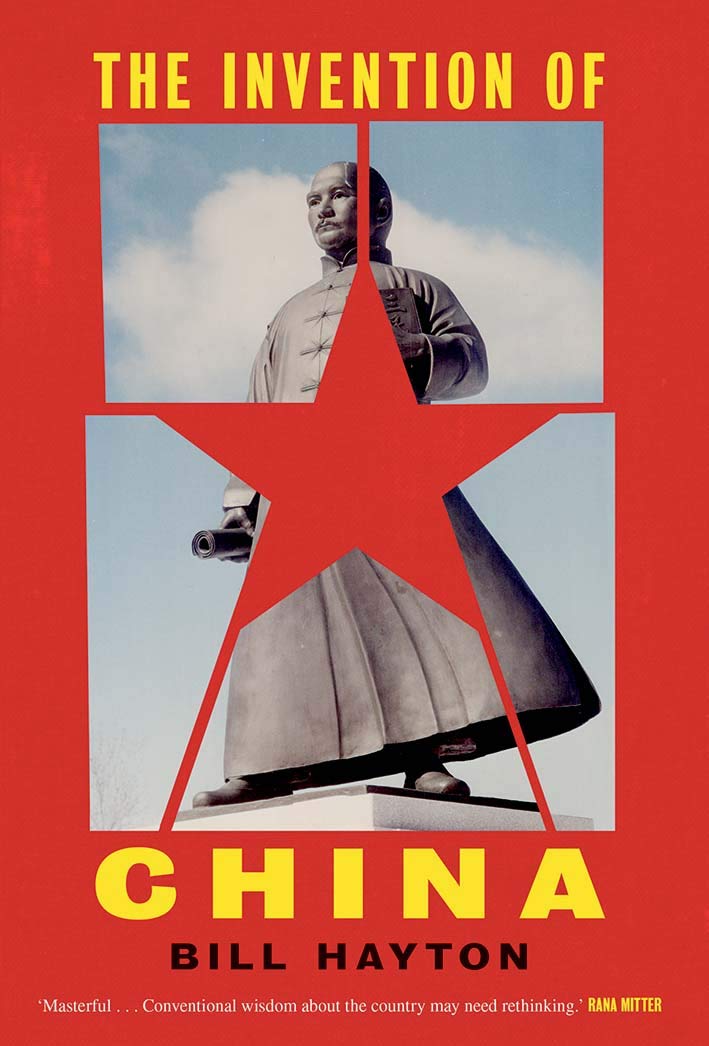

The invention of China / Bill Hayton.

Summary:

China's current leadership lays claim to a 5,000-year-old civilization, but "China" as a unified country and people, Bill Hayton argues, was created far more recently by a small group of intellectuals. In this compelling account, Hayton shows how China's present-day geopolitical problems -- the fates of Hong Kong, Taiwan, Tibet, Xinjiang, and the South China Sea -- were born in the struggle to create a modern nation-state.

Author:

Hayton, Bill, author.

Physical Description:

xi, 290 pages, 12 unnumbered pages of plates : illustrations (some colour), maps, portraits (some colour) ; 20 cm.

Publication Date:

2020

Book Review: The Invention of China

According to Bill Hayton, the modern Chinese state was constructed, or “invented,” at the end of the Qing Dynasty, based on Western ideas of nation, race, history, and territory. In The Invention of China, Hayton demonstrates that China is no more ancient, special, or authentic than most other states.

Today, there is a widely accepted view that China is a unique 5,000-year-old civilisation. It is represented in countless narratives as a unified country on a single piece of territory, with a single culture, dominated by the Han race, speaking a single language, Putonghua. In short, it is revered as “a civilisational state.” The strength of this belief silences historical timelines of Chinese colonisation by the Manchus (Qing Dynasty) and the Mongols (Yuan Dynasty). But the Chinese culture is so sophisticated and powerful that these invaders were sinicized and became Chinese.

Much of this view of China’s history and civilisation is a modern construction, or “invention,” according to Bill Hayton in his recent book, The Invention of China. Throughout history, no state ever called itself China. Rather, dynasties used terms like “The Qing Great State” and the “Ming Great State.” Before the 20th century, “China” was a term used only by Westerners, like travellers, traders, and missionaries. And no one spoke of a Han race before 1900.

