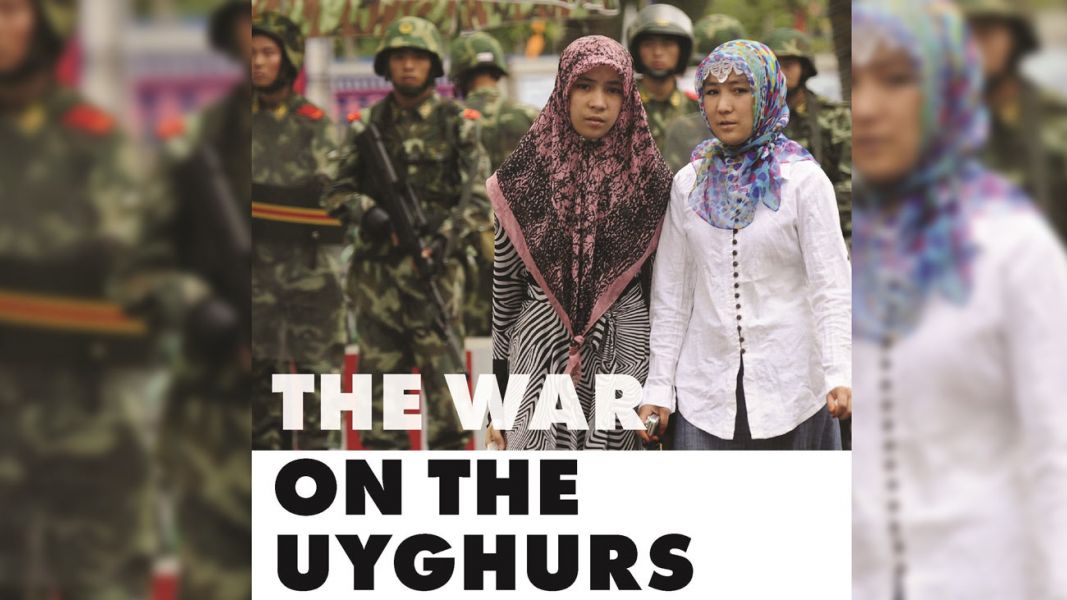

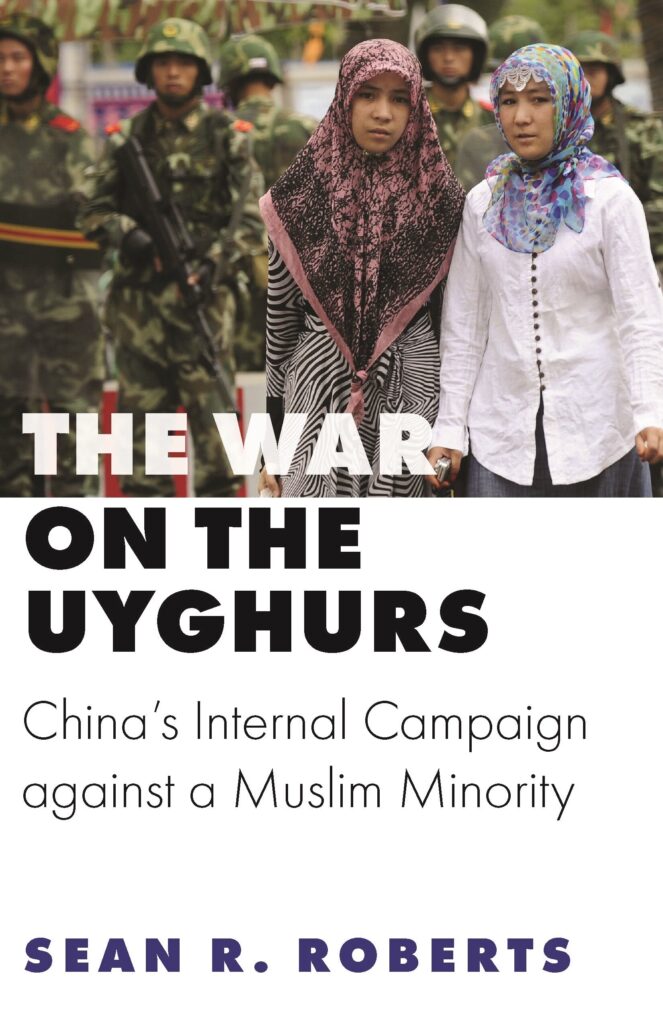

The War on the Uyghurs: A Conversation with Sean R. Roberts

Sean Roberts, an associate professor of international affairs and anthropology at George Washington University, is the author of The War on the Uyghurs: China’s Campaign against Xinjiang Muslims (Manchester University Press and Princeton University Press, 2020), the first book-length treatment of the Chinese state’s campaign against the Uyghur population of Xinjiang. The text situates the campaign as part of a long history of settler colonialism in the region, augmented by the rhetoric surrounding the US-led Global War on Terror (GWOT). Roberts draws on his fieldwork experience, ties with Uyghur communities, extensive documentary research, and training in anthropological theory to narrate and contextualise the actions of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). In his preface, Roberts makes the grim forecast that ‘the ultimate transformation of the Uyghur homeland into a Han-dominated part of the PRC [is] a fait accompli’. As the role of the central leadership in the violent assimilationist campaign becomes clearer, this prediction seems more justified than ever. The discussion below steps back from those human rights concerns, and instead delves into the theories and ideologies that swirl around them.

Matthew P. Robertson: My interest in the topic of your book lies almost as much in the tangle of discourses surrounding it as it does in the actual substance of what is happening in Xinjiang. The concepts at stake—terrorism, ethno-nationalism, indigeneity, settler colonialism, genocide—go to the heart of the political. I have spent a lot of time reading arguments from ‘tankies’, or those who instinctively defend China based on the idea that it is an example of actually existing socialism resisting Western imperialism. They feel they must deny or raise doubts about the PRC’s campaign because attention on the latest atrocity helps China’s enemies and, in their view, enables socialism to be equated with totalitarianism. Some of the most articulate of these are self-consciously Stalinist. How does this happen?

