Cinema of South Korea

| Cinema of South Korea | |

|---|---|

A movie theater in Seoul | |

| No. of screens | 2,492 (2015)[1] |

| • Per capita | 5.3 per 100,000 (2015)[1] |

| Main distributors | CJ E&M (21%) NEW (18%) Lotte (15%)[2] |

| Produced feature films (2015)[3] | |

| Total | 269 |

| Number of admissions (2015)[4] | |

| Total | 217,300,000 |

| National films | 113,430,600 (52%) |

| Gross box office (2015)[4] | |

| Total | ₩1.59 trillion |

| National films | ₩830 billion (52%) |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Korea |

|---|

| History |

The cinema of South Korea refers to the film industry of South Korea from 1945 to present. South Korean films have been heavily influenced by such events and forces as the Japanese occupation of Korea, the Korean War, government censorship, the business sector, globalization, and the democratization of South Korea.[5][6]

The golden age of South Korean cinema in the mid-20th century produced what are considered two of the best South Korean films of all time, The Housemaid (1960) and Obaltan (1961),[7] while the industry's revival with the Korean New Wave from the late 1990s to the present produced both of the country's highest-grossing films, The Admiral: Roaring Currents (2014) and Extreme Job (2019), as well as prize winners on the festival circuit including Golden Lion recipient Pietà (2012) and Palme d'Or recipient and Academy Award winner Parasite (2019) and international cult classics including Oldboy (2003),[8] Snowpiercer (2013),[9] and Train to Busan (2016).[10]

With the increasing global success and globalization of the Korean film industry, the past two decades have seen Korean actors like Lee Byung-hun and Bae Doona star in American films, Korean auteurs such as Park Chan-wook and Bong Joon-ho direct English-language works, Korean American actors crossover to star in Korean films as with Steven Yeun and Ma Dong-seok, and Korean films be remade in the United States, China, and other markets. The Busan International Film Festival has also grown to become Asia's largest and most important film festival.

American film studios have also set up local subsidiaries like Warner Bros. Korea and 20th Century Fox Korea to finance Korean films like The Age of Shadows (2016) and The Wailing (2016), putting them in direct competition with Korea's Big Four vertically-integrated domestic film production and distribution companies: Lotte Cultureworks (formerly Lotte Entertainment), CJ Entertainment, Next Entertainment World (NEW), and Showbox. Netflix has also entered Korea as a film producer and distributor as part of both its international growth strategy in search of new markets and its drive to find new content for consumers in the U.S. market amid the "streaming wars" with Disney, which has a Korean subsidiary, and other competitors.

History[edit]

Liberation and war (1945-1953)[edit]

With the surrender of Japan in 1945 and the subsequent liberation of Korea, freedom became the predominant theme in South Korean cinema in the late 1940s and early 1950s.[5] One of the most significant films from this era is director Choi In-gyu's Viva Freedom! (1946), which is notable for depicting the Korean independence movement. The film was a major commercial success because it tapped into the public's excitement about the country's recent liberation.[11]

However, during the Korean War, the South Korean film industry stagnated, and only 14 films were produced from 1950 to 1953. All of the films from that era have since been lost.[12] Following the Korean War armistice in 1953, South Korean president Syngman Rhee attempted to rejuvenate the film industry by exempting it from taxation. Additionally foreign aid arrived in the country after the war that provided South Korean filmmakers with equipment and technology to begin producing more films.[13]

Golden age (1955-1972)[edit]

Though filmmakers were still subject to government censorship, South Korea experienced a golden age of cinema, mostly consisting of melodramas, starting in the mid-1950s.[5] The number of films made in South Korea increased from only 15 in 1954 to 111 in 1959.[14]

One of the most popular films of the era, director Lee Kyu-hwan's now lost remake of Chunhyang-jeon (1955), drew 10 percent of Seoul's population to movie theaters[13] However, while Chunhyang-jeon re-told a traditional Korean story, another popular film of the era, Han Hyung-mo's Madame Freedom (1956), told a modern story about female sexuality and Western values.[15]

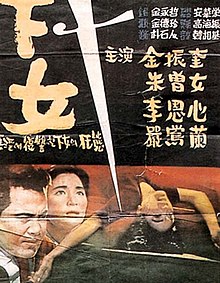

South Korean filmmakers enjoyed a brief freedom from censorship in the early 1960s, between the administrations of Syngman Rhee and Park Chung-hee.[16] Kim Ki-young's The Housemaid (1960) and Yu Hyun-mok's Obaltan (1961), now considered among the best South Korean films ever made, were produced during this time.[7] Kang Dae-jin's The Coachman (1961) became the first South Korean film to win an award at an international film festival when it took home the Silver Bear Jury Prize at the 1961 Berlin International Film Festival.[17][18]

