소련-일본 전쟁

| 소련-일본 전쟁 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 제2차 세계 대전, 태평양 전쟁, 중일 전쟁의 일부 | |||||||

대일전승일을 위해 축배를 드는 미국-소련 수병들 | |||||||

| |||||||

| 교전국 | |||||||

| 지휘관 | |||||||

소련-일본 전쟁(Советско-японская война) 또는 소련 대일 참전이란 소련이 제2차 세계 대전 말기에 영토 확장을 위해 일본 제국과의 소련-일본 중립 조약을 파기하고 8월 9일 일본 제국을 침공하여 발발한 전쟁을 말한다. 한반도 분단의 결정적 원인이 되었다.

전개[편집]

소련은 얄타 회담을 통해 1945년 8월 초 일본 제국과 맺은 소비에트 연방-일본 중립 조약을 파기하고 일본 제국에게 선전 포고를 하여 일본 제국과 소련의 전쟁이 만주국에서 펼쳐졌다[1] . 그리고 이 전쟁을 통해서 사할린 섬 남쪽도 탈환하였다.[2]

히로시마에 원자 폭탄이 투하되기 전까지만 해도 소련은 대일 참전에 소극적인 입장을 견지하고 있었다. 일본의 항복을 앞당기기 위한 연합국들의 채근에도 묵묵부답이었다. 일본의 무조건 항복을 권고하는 것을 주요 내용으로 하는 2주 전의 포츠담 선언에서도 빠졌다. 1941년 일본과 체결한 불가침 조약이 여전히 유효한 상태라는 게 표면상의 이유였다.

그러나 수면 아래서는 계속해서 대일 참전의 실리를 저울질하고 있었다. 홋카이도 분할 통치를 대일 참전의 요구 조건으로 내세우는 등 전후 동북아시아에서의 영향력 확보를 위해 최대한 몸값을 높이는 전술을 구사한 것이다.

이런 와중에 미국이 원자 폭탄을 히로시마에 투하, 결정적으로 일본의 패망을 앞당기자 허겁지겁 일본에 선전 포고한 것이다. 결국 소련은 히로시마에 원자 폭탄이 투하된 지 이틀 뒤인 1945년 8월 8일 부랴부랴 대일 선전 포고를 하고 포츠담 선언에 합류했다. 일주일 뒤 히로히토(裕仁) 일본 천황의 무조건 항복 선언이 나왔다.

중국령 만주에서 승리한 소련은 만주국을 멸망시켰고 8월 9일에는 한반도의 웅기, 나진으로 진출하여 마침내 11일에 점령하였다[3]. 이후 남진을 계속하면서 8월 13일에 청진으로 진출하였다.[4] 그리고 일본 제국이 8월 15일에 정식으로 항복함으로써 한반도는 소련, 미국 군정으로 분단되었다.[5][6]

이후[편집]

각주[편집]

- ↑ Battlefield II The Battle of Manchuria World War II

- ↑ 대한민국 6년역사가 움직인 순가늘 1부

- ↑ “유지시거”. 2016년 3월 4일에 원본 문서에서 보존된 문서. 2019년 8월 31일에 확인함.

- ↑ 러시아 소장 북한 영상기록물 최초 공개 Archived 2014년 1월 11일 - 웨이백 머신 2006-05-18 16:35

- ↑ 이제는 말할 수 있다 분단의 기원

- ↑ Battlefield II The Battle of Manchuria World War II

ソ連対日参戦

この記事の内容の信頼性について検証が求められています。 確認のための文献や情報源をご存じの方はご提示ください。出典を明記し、記事の信頼性を高めるためにご協力をお願いします。議論はノートを参照してください。(2017年2月) |

| 対ソ防衛戦 | |

|---|---|

| 戦争:太平洋戦争 | |

| 年月日:1945年(昭和20年)8月9日 - 1945年(昭和20年)9月5日[1][2] | |

| 場所:満州国 樺太 千島列島 内蒙古 朝鮮北部 北支 | |

| 結果: | |

| 交戦勢力 | |

| 指導者・指揮官 | |

| 戦力 | |

| 1,217,000[3] | ソ連 1,577,225 モンゴル 16,000 |

| 損害 | |

| 戦死 21,389〜84,000 戦傷 20,000[4] 捕虜 594,000 | 戦死 9,726〜20,000 戦傷 24,425 |

ソ連対日参戦(ソれんたいにちさんせん)とは、満州国において1945年(昭和20年)8月9日未明に開始された日本の関東軍、支那派遣軍と極東ソ連軍との間で行われた満州・北朝鮮・北支における一連の作戦・戦闘と、日本の第五方面軍とソ連の極東ソ連軍との間で行われた南樺太・千島列島における一連の作戦・戦闘である。ソ連は満洲・樺太・千島侵攻のため、総兵力147万人、戦車・自走砲5250輌、航空機5170機を準備し、9日未明、満洲への侵攻作戦を、11日に樺太への侵攻作戦を開始し、千島では18日に占守島への上陸を開始した[5]。

日ソ中立条約を破棄したソ連軍による侵攻・領土略奪であるが、ソ連側はこれに先立つ関東軍特種演習の段階で、同条約が事実上破棄されたものとしている[要出典]。日本の防衛省防衛研究所戦史部では、この一連の戦闘を「対ソ防衛戦」と呼んでいるが、ここでは日本の検定済歴史教科書でも一般的に用いられている「ソ連対日参戦」[要出典]を使用する。

背景[編集]

19世紀の帝政ロシアの時代から日本は対露(対ソ)の軍事的な衝突を予想し、その準備を進めていた。ロシア革命後、ソ連は世界を共産主義化することを至上目標に掲げ、ヨーロッパ並びに東アジアへ勢力圏を拡大しようと積極的であった。極東での日ソの軍拡競争は1933年(昭和8年)からすでに始まっており、当時の日本軍は対ソ戦備の拡充のために、本国と現地が連携し、関東軍がその中核となって軍事力の育成を推進したが、1936年(昭和11年)ごろには戦備に決定的な開きが現れており、師団数、装備の性能、陣地・飛行場・掩蔽施設の規模内容、兵站にわたって極東ソ連軍の戦力は関東軍のそれを大きく凌いでいたと言われる。

張鼓峰事件やノモンハン事件において日ソ両軍は戦闘を行い、関東軍はその戦力差を認識したが、陸軍省では南進論が力を得て、関心は東南アジアへと移っており、軍備の重点も太平洋戦争勃発で南方へと移行する。1943年(昭和18年)以降は南方における戦局の悪化によって、関東軍の戦力を南方戦線へ振り分けざるを得なくなった。

満洲国における日本軍の軍事力が低下する一方で、ドイツ軍は敗退を続け、ついに1945年(昭和20年)5月8日にナチス・ドイツが降伏した(ヨーロッパ戦勝記念日)ことにより、ソ連軍にヨーロッパ戦線から撤収する余力が生じ、ソ連の対日参戦が現実味を帯び始める。

情勢認識[編集]

クルスクの戦いで対ドイツ戦で優勢に転じたソ連に対し、同じころ対日戦で南洋諸島を中心に攻勢を強めていたアメリカでは、太平洋戦争での日本の降伏のため、ルーズベルトはソ連への対日参戦が必須条件としていた。1943年(昭和18年)10月、連合国のソ連、イギリス、アメリカはモスクワで外相会談を持ち、コーデル・ハル国務長官からモロトフ外相にルーズベルトの意向として、千島列島と樺太をソ連領として容認することを条件に参戦を要請した。このときソ連はナチス・ドイツを敗戦させた後に参戦する方針と回答した。

1945年(昭和20年)2月のヤルタ会談ではこれを具体化し、ドイツ降伏後3ヵ月での対日参戦を約束。ソ連は1945年(昭和20年)4月には、1941年(昭和16年)に締結され、5年間の有効期間を持つ「日ソ中立条約の延長を求めない」ことを、日本政府に通告した。ヨーロッパ戦勝記念日後は、シベリア鉄道をフル稼働させて、ソビエト社会主義共和国連邦と満州国との国境に、巨大な陸軍による軍事力の集積を行った。

日本政府は、ソ連との日ソ中立条約を頼みに、ソ連を仲介した連合国との外交交渉に働きかけを強めて、絶対無条件降伏ではなく国体保護や国土保衛を条件とした有条件降伏に何とか持ち込もうとした。しかしソ連が中立条約の不延長を宣言したことや、ソ連軍の動向などから、ドイツの降伏一ヵ月後に戦争指導会議において総合的な国際情勢について議論がなされ、ソ連の国家戦略、極東ソ連軍の状況、ソ連の輸送能力などから「ソ連軍の攻勢は時間の問題であり、今年(1945年(昭和20年))の8月か遅くても9月上旬あたりが危険」「8月以降は厳戒を要する」と結論付けている。

関東軍首脳部は、日本政府に比べて事態を重く見ていなかった。総司令官は1945年(昭和20年)8月8日には新京を発ち、関東局総長に要請されて結成した国防団体の結成式に参列していたことに、それは表れている。時の山田総司令官は戦後に「ソ軍の侵攻はまだ先のことであろうとの気持ちであった」と語っている。ただし、山田総司令官は事態急変においては直ちに新京に帰還できる準備を整えており、事実ソ連軍の攻勢作戦が発動して、すぐに司令部に復帰している。

なお、6月に大本営の第五課課長白木末政大佐は新京において、状況の切迫性を当時の関東軍総参謀長に説得したところ、「東京では初秋の候はほとんど絶対的に危機だとし、今にもソ軍が出てくるようにみているようだが、そのように決め付けるものでもあるまい」と反論したと言われており、ソ連軍の攻勢をある程度予期していながらも、重大な警戒感は持っていなかった[要出典]。

関東軍第一課(作戦課)においては、参謀本部の情勢認識よりも遥かに楽観視していた。この原因は作戦準備が全く整っておらず、戦時においては任務の達成がほぼ不可能であるという状況がもたらした「希望的観測」が大きく影響した。当時の関東軍は少しでも戦力の差を埋めるために、陣地の増設と武器資材の蓄積を急ぎ、基礎訓練を続けていたが、ソ連軍の侵攻が冬まで持ち越してもらいたいという願望が、「極東ソ連軍の後方補給の準備は10月に及ぶ」との推測になっていた。

つまり、関東軍作戦課においては、1945年(昭和20年)の夏に厳戒態勢で望むものの、ドイツとの戦いで受けた損害の補填を行うソ連軍は、早くとも9月以降、さらには翌年に持ち越すこともありうると判断していたのだった。この作戦課の判断に基づいて作戦命令は下され、指揮下全部隊はこれを徹底されるものであった。

関東軍の前線部隊においては、ソ連軍の動きについて情報を得ており、第三方面軍作戦参謀の回想によれば、ソ連軍が満ソ国境三方面において兵力が拡充され、作戦準備が活発に行われていることを察知、特に東方面においては火砲少なくとも200門以上が配備されており、ソ連軍の侵攻は必至であると考えられていた。そのため8月3日、直通電話によって関東軍作戦課の作戦班長草地貞吾参謀に情勢判断を求めたところ、「関東軍においてソ連が今直ちに攻勢を取り得ない体勢にあり、参戦は9月以降になるであろうとの見解である」と回答があった。その旨は関東軍全体に明示されたが、8月9日早朝、草地参謀から「みごとに奇襲されたよ」との電話があった、と語られている。

さらに第四軍司令官上村幹男中将は、情勢分析に非常に熱心であり、7月ころから絶えず北および西方面における情報を収集し、独自に総合研究したところ、8月3日にソ連軍の対日作戦の準備は終了し、その数日中に侵攻する可能性が高いと判断したため、第四軍は直ちに対応戦備を整え始めた。また8月4日に関東軍総参謀長がハイラル方面に出張中と知り、帰還途上のチチハル飛行場に着陸を要請し、直接面談することを申し入れて見解を伝えたものの、総参謀長は第四軍としての独自の対応については賛同したが、関東軍全体としての対応は考えていないと伝えた。そこで上村軍司令官は部下の軍参謀長を西(ハイラル)方面、作戦主任参謀を北方面に急派してソ連軍の侵攻について警告し、侵攻が始まったら計画通りに敵を拒止するように伝えた。

他方、北海道・樺太・千島方面を管轄していた第五方面軍は、アッツ島玉砕やキスカ撤退により千島への圧力が増大したことから、同地域における対米戦備の充実を志向、樺太においても国境付近より南部の要地の防備を勧めていた。が、1945年(昭和20年)5月9日、大本営から「対米作戦中蘇国参戦セル場合ニ於ケル北東方面対蘇作戦計画要領」で対ソ作戦準備を指示され、再び対ソ作戦に転換する。このため、陸上国境を接する樺太の重要性が認識されるが、兵力が限られていたことから、北海道本島を優先、たとえソ連軍が侵攻してきたとしても兵力は増強しないこととした。

