Why Does Korea Have so Many of Those Damn Smutty Ads? – The Grand Narrative

Why Does Korea Have so Many of Those Damn Smutty Ads?

The Grand Narrative Censorship, Gender Roles, Gender Socialization, Korean Advertisements, Korean Economy, Korean Media, Korean Sexuality, Sexual Harassment March 18, 2019

Government inaction on Korea’s ubiquitous, sexually-explicit internet advertising undermines claims that its citizens need protecting from pornography, and has helped shape the Korean #Metoo movement.

Estimated reading time: 17 minutes. Photo by rawpixel.com from Pexels. One NSFW image later.

Estimated reading time: 17 minutes. Photo by rawpixel.com from Pexels. One NSFW image later.When even the ad industry itself is calling for greater government regulation of sexual imagery in ads, you know Korea’s got a problem.

The main issue is that there’s just no escaping them. In the most recent survey of 155 major web portals, social media services, and online news sites conducted by the Korea Internet Advertising Foundation (KIAF) in 2016, 94.5 percent of the middle and high school students surveyed were found to have been exposed to sexualized ads. Frustratingly, the 69-page report (PDF, Korean) doesn’t also mention what proportion those ads were of the total ads examined. But, maybe the authors simply felt that was unnecessary, as everyone already knows that their numbers are just insane:

Raphael Rashid@koryodynasty

Porn remains illegal in Korea. And just last week, the government cracked down on loopholes to make the viewing of porn even more difficult.

Meanwhile, these ads objectifying women as sex objects flood the internet, appear on almost all 'respectable' Korean news sites, and more

479

4:36 PM - Feb 17, 2019

2,265 people are talking about this

Twitter Ads info and privacy

See the thread for many more examples. Or like Raphael says, almost any Korean news website. Even alongside the cutesy, assumed safe webtoons my preteen daughters read too, I recently learned, sometimes there’s invitations to meet horny divorcees in our area.

But Korea’s smutty ads problem goes much deeper than just their scale, or their astonishing inappropriateness. For the KIAF surveyors also found that one in four of the offending ads promoted sex work, and/or even showed sex acts. Which is heinous not because either are unethical, but because such ads exist so brazenly in a society where sex work and pornography are both illegal, and which would never see the light of day in traditional media.

Which begs the question: just how did Korea’s internet ad problem get so bad?

In the first instance, it’s simply down to advertisers’ algorithms, combined with the inattention and unconcern of site owners. This was ironically and hilariously revealed by the reporting of a similar survey by the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family (MOGEF) in June 2012, when many news sites displaying precisely the kinds of ads the Ministry was railing against alongside the articles about the survey. Even more spectacularly, a few weeks previously many news site editors curiously chose to pixelate the bikini tops and bras of women who had written political messages across their breasts (as in only their clothing, not the messages or exposed skin), while those in the accompanying ads were left untouched:

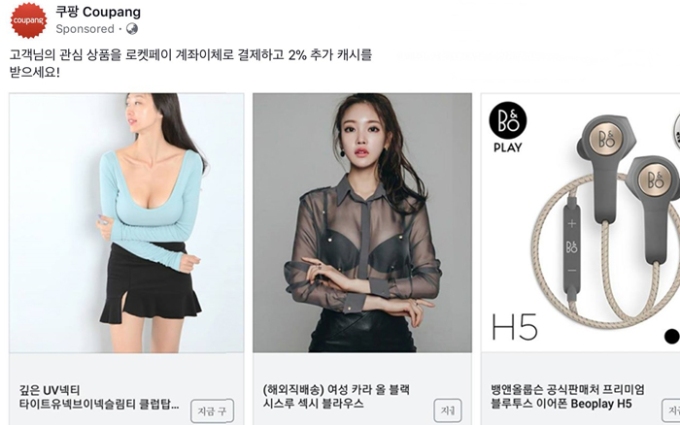

Fast forward to April 2018, when representatives from major Korean shopping portal sites were queried by The PR Newsreporter An Seon-hye as to why their Facebook ads for products such as headphones and men’s shoes tended to show women with exposed cleavage and/or in their underwear first. They simply blamed the algorithms, implying that somehow those absolved their companies of any responsibility:

Fast forward to April 2018, when representatives from major Korean shopping portal sites were queried by The PR Newsreporter An Seon-hye as to why their Facebook ads for products such as headphones and men’s shoes tended to show women with exposed cleavage and/or in their underwear first. They simply blamed the algorithms, implying that somehow those absolved their companies of any responsibility: 페이스북에서 남성 이용자들에게 노출된 쿠팡 광고 이미지 “Coupang advertisement aimed at male users of Facebook.” Image source: The PR News.

