한국전쟁의 또다른 당사자였던 한 중국인의 시각으로 쓰여진, 픽션이지만 그 모든 현실보다 더욱 현실적인 글이었다. 물론 내가 거의 모르는 현실을 그린. 솔직히 말하면 89천안문사태 이후 중국에 돌아가지 않기로 결정하고 미국에 눌러앉은, 미국 대학의 영문학 교수라는 그의 프로필을 보고 휴머니즘으로 버무림된, 그러면서도 지식인 입장에서 바라본 공산당에 대한 멸시나 자괴감으로 가득한 글이 아닐까 하는 선입견을 갖고 책장을 넘기기 시작했다는 것을 부정할 수 없다. 하지만 책장이 넘어가면서, 특히 결말 부분에 있어서 주인공 유안이 포로 송환 과정에서 내린 선택의 순간은 고향을 등지고 미국을 택한 작가에 대한 내 괜한 편견이 여지없이 깨지는 순간이기도 했다. 한국전쟁이라는 시대의 격랑 속에 아주 나약한 개인으로서의 경험, 그 시기를 살아가던 중국인 지식인, 혹은 평범한 사람들-한국인을 포함하여-의 고민, 왼쪽과 오른쪽, 이념의 혼돈 등은 작가가 한국전쟁 이후에 태어나, 이를 겪어보지 못한 사람이라는 것을 믿을 수 없게 한다.

모순에 가득찬 그시절 공산당의 모습에서 내가 원하고 70~80년대에 우리가 원했던 공산당의 모습이 아니라는 점은 실망과 안타까움이 생길 수밖에 없다. 아마 관념적 공산주의에 매몰됐던 그 시기에는 중국이 아니라 어디라도 그랬겠지만, 그들의 공산주의에 1밀리그램의 자비와 인간애가 있었더라면 지금 세계의 모습이 조금 더 나아져 있지는 않았을까 하는 생각에 가슴이 아프다. 아마 작가도 그랬던 게 아닐까. 글 곳곳에서보이는 공산주의에 대한 유안의 실날같은 기대와 그것이 번번이 무너지는 모습은 유안의 안타까움일까, 작가의 안타까움일까, 지금을 사는 중국 지식인들의 안타까움일까.

다만 이런 책을 시공사가 낸다는 건 좀 싫다. 시공사는 그냥 만화, 소설이나 팔았으면 좋겠다.

아래는 몇몇 부분들의 발췌.

---

"좋아, 이제부터 자네는 이 사람들하고 있게."

그는 나를 두 번 다시 쳐다보지도 않고 가버렸다. 나는 이 작고 허름한 천막에는 본토 송환을 원하는 수감자들만 있다는 걸 알았다. 우리가 이곳에서 소수라는 건 분명했다. 타이완에 가기로 작정한 국민당 동조자들은 본토로 돌아가려고 하는 사람은 누구나 공산주의자이거나 공산주의에 동조하는 사람이라고 생각했다. 하지만 우리들 대부분은 정치적인 이유로 고향에 가고자 하는 게 전혀 아니었다. 우리의 결정은 개인적인 것이었다.

"그것 보라고. 공산주의자들은 너 같은 외아들도 군대에 오게 했다. 그들은 사람을 총알받이로 이용하지. 염병할 놈들. 우리 사단은 지난 봄에 있었던 영국군 대대와의 전투에서 1천 명이 넘는 사람들의 목숨을 희생시켰다. 언덕 기슭에 피가 너무 많이 흘러서 다음날 아침에 보니까 수백 마리 까마귀들의 날개가 시뻘겋더라. 그래도 고위층들은 우리가 결국 적의 지대를 함락시켰다며 그걸 승전이라고 하더라."

"맞는 말씀입니다. 저는 그렇게 많은 중국인들이 한국 땅에 묻힐 거라고는 생각한 적이 없습니다."

그의 말은 내가 도저히 떨쳐내지 못하는 끔찍한 이미지를 불러일으켰다. 전쟁은 군인들의 시체를 연료로 삼는 거대한 용광로였다.

"펭얀, 내 부탁 하나 들어줄 수 있어?"

"물론이죠, 가능하다면."

나는 무력한 포로인 내가 그에게 어떤 도움을 줄 수 있다는 건지 의아스러웠다. 그가 살짝 웃으며 말했다.