しかし、上記のような戦略転換にもかかわらず、国境方面へ充当する兵力量が定まらないなど、実際の施策は停滞していた。千島においては既に制海権が危機に瀕していることから、北千島では現状の兵力を維持、中千島兵力は南千島への抽出が図られた。

樺太において、陸軍の部隊の主力となっていたのは第88師団であった。同師団は偵察等での状況把握や、ソ連軍東送の情報から8月攻勢は必至と判断、方面軍に報告すると共に師団の対ソ転換を上申したが、現体勢に変化なしという方面軍の回答を得たのみだった。

対ソ作戦計画が整えられ、各連隊長以下島内の主要幹部に対ソ転換が告げられたのは、8月6・7日の豊原での会議においてのことであった。千島においては、前記の大本営からの要領でも、地理的な関係もあり対米戦が重視されていたが、島嶼戦を前提とした陣地構築がなされていたため、仮想敵の変更は、それほど大きな影響を与えなかった。

作戦の概要[編集]

ソ連軍[編集]

ソ連の有利を生み出したのは数ではなく、訓練と装備、そして戦術だった[6]。

ソ連戦史によれば、対ソ防衛戦におけるソ連軍の攻勢作戦の概要としては、第一にシベリア鉄道による鉄道輸送を用いて圧倒的な兵力を準備し、第二にその集中した膨大な戦力を秘匿しつつ、満州地方に対して東西北からの三方面軍に編成して分進合撃を行い、第三に作戦発動とともに急襲を加え、速戦即決の目的を達することがあげられる。微視的に看れば、ソ連軍は西方面においては左翼一部を除いて大部分は遭遇戦の方式でもって日本軍を撃滅しようとし、一方東方面においては徹底的な陣地攻撃の方式をとっている。北方面は東西の戦局を見極めながらの攻撃という支援的な作戦であった。北樺太及びカムチャツカ方面では、開戦の初期は防衛にあたり、満洲国における主作戦の進展次第で、南樺太および千島列島への進攻を行なうこととした。

当初ソ連軍の満州侵攻作戦計画は同方向の攻勢軸に大兵力を集中投入する伝統的な突破戦略であり、攻撃方向は北満の牡丹江・チチハル方面へと向けられていた。しかし満州北東部に配置された関東軍の強固な要塞地帯の妨害が予想され、突破後の関東軍主力の殲滅を考慮した場合、北満からの単調な攻勢は日本軍主力を取り逃がす危険性があった。そこで極東ソ連軍総司令官ワシレフスキー元帥のもとで、3個の正面軍(ザバイカル・第1極東・第2極東)が編成され、新たな対日作戦計画が立案された。ソ連軍首脳部は、独ソ戦の経験に基づいた迂回機動による包囲と縦深侵攻を組み合わせた戦略を新たに採用し、3方向からの新たな攻勢戦略を立案。3方面から満州内部に向けて進撃し、第1極東正面軍とザバイカル正面軍が東西両端から新京・吉林付近で合流し、関東軍を南北に分断、第2極東正面軍と共に北に残された関東軍部隊を巨大な包囲網の中で殲滅する。ソ連極東軍が擁する唯一の機械化軍である第6親衛戦車軍は大興安嶺と砂漠地帯が立ちはだかる北西・西部正面のザバイカル正面軍に配置された。北東・東部正面は関東軍主力と要塞群が密集しており、関東軍の意表をついた縦深侵攻を実現させるためにも、あえて戦車・機械化部隊の進撃が困難と予測される西正面に投入されることとなった。最高総司令部の構想では、これらの機械化兵力は日本軍の孤立した抵抗拠点の全てを迂回し、迅速に砂漠地帯を横断して、日本側が脅威を認識する前に大興安嶺の峠道を制圧することになっていた[7]。満州での作戦に備え赤軍の軍事機構は極端に特殊化されていた[7]。どの狙撃師団(歩兵師団)も独立戦車旅団一個、自走砲連隊一個、砲兵連隊2個を持ち、縦深の突破と追撃用の先遣隊を編成することが可能となっていた[7]。西部からの戦略的突破を担当する第6親衛戦車軍も再編され、2個戦車軍団のうち1個が機械化軍団に置き換えられ、2個自走砲旅団、2個軽野砲旅団に支援部隊が加わり、戦車・自走砲1019両を擁した[7]。この編成は独ソ戦時の戦車軍よりも、1946年に編成された機械化軍や1941年の機械化軍団に近かった[7]。最高総司令部は戦後の理想的な軍隊を編成する場として満州を選び、のちの標準となる様々な新しい組織と概念を試験しようとしていた[7]。満州での作戦は、その後何十年にもわたってソ連陸軍で研究されるほどの機動戦の傑作となった[7]。

南樺太および千島列島への進攻に関してはソ連海軍、特に太平洋艦隊は艦艇不足であった。このため事前にレンドリースの一環としてアラスカにおいてアメリカとソ連の合同で艦艇の貸与と乗組員の訓練を行うフラ計画が実行された[8]。

戦闘序列[編集]

極東ソビエト軍総司令官アレクサンドル・ヴァシレフスキーソ連邦元帥

モンゴル人民革命軍総司令官ホルローギーン・チョイバルサン元帥

- 第1極東戦線:司令官キリル・メレツコフソ連邦元帥

- 第1赤旗軍:司令官アファナシー・ベロボロドフ大将

- 第5軍:司令官ニコライ・クルイロフ大将

- 第25軍:司令官イワン・チスチャコフ大将

- 第35軍

- 第10機械化軍団

- 第9航空軍

- 第2極東戦線:司令官マクシム・プルカエフ上級大将

- 第2赤旗軍

- 第15軍

- 第16軍:司令官レオンチー・チェレミソフ少将

- 第10航空軍

- 第5独立狙撃軍団

- カムチャッカ防衛地区:司令官アレクセイ・グネチコ少将

- ザバイカル戦線:司令官ロディオン・マリノフスキーソ連邦元帥

- 第17軍

- 第36軍:司令官アレクサンドル・ルチンスキー

- 第39軍

- 第53軍

- 第6親衛戦車軍:司令官アンドレイ・クラフチェンコ大将

- 第12航空軍

- 騎兵・機械化群:司令官イッサ・プリーエフ。ソビエト・モンゴル合同部隊

- 太平洋艦隊:司令官イワン・ユマシェフ大将。巡洋艦×2隻、嚮導艦×1隻、駆逐艦・掃海艇×12隻、潜水艦×78隻。兵員11万人。航空機1,549機

- アムール小艦隊:司令官ニコライ・アントノフ少将

兵員1,577,725人、火砲26,137門(迫撃砲含む)、戦車・自走砲5,556両、航空機3,446機を装備(海軍の装備を考慮しない数)。

日本軍[編集]

関東軍[編集]

関東軍は満州防衛の為、ソ連との国境に14の永久要塞を建設していた。

- 東寧要塞…アジア最大の地下要塞。東寧重砲兵連隊が配置された。

- 綏芬河要塞

- 半截河要塞

- 虎頭要塞…シベリア鉄道を視認する戦略上の要衝にあり、東西約10km・南北約4kmの規模を誇る。試製四十一糎榴弾砲、九〇式二十四糎列車加農を筆頭に大口径長射程重砲が配備された。

- 霍爾莫津要塞

- 璦琿要塞

- 黒河要塞

- 海拉爾要塞…ハイラル市を取り囲むように、周囲の山に陣地が築かれ、最大3万人が収容できる大陸屈指の要塞であった。西部防衛の要

- 五家子要塞

- 鹿鳴台要塞

- 観月台要塞

- 廟嶺要塞

- 法別拉要塞

- 鳳翔要塞

関東軍の作戦構想とは、要塞群の密集する東部・北部に主力部隊を配置してソ連軍を阻止し、西方面では逐次的な抗戦と段階的な後退行動によって敵部隊を消耗させつつ連京線以東の山岳地帯に誘導して、ここで敵主力を可能な限り叩き、最終的には通化・臨江を中心とする総複郭内に立て篭もる[6]。

また満州各地で広く遊撃戦を行い、できる限りソ連軍の戦力を破砕する。ただし一部の前進を阻止遅滞させるための玉砕的な戦闘も予想しうる。後退の際には適時交通要所や重要施設は破壊して、敵の行動を妨害する、というものだった。日本軍は満州の地形を最大限に利用し防衛計画を立てた[6]。

満州の農業と工業の大半は平野部に集中し、三方から囲む山岳と森林が天然の要害となっていた[6]。特に西部の大興安嶺は標高900メートルに達し、わずかな峠道も湿地帯で覆われ、機械化兵力の通行に適していなかった[6]。

全部隊兵力の比率は日満軍1に対して、赤軍は1.15であり単純な兵員数に大きな差はなかった[6]。ただ戦車と砲の数はソ連が圧倒的であり、日本軍を満州の天然の要害を活かして、兵器面での劣勢を相殺した[6]。西部が通行不能な地形なため、日本軍は東部、北部、北西の鉄道沿線と国境要塞線に戦力を集中し、第1方面軍だけが縦深的防御態勢をとっていた。

西部の海拉爾要塞が純粋な防衛拠点なのにたいし、東部の虎頭・綏芬河・東寧要塞は反撃用の攻勢拠点としての機能も有していた。東部の三要塞には砲兵部隊が重点的に配置され、虎頭・綏芬河・東寧のラインが主力決戦用の攻勢拠点として整備された。鹿鳴台・五家子・観月台要塞は間隙部の防衛とソ連軍の攻勢を阻止し日本軍の反撃を支援する攻防両面の機能を兼ね備えていた。

西部正面の海拉爾要塞は東部での反撃が完了するまで西部のソ連軍攻勢を抑止することが求められた。北部・西部は東部での決戦が完了するまで守勢に徹し、東部での作戦が完了次第、撤退を開始、ソ連軍主力を山岳部に誘導し東部の日本軍主力と合流した上で撃破作戦に移行する。日本軍の要塞陣地は単純な防御施設にとどまらず、敵を効果的に分断、撃破する機動戦用の戦略拠点として機能した。

戦術理論として一定の合理性を持つ作戦であったものの、当時の情勢と関東軍の準備状況などからは遊撃戦の展開や段階的な後退は非常に実行が困難な作戦であった。西正面のソ連軍の機甲部隊に対しては、第44軍(3個師団基幹)と第108師団を配備したに過ぎず、またこれらの部隊も火力・機動力ともに機甲部隊に対しては不足しており、実戦では各個撃破される危険性が高かった。

また関東軍は、戦力の差を縮めるためにゲリラ戦を重視していたが、これは現実的に難しく、困難であった。東部正面においては、元来工事の準備が遅れており、陣地防御もままならない状況であった。通信網でさえ第一線の部隊と司令部間であっても通じておらず、第一方面軍司令部と第五軍司令部の通信は、8月14日になってからであった。

第五方面軍[編集]

第88師団(樺太)においては、対米戦に対応していた時期から、第88師団は樺太を真逢と久春内を結ぶ線で二分、それぞれで自活しつつ来攻する敵の殲滅にあたることとし、やむをえない場合に持久戦に移ることとし、同時に北海道との連絡維持を任務としていた。北部では八方山の陣地を軸とし、その西方山地や東方の軍道(東軍道または栗山道)沿いに北上、侵攻軍の翼に反撃、ツンドラ地帯内か西方山地に圧迫撃滅を図るものであり、南部では上陸阻止を第一としていた。

目標が対ソ戦に切り替わると、以北で小林大佐指揮下の歩兵第125連隊が八方山の複郭陣地などを活用し持久戦にあたり、南進阻止を企図するとした。以南の地域では東半部を歩兵第306連隊西半部に歩兵第25連隊をおき、師団主力は国境ソ連軍の邀撃にはあたらないとする旨が伝えられた。また、豊原地区司令部により、1945年3月25・26日には邦人7688名を地区特設警備隊要員として召集、教育しており、住民を利用したゲリラ戦をも想定していたともいえる。

第91師団(北千島)においては、他の島嶼と同じく北千島においても水際直接配備が当初は主であったが、戦訓から持久戦による出血強要へと方針が転換された。しかし陣地構築の困難さから、砲兵については水際に重点が置かれた。極力水際で打撃を与えつつ、神出鬼没の奇襲で前進を遅滞させるという村上大隊の戦闘計画に掲げられた任務は、その好例といえよう。全体の布陣は二転三転したが、最終的には幌筵海峡重視の配備となっていた。防御に徹した教育訓練がなされたことや、徹底した自給自足により栄養不良患者をほとんど出さなかったのも特徴である。

戦闘序列[編集]

関東軍総司令官 山田乙三 大将(14期)