페이스북에서 남성 이용자들에게 노출된 쿠팡 광고 이미지 “Coupang advertisement aimed at male users of Facebook.” Image source: The PR News. 티몬(왼쪽) 및 gs샵이 sns에서 남성들에게 집행한 광고 이미지. “Images of Timon(L) and GS Shop advertisements aimed at men.” The woman on the right is Ai Shinozaki, a Japanese gravure model. Image source: The PR News.

티몬(왼쪽) 및 gs샵이 sns에서 남성들에게 집행한 광고 이미지. “Images of Timon(L) and GS Shop advertisements aimed at men.” The woman on the right is Ai Shinozaki, a Japanese gravure model. Image source: The PR News.…하지만 해당 업체들은 결코 고의성이 없다는 점을 강조했다. 티몬 관계자는 “저희 같은 경우 19금 용품 광고는 아예 노출이 안 되도록 막는 등 선정성 측면에서 신경을 쓰고 있다”며 “자동 로직으로 광고 집행이 이뤄지기에 임의로 자극적 이미지를 사용한 게 아니다”고 해명했다.

“…However, industry representatives stressed that, in the end, there is never any deliberate intention to use sexualized imagery. A representative from Timon said, ‘In our case, from the outset we do work to ensure that no adults-only products are selected to be advertised [on Facebook],’ and that ‘the provocative images that do appear are not random, but are chosen automatically by the algorithm.'”

기본적으로 특정 시간대에 특정 연령 타깃군이 어떤 상품을 많이 봤다는 데이터가 쌓이면 이를 해당 타깃에게 동일하게 추천하는 방식으로 로직이 짜여 있다는 설명이다. 이번 노출도 이같은 설정 때문에 벌어진 현상일 수는 있지만, 의도한 건 아니라는 설명이다.

“Basically, when collected data on a site suggests that a certain time is the most heavily frequented by a targeted demographic, the algorithm automatically recommends products that demographic is likely to be interested in. The same logic applies to the revealing images accompanying them, but has never been the deliberate intention [of our company.]”

쿠팡 관계자 역시 “쿠팡이 고의적으로 선정적인 광고를 남성에게 보이도록 조작하지는 않았다”며 “활용되는 이미지 역시 판매자가 올린 것을 활용한 것”이라고 밝혔다.

“A representative from Coupang also claimed that their company ‘did not deliberately manipulate ads to target men with sexualized imagery,’ explaining that ‘the images of products [available from our site] are simply taken from available sellers.’ (end)

By all means, gratuitous T&A does sometimes work, especially when those objects belong to popular K-pop girl-group members. Yet it infuriates me when some, more radical feminists—especially anti-pornography activists—start from the position that such narrow portrayals of women are an accurate reflection of most—or even a significant minority of—cishet men’s tastes; examples like these demonstrate just how disingenuous and utterly unfair that assumption is. It’s also very patronizing for companies to advertise this way, says Sejong University Professor Kim Ji-heon elsewhere in the above article, and has the potential to put men off offending brands. Accordingly, evidence of sexualization’s effectiveness on Korean consumers is mixed, one 2017 study by Yonsei University researchers (PDF, Korean) for example, discovering that young Korean men actually preferred cute to sexy female models in game advertisements (which may be problematic for other reasons, but that’s a story for another post). Also, lest we forget, not all consumers are young men, with another study from 2012(PDF, Korean) by Sungkyunkwan University researchers demonstrating that despite soju companies specifically targetingfemale consumers at the time, somehow women just weren’t responding to the ensuing “sexy” advertisements.

I can’t imagine why:

Screenshots from this summer 2009 commercial for ‘Cool Soju 168’; the logic was that “168” referred to a low 16.8% alcohol content, which supposedly helped women maintain their figure vis-a-vis stronger brands. One NSFW image follows shortly.