"이 염병할 놈의 전쟁이 다시 과열되면, 나는 전방으로 갈 수도 있어. 내가 안전증서 얻는 걸 도와줄 수 있겠어?"

"그게 뭔데요?"

"모른단 말이야?"

"정말 모르겠는데요."

"나도 본 적은 없어. 하지만 중국어나 한국어로 '이 사람을 죽이지 마라. 그는 우리의 친구다' 이렇게 쓰여 있다고 하더군."

"그걸 어디다 쓰려고요?"

"당신네 중국인들은 포로들을 죽이잖아. 나는 한 장교가 전선에서 연대 병력을 잃어버렸다는 이유로 40명이 넘는 미군 포로들을 죽였다는 얘기를 들은 적이 있어. 내가 그들한테 사로잡힐 경우, 당신이 준 종이를 보여주면 그들이 나를 죽이지 않을 수도 있잖아."

그의 솔직한 말에 깜짝 놀랐다. 하지만 나는 아무 말도 하지 않고 도와주겠다고만 약속했다. 나는 그가 아무런 수치심이나 당혹스러움 없이 자신이 두려워하는 것에 대해 얘기할 수 있다는 게 존경스러웠다.

우리는 한국 여자들에 관해 얘기했다. 우리는 한국 여자들이 화장을 안 하기 때문에 만추리아의 여자들보다 예뻐 보이지 않는다고 생각했다.

"그들 중 상당수는 얼굴이 햇볕에 탔잖소."

참모장교가 뭔가 냄새를 맡는 것처럼 납작한 코에 주름을 잡으며 말했다. 그의 목에는 부항을 뜬 큰 자주색 자국이 있었다.

"얼굴은 괜찮아요. 예쁜 여자들도 있고요. 하지만 다리가 벌어졌소. 나는 그게 걸립디다."

마흔 살쯤 되어 보이는 부대대장이 말했다. (중략)

"그들의 생김새는 한국 남자들을 보면 알 수 있죠. 그들도 대부분 다리가 벌어졌어요."

"너무 많이 앉아서 그럴지 몰라요."

내가 끼어들었다.

"그들은 집에 가구가 없어서 늘 바닥에 앉아 지내요. 그래서 다리가 그렇게 됐는지 몰라요."

"그게 맞을 것 같소."

참모장교가 수긍했다.

"그리고 한국 여자들은 거름이 든 소쿠리와 물항아리를 머리에 이고 다녀요. 그래서 등뼈가 눌린 게 틀림없어요."

내가 말했다.

"맞는 말이오."

나이 많은 장교가 말했다.

다리는 벌어졌을지 몰라도 우리는 모두 한국 여자들이 대부분의 중국 여자들보다 좋은 아내가 될 것이라고 생각했다. 우리는 그들의 체구가 대체적으로 작은 이유는 일을 너무 많이 해서 발육을 방해받았기 때문이라고 추측했다. 한국 남자들은 농사일을 거의 하지 않는 것 같았다. 남자 노인들이 달구지를 몰고, 과수원을 지키고, 숱을 만들고, 담배를 건조하고, 산에서 인삼을 재배하는 모습은 자주 볼 수 있었지만, 그들이 모를 심거나 밭에서 잡초를 뽑는 모습은 좀처럼 보기 힘들었다. 게다가 대부분의 젊은 남자들은 징집을 당해 들판은 10대 초반부터 농사일을 시작한 여자들의 손에 맡겨졌다. 하지만 한국인들은 거의 예외 없이 이가 하얗고 튼튼했다. 나는 잇몸에 염증이 자주 있었기 때문에 그걸 눈여겨보았다. 어떤 한국인 의사는 나한테 그들의 이가 건강한 것은 김치 때문이라고 얘기 해줬다.

많은 수감자들이 이 두툼한 앨범을 넘겨가면서 맥아더 장군과 리지웨이 장군에 관한 얘기를 했다. 어떤 이들은 부대를 방문할 때 종종 민간인복차림에 가죽 장갑과 선글라스를 끼고, 실크 목도리까지 두르던 맥아더 장군을 좋아했다. 또 다른 이들은 늘 전투복 차림에 왼쪽 어깨에는 구급상자를 달고 오른쪽 가슴에는 수류탄을 차고 벨트에는 권총과 망원경을 달고 다니는 리지웨이 장군을 좋아했다. 나는 맥아더가 싫었다. 그는 종종 카메라를 향해 만족스러운 웃음을 지어 보였는데, 전쟁을 즐기는 게 분명했다. 전쟁을 하면서도 아주 편안해 보였다. 마치 경기장에 앉아 게임을 즐기고 있는 것 같았다. 민간인복 차림의 그는 전투에 참여하지 않는 사람 같았다. 그는 부하들 위에 군림하며 자기 손을 더럽히기를 머뭇거리는 사람 같았다. 전사보다는 상원의원 같았다. 그를 존경하는 포로들은 리지웨이에 대해 나쁘게 말했다. 그들에 따르면, 그는 쭈글쭈글한 얼굴에 피곤한 눈의 시골뜨기 같다고 했다. 어느 날 나는 열이 받은 나머지 그들에게 물었다.