兵員約70万(詳細な個別師団・部隊の兵員数は不明)、火砲約1,000門(歩兵砲・山砲などすべてを含む)、戦車約200両、航空機約350機(うち戦闘機は65機。練習機なども含む)

第五方面軍 樋口季一郎 中将

居留民への措置[編集]

関東軍と居留民には密接な関連があり、関東軍は居留民の措置について作戦立案上検討している。交通連絡線・生産・補給などに大きく関東軍に貢献していた開拓団は、およそ132万人と考えられていた。開戦の危険性が高まり、関東軍では居留民を内地へ移動させることが検討されたが、輸送のための船舶を用意することは事実上不可能であり、朝鮮半島に移動させるとしても、いずれ米ソ両軍の上陸によって戦場となるであろう朝鮮半島に送っても仕方がないと考えられ、また輸送に必要な食料も目途が立たなかった。それでも、関東軍総司令部兵站班長・山口敏寿中佐は、老幼婦女や開拓団を国境沿いの放棄地区から抵抗地区後方に引き上げさせることを総司令部第一課(作戦)に提議したが、第一課は居留民の引き上げにより関東軍の後退戦術がソ連側に暴露される可能性があり、ひいてはソ連進攻の誘い水になる恐れがあるとして、「対ソ静謐(せいひつ)保持」を理由に却下している。[要出典]

状況悪化にともない、満州開拓総局は開拓団に対する非常措置を地方に連絡していたが、多くの居留民、開拓団は悪化していく状況を深刻にとらえていなかった[10]。

また満州開拓総局長斉藤中将は開拓団を後退させないと決めていた。加えて事態が深刻化してから東京の中央省庁から在満居留民に対して後退についての考えが示されることもなかった。関東軍の任務として在外邦人保護は重要な任務であったが、「対ソ静謐保持」を理由に国境付近の開拓団を避難させることもなかった。[要出典]

ソ連侵攻時、引き揚げ命令が出ても、一部の開拓総局と開拓団が軍隊の後退守勢を理解せず、待避をよしとしなかった。この判断については、当時の多くの開拓団と開拓総局の人々の、無敵と謳われた関東軍に対する過度の信頼と情報の不足が大きな要因であると考えられる[11]。

8月9日ソ連軍との戦闘が始まると直ちに大本営に報告し、命令を待った。命令が下されたのは翌日10日で、10日9時40分に総参謀長統裁のもとに官民軍の関係者を集め、具体的な居留民待避の検討を開始した。同日18時に民・官・軍の順序で新京駅から列車を出すことを決定し、正午に官民の実行を要求した。しかし官民両方ともに14時になっても避難準備が行われることはなく、軍は1時間の無駄もできない状況を鑑みて、結局民・官・軍を順序とする避難の構想を破棄し、とにかく集まった順番で列車編成を組まざるを得なかった。第1列車が新京を出発したのは予定より大きく遅れた11日1時40分であり、その後総司令部は2時間毎の運行を予定し、大陸鉄道司令部に対して食料補給などの避難措置に必要な対策を指示した。現場では混乱が続き、故障・渋滞・遅滞・事故が続発したために避難措置は非常に困難を極めた。結果として最初に避難したのは、軍家族、満鉄関係者などとなり、暗黙として国境付近の居留民は置き去りにされた。[要出典]

これらに加えて辺境における居留民については、第一線の部隊が保護に努めていたが、ソ連軍との戦闘が激しかったために救出の余力がなく、ほとんどの辺境の居留民は後退できなかった。特に国境付近の居留民の多くは、「根こそぎ動員」によって戦闘力を失っており、死に物狂いでの逃避行のなかで戦ったが、侵攻してきたソ連軍や暴徒と化した満州民、匪賊などによる暴行・略奪・虐殺(葛根廟事件など)が相次ぎ[12][13]、ソ連軍の包囲を受けて集団自決した事例や(麻山事件・佐渡開拓団跡事件)、各地に僅かに生き残っていた国境警察隊員・鉄路警護隊員の玉砕が多く発生した。弾薬処分時の爆発に避難民が巻き込まれる東安駅爆破事件も起きた。また第一線から逃れることができた居留民も飢餓・疾患・疲労で多くの人々が途上で生き別れ・脱落することとなり、収容所に送られ、孤児や満州人の妻となる人々も出た。

当時満州国の首都新京だけでも約14万人の日本人市民が居留していたが、8月11日未明から正午までに18本の列車が新京を後にし3万8000人が脱出した。3万8000人の内訳は

- 軍人関係家族 2万0310人

- 大使館関係家族 750人

- 満鉄関係家族 1万6700人

- 民間人家族 240人

この時、列車での軍人家族脱出組みの指揮を取ったのは関東軍総参謀長秦彦三郎夫人であり、またこの一行の中にいた関東軍総司令官山田乙三夫人と供の者はさらに平壌からは飛行機を使い8月18日には無事日本に帰り着いている。[要出典]

当時新京在住で夫が官僚だった藤原ていによる「流れる星は生きている」では、避難の連絡は軍人と官僚のみに出され、藤原てい自身も避難連絡を近所の民間人には告げず、自分達官僚家族の仲間だけで駅に集結し汽車で脱出したと記述している。[要出典]また、辺境に近い北部の牡丹江に居留していたなかにし礼は、避難しようとする民間人が牡丹江駅に殺到する中、軍人とその家族は、民間人の裏をかいて駅から数キロはなれた地点から特別列車を編成し脱出したと証言している。[要出典]

経過[編集]

初動[編集]

宣戦布告は1945年8月8日(モスクワ時間午後5時、日本時間午後11時)、ソ連外務大臣ヴャチェスラフ・モロトフより日本の佐藤尚武駐ソ連特命全権大使に知らされた。事態を知った佐藤は、東京の政府へ連絡しようとした。ヴャチェスラフ・モロトフは暗号を使用して東京へ連絡する事を許可した。そして佐藤はモスクワ中央電信局から日本の外務省本省に打電した。しかし、モスクワ中央電信局は受理したにもかかわらず、日本電信局に送信しなかった[14]。

8月9日午前1時(ハバロフスク時間)に、ソ連軍は対日攻勢作戦を発動した。同じ頃、関東軍総司令部は第5軍司令部からの緊急電話により、敵が攻撃を開始したとの報告を受けた。さらに牡丹江市街が敵の空爆を受けていると報告を受け、さらに午前1時30分ごろに新京郊外の寛城子が空爆を受けた。[要出典]

総司令部は急遽対応に追われ、当時出張中であった総司令官山田乙三大将に変わり、総参謀長が大本営の意図に基づいて作成していた作戦命令を発令、「東正面の敵は攻撃を開始せり。各方面軍・各軍並びに直轄部隊は進入する敵の攻撃を排除しつつ速やかに前面開戦を準備すべし」と伝えた。さらに中央部の命令を待たず、午前6時に「戦時防衛規定」「満州国防衛法」を発動し、「関東軍満ソ蒙国境警備要綱」を破棄した。[要出典]

この攻撃は、関東軍首脳部と作戦課の楽観的観測を裏切るものとなり、前線では準備不十分な状況で敵部隊を迎え撃つこととなったため、積極的反撃ができない状況での戦闘となった。総司令官は出張先の大連でソ連軍進行の報告に接し、急遽司令部付偵察機で帰還して午後1時に司令部に入って、総参謀長が代行した措置を容認した。さらに総司令官は、宮内府に赴いて溥儀皇帝に状況を説明し、満州国政府を臨江に遷都することを勧めた。皇帝溥儀は満州国閣僚らに日本軍への支援を自発的に命じた[15]。

西正面の状況[編集]

ソ連軍ではザバイカル正面軍、関東軍では第3方面軍がこの地域を担当していた。日本軍の9個師団・3個独混旅団・2個独立戦車旅団基幹に対し、ソ連軍は狙撃28個・騎兵5個・戦車2個・自動車化2個の各師団、戦車・機械化旅団等18個という大兵力であった。関東軍の要塞地帯と主力部隊及び国境守備隊は東部・北東正面に重点配置され、西部・北西正面の守りは手薄だった。方面軍主力は、最初から国境のはるか後方にあり、開戦後は新京-奉天地区に兵力を集中しこの方面でソ連軍を迎撃する準備をしていたため、西正面に機械化戦力を重点配置していたソ連軍の一方的な侵攻を許してしまった。逆にソ連軍から見ると日本軍の抵抗を受けることなく順調に進撃した。第6親衛戦車軍はわずか3日で450キロも進撃した。同軍の先鋒はヴォルコフ中将の第9親衛機械化軍団が務めたが、アメリカ製のシャーマン戦車が湿地帯の峠道に足をとられ、第5親衛戦車軍団のT34部隊が代わりに先導役を務めた。第39軍の側面援護の下、第6親衛戦車軍は満州西部から迂回しつつ、鉄道沿線の日本軍を殲滅していった。8月15日までに第6親衛戦車軍は大興安嶺を突破し、第3方面軍の残存部隊を掃討しつつ満州の中央渓谷に突入した。

一方第3方面軍は既存の築城による抵抗を行い、ゲリラ戦を適時に行うことを作戦計画に加えたが、これを実現することは、訓練、遊撃拠点などの点で困難であり、また機甲部隊に抵抗するための火力が全く不十分であった。同方面軍は8月10日朝に方面軍の主力である第30軍を鉄道沿線に集結させて、担当地域に分割し、ゲリラ戦を実施しつつソ連軍を邀撃しつつも、第108師団は後退させることを考えた。このように方面軍総司令部が関東軍の意図に反して部隊を後退させなかったのは、居留民保護を重視することの姿勢であったと後に第3方面軍作戦参謀によって語られている。関東軍総司令部はこの決戦方式で挑めば一度で戦闘力を消耗してしまうと危惧し、不同意であった。ソ連軍の進行が大規模であったため、総司令部は朝鮮半島の防衛を考慮に入れた段階的な後退を行わねばならないことになっていた。前線では苦戦を強いられており、第44軍では8月10日に新京に向かって後退するために8月12日に本格的に後退行動を開始し、西正面から進行したソ連の主力である第6親衛戦車軍は各所で日本軍と遭遇してこれを破砕、撃破していた。ソ連軍の機甲部隊に対して第2航空軍(原田宇一郎中将)がひとり立ち向かい12日からは連日攻撃に向かった。攻撃機の中には全弾打ち尽くした後、敵戦車群に体当たり攻撃を行ったものは相当数に上った。ソ連進攻当時国境線に布陣していたのは第107師団で、ソ連第39軍の猛攻を一手に引き受けることとなった。師団主力が迎撃態勢をとっていた最中、第44軍から、新京付近に後退せよとの命令を受け、12日から撤退を開始するも既に退路は遮断されていた。ソ連軍に包囲された第107師団は北部の山岳地帯で持久戦闘を展開、終戦を知ることもなく包囲下で健闘を続け、8月25日からは南下した第221狙撃師団と遭遇、このソ連軍を撃退した。関東軍参謀2名の命令により停戦したのは29日のことであった。ソ連・モンゴル軍は外蒙古から内蒙古へと侵攻し、多倫・張家口へと進撃、関東軍と支那派遣軍の連絡線を遮断した。ザバイカル正面軍は西方から関東軍総司令部の置かれた新京へと猛進撃し、8月15日には間近にまで迫り北東部・東部で奮戦する関東軍の連絡線を断ちつつあった。

東正面の状況[編集]

東方面においては日本軍は第1方面軍が、ソ連軍は第1極東正面軍が担当していた。日本軍の10個師団と独立混成旅団・国境守備隊・機動旅団各1個に対し、ソ連軍は35個師団と17個戦車・機械化旅団基幹であった。日本の第1方面軍は、国境の既存防御陣地を保守し、ソ連軍の主力部隊が進行した後は後方からゲリラ戦を以って奇襲を加える防勢作戦を計画していた。牡丹江以北約600キロに第5軍(清水規矩中将)、南部に第3軍(村上啓作中将)を配置、同方面軍の任務は、侵攻する敵の破砕であったが、二次的なものとして、満州国と朝鮮半島の交通路の防衛、方面軍左翼の後退行動の支援があった。

しかし、日本軍の各部隊の人員や装備には深刻な欠員と欠数があり、特に陣地防御に必要な定数を割り込んでいた。同方面軍の主力部隊の一つであった第5軍を例に挙げれば、牡丹江沿岸、東京城から横道河子の線において敵を拒否する任務を担っていたが、銃剣・軍刀・弾薬・燃料だけでなく、火器・火砲にも欠数が多く、銃・軽機関銃、擲弾筒は定数の三分の一から三分の二程度しかなく、また火砲は第124師団、第135師団ともに定数の三分の二以下、第124師団は野砲の欠数を山砲を混ぜて配備し、第135師団は旧式騎砲、迫撃砲で野砲の欠数を補填しているほどであった。