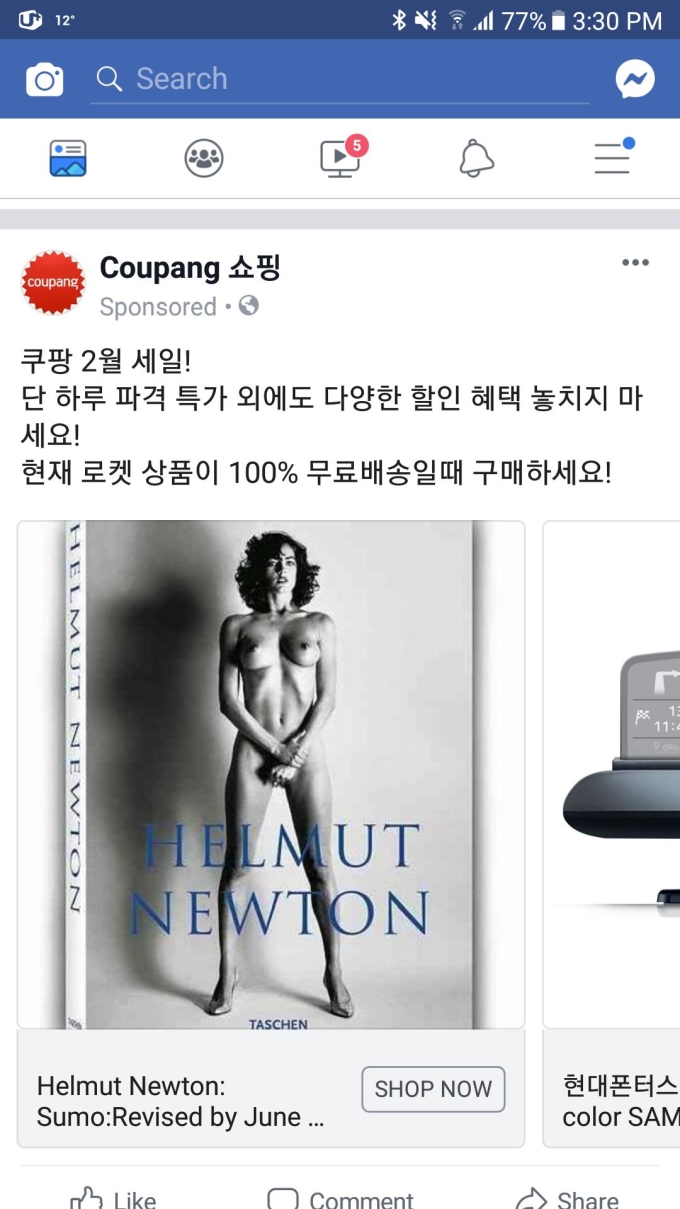

Screenshots from this summer 2009 commercial for ‘Cool Soju 168’; the logic was that “168” referred to a low 16.8% alcohol content, which supposedly helped women maintain their figure vis-a-vis stronger brands. One NSFW image follows shortly.Nevertheless, Coupang’s algorithms at least, have hardly been tweaked since The PR News report came out, as any male Facebook user in Korea can confirm. Take this advertisement I was blessed with on the subway a few weeks ago for instance:

Facebook has given me 24 hour bans for far less.

Of course, in reality, no algorithms are value-neutral, so can’t be used as an excuse. Yet, to reluctantly play Devil’s Advocate for a moment, perhaps one reason Korea’s algorithms have the settings they do is that advertisers generally lean more heavily on sex-sells tropes during recessions, and one indication of how bad Korea’s is at the moment would be its highest youth unemployment rate in two decades. Another explanation of why they tend to be sooo eye-catching is that Hangul, the writing system, lacks capitals. This, which has factored into Korean webdesign from the get-go, is why Korean websites tend to be so GIF-heavy and cluttered to Western eyes, but is familiar to and preferred by Koreans. (Japanese websites are very similar, due to similar issues with kanji and kana.) Ingrained media culture and consumer habits go some way toward explaining why Japanese and Korean advertisers over-rely on celebrities to get your attention too.

But all of these contributing factors are decades old. I first noted the alleged link to the economy ten years ago, and the numbers of smutty ads have only increased since. Korean websites have overwhelmed me with GIFs since I first started having to navigate them in internet cafes here nineteen years ago. And the over-reliance on celebrities dates back to the early-1980s, when fifteen seconds became the standard length for TV commercials.

If so many features of Korean advertising are products of ingrained culture and long-term habit then, surely this over-reliance on sexualization could be as well? So too, that it just so happens to be a very stereotypically male-gazey version of it at that?