Sean R. Roberts: Ah, yes, the ‘tankies’. I’m mildly obsessed with them as well. They make me start thinking about how people establish broad ideological frameworks that they use to analyse everything around them without attention to local realities, facts, and history. That practice inevitably leads to an irony: adopting contradictory positions while trying to remain ideologically pure. They’re so married to a certain framework that they end up shoving square pegs into round holes. For instance, from a Marxist perspective, I can understand why ‘tankies’ might feel that religion is retrograde, a negative influence on society, and thus not worthy of protection. But on the other hand, when they start using this logic to justify an Islamophobia that is connected to the US-led GWOT, that is puzzling and certainly out of character for self-proclaimed anti-imperialists.

MPR: Because this discourse is associated with US imperialism, so to speak?

SRR: Yes. I have lots of responses on my Twitter timeline where ‘tankies’ post analyses from US neoconservative counterterrorism publications about the Uyghur ‘terrorist threat’ to justify China’s actions against Uyghurs. That is a pretty ironic stance for people who see themselves as committed anti-imperialists. Also, counterterrorism since 9/11 has become an inherently racist ideology, which is connected to colonial discourses of the uncivilised ‘other’. I have a lot of stuff on the cutting-room floor from this book, which I had to write to get my ideas together. I struggled a lot with how and why the GWOT quickly became a racial indictment of Muslims that is prone to genocidal actions. This largely is due to the assumption—inherent in most terrorism analysis—that the reason Jihadists are taking up armed struggle is only because of an irrational ideological adherence to an extremist version of Islam, which negates any grievances they may have, dismisses their voices, and identifies Islam as the motivation for their actions. Yes, Jihadists justify what they’re doing as a part of their religious obligation, but if you look at the people who end up joining these groups, they usually have grievances that are grounded in actual issues and things that have happened to them and their people. ‘Tankies’ and Jihadists share a lot in common: Jihadism or Stalinism presents them with an all-encompassing framework that provides all the answers, and they start framing everything in that way. However, the reasons they choose to find such an all-encompassing ideology to explain the world around them are likely connected to other, more concrete grievances and frustrations they have experienced.