"당신들은 군인으로서 누구의 지휘를 받으며 싸우고 싶소? 맥아더요, 아니면 리지웨이요?"

맥아더를 선택하는 사람은 아무도 없었다.

퓰리처상까지 탄 걸 보면 유능한 기자였음이 분명했다. 그녀는 오래전에 미국으로 돌아갔지만 아직도 기관지염, 격심한 부비강염, 재발하는 말라리아, 이질, 황달로 고생하고 있다고 했다. 그 모든 병들이 전쟁 중에 기자 생활을 하며 얻은 것들이었다. 한 인터뷰에서 그는 '전쟁처럼 흥분되는 남자'를 만나기 전에는 결혼하지 않겠다고 말했다. (중략) '한국전쟁은 그녀의 전쟁이다' 이런 문장으로 마무리한 기사도 있었다. 누가 전쟁의 무게를 감당할 수 있는가? 증언한다는 것은 진실을 알리는 것이다. 하지만 우리는 대부분의 희생자들이 자신의 목소리를 갖지 못하고 있으며, 우리가 그들의 이야기를 증언하면서 그들을 개인적인 용도로 써서는 안 된다는 걸 기억해야 한다.

공산주의자들과 비교하면 국민당 애호자들은 형식적인 것에 신경을 더 많이 썼다. 그래서 공식 서한은 정교하고 겉보기에 우아해야 했다. 그들은 언제나 상급자에게 편지를 쓸 때는 상대방의 계급을 명시했다. 그런가 하면 서로에게 편지를 쓸 때는 형, 존경하는 형, 자애로운 형 등으로 다양하게 상대방을 불렀다. 편지를 받는 사람이 자신보다 나이가 어린 경우에도 그랬다. 나는 봉건적이고 우스꽝스러운 이러한 종류의 격식이 싫었다. 하지만 그것을 잘 알고 있었기 때문에 쉽게 편지들을 써줄 수 있었다.

상황이 아무리 지옥 같아도, 그것을 더 악화시키는 사람들은 늘 있었다. 이제 나는 이따금 한국의 민간인들이 우리에게 적개심을 갖는 이유를 이해할 수 있었다.

한국인들에게 우리는 단지 중국의 이익을 지키기 위해 이곳으로 온 사람들이었다. 그렇게 함으로써 우리는 그들의 집과 논밭과 살림을 망치지 않을 수 없었다. 그들의 입장에서 볼 때 중국군이 얄루강을 건너오지 않았더라면, 수백만 명의 민간인과 군인들이 목숨을 잃지 않았을 것이다. 물론 미국은 그렇게 되면 한국 영토를 모두 점령하고, 중국으로 하여금 만추리아에서 방어선을 치도록 했을 것이고, 그렇게 되면 중국은 이웃 나라에 병력을 보내 싸우게 하는 것보다 훨씬 더 희생이 컸을 것이다. 결국 한국인들이 이 전쟁에 따르는 파괴의 예봉을 견디는 동안, 중국인들은 우리의 국경 안으로 불길이 들어오지 못하도록 하기 위해 이곳에 와 있는 것이었다. 혹은 대부분의 전쟁포로들이 믿는 것처럼 우리는 러시아인들을 위해 대포밥 노릇을 하고 있었다. 어쩌면 그것은 맞는 말이었다. 한국인들이 스스로 전쟁을 시작했다는 건 사실이었다. 하지만 그들처럼 작은 나라는 힘이 더 센 나라들을 위한 전쟁터가 될 수밖에 없었다. 이 전쟁에서 누가 이기든 한국은 패자일 게 분명했다.