Noteworthy in this regard is men’s domination of multiple sectors of the Korean media:

Raphael Rashid@koryodynasty

Men dominate media in Korea:

- KBS: 9 of 11 board members male

- MBC: all 9 directors were male, 2 women appointed recently

- EBS: all 9 directors were male, 4 women appointed recently

according to survey by National Human Rights Commission of Koreahttps://www.humanrights.go.kr/site/program/board/basicboard/view?boardtypeid=24&boardid=7603755&menuid=001004002001 …

13

11:23 PM - Feb 7, 2019

Twitter Ads info and privacy

29 people are talking about this

However, the Korean advertising industry is absent from that Twitter thread, and I’m personally unaware of its male-female make-up as I type this (sorry). So, let me defer to someone with inside experience: Seoul National University Associate Professor Olga Fedorenko, who conducted fieldwork in winter 2009-2010at the agency responsible for the delightful Cool Soju 168 commercial from summer 2009 above. And in fact, in that agency at least, women made up roughly half of the employees. But it was indeed male-dominated, as no women there were above level five of the eight ranks within its internal hierarchy, “with truly managerial responsibilities [only] beginning at level six.” Also, the ensuing work-culture there could certainly be described as male-dominated too:

To assert that “sex sells”—the axiom that no one doubts in advertising and perhaps few do in society at large—was the usual way to deflect my criticisms of sexualized portrayals of women in much of Korean advertising, and women repeated that adage as eagerly as men.

Still, despite their professional embrace of the “sex code,” women showed a certain distance towards its centrality to advertising. They occasionally mocked male managers who favored sex-appeal strategies by default, “just because they like to look at pretty women,” as Chin’a put it, as she vented about wasting an afternoon the day before because her team’s Creative Director asked her to accompany him to help pick a female model for a commercial. “He said he wanted a woman’s opinion but in reality he just picked the model who he personally liked and who was flirty with him,” she said rolling her eyes in front of me and four other women as we were having lunch. Chin’a thought that the selected model was not the best choice, but the Creative Director never asked Chin’a’s opinion and even went as far as to re-schedule the shoot around the model, without consulting the convenience of other team members. Chin’a wished she had spent that afternoon working on their team’s other accounts.

Technically however, Fedorenko does not state if the same agency was responsible for the Cool soju commercial I criticized; I should have only said it “probably” was, because it was responsible for a new campaign for same product during Fedorenko’s time there a few months later. Ironically, a largely women-created and targeted, sexually-progressive, feminist, and therefore controversial one:

Which would seem to contradict the points made about work culture above. So too, that they’re from a snapshot of just one agency, and a decade old.

However, it’s also telling that there’s been almost nothing quite like that campaign in Korean advertising since, by any agency. Despite my fetish for Korean ads showing actual grown women with sexual desire and experience, I’m only aware of less than a handful produced in the last decade. Meanwhile, compared to men, women are almost 60 times more likely to be wearing revealing clothing in Korean TV commercials, a figure that is over twice as high and nearly ten times as high as their Japanese and Hong Kong counterparts respectively.

And yet, despite everything, I’m reluctant to attribute all that simply to the likely dominance of men in the industry.

Yes, we can all bet good money that the coders behind offensive internet algorithms are indeed sexist pricks. Or their bosses. Or at best, that they’re unoriginal and conservative.

But to claim that Korean ads are the way they are because men dominate the industry, is to make the assumption that most of the men within are also sexist pricks.

Hey, I’m not dismissing the possibility. In fact, I’d bet good money on that too. Given what we know about Korean ads, and that Korea has the biggest gender gap in the OECD, and comes 121st out of 193 countries in the ratio of female legislators to males, then there’s absolutely no reason to suppose that Korea’s toxic, patriarchal work culture hasn’t also infected the Korean ad industry.

But where does that accusation get us? If we want to persuade industry insiders to embrace change, what good would simply calling them sexist pricks actually achieve?

And cishet men’s sexuality, I can’t stress often enough, is so much richer and broader than its blokey, infantile stereotypes suggest. There are men of other sexualities in the ad industry too, not to mention (probably) equal numbers of women. I refuse to believe that all the admen, by definition among the most creative and artistic men in Korean society, all chose their careers based on no more than a shared dream of putting more boobs on phone screens, and that every man and woman who doesn’t share that grand vision is simply forced to acquiesce.

The issues raised in this post may even be well-recognized problems within the industry already too, but are intractable due to the influence of Korea’s patriarchal work culture as alluded to earlier, one big influence being the rigid hierarchyand visions of women and male-female relations learned before entering the industry from that vast socialization experience known as universal male conscription.

Or not: my apologies again, for lacking the money and time to translate dense Korean advertising tomes to find out. But either way, suggesting practical, actionable steps that the industry may already be receptive to does sound much more helpful than simply rolling our eyes at THE MENZ.

I think this is where we came in.