But, to get back to your point about my book engaging lots of concepts that each carry their own baggage and legacy of ideas, this is true. I do this because I see all of these phenomena in what is happening to the Uyghurs in China today, but I also don’t see any one of them being entirely explanatory on their own. In my mind, colonialism represents the most useful explanatory framework, but this becomes a controversial stance because the popular conception of colonialism has become equated with European, and later American, attempts to dominate the world. While Chinese colonialism shares much in common with European and Anglo-American forms of domination over territory and peoples, it does not fit with the rigid Wallersteinian view of a Eurocentric world system that dominates Western leftist thinking about global affairs. This is further complicated by the fact that, contrary to the historical record, the PRC officially refutes that the Uyghur homeland became a part of modern China through conquests in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This lack of recognition of the origins of the Uyghurs’ forcible inclusion in modern China has only perpetuated colonial attitudes towards the Uyghurs and their homeland. Today, what is happening is the logical conclusion of these attitudes as the state is seeking, in the tradition of settler colonialism, to pacify and marginalise the Uyghurs so that it can develop their homeland as part of a Han-centric nation-building project that is fuelled by the state’s economic expansion—not unlike the US colonisation of its west and the pacification and displacement of Native Americans in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Hence, it is a process that inevitably also intersects with questions about indigeneity and of who has the right to determine the future development of this territory.

However, at the same time, these actions are couched in a discourse that is related to the GWOT, which is itself racist and founded in the global inequalities of colonialism. One of the things I try to unpack in my book is how hollow the ideology of counterterrorism has become and how easy it is to manipulate for other purposes. In many ways, it is every bit as narrow as the ideology of the ‘tankies’; both characterise certain actors in the world as inherently evil, almost in a biological or racial way. That said, I try not to overemphasise theoretical arguments about the nature of colonialism and terrorism in the book because it is first and foremost about a human tragedy that requires action, and that is more important than engaging in academic debates about broad conceptual frameworks.

MPR: I benefited from your account of the long history of the colonisation of Xinjiang and the groups—mostly religious—which have risen to resist it. All this makes salient the question of ethno-nationalism and indigeneity as it intersects with the Uyghur cause. Some of the postcolonial literature seems ambivalent about indigeneity because it can be associated with nativism and patriarchy. Ethno-nationalism also does not typically fit comfortably within what we imagine to be the universalist aspirations of liberal democracy, modernity, and individual human rights, etc. Can you please elaborate on the tensions this produces?

SRR: What you’re getting at is one of the inherent contradictions in the postcolonial world. It reminds me of an elderly Uyghur I knew in Kazakhstan in the 1990s, who would always ask: whatever happened to national self-determination? After World War II, self-determination was a central concern as empires were dismantled and newly independent states created, but there’s been an international ambivalence about self-determination as a universal concept ever since because every new nation-state that is recognised chips away at the territory and power of another nation-state. I prefer to view Indigenous peoples as those people in the world who were overlooked in the transition from empires to independent modern nation-states, rather than assigning them some ‘exoticised’ status as the ‘first people’ of a territory. From this perspective, they expose the flaws in the concept of modern nation-states in a postcolonial world. On the one hand, while most modernist ideologies, whether Marxist or capitalist, imagine the withering away of nations as a sort of ‘false consciousness’, history has shown that the implementation of these ideologies does not erase people’s national consciousness. On the other hand, our present world system also shows that the imaginary boundaries of cultural difference represented by nations never completely correspond to the physical borders of states. In this sense, the discourse of indigeneity brings into question both the entire enterprise of modern nation-states and the utopian visions of modernism.