一方メレツコフが指揮する第1極東正面軍は日本軍の強固な要塞地帯の攻略を担当し、最も困難な任務を抱えていた。メレツコフは奇襲を成功させるため、通常の準備砲撃を省略し、雷雨の中偵察大隊を越境させた。30分後には歩兵部隊が日本軍の陣地に浸透し、機械化兵力の前進路を切り開いた。各狙撃師団は傘下の戦車旅団を解き放ち、各戦車旅団は1日で満州領内22キロの地点に到達、日本軍の要塞は迂回し後続の部隊に排除を任せた。実際の戦闘においては第二十五軍、第三十五軍団を主力部隊とする極東方面軍の激しい攻撃を受けることになった。天長山・観月臺の守備隊は敵に包囲され、天長山守備隊は15日に全滅、観月臺は10日に陥落した。また八面通正面では秋皮溝守備隊は9日に全滅、十文字峠・梨山・青狐嶺廟の守備隊も10日にソ連軍の圧倒的な攻撃を受けて陥落、残存した一部の部隊は後退した。平陽付近では、前方に展開していた警備隊がソ連軍の攻撃で全滅し、残りの守備隊は8月9日に夜半撤退したが、10日にソ連軍と遭遇戦が発生し、離脱したのは850人中200人であった。このように各地で抵抗を試みるもその戦力差から悉くが撃破・殲滅されてしまい、ソ連軍の攻撃を遅滞させることはできても、阻止することはできなかった。

東部正面最大都市、牡丹江にソ連軍主力が向かうものと正しく判断した清水司令官は、第124師団、その後方に第126・第135師団を配置、全力を集中してソ連軍侵攻を阻止するよう処置した。ソ連第5軍司令官クルイロフ大将は増強した戦車旅団を牡丹江に差し向け、さらに2個狙撃師団を出撃させた。 穆稜を守備する第124師団(椎名正健中将)の一部は12日に突破されたが、後続のソ連軍部隊と激戦を続け、肉薄攻撃などの必死の攻撃を展開、第126、第135師団主力とともに15日夕までソ連軍の侵攻を阻止し、この間に牡丹江在留邦人約6万人の後退を完了することができた。牡丹江には戦車旅団に先導された4個狙撃師団が殺到し、2日に渡る壮絶な市街戦の末、日本軍5個歩兵連隊が全滅した。牡丹江東側陣地の防御が限界に達した第5軍は、17日までに60キロ西方に後退、そこで停戦命令を受けた。南部の第3軍は、一部の国境配置部隊のほか主力は後方配置していた。8月16日には牡丹江市が陥落した。 一方この正面に進攻したソ連軍第25軍は、北鮮の港湾と満州との連絡遮断を目的としていた。羅子溝の第128師団(水原義重中将)、琿春の第112師団(中村次喜蔵中将)は其々予定の陣地で激戦を展開、多数の死傷者を出しながら停戦までソ連軍大兵力を阻止した。広い地域に分散孤立した状態で攻撃を受けた第3軍は、よく善戦して各地で死闘を繰り広げたが停戦時の17日にはソ連軍が第2線陣地に迫っていた。

北正面の状況[編集]

満州国の北部国境地域、孫呉方面及びハイラル方面でも日本軍(第4軍)は抵抗を試みるもソ連軍の物量を背景にした攻撃で後退を余儀なくされていた。孫呉正面においては、ソ連軍は36軍・39軍・53軍・17軍及びソ蒙連合機動軍を以って8月9日に機甲部隊を先遣隊として攻撃を行ったが、当時の天候が雨であったために沿岸地区の地形が泥濘となって機甲部隊の機動力を奪ったため、作戦は当初遅滞した。日本軍は第123師団と独立混成第135旅団で陣地防御を準備していたが、第2極東方面軍の第2赤衛軍が11日から攻撃を開始した。ソ連軍の攻撃によって一部の陣地が占領されるも、残存した陣地を活用して反撃を行い、抵抗を試みていた。しかし兵力の差から後方に迂回されてしまい、防衛隊は離脱した。またハイラル正面においては、ソ連軍はザバイカル方面軍の最左翼を担当する第36軍の部隊が進行し、日本軍は第119師団と独立混成第80旅団によって抵抗を試み、極力ハイラルの陣地で抵抗しながらも、戦況が悪化すれば後退することが指示されていた。第119師団は停戦するまでソ連軍の突破を阻止し、戦闘ではソ連軍の正面からの攻撃だけでなく、南北の近接地域から別働隊が侵攻してきたために後退行動を行った。

北朝鮮の状況[編集]

北朝鮮においては第34軍(主力部隊は第59師団、第137師団「根こそぎ動員」師団、独立混成第133旅団)が6月18日に関東軍の隷下に入り、7月に咸興に集結した。戦力は第59師団以外は非常に低水準であり、兵站補給も滞っていた。開戦して第17方面軍は関東軍総司令官の指揮下に、第34軍は第17方面軍司令官の指揮下に入った。また羅南師管区部隊は本土決戦の一環として4月20日に編成された部隊であり、2個歩兵補充隊と、5個警備大隊、特設警備大隊8個、高射砲中隊3個、工兵隊3個などから構成されていた。

第一線の状況として、ソ連軍の侵攻は部分的なものであった。咸興方面では第34軍はソ連軍に対して平壌への侵攻を阻止し、朝鮮半島を防衛する目的で配備され、野戦築城を準備していた。しかし終戦までソ連軍との交戦はなかった。一方で羅南方面では、ソ連軍の太平洋艦隊北朝鮮作戦部隊・第一極東方面軍第25軍・第10機甲軍団の一部が来襲した。12日から13日にかけて、ソ連軍は海路から北朝鮮の雄基と羅南に上陸してきた。8月13日にソ連軍の偵察隊が清津に上陸し、その日の正午に攻撃前進を開始した。羅南師管区部隊は上陸部隊の準備が整わないうちに撃滅する作戦を立案し、ソ連軍に対抗して出撃し、上陸したソ連軍を分断、ソ連軍の攻撃前進を阻止するだけの損害を与えることに成功し、水際まで追い詰めたが、14日払暁まで清津に圧迫し、ソ連軍の侵攻を阻止する中15日には新たにソ連第13海兵旅団が上陸、北方から狙撃師団が接近したので決戦を断念し、防御に転じた時に8月18日に停戦命令を受領した。

南樺太および千島の概況[編集]

当時日本が領有していた南樺太・千島列島は、アメリカ軍の西部アリューシャン列島への反攻激化ゆえ急速強化が進んだ。1940年12月以来同地区を含めた北部軍管区を管轄してきた北部軍を、1943年2月5日には北方軍として改編、翌年には第五方面軍を編成し、千島方面防衛にあたる第27軍を新設、第1飛行師団と共にその隷下においた。 結果、1944年秋には千島に5個師団、樺太に1個旅団を擁するに至る。

しかし、本土決戦に向けて戦力の抽出が始まると航空戦力を中心に兵力が転用され、1945年3月27日に編成を完了した第88師団(樺太)や第89師団(南千島)が加わったものの、航空兵力は貧弱なままで、北海道内とあわせ80機程度にとどまっていた。

他方、ソ連軍は同方面を支作戦と位置づけており、その行動は偵察行動にとどまっていた。1945年8月10日22時、第2極東戦線第16軍は「8月11日10:00を期して樺太国境を越境し、北太平洋艦隊と連携して8月25日までに南樺太を占領せよ」との命令を受領、ようやく戦端を開く。しかし、準備時間が限定されており、かつ日本軍の情報が不足していたこともあり、各兵科部隊には具体的な任務を示すには至らなかった。情報不足は深刻で、例えば、樺太の日本軍は戦車を保有しなかったにもかかわらず、第79狙撃師団に対戦車予備が新設されたほどであった。北千島においてはさらに遅れ、8月15日にようやく作戦準備及び実施を内示、8月25日までに北千島の占守島、幌筵島、温禰古丹島を占領するように命じた。

南樺太の戦闘[編集]

樺太の日本軍は、1941年の関東軍特種演習から対ソ戦準備をしていたが、太平洋戦争中盤からは対米戦準備も進められて、中途半端な状態だった。第88師団が主戦力で、うち歩兵第125連隊が国境方面にあった。対ソ開戦後は、特設警備隊の防衛召集や国民義勇戦闘隊の義勇召集が実施され、陣地構築や避難誘導を中心に活動した。居留民については、1944年秋から第5方面軍の避難指示があったが、資材不足などで進んでいなかった。ソ連軍侵攻後に第88師団と樺太庁長官、豊原海軍武官府の協力で、23日までに87670名が離島できた。その後の自力脱出者を合わせても、開戦時住民約41万人のうち約10万人が脱出できたにすぎない[16]。 なお、戦後の引揚者は軍人・軍属2万人、市民28万人の合計30万人で、残留した朝鮮系住民2万7千人を除くと陸上戦の民間人死者は約2,000人と推定されている。後述の引揚船での犠牲者を合わせると、約3,700人に達する[17]。

樺太におけるソ連軍最初の攻撃は、8月9日7時30分武意加の国境警察に加えられた砲撃である。11日5時頃から樺太方面における主力とされたソ連軍第56狙撃軍団は本格的に侵攻を開始した。樺太中央部を通る半田経由のものと、安別を通る西海岸ルートの2方向から侵入した。他方、日本軍は9日に方面軍の出した「積極戦闘を禁ず」という命令のため、専守防御的なものとなった。後にこの命令は解除されたが前線には届かなかった。日本軍は、国境付近の半田10kmほど後方の八方山陣地において陣地防御を実施した。日本の第5方面軍は航空支援や増援作戦等を計画したが、8月15日に中止となった。

戦闘は8月15日以降も継続し、むしろ拡大していった。日本政府からの明確な指示が出ないまま、ソ連軍による無差別攻撃に対応し日本軍も自衛戦闘として応戦を続けた。16日には塔路・恵須取へソ連軍が上陸作戦を実施。20日には真岡へも上陸し、この際に逃げ場を失った電話交換女子達が集団自決する真岡郵便電信局事件が発生した。真岡の歩兵第25連隊は、ソ連軍による軍使殺害事件が発生したため自衛戦闘に移った。熊笹峠へ後退しつつ抵抗を続け、23日2時ごろまでソ連軍を拘束していた。

8月22日に知取にて停戦協定が結ばれるが、赤十字のテントが張られ白旗が掲げられた豊原駅前にソ連軍航空機による空爆が加えられ多数の死傷者が出た。同日朝には樺太からの引揚船「小笠原丸」「第二号新興丸」「泰東丸」が留萌沖でソ連軍潜水艦に攻撃され、1708名の死者と行方不明者を出した(三船殉難事件)。

その後もソ連軍は南下を継続し24日早朝には豊原に到達、樺太庁の業務を停止させて日本軍の施設を接収した。25日には大泊に上陸、樺太全土を占領した。

千島列島の状況と戦闘[編集]

アリューシャン列島からの撤退により、千島列島、中でも占守島をはじめとする北千島が脚光をあびる。当初はアッツ島からの空爆に対する防空戦が主であったが、米軍の反攻に伴い、兵力増強が図られる。本土決戦に備えて抽出がなされたのは樺太と同様であるが、北千島はその補給の困難から、ある程度の数が終戦まで確保(第91師団基幹の兵力約25000人、火砲約200門)された。防衛計画は、対米戦における戦訓から、水際直接配備から持久抵抗を志向するようになったが、陣地構築の問題から砲兵は水際配備とする変則的な布陣となっていた。

8月9日からのソ連対日参戦後も特に動きはないまま、8月15日を迎えた。方面軍からの18日16時を期限とする戦闘停止命令を受け、兵器の逐次処分等が始まっていた。だが、ソ連軍は15日に千島列島北部の占守島への侵攻を決め、太平洋艦隊司令長官ユマシェフ海軍大将と第二極東方面軍司令官プルカエフ上級大将に作戦準備と実施を明示していた。

18日未明、ソ連軍は揚陸艇16隻、艦艇38隻、上陸部隊8363人、航空機78機による上陸作戦を開始した。投入されたのは第101狙撃師団(欠第302狙撃連隊)とペトロパヴロフスク海軍基地の全艦艇など、第128混成飛行師団などであった。日本軍第91師団は、このソ連軍に対して水際で火力防御を行い、少なくともソ連軍の艦艇13隻を沈没させる戦果を上げている。

上陸に成功したソ連軍部隊が、島北部の四嶺山付近で日本軍1個大隊と激戦となった。日本軍は戦車第11連隊などを出撃させて反撃を行い、戦車多数を失いながらもソ連軍を後退させた。しかし、ソ連軍も再攻撃を開始し激しい戦闘が続いた。18日午後には、日本軍は歩兵73旅団隷下の各大隊などの配置を終え有利な態勢であったが、日本政府の意向を受け第5方面軍司令官 樋口季一郎中将の命令に従い、第91師団は16時に戦闘行動の停止命令を発した。停戦交渉の間も小競り合いが続いたが、21日に最終的な停戦が実現し、23・24日にわたり日本軍の武装解除がなされた。