Recall that we started with the industry itself calling for more regulation. Specifically, the KIAF, responsible for the 2016 survey:

“Although there are guidelines for the level of sexuality permitted in online advertising, they lack effectiveness since they tend to be too generic and ambiguous,” said the KIAF official. “Regulations that manage such advertisements are scattered across government departments, and they need to be revamped.

A state of affairs which sounds suspiciously similar to the messy censorship of K-pop in the early-2010s:

The recent guidelines by the Fair Trade Commission are demonstrably inadequate, and laws are required instead. But considering that any limits on such a vague concept as sexualization are by definition arbitrary, then it is crucial that 1) the ensuing legislation process is transparent; 2) that implementation of the laws is consistent; and 3) that only one, preferably independent, organization has the power of censorship. Currently, that last is divided between a plethora of competing media and government organizations, and the ensuing unpredictable and often bizarre decisions ― including banning a music video for the singers driving without wearing seat belts, or allowing exposed navels on men but not on women ― have thoroughly undermined the credibility of attempts to curb the sexualization of teens in K-pop. A fresh start is urgently needed.

“Restrictions Imposed on 18+ Controversial ‘Wide Leg Spread Dance’”, April 2011. Source.

“Restrictions Imposed on 18+ Controversial ‘Wide Leg Spread Dance’”, April 2011. Source.This segue into K-pop is no mere confirmation bias from a trusted source: for the body with the most responsibility for censoring K-pop then was MOGEF, which it did with a relish. As Lee Yoo-eun at Global Voices explained in 2014 (links added by me):

The censors of the ministry are notorious for accusing several thousand songs of being “hazardous” whenever they notice references to liquor, cigarettes or sex in the lyrics. Once a song is labeled as “inappropriate for youth under the age 19″ it can only be broadcast after 10:00 PM, and children are forbidden from buying it as well as from listening on the internet. Many young people get around this by using the IDs of their parents to login to Korean portal websites or watch on YouTube.

Music industry people…say it is troubling that the censorship is applied only to some randomly selected albums after they have hit the market, and not universally to every album. Many people see this as part of a new reality where the South Korean government is tightening control over citizens and free speech.

And this zealousness was in stark contrast to the complete inaction by MOGEF over smutty advertisements, despite raising the alarm in 2012 about their surging numbers as discussed. Indeed, it wanted the industry to do its own work for it instead:

여성가족부는 작년과 비교해 유해 광고는 늘었지만 법 위반 언론사들이 대폭 감소한 것을 감안해, 언론사에는 우선 자율 규제를 촉구하겠다는 입장이다. 청소년매체환경과 관계자는 “작년에 34개 언론사가 법을 위반했는데 올해에는 다 시정됐다”며 “언론사들을 직접 규제하기 보다는 인터넷신문협회 등에 자율규제기구인 인터넷신문광고심의위원회의 설치를 촉구하겠다”고 밝혔다.

“Although MOGEF points out that the numbers of harmful advertisements have increased since last year, the fact that there are actually less media companies breaking the law also needs to be taken into consideration, so first MOGEF is going ask media companies to regulate themselves. The official in the Division of Youth Media Environment continued: ‘The 34 media companies that broke the the Information and Communications Network Law last year have all since rectified their mistakes,’ and so ‘a self-regulatory system is preferable to direct regulation, and we demand that the Korean Internet Newspaper Association and so on establish an internet newspaper advertisement consideration committee.'” (end)

Further inaction still is evident from how, in the 2010-2016 period, MOGEF’s Korean Institute for Gender Equality Promotion and Education (KIGEPE) was given the task of monitoring mass media for cases of sexual discrimination, sexual prejudice, and sexual insults, but was given extremely limited resources to do so, and didn’t even cover the internet; ultimately only four cases were ever acted upon in those entire seven years. A subsequent study in 2016 found an undisclosed number of issues, of which the KIGEPE said “the results from their monitoring [had] resulted in 19 cases of corrective action [as of March 2017], insisting more education and appropriate measures need to be provided for TV show makers to achieve gender equality in the TV industry.” (More recently, this January the Korea Communications Standards Commission {KOSC} noted problems remained in variety shows specifically, without suggesting any measures to combat them.)

Yet that’s just MOGEF, which—without absolving it for its inaction—admittedly had very low resources and was in a precarious political position under previous conservative governments. If we look at the Korean media and its various overseers as a whole however, inaction over misogyny and problematic content is endemic, Korean dramas in particular being notorious for depicting dating violence as romance, but which the KOSC has washed their hands of. And don’t get me started on the media’s constant framing of the sexualization of minors in K-pop as good, clean, harmless family fun.

