Australia’s South Korea problem

Associate Professor Jeffrey Robertson and Addie Gerszberg

Despite its increasing international reputation as a global middle power, the tremendous success of its culture exports, and recognition of its effective governance, South Korea faces an image problem in Australia. The Australian community, particularly the foreign policy community, continue to narrowly view the Korean Peninsula in the context of North Korea.

South Korea is an important political partner for Australia, its fourth largest trading partner, and a rapidly growing cultural influence. There are over 123,000 Australians who claim Korean ancestry, and nearly 100,000 of these were born in South Korea. With the highest proportion in the world of students undertaking tertiary education, and the rapid adaptation to online education as a result of the coronavirus, South Korea holds enormous potential as future source of students in the now struggling tertiary education sector. Studies estimate that a unified Korean peninsula would potentially have a GDP surpassing that of Germany or Japan. Australia’s attention should be squarely aimed at South Korea.

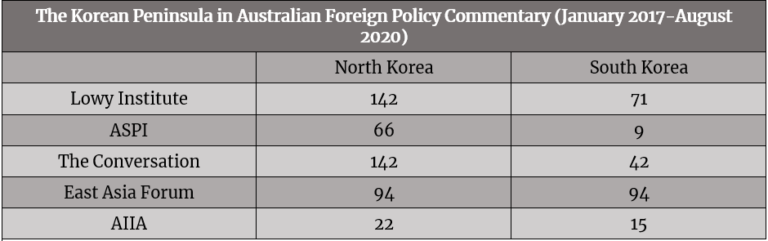

Yet, our research shows that in Australia’s foreign policy commentary, there are actually more pieces on the Australia – North Korea relationship than there are on the Australia – South Korea relationship. This is despite the fact that Australia’s political, economic, and cultural relations with North Korea are virtually non-existent. A review of the Korean peninsula in Australia’s five major foreign policy commentary venues: Interpreter; Strategist; East Asia Forum; Conversation; and Australian Outlook; provides some insight and brings out the key challenges of Australia’s South Korea problem.

Our research shows that Australians overwhelmingly see the Korean peninsula through a security lens. The vast majority of Australian foreign policy commentary about the Korean Peninsula focuses on North Korea’s authoritarian leadership and/or its nuclear weapons and ballistic missile programs. The obsession with all things North Korea means those normally focused on human rights, negotiation, Japan, international law, global health, and security, will sooner or later, write something on North Korea.

Of course, this is not wholly unexpected, and is not limited to Australia. Over last 20 years, the Institute of International Strategic Studies refereed journal Survival, had 17 articles with ‘North Korea’ in the title and only one article with “South Korea” in the title. The journal had 393 articles with the term ‘North Korea’ and 292 articles with the term ‘South Korea’. Most leading refereed journals reflect this imbalance. In the most esteemed levels of academia, let alone short-piece media commentary, hype and North Korea clickbait rules.

Any conflict on the Korean peninsula would involve decisions made in Seoul as well as decisions made in Pyongyang. The widespread fear is that North Korea could make a unilateral decision to launch a nuclear weapon, but such as decision would effectively end the North Korean state, because of the retaliatory nature of South Korea’s allies. The reality is that tension on the Korean Peninsula occurs in the context of provocation and escalatory paths, where both the initiator and the responder have the same options to escalate or manage, so in strategic terms, the trajectory of any crisis on the Korean peninsula is affected as much by the responder’s move as the initiator’s move. How Seoul responds to provocations is just as significant as the provocation itself.

If Seoul had responded differently in previous provocations, such as the March 2010 sinking of the Pohang-class naval corvette, Cheonan, or the November 2010 Yeonpyeong Island bombardment, the crises would have followed an entirely different path. Yet, commentators prefer to speculate on events in Pyongyang to determine whether they will provoke, rather than assess events in Seoul to determine how they would respond.

This imbalance is also reflected in the mainstream media. Nearly every political visit to South Korea covered by the Australian media includes ubiquitous variations of images of the ‘DMZ’. There are alternatives. The vast mounds Pilbara red dust in Ulsan from the unloading of Australian iron ore (a little bit of Australia in South Korea), the lines of cars waiting to be driven onto container ships, as the transformed iron ore returns to Australia, or the megapolis of Gangnam and the colorful cultural exports of K-culture – all beg for a more balanced visual portrayal of the Australia-Korea relationship.