それ以降、ソ連軍は25日に松輪島、31日に得撫島という順に、守備隊の降伏を受け入れながら各島を順次占領していった。南千島占領も別部隊により進められ、8月29日に択捉島、9月1日〜4日に国後島・色丹島の占領を完了した。歯舞群島の占領は、降伏文書調印後の、3日から5日のことである[1][2]。

ポツダム宣言受諾後の戦闘[編集]

外地での戦闘が完全に収束する前に、1945年(昭和20年)8月14日、日本政府はポツダム宣言を受諾し、翌8月15日、終戦詔書が発布された。8月16日、大本営は大陸令第一三八二号により陸軍全部隊に対し「即時戦闘行動を停止スヘシ」と命じたが「止ムヲ得サル自衛ノ為ノ戦闘行動ハ之ヲ妨ケス」と自衛戦闘については除外した[18][19]。その後、大本営は停戦命令を段階的に「強化」し、25日に自衛戦闘を含む一切の戦闘行為を禁止した[5]。樺太では23日、千島では25日までに戦闘が停止したが、満洲では命令伝達の困難から8月末まで戦闘が継続した[5]。ソ連は日本と連合国が降伏文書への調印を行った9月2日の後も作戦を継続し、9月5日、ソ連軍は一方的な戦闘攻撃をようやく停止した[20][5]。

ソ連最高統帥部は「日本政府の宣言受諾は政治的な意向である。その証拠には軍事行動には何ら変化もなく、現に日本軍には停戦の兆候を認め得ない」との見解を表明し、攻勢作戦を続行した。この為、日本軍は戦闘行動にて防衛対応する他なかった。[要出典]

連合国最高司令官ダグラス・マッカーサー元帥は8月15日に、昭和天皇・政府・大本営以下、日本軍全てに対する戦闘停止を命じた。この通達に基づき、8月16日、関東軍に対しても自衛以外の戦闘行動を停止するように命令が出された。しかし、当時の関東軍の指揮下にあった部隊のほぼすべてが、激しい攻撃を仕掛けるソ連軍に抵抗していたため、全く状況は変わらなかった。すでに17の要塞地区のうち16が陥落し指揮系統は分断され関東軍は危機的状況にあった。[要出典]

8月17日、関東軍総司令官山田乙三大将がソ連側と交渉に入ったものの、極東ソ連軍総司令官ヴァシレフスキー元帥は、8月20日午前まで停戦しないと回答した。関東軍とソ連軍の停戦が急務となったマッカーサーは8月18日に改めて、日本軍全部隊のあらゆる武力行動を停止する命令を出し、これを受けた日本軍は各地で戦闘を停止し、停戦が本格化することとなった。その同日、ヴァシレフスキーは、2個狙撃師団に北海道上陸命令を下達していたが、樺太方面の進撃の停滞とスタフカからの命令により実行されることはなかった。[要出典]

8月19日の15:30(極東時間)、関東軍総参謀長秦彦三郎中将は、ソ連側の要求を全て受け入れ、本格的な停戦・武装解除が始まった。これを受け、8月24日にはスタフカから正式な停戦命令がソ連軍に届いたが、ソ連軍による作戦は1945年9月2日の日本との降伏文書調印をも無視して継続された。結局ソ連軍は、満洲、朝鮮半島北部、南樺太、北千島、択捉、国後、色丹、歯舞の全域を完全に支配下に置いた9月5日になってようやく、一方的な戦闘攻撃を終了した[1][2]。

前線部隊の状況[編集]

対ソ防衛戦は満州国各地、及び朝鮮半島北部などにおいて広範に行われた。全体的には日本軍が終始戦力格差から見て各地で一日の間に陣地を突破される事態が各地で発生し、突破された部隊は南方への抽出を受けて全体的に戦力が低下しており戦況を立て直すことができず、いとも簡単に前線陣地を突破され逃げることがほとんどであった。北正面・東正面に戦力を集中していた関東軍は西正面に投入されたソ連軍の機械化戦力を阻止できず内陸部への進撃をゆるしてしまった。関東軍が主力を集中した北部・東部でも濃密な火力支援をえたソ連軍の機動により、国境要塞群は分断・包囲され次々と無力化され破壊されていった。国境要塞は基本的に関東軍が想定していた 効果を発揮できなかった。各国境要塞は開戦後間もなく制圧され、五家子要塞にいたってはわずか半日で陥落した。虎頭・東寧要塞はもちこたえたが国境要塞陣地の壊滅は、関東軍の反撃計画を瓦解させた。

しかし、編成が終了したばかりの新兵と不十分な装備という弱い部隊を、強大なソ連軍が進撃してくる戦場正面に投入したが、交戦前に混乱状態に陥った部隊は皆無であった。例えば第5軍は、絶望的な戦力格差があるソ連軍と交戦し、少なからぬ被害を受けたものの、1個師団を用いて後衛とし、2個師団を後方に組織的に離脱させ、しかも陣地を新設して邀撃(ようげき)の準備を行い、さらに自軍陣地の後方に各部隊を新たに再編して予備兵力となる予備野戦戦力を準備することにも成功している。このことから、非常に優れた指揮の下で円滑に後退戦が行われたことがうかがえる。

また既存陣地(永久陣地及び強固な野戦陣地)に配備された警備隊は、ほぼ全てが現地の固守を命じられていた。これは後方に第2、第3の予備陣地が構築されておらず、また増援が見込めない為である。そのため後退できない日本軍の警備隊は、圧倒的な物量作戦で波状攻撃をかけるソ連軍に対して各地で悲愴な陣地防御戦を行い、そのほとんどが担当地域で壊滅することになった[21]。

在留邦人の状況[編集]

満洲の兵力の大半は南方へ移転、昭和20年春からの「根こそぎ動員」により壮年男子が召集されていたので、開拓団には老人、女性、子供ばかりが残され、僻地の開拓団にはソ連参戦も日本敗戦も伝わらなかった[13]。また、日ソ開戦前に関東軍が主力を北朝鮮方面に後退させたので、ソ満国境附近の日本人開拓移民は戦場に取り残され、混乱の中で多数の犠牲者や孤児が出ることになった[5]。大半の開拓移民や居留民は荷馬車に荷を積み徒歩で都市部に向かう途上、ソ連軍や現地の暴徒の襲撃を受け、戦死あるいは自決、病死、栄養失調死も多かった[13]。

ソ連軍首脳部は日本軍と日本人に対する非人道的な行為を戒めていたが、ソ連軍の現地部隊はそれを無視しており、正当な理由のない発砲・略奪・強姦・車両奪取などが堂々と行われていた。また推定50万人の避難民が発生し、飢餓と寒さで衰弱していった。関東軍は当時、武装解除が行われており、具体的な対応手段は完全に封殺され失われていた。このような中で、ソ連軍から支配地を引き継いだ八路軍による圧政から通化事件のような虐殺事件が起きた[要出典]。

ソ連軍は開拓団で退避した人々の群れを見ると、機銃掃射を浴びせた。それでも逃げる在留邦人を、今度は中国人農民が匪賊となって襲撃し、虐殺して死者の衣服まで奪い取って行った。8月14日に起きた葛根廟事件では、数千人の避難民が退避している際にソ連軍から一斉射撃を浴びた後、戦車に轢き殺された者もあり、女性将校に指示されキビ畑の空地に集められた母子約30人にソ連兵が銃を撃ちまくって全滅させる場面もあった[12]。生き残った子供も暴民に拉致され売り飛ばされるなどした[22]。

その後生存者も死者も中国の暴民によって衣服をはがされ、強姦された。また吉林省扶余県の開拓団の事例では、親しかった中国人が暴徒襲撃の情報を教えてくれたので、竹槍などで武装して戦ったが、中国人暴徒の数は2000人にも及び、婦女子以下自決して272名が死んだという[23]。そのほか、敦化事件、牡丹江事件、麻山事件などが起こった。

このような逼迫した状況下で関東軍の現地責任者は、一刻も早くこの現状下に鑑み現地での状況を東京に逐次伝え、ソ連に対してこのような事態を一刻も早く改善するようにと外交的交渉を早く進展するようにと求めることが限界であった。この時点で本来なら関東軍を指揮督戦して励ます筈の上層部はすでに航空機等で本土にいち早く退避しており、満州国に残された現地の責任者等は、このような現地状況を日本政府に電報を使用して再三に渡って送り続けた。一方日本政府は連絡船などによる内地向け乗船に満州からの避難民を優先するようにと本土より打電をして取り計らっていた。[要出典]

このとき内地に戻ることができず現地に留まった在留邦人は中国残留日本人と呼ばれており、日中両国の政府やNPOによる日本への帰国や帰国後の支援などにより問題の解決が図られているが、終戦から70年がたった後でも完全な解決には至っていないのが現状である。また、樺太では在樺コリアンの問題が残っている。

関東州を含めた在満洲日本人居留民は155万~160万人、その約14%にあたる27万人が開拓民であり、うち7万8500人が死亡した。これは日本人死亡者17万6千人の45%にあたる[13][12]。

題材とした作品[編集]

- 本作品の第四部と第五部はソ連対日参戦を描いている。

- 『満州帝国崩壊 〜ソビエト進軍1945〜』

- 監督:ユーリ・イヴァンチュク

- 出演:ヴァレンチナ・グルシナ, ヤナ・ドラズ、ヴィクトル・ネズナノフほか

- 1982年・ソビエト、87分・カラー

- 満州への侵攻を赤軍の視点で描いた作品。T-34-85など当時の兵器も実物が登場する。ただし、日本軍の描写には不自然な点が多い。

- 『樺太1945年夏 氷雪の門』

- 1974年・日本、終戦後も電話交換作業を続けるために留まった女性交換手が、ソ連軍が迫る中自決した真岡郵便電信局事件を描いた作品。なお、公開時にモスクワ放送が名指しで「非友好的な作品」と批判するなど、国際問題になった。

- 『大地の子』

- 1987年〜1991年・日本、山崎豊子原作の小説・テレビドラマ。冒頭、ソ連参戦により関東軍と共に逃避行を繰り広げる満蒙開拓団が、ソ連軍に虐殺されるシーンがある。

- 『霧の火 樺太・真岡郵便局に散った九人の乙女たち』

- 2008年・日本、日本テレビ製作の単発ドラマ。真岡郵便電信局事件を描いた作品。

脚注[編集]

- ^ a b c , http://hoppou-gifu.jp/history/history.html#06+2012年10月30日閲覧。

- ^ a b c , オリジナルの2014年9月7日時点におけるアーカイブ。, https://web.archive.org/web/20140907215243/http://www.hoppou.go.jp/gakushu/outline/history/history6/+2012年10月30日閲覧。

- ^ "August Storm: The Soviet 1945 Strategic Offensive in Manchuria. Leavenworth Papers No.7. by LTC David. M. Glantz" Combat Studies Institute, fort Leavenworth, Kansas, 1983

- ^ Cherevko, Kirill Evgen'evich (2003). Serp i Molot protiv Samurayskogo Mecha. Moscow: Veche. ISBN 5-94538-328-7. Page 41

- ^ a b c d e 山田朗「ソ連の対日参戦」吉田裕・森武麿・伊香俊哉・高岡裕之編『アジア・太平洋戦争辞典』吉川弘文館、二〇一五年十一月十日 第一版第一刷発行、ISBN 978-4-642-01473-1、362~363頁。

- ^ a b c d e f g 戦術・戦略分析 詳解 独ソ戦全史「史上最大の地上戦」の実像 デビット・M・グランツ ジョナサン・M・ハウス共著 守屋純訳 p567

- ^ a b c d e f g 戦術・戦略分析 詳解 独ソ戦全史「史上最大の地上戦」の実像 デビット・M・グランツ ジョナサン・M・ハウス共著 守屋純訳 p570

- ^ “ソ連の北方四島占領、米が援助 極秘に艦船貸与し訓練も”. 北海道新聞 (2017年12月30日). 2018年9月2日閲覧。

- ^ 越田稜編著「アジアの教科書に書かれた日本の戦争 東アジア編」梨の木舎、1990年

- ^ 角田房子『墓標なき八万の死者 ― 満蒙開拓団の壊滅』(中央公論新社)P105

- ^ 角田房子『墓標なき八万の死者 ― 満蒙開拓団の壊滅』(中央公論新社)P75

- ^ a b c 秦郁彦「日本開拓民と葛根廟の惨劇 (満州)」秦郁彦・佐瀬昌盛・常石敬一編『世界戦争犯罪事典』文藝春秋、2002年8月10日 第1刷、ISBN 4-16-358560-5、260~261頁。