본국 송환 거부자들은 미군이 그들을 본국으로 보내버릴지 모른다고 생각하기까지 했다. 그들의 두려움은 허무맹랑한 것이 아니었다. 판문점 회담에서는 무슨 일이든 생길 수 있었다. 미국은 그들을 본국으로 송환함으로써 얻을 것이 충분하다고 생각되면 어느 때라도 그들을 중국에 넘길 수 있었다. 1만 4천 명의 죄수들은 그 가능성을 생각하고 질겁했다. 공산주의자들에게 보복당할 게 두려워, 일부는 그들을 강제로 배에 태우면 바다에서 빠져 죽을 작정이었다. 일부는 최악의 상태가 되면 감옥을 부수고 한라산으로 들어가 게릴라 생활을 하겠다는 생각까지 했다. 많은 사람들이 창과 칼과 몽둥이를 만들기 시작했다. 실제로 처음 몇 달간 그들의 포로 생활은 바닥이었다. 여러 사람들이 자살을 시도했다. 한 사람은 죽으려고 변소에 뛰어들었다가 동료들에 의해 구조되었다. 그들은 그를 보살펴줬다. 그는 반년 후에야 우울증에서 벗어났다. 지아푸가 미친 것은 그 무렵이었다. 하지만 여느 사람들과 달리 그는 정신이 다시 돌아오지 않았다.

나는 속으로는 공산주의 정부가 옛 정권보다 책임의식이 강하다고 생각했다. 일반 시민들을 위해서는 몇 가지 좋은 일을 했고, 중국을 더 강한 나라로 만든 건 사실이었다. 하지만 동시에 나는 공산주의자들이 두려웠다. 사람들의 목숨과 마음을 통제하는 그들의 방식이 두려웠다.

그런데 이곳에서는 나에게 더 괴로운 다른 종류의 정치 교육이 있었다. 그것은 자기비판과 상호비판이었다. 우리에게는 어떤 식으로든 우리가 적군을 도왔다는 걸 인정하고, 고의든 아니든 우리가 저지른 범죄를 고백하라는 명령이 내려졌다. 우리는 모두 인민해방군에서 근무했던 사람들이었다. 때문에 많은 사람들이 자신의 과거에 대해 형식적으로만 얘기했다. 아무도 그들에게 고백하라고 강요하지 않았다. 하지만 나는 예외였다. 거의 1년 동안 공산주의자들의 수용소에 있었기 때문이었다. (중략)

나는 기가 질렸다. 수많은 생각이 내 머릿속을 감돌았다. 당신네들과 공산주의자들의 차이가 무엇인가? 나는 이 세상 어디에서 진정한 동지들 속에 있을 수 있을까? 왜 나는 늘 혼자일까? 나는 언제쯤 어딘가에서 편안함을 느낄 수 있을까?

나는 혼자 있을 때마다 중국으로 어떻게 돌아갈 것인지를 생각했다. 나는 국민당 군대가 공산주의자들을 무너뜨리고 본토를 다시 장악할 수 있다고는 생각하지 않았다. 그들은 미국제 무기로 무장하고 처음에는 동원인력도 더 많았지만, 사람들의 지지를 끌어낸 공산주의자들한테는 적수가 되지 못했다. 붉은 깃발은 어쩌면 가까운 미래에 타이완에서 휘날릴지 몰랐다.

나는 선물이 좋긴 했지만 국민당을 잘 알기 때문에 정신을 차리려고 노력했다. 솔직히 말해 그들은 군대를 위해 사람을 필요로 하고 있었다. 그에 반해 공산주의자들에게는 수백만 명의 병력이 있었고, 동원 가능한 인력도 세계에서 가장 많았다. 그것이 양쪽으로 하여금 전쟁포로들을 달리 취급하게 만들었다. 어쩌면 국민당 애호자들로 하여금 전쟁포로들을 훨씬 더 소중히 하도록 강요한 것은 그들이 처해 있던 절망적인 난국이었을 것이다.