Influencing the Australian strategic studies community to not see South Korea’s fate determined by the structure of geopolitics in the region, but rather see South Korea as having agency to influence and transform the region, is the first challenge to be overcome.

There’s a relatively small number of commentators who focus on the Korean peninsula. While discussion of North Korea brings in a range of commentators from other fields, the number of commentators who regularly write on South Korea is very small. This has both negative and positive implications.

On the negative side, with the small number of regular commentators, it’s more difficult to get wide coverage on topics South Korea deems significant: think the Korea-Japan Dokdo/Takeshima territorial dispute or South Korea’s North Korea policy aims. While rarely openly discussed, South Korea’s vision for North Korea is distinct from the US and Australia. Put crudely, North Korea’s possession of nuclear and ballistic weapons programs do not make a difference to a state with its capital within range of massed artillery. More important is de-escalation, confidence building, stability, and ultimately predictability. Reducing the propensity for provocation, even if it means allowing denuclearisation to take second place, is more important to Seoul.

On the positive side, with a relatively small number of commentators, it’s conceivably easier to cultivate and potentially influence a fuller and more nuanced discussion of the Korean pensinsula and Australia’s relationship with South Korea. Greater and more consistent interaction between the Australian and South Korean strategic communities could lead to greater consensus or at least understanding on the different approaches to address Korean Peninsula security issues.

Finally, there is only a very small number of articles that focus on Australia’s foreign policy on South Korea. It is as important to increase the relevance of Australia to South Korea, as it is to correct our own tendency to view the Korean Peninsula in the context of North Korea.

Australia does not attract as much interest in South Korea as most Australians would presume. Australia very rarely makes an appearance in South Korean language foreign policy commentary; it is covered in the foreign ministry by a junior officer (also covering Afghanistan and New Zealand); and is often perceived by South Korean government officials as maintaining a foreign policy that’s merely a reflection of US policy.

Just under ten years ago, the South Korean embassy in Canberra battled relentlessly

(and ultimately successfully) to have Korean included as a Priority Asian Language in the Australia in Asia White Paper. More recently, Australia demonstrated only limited interest in the current South Korean government’s key foreign policy initiative, the New Southern Policy, in which Australia could have pushed for inclusion.

Australia could do more to increase its relevance in South Korea and raise awareness of the bilateral relationship through various channels of soft power. These should include increasing support for academic and media exchanges and strengthening Australian studies in Korea. Building more effective (localised) digital diplomacy could also be effective. Social media, including platforms, usage, content, and penetration, is distinct in South Korea. For example, public expectations regarding embassy content on webpages and social media accounts in South Korea do not fit the standard mold. Listing high-level meetings with colorful images and smiling politicians may fit in other countries, but with a high degree of unpopularity (and in some cases illegality) associated with previous administrations, special attention needs to be paid to content depicting relationships between leaders in the recent past. More localised content is the answer. One way to achieve this is to encourage influence multipliers, such as expatriate, sports, student, and cultural associations, chambers of commerce and industry, or academic associations.

Australian studies centres can act as powerful multipliers, with local academics engaged in social media able to better promote locally relevant content and information. Australia attracts more attention in China and Japan, where the Australian Government and Australian industry support multiple centers for Australian studies. Unfortunately, there is only one Australian studies centre in South Korea, which consists of a single dedicated academic who maintains a Facebook page, routinely struggles for funding, and attracts scant media interest. In contrast, there are now a number of Korean studies institutes spread across Australia with well-educated, highly-skilled and internationally-respected researchers. The majority of these institutes, with a focus on humanities and language, act as a solid base from which stronger interest, and ultimately policy relevance, grows. There are currently no courses on Australian history, literature, or even foreign policy, taught in South Korea. Supporting Australian studies in Korea, and in turn promoting Australia as relevant to South Korea’s foreign policy interests is a major challenge to overcome.

Reviewing Australia’s five major foreign policy commentary publications highlights one point above all – with so few challenges, and each one able to be put off to a later date, the Australia – South Korea bilateral relationship may ultimately be a victim of its own success.