Source: Netizenbuzz.

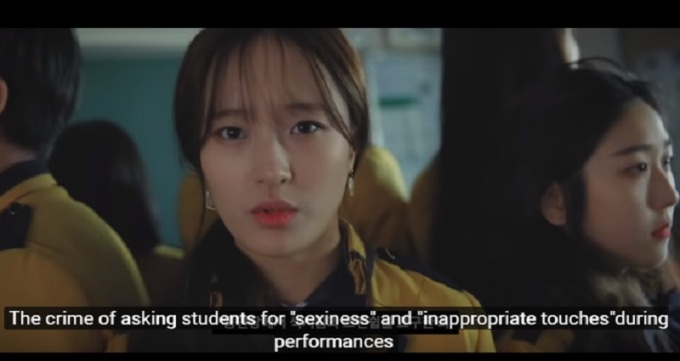

Source: Netizenbuzz.In that wider context, inaction on smutty ads emerges as less the exception than the rule in the Korean media, and underpins a pervasive culture of indifference and desensitization towards degrading images and videos of (overwhemingly) women. That culture is evident in the decade-long foot-dragging in the shutting-down of Soranet, a hugely popular pornography site notorious for the sharing of hidden camera videos, as well as in the Korean #MeToo movement’s unique emphasis on punishingthe purveyors of such videos, a central component in the current Burning Sun scandal. I can’t help but ultimately see links to the culture of indifference and desensitization towards sexual abuse by teachers in Korean schools too, with over 40 percent of perpetrators in the January 2013 to September 2018 period still teaching, and again only, finally, being aggressively challenged due to the Korean #MeToo movement.

Nextshark: “The School of Performing Arts Seoul, the alma mater of numerous well-known K-drama and K-pop stars, is facing controversy after its former students accused the school of corruption and sexual exploitation of minors [through a music video].”

Nextshark: “The School of Performing Arts Seoul, the alma mater of numerous well-known K-drama and K-pop stars, is facing controversy after its former students accused the school of corruption and sexual exploitation of minors [through a music video].”But perhaps it’s a too much of leap from boobs on my smartphone to tolerating “asking students for ‘sexiness’ and ‘inappropriate touches’ during school performances”?

Or not. Either way, if the government started to enforce the same standards for internet ads as it does for all other forms of pop culture, that would surely be the perfect way to find out.

Related Posts:

Korean Media Misogyny: Not worth monitoring?

“Harmful” Advertisements Surge 3-fold in Online Korean News Media

Expect More Nudity During This Recession

Why Korea Has so Many Celebrity Endorsements, and Why That’s so Important for Understanding Korean Pop-Culture

“I am a Woman Who Buys Condoms.”

“Girl-groups in Hot Pants” Isn’t a Concept That Always Sells a Product. Except When it Does. Damn.

#MeToo to meat: no more soju calendars with nearly nude women in South Korea

If you reside in South Korea, you can donate via wire transfer: Turnbull James Edward (Kookmin Bank/국민은행, 563401-01-214324)

Share this:

80Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)80

Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Click to share on Skype (Opens in new window)

Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

Click to print (Opens in new window)

Click to email this to a friend (Opens in new window)

More

Related

Korean Gender Reader

In "Korean Gender Reader"

Countering Sexual Violence in Korea (Updated)

In "Busan"

Korean Sociological Image #18: Sexualizing Caucasian Women

In "Body Image"

Tagged

여성가족부

MOGEF

Post navigation

Previous Post Hyundai Fit-Shaming Korean Girls

Next PostToday I Read About an Awesome Feminist Japanese Painter and Was Reminded Of My Favorite Soju Poster

3 thoughts on “Why Does Korea Have so Many of Those Damn Smutty Ads?”

March 23, 2019 at 1:43 am

Thanks for the write-up! I’ve been shocked before, primarily by how out of context and unnecessary they seem, by the graphic ads when visiting Korean websites, and it’s gratifying to see you give it the Grand Narrative treatment. Please keep it up!

Reply

March 24, 2019 at 3:42 pm

Nice to know these long posts are still read and appreciated thanks :)

TBH though, I’ll soon be making some big changes to the length and frequency of posts, for reasons which I’ll explain later. But rest assured I’ll still be applying “the Grand Narrative treatment” (ㅋㅋㅋ) every now and then. Partially, because I just can’t help myself, but also partially because of feedback like yours. So thanks again!

Reply

No comments:

Post a Comment