This is the problem with Palestine and Israel, and this is the problem in China with the Uyghur region and Tibet. As national identities without statehood, Palestinian, Uyghur, and Tibetan identities remain deeply connected to a specific territory that they view as their homeland, and this is at odds with the perceptions of the nation-states in which they live. However, I also do not believe this is necessarily a recipe for inevitable conflict. My research on the global Indigenous peoples’ movement and its engagement with development issues suggests an alternative to conflict. Most Indigenous peoples do not view statehood as a realistic option in our system of existing powerful states, but they still want recognition of their unique connection to a specific territory and self-determination over how that territory is developed. Self-determination in this form does not necessarily require separate statehood, but it does require recognition of a people’s collective rights to the decision-making around a specific territory. As such, it is a concept that is at odds with liberal democracy, which imagines all rights as embodied in individuals, and it is also inevitably at odds with global capitalism’s state-centric thirst to exploit territory for economic growth.

I’ve been grappling with this question probably since 2011, when I started teaching a class about Indigenous peoples and development. At the time, I wondered whether the PRC would entertain the idea of recognising Uyghurs as Indigenous people and giving them more of a voice in the development of their homeland. This would actually be in the state’s interest; it would both provide an incentive for Uyghurs to integrate into the Chinese state on their own terms and give the Chinese Government the ability to secure this region that they’re insecure about, albeit without total control over its development and uses. In some ways, this is a system that was at least imagined by the Party in the 1950s when they officially named this region the Uyghur Autonomous Region, but I would argue that the PRC never followed through on giving Uyghurs any real degree of ethnic autonomy in the region.

This has become particularly vivid since the 1990s, when China’s economic expansion fostered a state-led development plan for the Uyghur region that sought to transform it along the lines of development elsewhere in China. Initially, the Chinese state, using modernist thinking borrowed from both Marxism and capitalism, believed that the resultant economic growth and modern amenities would win Uyghurs over, lead to their abandonment of religion and national identity, and end their discontent. However, many Uyghurs viewed this development and the related increasing Han migration to the region as an assault on their cultural uniqueness and connection to a territory they viewed as their homeland, especially in the Uyghur-majority south of the region. This development accelerated significantly in the 2000s and became intertwined with the narrative of the GWOT. In the context of the GWOT, if certain Uyghurs appeared to reject the state-led transformation of their homeland and daily lives, they could now be labelled as ‘terrorists’ or ‘extremists’ and neutralised. In many ways, I would argue that in the context of Xinjiang, the label of ‘terrorist’ became a twenty-first-century version of the US use of ‘savages’ when meeting resistance from Native Americans during the settler colonisation of the American west. Both terms are used to suggest an irrational resistance to what the state views as the inevitable march of progress. In both cases, the result is the destruction of the Indigenous peoples’ identity and social capital, their displacement, and their ultimate marginalisation.

These are some of the reasons that I believe the term ‘indigeneity’ is particularly germane to the Uyghur situation even though Uyghurs have generally not aligned themselves with the global Indigenous peoples’ movement. Most Uyghurs I have encountered over the years have articulated the need for independent statehood, but that is because they feel disenfranchised in their homeland. I believe that if the PRC had given Uyghurs control over the development of their homeland three decades ago, this insistence on statehood would have been replaced with an acceptance of limited sovereignty over their homeland as part of a multinational PRC. Giving Uyghurs such control over the governance of their homeland was perhaps imaginable during the reform period of the 1980s, but today under Xi Jinping’s Party, it is unthinkable. I believe Xi has decided that the Uyghur people are an obstacle to state intentions for their homeland and, thus, must be completely pacified and marginalised like Native Americans in the US west were a century before.

MPR: How much do you see the discourse of terrorism being instrumental to the construction of the supposed Uyghur threat, and how much do you think it has been adopted only opportunistically? If there were no GWOT, would there still be this campaign against the Uyghurs?