Jeffrey Robertson is an Associate Professor of Diplomatic Studies at Yonsei University in South Korea. Addie Gerszberg is a Yonsei University student, currently focusing US foreign policy and East Asia.

Image: South Korean-made cars on a dock in Sydney, Australia. Credit: James Porteous, CSIRO/WikimediaCommons

Date: November 22, 2020

Australia’s South Korea problem

Associate Professor Jeffrey Robertson and Addie Gerszberg

Despite its increasing international reputation as a global middle power, the tremendous success of its culture exports, and recognition of its effective governance, South Korea faces an image problem in Australia. The Australian community, particularly the foreign policy community, continue to narrowly view the Korean Peninsula in the context of North Korea.

South Korea is an important political partner for Australia, its fourth largest trading partner, and a rapidly growing cultural influence. There are over 123,000 Australians who claim Korean ancestry, and nearly 100,000 of these were born in South Korea. With the highest proportion in the world of students undertaking tertiary education, and the rapid adaptation to online education as a result of the coronavirus, South Korea holds enormous potential as future source of students in the now struggling tertiary education sector. Studies estimate that a unified Korean peninsula would potentially have a GDP surpassing that of Germany or Japan. Australia’s attention should be squarely aimed at South Korea.

Yet, our research shows that in Australia’s foreign policy commentary, there are actually more pieces on the Australia – North Korea relationship than there are on the Australia – South Korea relationship. This is despite the fact that Australia’s political, economic, and cultural relations with North Korea are virtually non-existent. A review of the Korean peninsula in Australia’s five major foreign policy commentary venues: Interpreter; Strategist; East Asia Forum; Conversation; and Australian Outlook; provides some insight and brings out the key challenges of Australia’s South Korea problem.

Our research shows that Australians overwhelmingly see the Korean peninsula through a security lens. The vast majority of Australian foreign policy commentary about the Korean Peninsula focuses on North Korea’s authoritarian leadership and/or its nuclear weapons and ballistic missile programs. The obsession with all things North Korea means those normally focused on human rights, negotiation, Japan, international law, global health, and security, will sooner or later, write something on North Korea.

Of course, this is not wholly unexpected, and is not limited to Australia. Over last 20 years, the Institute of International Strategic Studies refereed journal Survival, had 17 articles with ‘North Korea’ in the title and only one article with “South Korea” in the title. The journal had 393 articles with the term ‘North Korea’ and 292 articles with the term ‘South Korea’. Most leading refereed journals reflect this imbalance. In the most esteemed levels of academia, let alone short-piece media commentary, hype and North Korea clickbait rules.

Any conflict on the Korean peninsula would involve decisions made in Seoul as well as decisions made in Pyongyang. The widespread fear is that North Korea could make a unilateral decision to launch a nuclear weapon, but such as decision would effectively end the North Korean state, because of the retaliatory nature of South Korea’s allies. The reality is that tension on the Korean Peninsula occurs in the context of provocation and escalatory paths, where both the initiator and the responder have the same options to escalate or manage, so in strategic terms, the trajectory of any crisis on the Korean peninsula is affected as much by the responder’s move as the initiator’s move. How Seoul responds to provocations is just as significant as the provocation itself.

If Seoul had responded differently in previous provocations, such as the March 2010 sinking of the Pohang-class naval corvette, Cheonan, or the November 2010 Yeonpyeong Island bombardment, the crises would have followed an entirely different path. Yet, commentators prefer to speculate on events in Pyongyang to determine whether they will provoke, rather than assess events in Seoul to determine how they would respond.

This imbalance is also reflected in the mainstream media. Nearly every political visit to South Korea covered by the Australian media includes ubiquitous variations of images of the ‘DMZ’. There are alternatives. The vast mounds Pilbara red dust in Ulsan from the unloading of Australian iron ore (a little bit of Australia in South Korea), the lines of cars waiting to be driven onto container ships, as the transformed iron ore returns to Australia, or the megapolis of Gangnam and the colorful cultural exports of K-culture – all beg for a more balanced visual portrayal of the Australia-Korea relationship.

Influencing the Australian strategic studies community to not see South Korea’s fate determined by the structure of geopolitics in the region, but rather see South Korea as having agency to influence and transform the region, is the first challenge to be overcome.