Moreover, the Qing Great State was not even a Chinese empire. It was led by Manchus, who came from Manchuria in the north east, outside the Great Wall, after they invaded the Ming empire in 1644. The former Ming “China” thus became a colony of a Manchurian empire, which also colonised Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Tibet. These regions had rarely been affiliated with China, and were not part of the Ming Dynasty. In sum, there were five different parts of this inner Asian empire.

To be sure, there were people living in the current Chinese territory 5,000 years ago and many thousands of years before that. But rather than one single culture, there were different cultures around the coast, the river valleys, and the highlands. Even today, around 30 percent of the Chinese population do not speak Putonghua, the national language. As well, citizens from Hong Kong and Inner Mongolia don’t appreciate Beijing’s attempts to “harmonise” their territories by imposing Putonghua in the place of local languages.

How and why was China invented? According to Hayton, as the Qing Dynasty was crumbling in 1912 and a new nationalist republic was being created, exiles like Liang Qichao and Sun Yat-sen, who had been living and writing overseas, developed new ways of thinking about nation, race, history, state, and territory. These ideas were inspired by modernising Western ideas and were transplanted into the minds of their compatriots through journalism and activism, which were picked up by the Chinese nationalist, revolutionary movement.

Since the Tiananmen Square incident, the Communist Party has embraced nationalism and is now trying to own Chinese nationalism. In recent decades, the Chinese Communist Party has further elaborated the nation’s constructed history through emphasising the idea of a nation humiliated by foreigners. This motivates many of its actions, notably in the South China Sea.

Hayton’s book surveys eight inventions — the invention of China, sovereignty, the Han Race, Chinese history, the Chinese nation, the Chinese language, a national territory, and a maritime claim. He highlights the effort to backdate the origin of Chinese culture to the “yellow emperor,” a mythical figure, with a mythical birthday 5,000 years ago, who is the ancestor of the Han race. He argues that Chinese nationalists in the late 19th and early 20th century turned the Manchu empire inside out, when they claimed Manchuria, Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Tibet as part of a Chinese empire. In short, nationalism, sovereignty, and the modern nation state do not have the historical depth in China as is officially presented. Yet today, the Chinese government is using ideas of race, common heritage, and the Yellow Emperor to court the loyalty of overseas Chinese communities.

In contrast to official histories, Hayton emphasises the Manchu (rather than Chinese) character of the Qing state. It practised different rules for different regions such that the emperor presented himself as a Manchu leader, Mongol leader, Tibetan leader, Muslim leader, or a Sinitic leader, according to the audience. The imperial court strived to maintain a Manchu identity, by maintaining Manchu customs. Manchu remained the official language of the Qing state right up until its collapse in 1912. Manchus lived in separate, usually walled, districts of cities, and intermarriage with a Chinese-identifying citizen was prohibited. At the time of the 1911/12 revolution, there were considerable acts of genocide against Manchu people.

The book is mainly a synthesis of academic studies from the new Qing history and the critical Han studies schools. Hayton’s main contribution is drawing on this research to help us better understand China’s challenges today, as the government seeks to impose a Chinese culture on areas like Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Tibet, which were not originally Chinese, and to unify Hong Kong and Taiwan with the mainland. His book takes inspiration from his previous book on the South China Sea where he argues that China’s claims are mainly based on “made-up history.”

Hayton does not seek to single out China with his thesis of the invention of China. No nation is a natural formation, they are all created, they are political constructs. The point is that China is no different from other countries in this respect – it is not more ancient, special, or authentic.

Hayton’s iconoclastic analysis has predictably provoked lively discussions in book presentations and social media. But it has also highlighted the fact that such open debates about China’s history are not possible inside China where history, notably “the century of humiliation,” is a key element of the Chinese Communist Party propaganda. This highlights the dark shadow over China’s education system which is tainted with official propaganda and is not open to critical thinking. It highlights the detriment of these truths on China’s challenges with nurturing the necessary human capital to foster innovation and continued economic success. Further, it reveals the fragility of a political system which rests on an historical foundation which is written and approved by the Chinese Communist Party rather than independent, academic historians.