붙임

역자 후기를 통해 역자가 이 책의 번역에 대단히 신경썼을 거라는 사실을 짐작할 수 있다. 왕은철 교수는 하진의 다른 책도번역했을 만큼 하진의 글에 애착을 갖고 있는 것 같다. 그럼에도 불구하고 이 책이 영어로 쓰여졌고, 지명과 인명을 중국어의 영어표기로 된 것을 다시 한국어로 옮기느라 발생한 작은 오류들에 아주 사소한 아쉬움이 느껴진다. 일단 압록강을 얄루쟝이라고 표기한것이나 (이것은 작가가 초반에 압록강이라고 한자 주석을 달아 뒀다. 그래서 어쩌면 일부러 그런 걸 수도 있겠다는 생각이 들지만,어쨌든 이 책에는 일러두기도 없으므로 알 수 없는 일이다.) , 중간에 등장하는 장페이나 리쿠이 등은 장비나 이규를 뜻하는것임에 틀림없다. 만추리아는 만주의 영어명인데, 만주를 쓰거나 아예 만저우를 썼어야 하지 않았을까? 유안, 펭얀 등의 현대 인명역시 yuan, peng yan을 옮긴 게 아닌가 하는데, 역자가 중국어 병음 표기법을 모른다면 어쩔 수 없지만 조금 아쉬운부분. 하지만 이런 것들은 중국과 관련된 영미서적을 옮길 때 흔히 있는 일이므로 역자가 소홀했다고 보기엔 어려울 수도 있겠다.그저 조금 아쉬울 뿐.

한편 초반에 '한국인 포로'이라는 표현이 자주 등장하는데, 북한군 포로를 뜻하는 걸 거라고 추측은 했지만그럼에도 조금 혼란스럽게 느껴졌다. 작가가 아마 그냥 Korean이라고 쓴 것을 번역한 거겠지만 그러려면 한국인이 아니라 조선인이라고 번역해야 하지 않을까? (물론 이를 통해 당시는'Korea'가 남북한을 아우르는 개념이었겠구나 하는 너무나 당연한 깨달음을 얻었다. 지금은 마치 Korean이 남한인만을 일컫는 것처럼 인식하고 있지 않던가? 갑자기 Korean이 북조선인일 수도 있다는 사실을 깨달으면 어쩐지 새로운. '우리'의 폭이 좁아진 것 같다. 나만 그런가?), 후반에는 또 북한과 남한이라는 구분이 등장하는데, 그런데 북한이라는 표현은 정작 북한에서는 북조선이라고 하니까. 물론 아주 사소한 것이지만 약간 신경이 쓰였다. 주석을 달거나 일러두기를 통해 기준을 명시했더라면 훨씬 좋았을 것 같다. 물론 전체적인 번역은 아주 깔끔해서 몰두해서 읽는 데에 전혀 문제가 없었다.

밸리 : 도서 2008/10/18 16:20

태그 : 하진, 전쟁쓰레기

-----------------

덧글

Moon 2008/10/18 18:15 # 답글

Moon 2008/10/18 18:15 # 답글

저는 北島 도 좋더라고요. 현당대 쪽에서 많이 다루는 작가(주로 시를 써요)인데 전 요새 그가 얼마전에 출판한 靑灯 이라는 산문집을 읽고 있어요. '역시 北島!' 란 느낌과 더불어 꽤나 가볍기도 해서 괜찮아요, 살짝 추천이요.

sebin 2008/10/18 19:51 #

sebin 2008/10/18 19:51 #

처음 듣는 작가인데 기회가 되면 꼭 읽어볼게요. 시쪽은 잘 모르지만 산문은 좋아해요. 고맙습니다. :)

페스츄리 2008/10/18 19:37 # 답글

페스츄리 2008/10/18 19:37 # 답글

아..저도 이 책 읽고 독후감 하나 쓸려고 했는데..--;;;; 너무 훌륭한 서평을 쓰셔서, 제가 이 책을 읽는데 많은 도움이 될 것 같습니다. 오..전 지금 유안이 압록강변을 갓 넘어서 북한땅을 밟는 장면까지 읽었습니다.

sebin 2008/10/18 19:53 #

sebin 2008/10/18 19:53 #

서평이라고 말하기엔 너무나도 부족하고, 그냥 찝어둔 부분들을 그대로 올려둔 것에 불과한걸요. 재미있는 책이라 순식간에 읽게 되네요. 페스츄리님의 감상도 기대할게요.