There’s a relatively small number of commentators who focus on the Korean peninsula. While discussion of North Korea brings in a range of commentators from other fields, the number of commentators who regularly write on South Korea is very small. This has both negative and positive implications.

On the negative side, with the small number of regular commentators, it’s more difficult to get wide coverage on topics South Korea deems significant: think the Korea-Japan Dokdo/Takeshima territorial dispute or South Korea’s North Korea policy aims. While rarely openly discussed, South Korea’s vision for North Korea is distinct from the US and Australia. Put crudely, North Korea’s possession of nuclear and ballistic weapons programs do not make a difference to a state with its capital within range of massed artillery. More important is de-escalation, confidence building, stability, and ultimately predictability. Reducing the propensity for provocation, even if it means allowing denuclearisation to take second place, is more important to Seoul.

On the positive side, with a relatively small number of commentators, it’s conceivably easier to cultivate and potentially influence a fuller and more nuanced discussion of the Korean pensinsula and Australia’s relationship with South Korea. Greater and more consistent interaction between the Australian and South Korean strategic communities could lead to greater consensus or at least understanding on the different approaches to address Korean Peninsula security issues.

Finally, there is only a very small number of articles that focus on Australia’s foreign policy on South Korea. It is as important to increase the relevance of Australia to South Korea, as it is to correct our own tendency to view the Korean Peninsula in the context of North Korea.

Australia does not attract as much interest in South Korea as most Australians would presume. Australia very rarely makes an appearance in South Korean language foreign policy commentary; it is covered in the foreign ministry by a junior officer (also covering Afghanistan and New Zealand); and is often perceived by South Korean government officials as maintaining a foreign policy that’s merely a reflection of US policy.

Just under ten years ago, the South Korean embassy in Canberra battled relentlessly

(and ultimately successfully) to have Korean included as a Priority Asian Language in the Australia in Asia White Paper. More recently, Australia demonstrated only limited interest in the current South Korean government’s key foreign policy initiative, the New Southern Policy, in which Australia could have pushed for inclusion.

Australia could do more to increase its relevance in South Korea and raise awareness of the bilateral relationship through various channels of soft power. These should include increasing support for academic and media exchanges and strengthening Australian studies in Korea. Building more effective (localised) digital diplomacy could also be effective. Social media, including platforms, usage, content, and penetration, is distinct in South Korea. For example, public expectations regarding embassy content on webpages and social media accounts in South Korea do not fit the standard mold. Listing high-level meetings with colorful images and smiling politicians may fit in other countries, but with a high degree of unpopularity (and in some cases illegality) associated with previous administrations, special attention needs to be paid to content depicting relationships between leaders in the recent past. More localised content is the answer. One way to achieve this is to encourage influence multipliers, such as expatriate, sports, student, and cultural associations, chambers of commerce and industry, or academic associations.

Australian studies centres can act as powerful multipliers, with local academics engaged in social media able to better promote locally relevant content and information. Australia attracts more attention in China and Japan, where the Australian Government and Australian industry support multiple centers for Australian studies. Unfortunately, there is only one Australian studies centre in South Korea, which consists of a single dedicated academic who maintains a Facebook page, routinely struggles for funding, and attracts scant media interest. In contrast, there are now a number of Korean studies institutes spread across Australia with well-educated, highly-skilled and internationally-respected researchers. The majority of these institutes, with a focus on humanities and language, act as a solid base from which stronger interest, and ultimately policy relevance, grows. There are currently no courses on Australian history, literature, or even foreign policy, taught in South Korea. Supporting Australian studies in Korea, and in turn promoting Australia as relevant to South Korea’s foreign policy interests is a major challenge to overcome.

Reviewing Australia’s five major foreign policy commentary publications highlights one point above all – with so few challenges, and each one able to be put off to a later date, the Australia – South Korea bilateral relationship may ultimately be a victim of its own success.

Jeffrey Robertson is an Associate Professor of Diplomatic Studies at Yonsei University in South Korea. Addie Gerszberg is a Yonsei University student, currently focusing US foreign policy and East Asia.

Image: South Korean-made cars on a dock in Sydney, Australia. Credit: James Porteous, CSIRO/WikimediaCommons

Date: November 22, 2020 |

No comments:

Post a Comment