Hayton’s book is a bit heavy going in parts, with much historical detail to wade through. But it is very much worth the effort to gain a deep understanding of the nature of the Chinese state.

This is a review of Bill Hayton, The Invention of China (Yale University Press, 2020). ISBN: 9780300234824 (hardcover) & 9780300257816 (paperback).

John West is adjunct professor at Tokyo’s Sophia University and executive director of the Asian Century Institute. His book Asian Century … on a Knife-Edge was reviewed in Australian Outlook.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License and may be republished with attribution.

Hayton examines each of the fundamental claims ranging from the unity of the Chinese language to the claims in the South China Sea and outlines exactly how these ideas came to dominate Chinese discourse about the country and its place in the world. The great irony is that for the most part, these so-called Chinese ideas of sovereignty or maritime claims are imported from Western countries, translated and filtered through a unique Chinese experience at the end of the Qing Dynasty, dealing with the collapse of the Empire and the encroachments of Western countries and Japan.

When removed from its nationalistic cage, the history of China is one of successive empires rising and falling, for many centuries it was the eastern provinces of either the Mongols, the Jurchens, the Manchus, or another regional actor amidst many. When contorted to fit the hallucinogenic haze of state-sponsored nationalism, the objections of the Uyghurs, Tibetans, Taiwanese, Hong Kongers, and anyone who doesn’t fit the preconceived mould of a member of the Zhonghua minzu are instead spectres of disunity, of political reform that has haunted the party leadership since 1989.

Hayton is clear and persuasive, his research is solid. His writing provides ample evidence to push back against the increasingly laughable claims spouted by Beijing. It allows for a deeper and more nuanced understanding of modern Chinese political thought and how central these ideas of unity are to maintaining the leadership’s control in the retreat of orthodox Maoism.

(less)

The basic premise of the book seems to be that China’s claims to a 5,000-year-old civilisation are somehow false – propaganda put about by the Chinese Communist Party. Hayton attempts to prove this by a variety of arguments, starting with the undisputed, I assume, fact that the intellectual underpinning of the idea of a Chinese nation-state was absorbed from European ideas in the 19th century. He suggests that since, prior to this, the region had been ruled over for thousands of years by a series of dynasties not all ethnically Chinese in origin, then modern China can’t count these periods as part of a Chinese history. I am therefore deleting Roman Britain, Viking Britain and Norman Britain from our own history and from now on declaring that any attempt to claim Hadrian’s Wall as part of British heritage is propaganda put about by the British Communist Party.

Hayton goes on to look at various different facets of Chinese culture and history to bolster up his argument, but I gave up on the book halfway through, since I found the arguments tenuous, shallow and not particularly well laid-out. And, to be honest, I’m not sure if the point is one that it was worth the effort of making. China is a fascinating nation with many facets, good and bad. It does many things I find objectionable, especially in terms of its human rights abuses. But this effort to deny it its claim to its history seems odd.

NB I received a free copy of the book without obligation to review from the publisher, Yale University Press via Amazon Vine UK.

www.fictionfanblog.wordpress.com (less)

The author has clearly conducted very detailed research in support of these arguments to produce a conclusion that it was Chinese students, sent abroad to study, who became radicalised to establish an agenda for a new Nation that could sustain the full territorial claims of 'The Great Manchu State' as its inhabitants referred to it, but more, leverage the then fashionable ideas of Social Darwinism to ensure Han ethnic supremacy within that state, having evicted the current Manchu rulers. The issue of who indeed was Han and who not was never quite resolved. Everywhere these students went they were mystified to hear foreigners refer to their homeland as 'China', but in their plans for a new nation it became the right catch-all word for the dream they wanted to promote.

A little reflection will show the implications of all this for China's foreign policy today; its numerous seemingly absurd territorial claims, both land and maritime; the frightening treatment of its minorities; and the curious obligations it is attempting to assert on its diaspora. From this perspective the logic of these policies starts to make a queer sort of sense.