페스츄리 2008/10/18 20:03 # 답글

페스츄리 2008/10/18 20:03 # 답글

하진 책은 다 사다 읽어봐야 할 것 같아요.^^ 광인이나 기다림 등등..위화와는 달리 이 작가는 중국 현대사를 "정면돌파"하는 것 같아서 좋습니다. 이 작가가 다루는 내용들이 심상치 않은 것 같아요. 하긴..위화와는 주변환경이 달라서 그런지도 모르지요.(미국에서 살고 있는 중국인 작가와 중국대륙내에서 작품활동을 해야 하는 작가를 일괄 비교하는 것이 말이 않되는 거지요) 위화의 글을 보면 적어도 중국 현대사에 대한 "우회적" 비판 아니면 "모른체하기"가 눈에 자주 띔니다. (예를 들어서..인생같은 경우에 푸구이의 인생을 망쳐놓는데 결정적인 역할을 했던 중국사회 더 나아가 공산당 체제에 대한 비판이 전혀 없죠. 완전 개인사 서술에 만족하죠. 하긴 거기서 더 나아갔다면 위화는 끌려갔을 가능성이 상당히 크고.. 아니면 리저허우처럼 망명을 하든지..허삼관 매혈기도 마찬가지입니다. 물론 그 자체가 비판이라면 비판이지만 그런 정도의 비판은 문학의 사회적 기능을 생각할 때..크게 의미가 반감된 비판입니다)

그렇다고 해서 하진의 소설이 다이호우잉같은 사람들이 보여주는 "상흔문학"과도 동렬에 놓기도 그런 것 같네요. 하진에게는 그런 센티멘털리즘은 없는 것 같거든요.(내용을 한번 죽 읽어보고 드리는 말씀) 오히려 최인훈의 "광장"에 보이는 치열함이 눈에 자주 띄입니다.

sebin 2008/10/18 20:14 #

sebin 2008/10/18 20:14 #

그쵸, 역자도 뒤에서 이야기하지만 저도 최인훈의 광장 생각을 했어요. 중간에 중립국 얘기도 나오고.. 아마 한국인이라면 다들 한번쯤은 광장을 떠올리게 될 것 같아요, 그래서 한국인에게 더욱 특별한 작품이 아닐까. 저도 다음에 한국에 나가서 하진의 책들을 좀 더 사서 볼까 하고 있습니다. 기다림도 평이 참 좋은 것 같더라구요. 서평을 먼저 보면 책을 볼 때 서평에 휩쓸릴까 자제하고 있긴 하지만...

위화는 60년생, 하진은 56년생이니까 조금 다르지 않을까 해요. 4년차이지만 하진은 문혁의 광풍을 직접 겪은 세대겠죠.. 위화는 그때 아직 어렸겠고, 추측하지만 환경도 하진보다 좋았던 듯 하죠. 위화는 어린 시절 책을 많이 읽을 수 있었다고 했으니까.

페스츄리 2008/10/18 20:07 # 답글

페스츄리 2008/10/18 20:07 # 답글

"인민을 위해 복무하라"---옌렌커의 작품이던가요? 이 책 서점에서 훑어보고..이 책도 좀 충격받았습니다. 내용이 정말 "마오이즘"을 "희화화"한다는 생각이 딱 들더군요. 이 책도 구입 1순위입니다.^^

백면서생 2008/10/19 14:29 # 답글

백면서생 2008/10/19 14:29 # 답글

잘 읽었습니다.

-----

1.

[국내도서] 기다림

하 진 (지은이), 김연수 (옮긴이) | 시공사 | 2007년 8월

(53) | 세일즈포인트 : 855

(53) | 세일즈포인트 : 8552.

[국내도서] 멋진 추락

하 진 (지은이), 왕은철 (옮긴이) | 시공사 | 2011년 1월

(20) | 세일즈포인트 : 486

(20) | 세일즈포인트 : 486

[국내도서] 전쟁 쓰레기

하 진 (지은이), 왕은철 (옮긴이) | 시공사 | 2008년 7월

(4) | 세일즈포인트 : 466

(4) | 세일즈포인트 : 466

[국내도서] 니하오 미스터 빈

하 진 (지은이), 왕은철 (옮긴이) | 현대문학 | 2007년 5월

(9) | 세일즈포인트 : 251

(9) | 세일즈포인트 : 251

[국내도서] 남편 고르기

하 진 (지은이), 왕은철 (옮긴이) | 현대문학 | 2006년 11월

9,000원 → 8,100원 (10%할인), 마일리지 450원 (5% 적립)

(5) | 세일즈포인트 : 155

(5) | 세일즈포인트 : 155

---

War Trash

Ha Jin

$8.24 (USD)

Publisher: Thorndike Press

Release date: 2005

Format: EPUB

Size: 0.36 MB

Language: English

Pages:

No comments:

Post a Comment