- ^ a b c d 坂部晶子「開拓民の受難」貴志俊彦・松重充浩・松村史紀編『二〇世紀満洲歴史事典』吉川弘文館、二〇一二年 (平成二十四年) 十二月十日 第一刷発行、ISBN 978-4-642-01469-4、543頁。

- ^ 対日宣戦布告時、ソ連が公電遮断英極秘文書産経新聞(2015.8.9)web魚拓

- ^ 「ラストエンペラー」溥儀の自伝、完全版が刊行へ 朝日新聞2006年12月17日

- ^ 『北東方面陸軍作戦(2)』、536頁。

- ^ 中山隆志 『一九四五年夏 最後の日ソ戦』 中央公論新社〈中公文庫〉、2001年、179頁。

- ^ 山田朗「日本の敗戦と大本営命令」駿台史学会編『駿台史学』第94号、1995 年3 月、145頁。

- ^ 井口治夫・松田康博「日本の復興と国共内戦・朝鮮戦争」川島真・服部龍二編『東アジア国際政治史』名古屋大学出版会、2007年6月10日 初版第1刷発行、ISBN 978-4-8158-0561-6、216頁。

- ^ 服部倫卓「日ロ関係を左右しかねないロシアが第二次大戦終結記念日を1日ずらした理由」『朝日新聞GLOBE+』2020-05-05

- ^ 防衛庁防衛研修所戦史室『戦史叢書 関東軍 <2> 関特演・終戦時の対ソ戦』朝雲新聞社(昭和49年6月28日発行)

- ^ 鈴木貞美『満洲国 交錯するナショナリズム <平凡社新書 967>』平凡社、2021年2月15日 初版第1刷、ISBN 978-4-582-85967-8、304頁。

- ^ 拳骨拓史『「反日思想」歴史の真実』 [要ページ番号]

参考文献[編集]

- 防衛庁防衛研修所戦史室『戦史叢書 北東方面陸軍作戦 <2> 千島・樺太・北海道の防衛』朝雲新聞社(昭和46年3月31日発行)

- 防衛庁防衛研修所戦史室『戦史叢書 関東軍 <2> 関特演・終戦時の対ソ戦』朝雲新聞社(昭和49年6月28日発行)

- 金子俊男『樺太一九四五年夏 -樺太終戦記録-』(1974年4月28日第4刷)

- 秦郁彦『日本陸海軍総合辞典』東京大学出版会(1996年9月10日第4版)

- 角田房子『墓標なき八万の死者 ― 満蒙開拓団の壊滅』(中央公論新社) ISBN 412200313X

関連項目[編集]

第二次世界大戦

ヤルタ会談

ポツダム宣言

ソ連対日宣戦布告

満州国

関東軍

北方領土

シベリア抑留

日本の降伏

虎頭要塞

小笠原丸

占守島の戦い

葛根廟事件

牡丹江事件

真岡郵便電信局事件

敦化事件

麻山事件

三船殉難事件

プロジェクト・フラ

日本の分割統治計画

外部リンク[編集]

ウィキメディア・コモンズには、ソ連対日参戦に関連するメディアがあります。

ウィキメディア・コモンズには、ソ連対日参戦に関連するメディアがあります。

満州、東満の部隊と抑留記 兵隊三ヶ月 捕虜三年 - ウェイバックマシン(2018年11月5日アーカイブ分)

| ||

Soviet–Japanese War

| Soviet-Japanese War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theater of World War II | |||||||||

US and Soviet sailors and seamen celebrating together on VJ Day | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

Soviet Union:

| Japan:

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

Soviet claim:

| |||||||||

The Soviet–Japanese War (Russian: Советско-японская война; Japanese: ソ連対日参戦, soren tai nichi sansen "Soviet Union entry into war against Japan") was a military conflict within the Second World War beginning soon after midnight on August 9, 1945, with the Soviet invasion of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo. The Soviets and Mongolians ended Japanese control of Manchukuo, Mengjiang (Inner Mongolia), northern Korea, Karafuto, and the Chishima Islands (Kuril Islands). The defeat of Japan's Kwantung Army helped bring about the Japanese surrender and the termination of World War II.[9][10] The Soviet entry into the war was a significant factor in the Japanese government's decision to surrender unconditionally, as it made apparent that the Soviet Union was not willing to act as a third party in negotiating an end to hostilities on conditional terms.[1][2][11][12][13][14][15][16]

Summary[edit]

At the Tehran Conference in November 1943, Joseph Stalin agreed that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan once Germany was defeated. At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, Stalin agreed to Allied pleas to enter World War II in the Pacific Theater within three months of the end of the war in Europe. On July 26, the US, the UK, and China made the Potsdam Declaration, an ultimatum calling for the Japanese surrender that if ignored would lead to their "prompt and utter destruction".

The commencement of the invasion fell between the US atomic bombings of Hiroshima on August 6 and Nagasaki on August 9. Although Stalin had been told virtually nothing of the US and UK's atomic bomb program by Allied governments, the date of the invasion was foreshadowed by the Yalta agreement, the date of the German surrender, and the fact that, on August 3, Marshal Vasilevsky reported to Stalin that, if necessary, he could attack on the morning of August 5. The timing was well-planned and enabled the Soviet Union to enter the Pacific Theater on the side of the Allies, as previously agreed, before the war's end.[17] The invasion of the second largest Japanese island of Hokkaido, originally planned by the Soviets to be part of the territory taken,[18] was held off due to apprehension of the US' new position as an atomic power.[19][20][21][22]

At 11 pm Trans-Baikal time on August 8, 1945, Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov informed Japanese ambassador Naotake Satō that the Soviet Union had declared war on Japan, and that from August 9 the Soviet Government would consider itself to be at war with Japan.[23] At one minute past midnight Trans-Baikal time on August 9, 1945, the Soviets commenced their invasion simultaneously on three fronts to the east, west and north of Manchuria. The operation was subdivided into smaller operational and tactical parts:

- Khingan–Mukden Offensive Operation (August 9, 1945 – September 2, 1945)

- Harbin–Kirin Offensive Operation (August 9, 1945 – September 2, 1945)

- Sungari Offensive Operation (August 9, 1945 – September 2, 1945)

and subsequently

- South Sakhalin Operation (August 11, 1945 – August 25, 1945)

- Soviet assault on Maoka (August 19, 1945 - August 22, 1945)

- Seishin Landing Operation (August 13, 1945 – August 16, 1945)

- Kuril Landing Operation (August 18, 1945 – September 1, 1945)

Though the battle extended beyond the borders traditionally known as Manchuria – that is, the traditional lands of the Manchus – the coordinated and integrated invasions of Japan's northern territories has also been called the Battle of Manchuria.[24] Since 1983, the operation has sometimes been called Operation August Storm, after American Army historian Lieutenant-Colonel David Glantz used this title for a paper on the subject.[1] It has also been referred to by its Soviet name, the Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation, but this name refers more to the Soviet invasion of Manchuria than to the whole war.

This offensive should not be confused with the Soviet–Japanese Border Wars (particularly the Battle of Khalkhin Gol/Nomonhan Incident of May–September 1939), that ended in Japan's defeat in 1939, and led to the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact.[25]

Background and buildup[edit]

The Russo-Japanese War of the early 20th century resulted in a Japanese victory and the Treaty of Portsmouth by which, in conjunction with other later events including the Mukden Incident and Japanese invasion of Manchuria in September 1931, Japan eventually gained control of Korea, Manchuria and South Sakhalin. In the late 1930s were a number of Soviet-Japanese border incidents, the most significant being the Battle of Lake Khasan (Changkufeng Incident, July–August 1938) and the Battle of Khalkhin Gol (Nomonhan Incident, May–September 1939), which led to the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact[25][26] of April 1941. The Neutrality Pact freed up forces from the border incidents and enabled the Soviets to concentrate on their war with Germany and the Japanese to concentrate on their southern expansion into Asia and the Pacific Ocean.

With success at the Battle of Stalingrad and the eventual defeat of Germany becoming increasingly certain, the Soviet attitude to Japan changed, both publicly, with Stalin making speeches denouncing Japan, and privately, with the Soviets building up forces and supplies in the Far East. At the Tehran Conference (November 1943), Stalin, Winston Churchill, and Franklin Roosevelt agreed that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan once Germany was defeated. Stalin faced a dilemma since he wanted to avoid a two-front war at almost any cost but also wanted to extract gains in the Far East as well as Europe. The only way that Stalin could make Far Eastern gains without a two-front war would be for Germany to surrender before Japan.

The Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact caused the Soviets to make it policy to intern Allied aircrews who landed in Soviet territory after operations against Japan, but airmen held in the Soviet Union under such circumstances were usually allowed to "escape" after some period of time.[27] Nevertheless, even before the defeat of Germany, the Soviet buildup in the Far East had steadily accelerated. By early 1945, it had become apparent to the Japanese that the Soviets were preparing to invade Manchuria, but they were unlikely to attack prior to Germany's defeat. In addition to their problems in the Pacific, the Japanese realised that they needed to determine when and where a Soviet invasion would occur.

At the Yalta Conference (February 1945), Stalin secured from Roosevelt the promise of Stalin's Far Eastern territorial desires in return for agreeing to enter the Pacific War within two or three months of the defeat of Germany. By mid-March 1945, things were not going well in the Pacific for the Japanese, who withdrew their elite troops from Manchuria to support actions in the Pacific. Meanwhile, the Soviets continued their Far Eastern buildup. The Soviets had decided that they did not wish to renew the Neutrality Pact. The Neutrality Pact required that twelve months before its expiry, the Soviets must advise the Japanese and so on April 5, 1945, they informed the Japanese that they did not wish to renew the treaty.[28] That caused the Japanese considerable concern,[29][30] but the Soviets went to great efforts to assure the Japanese that the treaty would still be in force for another twelve months and that the Japanese had nothing to worry about.[31]

On May 9, 1945 (Moscow Time), Germany surrendered and so if the Soviets were to honour the Yalta Agreement, they would need to enter war with Japan by August 9, 1945. The situation continued to deteriorate for the Japanese, now the only Axis power left in the war. They were keen to remain at peace with the Soviets and extend the Neutrality Pact[31] and also wanted to achieve an end to the war. Since Yalta, they had repeatedly approached or tried to approach the Soviets to extend the Neutrality Pact and to enlist the Soviets in negotiating peace with the Allies. The Soviets did nothing to discourage the Japanese hopes and drew the process out as long as possible but continued to prepare their invasion forces.[31] One of the roles of the Cabinet of Admiral Baron Suzuki, which took office in April 1945, was to try to secure any peace terms short of unconditional surrender.[32] In late June, they approached the Soviets (the Neutrality Pact was still in place), inviting them to negotiate peace with the Allies in support of Japan, providing them with specific proposals and in return, they offered the Soviets very attractive territorial concessions. Stalin expressed interest, and the Japanese awaited the Soviet response. The Soviets continued to avoid providing a response. The Potsdam Conference was held from July 16 to August 2, 1945. On July 24, the Soviet Union recalled all embassy staff and families from Japan. On July 26, the conference produced the Potsdam Declaration whereby Churchill, Harry S. Truman and Chiang Kai-shek (the Soviet Union was not officially at war with Japan) demanded the unconditional surrender of Japan. The Japanese continued to wait for the Soviet response and avoided responding to the declaration.[31]

The Japanese had been monitoring Trans-Siberian Railway traffic and Soviet activity to the east of Manchuria and the Soviet delaying tactics, which suggested to them that the Soviets would not be ready to invade east Manchuria before the end of August. They did not have any real idea and no confirming evidence as to when or where any invasion would occur.[12] They had estimated that an attack was not likely in August 1945 or before spring 1946, but Stavka had planned for a mid-August 1945 offensive and had concealed the buildup of a force of 90 divisions. Many had crossed Siberia in their vehicles to avoid straining the rail link.[33]

The Japanese were caught completely by surprise when the Soviets declared war an hour before midnight on 8 August 1945 and invaded simultaneously on three fronts just after midnight on 9 August.[citation needed]

Combatant forces[edit]

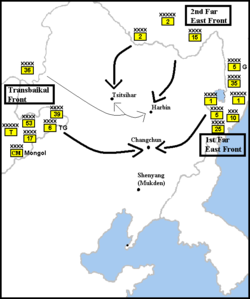

Soviets[edit]

The Far East Command,[2] under Marshal of the Soviet Union Aleksandr Vasilevsky, had a plan for the conquest of Manchuria that was simple but huge in scale[1] by calling for a massive pincer movement over all of Manchuria. The pincer movement was to be performed by the Transbaikal Front from the west and by the 1st Far East Front from the east. The 2nd Far East Front was to attack the center of the pocket from the north.[2] The only Soviet equivalent of a theater command that operated during the war (apart from the shortlived 1941 "Directions" in the west), Far East Command, consisted of three Red Army fronts.