This is not a book with which to start one's investigations into the history of the vast land we call China, (for that i would reccomend John Keay's, concise as possible but no more, opus) but it is a book that anyone seriously interested in China needs to read and consider before they conclude they have a comprehensive idea of what a 'true' history of 'China' might be. (less)

At heart, Hayton seeks to challenge the notion that China after a blip in the 19th & early 20th century, is merely returning to its 5000 years of historical pre-eminence and significance. Rather, he shows that much about what China is - where it is, who is in it, how it thinks of itself, even its very name 'China' - are products of the last 150 years, if not even younger.

This is not so much an intellectual history as a history of intellectuals. Hayton shows how many european ideas, such as Social Darwininsm, sovereignty and nationalism were adapted and introduced by Chinese thinkers into their society, with profound effects. He charts how the role of chance and circumstance - such as how otherwise obscure non-official map makers translated british texts or drew their lines a century ago - now leads to the threat of war in the South China Sea.

Hayton's skill is as a translator of academic work, synthesizing and bringing together important strands to tell a larger story. While I'm not a China specialist, I know of some of this work, and indeed there is a strong academic foundation the20.re (such as work showing the influence of Japan on Chinese economic thinking post WW2). Hayton has a clear personal position - one that seems to harden significantly as the book goes on - but has provided a credible and engaging account of the flow of ideas into China and its changes.

On one hand, this is an important book because the narratives we tell are crucial to how we see the world. We err in seeing China as somehow impervious to change, always its own unique stream, rather than part of the global exchange of ideas. Indeed, Hayton ends by arguing China today is less Chinese (in the sense of reflecting the 5000 years before) and more a by-product of the 1930s, nationalist and socialist, ready to fight wars over territory (Taiwan, James Shoal) which as a nation it had ignored or only came to claim by happenstance along the way.

On the other hand, the size of China's material forces are so large that even if 'happenstance' is how they got here, poking a hole in the CCP's narrative doesn't really do much to change. They won't abandon the demand to control Taiwan once they learn that the Ching empire and early Republican government had almost no historic claim to the island (and indeed legally abandoned it to Japan just before the 20th century). Change is possible, these ideas matter, but it also feels slightly academic, even more so because Hayton clearly seems to wish the book would matter more for current politics.

If this is a story of ideas flowing into China, the reader is left to wonder whether future books will chart the flow of ideas out of China into other prominent countries around the world. Not in the crude 'Beijing consensus' model the odd authoritarian might try to emulate, but the way deep ideas about how society should be organised, the relationship between people and their government and the kinds of communities we build may change in the coming century.

The sad part is, the china of 5000 years is a much more viable regional and global power, one that may be better suited to a modern world, than the CCP led menace currently claiming its authority while thinking in terms of outdated European ideas of nationalism, race and intense sovereign authority. (less)

However, in seeking to dismantle the narrative that China is 5,000-year-old civilisation that has been throughout its history been, with a few exceptions, a unified country on a single piece of territory, with a majority people, culture and language, Hayton overstates his case. He seems to fail to grasp the force of his own argument: that the markers of nationhood and group identity he surveys—a state name; national sovereignty tied to a Chinese ethnicity; a single, majority Chinese language; and a territory with a defined border—are Modern, Western concepts of defines a state, and therefore the fact that the “great states” (it’s not clear why the term “empire” is rejected) that preceded the Republic of China lacked these is not evidence that a Chinese cultural identity and political entity did not exist prior to 1912.

The book’s main strength is in demonstrating how the current regime’s narrative of national history is anachronistic, and built upon fragile and dangerous conceptions of nationalism, race, and progress that have largely been abandoned by the Western powers that invented them.

3.5 stars. (less)

On one level it accommodates those without a deep knowledge of Chinese (or even so-called modern) history but on another it delves deeper into specific themes than initially expected.

All larger countries, and many smaller ones, have travelled a crooked path across many centuries in a way that continues to inform their early 21st C narrative. The leadership of China is not alone in massaging and manipulating this. Brazil, India, Russia, Turkey, the USA all leap immediately to mind.

That said, bringing these reference points out into the open has power. As Mark Twain observed, "History doesn't repeat itself, but it often rhymes”. Some might say Hayton's book promotes anti-Chinese sentiment but I think its greatest value is in raising awareness of how certain decisions made at critical junctures in history echo long afterward ... within what we currently understand to be China, and elsewhere. (less)

No comments:

Post a Comment