When Park Chung-hee became acting president in 1962, government control over the film industry increased substantially. Under the Motion Picture Law of 1962, a series of increasingly restrictive measures was enacted that limited imported films under a quota system. The new regulations also reduced the number of domestic film-production companies from 71 to 16 within a year. Government censorship targeted obscenity, communism, and unpatriotic themes in films.[19][20] Nonetheless, the Motion Picture Law's limit on imported films resulted in a boom of domestic films. South Korean filmmakers had to work quickly to meet public demand, and many films were shot in only a few weeks. During the 1960s, the most popular South Korean filmmakers released six to eight films per year. Notably, director Kim Soo-yong released ten films in 1967, including Mist, which is considered to be his greatest work.[17]

In 1967, South Korea's first animated feature film, Hong Kil-dong, was released. A handful of animated films followed including Golden Iron Man (1968), South Korea's first science-fiction animated film.[17]

Censorship and propaganda (1973–1979)[edit]

Government control of South Korea's film industry reached its height during the 1970s under President Park Chung-hee's authoritarian "Yusin System." The Korean Motion Picture Promotion Corporation was created in 1973, ostensibly to support and promote the South Korean film industry, but its primary purpose was to control the film industry and promote "politically correct" support for censorship and government ideals.[21] According to the 1981 International Film Guide, "No country has a stricter code of film censorship than South Korea – with the possible exception of the North Koreans and some other Communist bloc countries."[22]

Only filmmakers who had previously produced "ideologically sound" films and who were considered to be loyal to the government were allowed to release new films. Members of the film industry who tried to bypass censorship laws were blacklisted and sometimes imprisoned.[23] One such blacklisted filmmaker, the prolific director Shin Sang-ok, was kidnapped by the North Korean government in 1978 after the South Korean government revoked his film-making license in 1975.[24]

The propaganda-laden movies (or "policy films") produced in the 1970s were unpopular with audiences who had become accustomed to seeing real-life social issues onscreen during the 1950s and 1960s. In addition to government interference, South Korean filmmakers began losing their audience to television, and movie-theater attendance dropped by over 60 percent from 1969 to 1979.[25]

Films that were popular among audiences during this era include Yeong-ja's Heydays (1975) and Winter Woman (1977), both box office hits directed by Kim Ho-sun.[24] Yeong-ja's Heydays and Winter Women are classified as "hostess films," which are movies about prostitutes and bargirls. Despite their overt sexual content, the government allowed the films to be released, and the genre was extremely popular during the 1970s and 1980s.[20]

Recovery (1980–1996)[edit]

In the 1980s, the South Korean government began to relax its censorship and control of the film industry. The Motion Picture Law of 1984 allowed independent filmmakers to begin producing films, and the 1986 revision of the law allowed more films to be imported into South Korea.[19]

Meanwhile, South Korean films began reaching international audiences for the first time in a significant way. Director Im Kwon-taek's Mandala (1981) won the Grand Prix at the 1981 Hawaii Film Festival, and he soon became the first Korean director in years to have his films screened at European film festivals. His film Gilsoddeum (1986) was shown at the 36th Berlin International Film Festival, and actress Kang Soo-yeon won Best Actress at the 1987 Venice International Film Festival for her role in Im's film, The Surrogate Woman.[26]

In 1988, the South Korean government lifted all restrictions on foreign films, and American film companies began to set up offices in South Korea. In order for domestic films to compete, the government once again enforced a screen quota that required movie theaters to show domestic films for at least 146 days per year. However, despite the quota, the market share of domestic films was only 16 percent by 1993.[19]

The South Korean film industry was once again changed in 1992 with Kim Ui-seok's hit film Marriage Story, released by Samsung. It was the first South Korean movie to be released by business conglomerate known as a chaebol, and it paved the way for other chaebols to enter the film industry, using an integrated system of financing, producing, and distributing films.[27]

Renaissance (1997–present)[edit]

As a result of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, many chaebols began to scale back their involvement in the film industry. However, they had already laid the groundwork for a renaissance in South Korean film-making by supporting young directors and introducing good business practices into the industry.[27] "New Korean Cinema," including glossy blockbusters and creative genre films, began to emerge in the late 1990s and 2000s.[6]

South Korean cinema saw domestic box-office success exceeding that of Hollywood films in the late 1990s largely due to screen quota laws that limited the public showing foreign films.[28] First enacted in 1967, South Korea's screen quota placed restrictions on the number of days per year that foreign films could be shown at any given theater—garnering criticism from film distributors outside South Korea as unfair. As a prerequisite for negotiations with the United States for a free-trade agreement, the Korean government cut its annual screen quota for domestic films from 146 days to 73 (allowing more foreign films to enter the market).[29] In February 2006, South Korean movie workers responded to the reduction by staging mass rallies in protest.[30] According to Kim Hyun, "South Korea's movie industry, like that of most countries, is grossly overshadowed by Hollywood. The nation exported US$2 million-worth of movies to the United States last year and imported $35.9 million-worth".[31]