SRR: I’m writing a chapter for an edited volume on Islamophobia where I try to unpack this. The interaction between GWOT and what’s happening is complex. When I was writing my book, I realised that the Chinese state sees a certain degree of inevitability in the destruction of the Uyghur people. That’s why I really like David Tobin’s book Securing China’s Northwestern Frontier [Cambridge University Press, 2020]; he unpacks this very opaque baggage on Chinese nation-building, suggesting that Uyghur identity has to be eliminated on various levels in order to create the ideal of the Chinese nation as the Party imagines it. Whether to fulfil the expectations of Marxist theory about the withering away of religion and nationality, to preserve the ideal of 5,000 years of unified Chinese civilisation, to secure this region against perceived separatist claims and outside imperialists, or to prove that Uyghurs have always been part of the Chinese nation, their separate identity must be destroyed. In this context, claims of a Uyghur ‘terrorist threat’ appear to be merely a justification for eliminating these people in the interests of the Chinese nation. However, the logic of ‘terrorism’ as an existential threat to the nation has also been internalised by many Chinese officials and has facilitated a new level of dehumanisation of the Uyghur people.

The GWOT discourse in China seamlessly reinforced pre-existing racist attitudes towards the Uyghurs. The discourse of indigeneity is part of what the Chinese Government is really reacting to; it’s the concept that this region is the Uyghur homeland. That’s a direct challenge to the official state discourse that the region has always been part of China and that Uyghurs have always been Chinese, and it is an obstacle to state intentions for the region. The PRC certainly opportunistically framed its conflict with Uyghurs as a ‘terrorist threat’ immediately after 9/11 to deflect international criticism of its repressive policies in the region. However, I don’t think the PRC necessarily thought it was being disingenuous in doing so because it did not see a difference between ‘terrorism’, ‘extremism’, and ‘separatism’, or the ‘three evils’, as it likes to call them. The Chinese state sees in the GWOT a much older conflict between civilisation and barbarism or savages, and you could argue that this war is perceived by many in the West in the same way. Those characterised as ‘terrorists’ (a term that has no recognised universal definition) are ultimately those who threaten the state’s vision of an orderly society and who happen to be Muslim. They are portrayed as irrational and anti-modern—traits that essentially become characterised as a part of their religion—and they must be defeated in the interests of progress.

Also, as I note in my book, the combined pressures in the region of state-led development and campaigns to identify those harbouring the ‘three evils’ during the first decade after 9/11 eventually spawned acts of violent resistance by Uyghurs. While there is no evidence that most of this violence was actually planned political violence, the state was able to portray it as part of an organised Uyghur ‘terrorist threat’ fuelled by ‘extremist’ beliefs associated with Islam and connected to external influences. As a result, many people, including government officials, began to believe this narrative and to view Uyghurs as an existential ‘terrorist threat’. Furthermore, this led to the creation of China’s own ‘terrorism-industrial complex’ in which people could establish careers by becoming invested in this narrative. In this sense, while the real motivations for what the PRC is doing to Uyghurs have little to do with ‘terrorism’ or ‘extremism’, many involved in the repression as well as many others in China now believe they do. Thus, the narrative of the GWOT has been instrumentally used to justify the erasure of Uyghurs in the same sense that the ‘civilising mission’ was used to justify European colonialism in the nineteenth century. It is not the motivation for the state or empire’s actions, but many implementing or supporting those actions have internalised the idea that it is.

Finally, the logic of the GWOT also helped facilitate the dehumanisation of Uyghurs in a way that was not previously possible. The narrative of the GWOT allowed the Chinese state to locate the source of Uyghurs’ failure to assimilate and their lack of loyalty to a trait within their culture: Islam. While this did not immediately change state attitudes towards Uyghurs on 9/11, it did gradually alter state impressions of their ‘Uyghur problem’. If this problem was related to a global movement of ‘extremist’ Muslims, eliminating the ‘bad apples’ among the population would not resolve it. Rather, the cultural traits of Uyghurs that facilitated the embrace of that ‘extremism’ had to be destroyed. As a result, the state was able to take the leap from suppressing the ‘bad Uyghurs’ to suppressing all Uyghurs and cleansing them of their cultural roots.