Each Front had "front units" attached directly to the front, instead of an army.[1] The forces totaled 89 divisions with 1.5 million men, 3,704 tanks, 1,852 self propelled guns, 85,819 vehicles and 3,721 aircraft. One third of its strength was in combat support and services.[1] Its naval forces contained 12 major surface combatants, 78 submarines, numerous amphibious craft, and the Amur River flotilla, consisting of gunboats and numerous small craft.[1] The Soviet plan incorporated all the experience in maneuver warfare that the Soviets had acquired fighting the Germans, and also used new improved weapons, such as the RPD light machine gun, the new main battle tank T-44 and a small number of JS-3 heavy tanks.[1]

Western Front of Manchuria[edit]

The Transbaikal Front, under Marshal Rodion Malinovsky, was to form the western half of the Soviet pincer movement and to attack across the Inner Mongolian desert and over the Greater Khingan mountains.[2] These forces had the objective to secure Mukden (now Shenyang), then meet troops of the 1st Far East Front at the Changchun area in south-central Manchuria[1] and so end the double envelopment.[1]

Eastern Front of Manchuria[edit]

The 1st Far East Front, under Marshal Kirill Meretskov, was to form the eastern half of the pincer movement. The attack involved striking towards Mudanjiang (or Mutanchiang),[1] and once that city was captured, the force was to advance towards the cities of Jilin (or Kirin), Changchun, and Harbin.[1] Its final objective was to link up with forces of the Trans-Baikal Front at Changchun and Jilin (or Kirin) thus closing the double envelopment movement.

As a secondary objective, the 1st Far East Front was to prevent Japanese forces from escaping to Korea and to then invade the Korean Peninsula up to the 38th parallel,[1] establishing in the process what later became North Korea.

Northern Front of Manchuria[edit]

The 2nd Far East Front, under General Purkayev, was in a supporting attack role.[1] Its objectives were the cities of Harbin and Tsitsihar[2] and the prevention of an orderly withdrawal to the south by Japanese forces.[1]

Once troops from the 1st Far East Front and Trans-Baikal Front had captured the city of Changchun, the 2nd Far East Front was to attack the Liaotung Peninsula and seize Port Arthur (present day Lüshun).[1]

Japanese[edit]

The Kwantung Army of the Imperial Japanese Army, under General Otozō Yamada, was the major part of the Japanese occupation forces in Manchuria and Korea and consisted of two Area Armies: the First Area Army (northeastern Manchukuo) and the Third Area Army (southwestern Manchukuo), as well as three independent armies (responsible for northern Manchuria, North Korea, Mengjiang, South Sakhalin, and the Kurils).[1]

Each area army (Homen Gun, the equivalent of a Western "army") had headquarters units and units attached directly to it, in addition to the field armies (the equivalent of a Western corps). In addition was the 40,000-strong Manchukuo Defense Force, composed of eight weak, poorly-equipped, and poorly-trained Manchukuoan divisions.

The Kwantung Army had less than eight hundred thousand (800,000) men in 25 divisions (including two tank divisions) and six Independent Mixed Brigades, which contained over 1,215 armored vehicles (mostly armored cars and light tanks), 6,700 artillery pieces (mostly light), and 1,800 aircraft (mostly trainers and obsolete types). The Imperial Japanese Navy did not contribute to the defense of Manchuria, the occupation of which it had always opposed on strategic grounds. Additionally, by the time of the invasion, the few remnants of its fleet were stationed and tasked with the defense of the Japanese home islands from a possible invasion by Allied forces.

On economic grounds, Manchuria was worth defending since it had the bulk of usable industry and raw materials outside Japan and was still under Japanese control in 1945. The Kwantung Army was far below its authorized strength. Most of its heavy military equipment and all of its best military units had been transferred to the Pacific Front over the previous three years to contend with the advance of American and Allied forces. By 1945, the Kwantung Army contained a large number of raw recruits and conscripts, generally with obsolete, light, or otherwise-limited equipment. As a result, it had essentially been reduced to a light infantry counterinsurgency force with limited mobility or ability to fight a conventional land war against a co-ordinated enemy.

Compounding the problem, the Japanese military made many wrong assumptions and major mistakes, the two most significant the following:

- They wrongly assumed that any attack coming from the west would follow either the old rail line to Hailar or head into Solun from the eastern tip of Mongolia. The Soviets attacked along those routes, but their main attack from the west went through the supposedly-impassable Greater Khingan range south of Solun and into the center of Manchuria.

- Japanese military intelligence failed to determine the nature, location, and scale of the Soviet buildup in the Far East. Based on initial underestimates of Soviet strength and the monitoring of Soviet traffic on the Trans-Siberian Railway, the Japanese believed that the Soviets would not have sufficient forces in place before the end of August and that an attack was most likely in the autumn of 1945 or the spring of 1946.

The withdrawal of the Kwantung Army's elite forces for redeployment into the Pacific Theatre made new operational plans for the defence of Manchuria against a seemingly-inevitable Soviet attack prepared by the Japanese in the summer of 1945. They called for the redeployment of most forces from the border areas, which were to be held lightly with delaying actions. The main force was to hold the southeastern corner in strength to defend Korea from attack.[11]

Furthermore, the Japanese had observed Soviet activity only on the Trans-Siberian Railway and along the East Manchurian front and so prepared for an invasion from the east. They believed that when an attack occurred from the west, their redeployed forces would be able to deal with it.[12][11]

Although the redeployment had been initiated, it was not supposed to be completed until September and so the Kwantung Army was in the process of redeployment when the Soviets launched their attack simultaneously on all three fronts.

Campaign[edit]

The operation was carried out as a classic double pincer movement over an area the size of Western Europe. In the western pincer, the Red Army advanced over the deserts and mountains from Mongolia, far from their resupply railways. That confounded the Japanese military analysis of Soviet logistics, and the defenders were caught by surprise in unfortified positions. The Kwantung Army commanders, involved in a planning exercise at the time of the invasion, were away from their forces for the first 18 hours of conflict. Communication infrastructure was poor, and communication was lost with forward units very early. The Kwantung Army had a formidable reputation as fierce and relentless fighters, and even though weak and unprepared, they put up strong resistance in the town of Hailar, which tied down some of the Soviet forces. At the same time, Soviet airborne units were used to seize airfields and city centers in advance of the land forces and to ferry fuel to the units that had outrun their supply lines. The Soviet pincer from the east crossed the Ussuri and advanced around Khanka Lake and attacked towards Suifenhe. Although Japanese defenders fought hard and provided strong resistance, the Soviets proved to be overwhelming.

After a week of fighting during which Soviet forces had penetrated deep into Manchukuo, Japanese Emperor Hirohito recorded the Gyokuon-hōsō, which was broadcast on radio to the Japanese nation on August 15, 1945. The idea of surrender was incomprehensible to the Japanese people, and combined with Hirohito's use of formal and archaic language, the fact that he did not use the word "surrender", the poor quality of the broadcast, and the poor lines of communication, there was some confusion for the Japanese about what the announcement meant. The Imperial Japanese Army Headquarters did not immediately communicate the ceasefire order to the Kwantung Army, and many elements of the Army either did not understand it or ignored it. Hence, pockets of fierce resistance from the Kwantung Army continued, and the Soviets continued their advance, largely avoiding the pockets of resistance, reaching Mukden, Changchun and Qiqihar by August 20. On the Soviet right flank, the Soviet-Mongolian Cavalry-Mechanized Group had entered Inner Mongolia and quickly took Dolon Nur and Kalgan. The Emperor of Manchukuo and former Emperor of China, Puyi, was captured by the Soviet Red Army. The ceasefire order was eventually communicated to the Kwantung Army but not before the Soviet Union had made most of their territorial gains.

On August 18, several Soviet amphibious landings had been conducted ahead of the land advance: three in northern Korea, one in South Sakhalin, and one in the Chishima Islands. In Korea at least, there were already Soviet soldiers waiting for the troops coming overland. In Karafuto and the Chishimas, that meant a sudden and undeniable establishment of Soviet sovereignty.

On August 10, the US government proposed to the Soviet government to divide the occupation of Korea between them at the 38th parallel north. The Americans were surprised that the Soviet government accepted. Soviet troops were able to move freely by rail, and there was nothing to stop them from occupying the whole of Korea.[34] Soviet forces began amphibious landings in northern Korea by August 14 and rapidly took over the northeast of the peninsula, and on August 16, they landed at Wonsan.[35] On August 24, the Red Army entered Pyongyang and established a military government over Korea north of the 38th parallel. American forces landed at Incheon on September 8 and took control of the south.[36][37]

Aftermath[edit]

Since the first major Japanese military defeats in the Pacific in the summer of 1942, the civilian leaders of Japan had come to realise that the Japanese military campaign was economically unsustainable, as Japan did not have the industrial capacity to fight the United States, China and the British Empire at the same time, and there were a number of initiatives to negotiate a cessation of hostilities and the consolidation of Japanese territorial and economic gains. Hence, elements of the non-military leadership had first made the decision to surrender as early as 1943. The major issue was the terms and conditions of surrender, not the issue of surrender itself. For a variety of diverse reasons, none of the initiatives was successful, the two major reasons being the Soviet Union's deception and delaying tactics and the attitudes of the "Big Six", the powerful Japanese military leaders.[13]

The Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation, along with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, combined to break the Japanese political deadlock and force the Japanese leaders to accept the terms of surrender demanded by the Allies.

In the "Sixty Years after Hiroshima" issue of The Weekly Standard, the American historian Richard B. Frank points out that there are a number of schools of thought with varying opinions of what caused the Japanese to surrender. He describes what he calls the "traditionalist" view, which asserts that the Japanese surrendered because the Americans dropped the atomic bombs. He goes on summarize other points of view in conflict with the traditionalist view: namely, that the Japanese government saw their situation as hopeless and was already ready to surrender before the atomic bombs - and that the Soviets went to war against Japan.[38]

Tsuyoshi Hasegawa's research has led him to conclude that the atomic bombings were not the principal reason for Japan's capitulation. He argues that Japan's leaders were impacted more by the swift and devastating Soviet victories on the mainland in the week after Joseph Stalin's August 8 declaration of war because the Japanese strategy to protect the home islands was designed to fend off an Allied invasion from the south and left virtually no spare troops to counter a Soviet threat from the north. Furthermore, the Japanese could no longer hope to achieve a negotiated peace with the Allies by using the Soviet Union as a mediator with the Soviet declaration of war. That, according to Hasegawa, amounted to a "strategic bankruptcy" for the Japanese and forced their message of surrender on August 15, 1945.[39][16] Others with similar views include the Battlefield series documentary,[2][11] among others, but all, including Hasegawa, state that the surrender was not caused by only one factor or event.

The Soviet invasion and occupation of the defunct Manchukuo marked the start of a traumatic period for the more than one million residents of the puppet state who were of Japanese descent. The situation for the Japanese military occupants was clear, but the Japanese colonists who had made Manchukuo their home, particularly those born in Manchukuo, were now stateless and homeless, and the (non-Japanese) Manchurians wanted to be rid of these foreigners. Many residents were killed, and others ended up in Siberian prisons for up to 20 years. Some made their way to the Japanese home islands, where they were also treated as foreigners.[32][40][41][42]

Manchuria was "cleansed" by Soviet forces of any potential military resistance. With Soviet support for the spread of communism,[43] Manchuria provided the main base of operations for Mao Zedong's forces, who proved victorious in the following four years of the Chinese Civil War. The military successes in Manchuria and China by the Communist Chinese led to the Soviet Union giving up their rights to bases in China, promised by the Western Allies, because all of the land deemed by the Soviets to be Chinese, as distinct from what the Soviets considered to be Soviet land that had been occupied by the Japanese, was eventually turned over to the People's Republic of China.[43] Before leaving Manchuria, Soviet forces and bureaucracy dismantled almost all of the portable parts of the considerable Japanese-built industry in Manchuria and relocated it to "restore industry in war-torn Soviet territory." What was not portable was either disabled or destroyed since the Soviets had no desire for Manchuria to be an economic rival, particularly to the underdeveloped Far Eastern Soviet Territories.[32] After the establishment of the People's Republic of China, the bulk of the Soviet economic assistance went to Manchuria to help rebuilding the region's industry.[44][full citation needed]

As agreed at Yalta, the Soviet Union had intervened in the war with Japan within three months of the German surrender and so was therefore entitled to annex the territories of South Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands and also to preeminent interests over Port Arthur and Dalian, with its strategic rail connections, via the China Changchun Railway, a company owned jointly by China and the Soviet Union that operated all railways of the former Manchukuo. The territories on the Asian mainland were transferred to the full control of the People's Republic of China in 1955. The other possessions are still administered by the Soviet Union's successor state, Russia. The annexation of South Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands is of great importance as the Sea of Okhotsk became a Soviet inland sea, which continues to have great strategic benefit to Russia.