MPR: I would like your reaction to a thought experiment I have entertained. It is that the Chinese Communist Party does what they are doing now, but beginning in late 2001, fully leveraging the pervasive panic about terrorism. They stop travel to the region; there is only a small community of scholars studying Uyghurs and Xinjiang; China has been admitted into the World Trade Organization so there is little global appetite for challenging the government; there is no easily accessible satellite imagery; there are barely any data on the internet. It seems conceivable, then, that the entire campaign could have occurred but barely registered in global understanding. The only data would be a paper trail—akin to how the atrocities in the Belgian Congo were first learned about—and many would have been happy to assume that ‘they probably were terrorists’. First, does this thought experiment seem plausible to you? And second, does it give you—as it does me—vertigo to consider it? I mean to suggest the contingency surrounding how we come to learn of a given atrocity ‘as a thing’ in the first place.

SR: On the question of plausibility, it is plausible, but it would not have likely taken place. One of the things I try to demonstrate in my book is that the present situation took time to evolve into an atrocity. While current events emerge from a long and problematic relationship between modern China and the Uyghurs, they needed a perfect storm to turn into the forced erasure of the Uyghurs as we know them. The GWOT was part of that storm, but it also included the urgency that the Party felt in establishing the Belt and Road Initiative, much of which hinges on Xinjiang. It also needed Xi Jinping’s nationalism and desire for societal control, leading the Party to be capable to carry out atrocities, and it needed the state to develop the hubris of a global power to believe it had the right to do so without receiving blowback from the rest of the world.

On the question of the contingency of how we came to learn of what was happening to Uyghurs in China, this is an interesting question. Is an atrocity an atrocity if we do not know about it? However, perhaps even more interesting is the contingency of when this is happening and how that impacts how people feel about it. On the one hand, it is difficult today for states to hide mass atrocities given the power of satellite imagery and the communication abilities facilitated by the internet. On the other hand, these same technologies offer opportunities for scepticism. Are satellite images doctored? Are claims on the internet merely creating disinformation? Furthermore, the internet has created so much information that many people no longer recognise legitimate news sources; both ‘tankies’ and ‘Trumpists’, for example, share a disdain for sources like The New York Times and CNN, referring to them as ‘fake news’. Finally, the fact that people can curate their experience of current events by choosing the news that flows into their timelines means that people have shockingly different interpretations of what is happening in Xinjiang.

Finally, to bring us back full circle to your first question, these factors related to how we consume information are creating more hardened ideological lines around the world that lead people to fit square pegs into round holes. Neoconservatives in the United States have embraced the cause of Uyghurs as a sign of the evil nature of the PRC but happily ignore the role that the GWOT played in facilitating what is happening to them. At the same time, ‘tankies’ support China’s actions against Uyghurs because the PRC represents to them the vanguard of the global socialist revolution, but they happily ignore that these actions are fuelled by racism, colonialism, and the thirst for capital in China. While these perspectives represent ideological extremes, they influence global public opinion about what is happening to Uyghurs on both the right and the left. At the very least, this situation muddies the waters enough to make most people apathetic about the issue.

MPR: On the question of settler colonialism and indigeneity, you argue that countries like the United States and Australia, for example, lack the moral authority to criticise China for what it is doing because of their own settler-colonial pasts. What is the function of moral authority in other states making such critiques? Does any country have the moral authority to criticise the PRC on this?

SRR: Well, moral authority lies in the perception of others. Calls from the United States to protect the rights of Muslims, or to protect the rights of Indigenous peoples, are more easily dismissed by people who may want to dismiss them. It particularly lends itself to ‘whataboutism’ intended to change the subject and raise doubt: ‘How can the United States claim China is committing genocide when the United States committed genocide against the Native Americans?’ This statement, of course, sounds absurd to those people who condemn the actions that have been taken against both Native Americans and Uyghurs, but to those who would prefer to not believe bad things are happening to Uyghurs, it sounds like an appropriate response that vindicates the PRC. This is a strategy often employed by ‘tankies’, but it is increasingly used by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs—sometimes even citing marginalised far-left voices in the United States, Europe, and Australia to make their point. The intention here is to sow doubt and raise the possibility that the US Government has fabricated the atrocities against Uyghurs as a means to stymie China’s rise. If you sow such doubt, the average person who knows nothing about Uyghurs may say: ‘I don’t know. It’s really complicated. Maybe they are terrorists. Maybe the US is making all this up. I don’t know. I’m going to go get a beer.’ The most unfortunate part of this type of discourse is that it makes what is happening to Uyghurs about geopolitical competition between the United States and China, when it should really be about the accountability of powerful states for their actions, whether we are talking about the United States or the PRC.

MPR: Yes, it is this question of doubt I was getting at in the 2001 thought experiment, where the movement for global awareness and response could possibly have been short-circuited—that it wasn’t inevitable that we would learn what we now know. PRC propaganda is important and interesting in this respect. Just for example, did you see the China Daily’s claims that official policies are progressive because they liberate Uyghur women from being ‘baby-making machines’? This is grotesque obviously, but they at least think they are tapping into something that an imagined audience would be receptive to. What is going on there?

SRR: This narrative about the liberation of women is a powerful modernist technique to attack people one wants to portray as ‘uncivilised’. It has long been used by both the Soviet Union and the PRC as a wedge issue against different ethnic groups to justify programs of cultural change, but it has also been used specifically to demonise Muslims by liberals in the United States and Europe—something Muslim feminists often push back against vehemently. This is evident today as the Western media often reduces the many pressing questions arising from the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan to the fate of women’s rights because it creates a visceral response. On the one hand, the rights of women and the power of patriarchal ideas are a real problem everywhere in the world that should be addressed. On the other hand, to portray the exploitation of women as a cultural or religious trait of an entire population of people is a racially profiled indictment of that people. In this particular instance, the PRC seeks to appeal to the Islamophobia of Western liberals. The logic seems to be: the Uyghurs are Muslim, so they must oppress women; maybe this information about forced sterilisations among Uyghur women is really a pro-choice issue about reproductive rights? As with much of the PRC’s propaganda efforts that are produced in English, however, it was explained clumsily and was generally not received by most readers in the way they had hoped.

MPR: What is your sense of the scholarship that is emerging in this field, particularly in political science and international relations? Is there a tension between the ideally value-neutral stance of scholarship, which might bracket its potential impact on victims, and the urgency and reality of what is happening?

SRR: I do see with the empirical turn in social sciences that scholars attempt to detach themselves from the situation on the ground. There were two political scientists I knew in the field during the 1990s; they were giving me a hard time, saying: ‘You’re too close to your subject, you can’t be objective!’ I responded as an anthropologist: ‘You don’t even like this place, why are you doing research here?’ And they said something about how not liking the subject of their research made them more objective. That attitude is found in much of US academia in the social sciences; it’s about making provocative arguments, getting publications in prestigious journals, proving one’s theories, and not being emotionally attached to the subject. This is fine if the goal is merely to build frameworks of knowledge that might help us eventually understand the world better, but it becomes more problematic when it seeks to inform immediate policy that will substantively impact people’s lives. I believe that policy advice should require empathy for the people your recommendations may impact, but this is rarely the case. A particularly obvious example of this is hawkish pundits who frequently call for military responses to problems where such actions will likely result in more misery for those involved while not resolving the problem. It’s particularly problematic to call for the United States to engage China on counterterrorism as a means of ameliorating the situation. This reflects a lack of understanding of what is really motivating the state in the Uyghur region and assumes that US counterterrorism approaches are virtuous, which they are not. Most people intimately aware of the situation in Xinjiang know that US engagement of China on counterterrorism would only make the situation far worse.

No comments:

Post a Comment