The division of Korea between the Soviet and US occupations led to the creation of the separate states of North and South Korea, a precursor to the Korean War five years later.[45]

See also[edit]

- Battles of Khalkhin Gol

- Battle of Mutanchiang

- Battle of Shumshu

- Military history of Japan

- Military history of the Soviet Union

- Kuril Islands dispute

- Project Hula

Notes[edit]

- ^ Glantz credits the Japanese with 713,000 men in northern Korea and Manchuria, and 280,000 in southern Korea, South Sakhalin, and the Kuriles.

- ^ 41,199 is the listed total of Japanese soldiers in Soviet custody on August 19, two days after the surrender of the Kwantung Army by order of Hirohito and four days after Hirohito announced the surrender of Japan. Post-war, 594,000 to 609,000 Japanese soldiers ended up in Soviet custody.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r LTC David M. Glantz, "August Storm: The Soviet 1945 Strategic Offensive in Manchuria". Leavenworth Papers No. 7, Combat Studies Institute, February 1983, Fort Leavenworth Kansas.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Battlefield Manchuria – The Forgotten Victory", Battlefield (U.S. TV series), 2001, 98 minutes.

- ^ a b Glantz, David M. & House, Jonathan (1995), When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler, Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, ISBN 0-7006-0899-0, p. 378

- ^ Jowett, p. 53.

- ^ Glantz, David M. & House, Jonathan (1995), When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler, Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, ISBN 0-7006-0899-0, p. 300

- ^ G. F. Krivosheev, ed., "Russia and the USSR in twentieth century wars: A statistical survey". Moscow: Olma-press, 2001, page 309.

- ^ Cherevko, Kirill Evgen'evich (2003). Serp i Molot protiv Samurayskogo Mecha. Moscow: Veche. ISBN 5-94538-328-7. Page 41.

- ^ Coox, Alvin D. (1990) [1985]. Nomonhan: Japan Against Russia, 1939. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 1176. ISBN 9780804718356. Retrieved February 9,2017.

- ^ The Associated Press (August 8, 2005). "A Soviet Push Helped Force Japan to Surrender". The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on December 12, 2013.

- ^ Lekic, Slobodan (August 22, 2010). "How the Soviets helped Allies defeat Japan". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ a b c d Hayashi, S. (1955). Study of Strategic and Tactical peculiarities of Far Eastern Russia and Soviet Far East Forces. Japanese Special Studies on Manchuria (Report). XIII. Tokyo: Military History Section, Headquarters, Army Forces Far East, US Army.

- ^ a b c Drea, E. J. (1984). "Missing Intentions: Japanese Intelligence and the Soviet Invasion of Manchuria, 1945". Military Affairs. 48 (2): 66–73. doi:10.2307/1987650. JSTOR 1987650.

- ^ a b Butow, Robert Joseph Charles (1956). Japan's decision to surrender. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804704601.

- ^ Richard B. Frank, Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire, Penguin, 2001 ISBN 978-0-14-100146-3. (Extracts on-line)

- ^ Robert James Maddox, Hiroshima in History: The Myths of Revisionism, University of Missouri Press, 2007 ISBN 978-0-8262-1732-5.

- ^ a b Tsuyoshi Hasegawa (2006). Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. Belknap Press. p. 298. ISBN 0-674-01693-9.

- ^ Holloway, David. Stalin and the bomb: the Soviet Union and atomic energy, 1939–1956. Yale University Press, 1996. (p. 127–129)

- ^ Archive, Wilson Center Digital. Wilson Center Digital Archive, digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/122335. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/122335

- ^ Archive, Wilson Center Digital. Wilson Center Digital Archive, digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/122330. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/122330

- ^ Archive, Wilson Center Digital. Wilson Center Digital Archive, digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/122340.http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/122333

- ^ Archive, Wilson Center Digital. Wilson Center Digital Archive, digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/122333.http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/122340

- ^ Radchenko, Sergey. "Did Hiroshima Save Japan From Soviet Occupation?" Foreign Policy, September 23, 2015.

- ^ Soviet Declaration of War on Japan, August 8, 1945. (Avalon Project at Yale University)

- ^ Maurer, Herrymon, Collision of East and West, Henry Regnery Company, Chicago, 1951, p.238.

- ^ a b Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact, April 13, 1941. (Avalon Project at Yale University)

- ^ Declaration Regarding Mongolia, April 13, 1941. (Avalon Project at Yale University)

- ^ Goodby, James E; Ivanov, Vladimir I; Shimotomai, Nobuo (1995). "Northern Territories" and Beyond: Russian, Japanese, and American Perspectives. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 36. ISBN 027595093X.

- ^ Soviet Denunciation of the Pact with Japan, April 5, 1945. (Avalon Project at Yale University)

- ^ "So sorry, Mr Sato", April 1945, Time magazine.

- ^ Russia and Japan Archived 2011-09-13 at the Wayback Machine, declassified CIA report from April 1945.

- ^ a b c d Boris Nikolaevich Slavinskiĭ, The Japanese-Soviet Neutrality Pact: A Diplomatic History 1941–1945, Translated by Geoffrey Jukes, 2004, Routledge. (Extracts online)

- ^ a b c Jones, F. C. "Manchuria since 1931", 1949, Royal Institute of International Affairs, London. p.221

- ^ Glantz, David M. (1995). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. Kansas, USA: University Press of Kansas. p. 278. ISBN 0-7006-0899-0.

- ^ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- ^ Seth, Michael J. (2010). A Concise History of Modern Korea: From the Late Nineteenth Century to the Present. Hawaìi studies on Korea. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 86. ISBN 9780742567139. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 50. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ^ Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 18.

- ^ Richard B. Frank (August 8, 2005). "Why Truman Dropped the Bomb". The Weekly Standard. 010 (44). Archived from the original on July 31, 2005.

- ^ Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi (August 17, 2007). "The Atomic Bombs and the Soviet Invasion: What Drove Japan's Decision to Surrender?". Japan Focus.

- ^ Kuramoto, K. (1990). Manchurian Legacy : Memoirs of a Japanese Colonist. East Lansing, Michigan State University Press.

- ^ Shin'ichi, Y. (2006). Manchuria under Japanese Dominion. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press.

- ^ Tamanoi, M A. (2009). Memory Maps : The State and Manchuria in Postwar Japan. Honolulu, University of Hawai'i Press.

- ^ a b Borisov, O. (1977). The Soviet Union and the Manchurian Revolutionary Base (1945–1949). Moscow, Progress Publishers.

- ^ M. V. Aleksandrova (2013). "Economy of Northeastern China and Soviet assistance to the PRC in the 1950s"

- ^ Weathersby, Catherine SOVIET AIMS IN KOREA AND THE ORIGINS OF THE KOREAN WAR, 1945-1950: NEW EVIDENCE FROM RUSSIAN ARCHIVES The Cold War International History Project Working Paper 8, page 10-13 (November 1993). http://pages.ucsd.edu/~bslantchev/courses/nss/documents/weathersby-soviet-aims-in-korea.pdf

Further reading[edit]

- Despres, J, Dzirkals, L, et al. (1976). Timely Lessons of History : The Manchurian Model for Soviet Strategy. Santa Monica, RAND: 103. (available on-line)

- Duara, P. (2006). The New Imperialism and the Post-Colonial Developmental State: Manchukuo in comparative perspective. Japan Focus.

- Garthoff, R L. (1966). Soviet Military Policy : A Historical Analysis. London, Faber and Faber.

- Garthoff, R L. (1969). The Soviet Manchurian Campaign, August 1945. Military Affairs XXXIII(Oct 1969): 312–336.

- Glantz, David M. (1983a). August Storm: The Soviet 1945 Strategic Offensive in Manchuria, Leavenworth Paper No.7, Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, February 1983.

- Glantz, David M. (1983b). August Storm: Soviet Tactical and Operational Combat in Manchuria, 1945, Leavenworth Paper No.8, Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, June 1983.

- Glantz, David M. (1995) The Soviet Invasion of Japan. Quarterly Journal of Military History, vol. 7, no. 3, Spring 1995.

- Glantz, David M. (2003). The Soviet Strategic Offensive in Manchuria, 1945 (Cass Series on Soviet (Russian) Military Experience, 7). Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-5279-2.

- Gordin, Michael D. (2005). Five Days in August: How World War II Became a Nuclear War. (Extracts on-line)

- Hallman, A L. (1995). Battlefield Operational Functions and the Soviet Campaign against Japan in 1945. Quantico, Virginia, United States Marine Corps Command and Staff College. (available on-line)

- Hasegawa, T. (Ed.) (2007). The End of the Pacific War. (Extracts on-line)

- Ishiwatari, H, Mizumachi, K, et al. (1946) No.77 – Japanese Preparations for Operations in Manchuria (prior to 1943). Tokyo, Military History Section, Headquarters, Army Forces Far East, US Army.

- Jowett, Phillip (2005). Rays of the Rising Sun: Japan's Asian Allies 1931–45 Volume 1: China and Manchukuo. Helion and Company Ltd. ISBN 1-874622-21-3.

- Phillips, S. (2004). The Sino-Japanese War, 1937–1945 : The Military Struggle – Research Guide and Bibliography. Towson University. available on-line

- USMCU CSC (1986). The Soviet Army Offensive : Manchuria, 1945. (US Marine Corps University, Command and Staff College – available on-line)

- Walg, A. J. (March–April 1997). "Wings over the Steppe: Aerial Warfare in Mongolia 1930–1945, Part Three". Air Enthusiast. No. 68. pp. 70–73. ISSN 0143-5450.

Japanese Monographs[edit]

The "Japanese Monographs" and the "Japanese Studies on Manchuria" – The 187 Japan Monographs are a series of operational histories written by former officers of the Japanese army and navy under the direction of General Headquarters of the U.S. Far East Command.

- Monographs of particular relevance to Manchuria are:

- No. 77 Japanese preparations for Operations in Manchuria (1931–1942)

- No. 78 The Kwangtung Army in the Manchurian Campaign (1941–1945) Plans and Preparations

- No. 119 Outline of Operations prior to the Termination of War and activities connected with the Cessation of Hostilities (July – August 1945)

- No. 138 Japanese preparations for Operations in Manchuria (January, 1943 – August 1945)

- No. 154 Record of Operations against Soviet Russia, Eastern Front (August 1945)

- No. 155 Record of Operations against Soviet Russia, Northern and Western Fronts (August – September 1945)

- List of the 13 Studies on Manchuria

- Vol. I Japanese Operational Planning against the USSR (1932–1945)

- Vol. II Imperial Japanese Army in Manchuria (1894–1945) Historical Summary

- Vol. III STRATEGIC STUDY ON MANCHURIA MILITARY TOPOGRAPHY AND GEOGRAPHY Terrain Study

- Vol. IV AIR OPERATIONS (1931–1945) Plans and Preparations

- Vol. V INFANTRY OPERATIONS

- Vol. VI ARMOR OPERATIONS

- Vol. VII SUPPORTING ARMS AND SERVICES

- Vol. VIII LOGISTICS IN MANCHURIA

- Vol. IX CLIMATIC FACTORS

- Vol. X Japanese Intelligence Planning against the USSR (1934–1941)

- Vol. XI Small Wars and Border Problems

- Vol. XII Anti-Bandit Operation (1931–1941)

- Vol. XIII Study of Strategic and Tactical peculiarities of Far Eastern Russia and Soviet Eastern Forces (1931–1945)

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Soviet–Japanese War (1945). |

- Japanese Air Order of Battle and Operations Against 'August Storm', August 1945.

- WW2DB: Operation August Storm

- Observations over Soviet Air Arm in Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation:

- Soviet side information:

- Comment over Soviet Pacific Fleet during Russian-German Conflict and Japanese forces actions in this period

- Comment about Soviet Russian Pacific Fleet actions during Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation

- General information over Soviet Invasion to Japanese land in Karafuto and Kuriles from August 1945, with some photos, only in Russian language.

- Soviet battle maps:

- Japanese POWs:

- Operation August Storm photo gallery:

- Japanese in Manchuria and Korea following the war

- Conflicts in 1945

- Pacific theatre of World War II

- Battles of World War II involving Japan

- Battles involving the Soviet Union

- Wars involving Mongolia

- 1940s in Mongolia

- Mongolia–Soviet Union relations

- World War II operations and battles of the Pacific theatre

- Invasions

- Mengjiang

- History of Manchuria

- History of Inner Mongolia

- 1945 in Japan

- Japan–Soviet Union relations

- 1945 in Mongolia

- Wars involving Manchukuo

- Wars involving Japan

- August 1945 events

- September 1945 events

No comments:

Post a Comment