One of the first blockbusters was Kang Je-gyu's Shiri (1999), a film about a North Korean spy in Seoul. It was the first film in South Korean history to sell more than two million tickets in Seoul alone.[32] Shiri was followed by other blockbusters including Park Chan-wook's Joint Security Area (2000), Kwak Jae-yong's My Sassy Girl (2001), Kwak Kyung-taek's Friend (2001), Kang Woo-suk's Silmido (2003), and Kang Je-gyu's Taegukgi (2004). In fact, both Silmido and Taegukgi were seen by 10 million people domestically—about one-quarter of South Korea's entire population.[33]

South Korean films began attracting significant international attention in the 2000s, due in part to filmmaker Park Chan-wook, whose movie Oldboy (2003) won the Grand Prix at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival and was praised by American directors including Quentin Tarantino and Spike Lee, the latter of whom directed the remake Oldboy (2013).[8][34]

Director Bong Joon-ho's The Host (2006) and later the English-language film Snowpiercer (2013), are among the highest-grossing films of all time in South Korea and were praised by foreign film critics.[35][9][36] Yeon Sang-ho's Train to Busan (2016), also one of the highest-grossing films of all time in South Korea, became the second highest-grossing film in Hong Kong in 2016.[37]

In 2019, Bong Joon-ho's Parasite became the first film from South Korea to win the prestigious Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival.[38] At the 92nd Academy Awards, Parasite became the first South Korean film to receive any sort of Academy Awards recognition, receiving six nominations. It won Best Picture, Best Director, Best International Feature Film and Best Original Screenplay, becoming the first film produced entirely by an Asian country to receive a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Picture since Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, as well as the first film not in English ever to win the Oscar for Best Picture.[39]

LGBTQ Cinema[edit]

LGBTQ films and representations of LGBTQ characters in South Korean cinema can be seen since the beginning of South Korean cinema despite public perceptions of South Korea as being largely anti-LGBT. Defining "queer cinema" has been up for debate by critics of cinema because of the difficulties in defining "queer" in film contexts. The term "queer" has its roots in the English language and although its origins held negative connotations, reclamation of the term began in the 1980s in the U.S. and has come to encompass non-heteronormative sexualities even outside of the U.S.[40] Thus, queer cinema in South Korea can be thought of as encompassing depictions of non-heteronormative sexualities. On this note, LGBTQ and queer have been used interchangeably by critics of South Korean cinema.[41] While the characteristics that constitute a film as LGBTQ can be subjective due to defining the term "queer" as well as how explicit or implicit LGBTQ representation is in a film, there are a number of films that have been considered as such in Korean cinema.

According to Pil Ho Kim, Korean queer cinema can be categorized into three different categories regarding visibility and public reception. There is the Invisible Age (1945-1997), where films with queer themes have received limited attention as well as discrete representations due to societal pressures, the Camouflage Age (1998-2004) characterized by a more liberal political and social sphere that encouraged filmmakers to increase production of LGBTQ films and experiment more with their overt depictions but still remaining hesitant, and finally, the Blockbuster Age (2005–present) where LGBTQ themed films began to enter the mainstream following the push against censorship by independent films prior.[42]

Though queer Korean cinema has mainly been represented through independent films and short films, there exists a push for the inclusion of LGBTQ representation in the cinema as well as a call for attention to these films. Turning points include the dismantling of the much stricter Korean Performing Arts Ethics Committee and the emergence of the Korean Council for Performing Arts Promotions and the "Seoul Queer Film and Video Festival" in 1998 after the original gay and lesbian film festival was shut down by Korean authorities.[43] The Korea Queer Film Festival, part of the Korea Queer Culture Festival, has also pushed for visibility of queer Korean films.

LGBTQ films by openly LGBTQ directors[edit]

LGBTQ films by openly LGBTQ identifying directors have historically been released independently, with a majority of them being short films. The films listed reflect such films and reveal how diverse the representations can be.

- Everyday is Like Sunday (Lee Song Hee-il 1997): The independent, short film directed by openly-LGBTQ identifying Lee Hee-il follows two male characters who meet then become separated, with direct representation of their relationship as homosexual. The independent aspect of the film may have had a role in allowing for a more obvious representation of homosexuality since there is less pressure for appealing to a mainstream audience and does not require government sponsorship.[43]

- No Regret (Lee Song Hee-il, 2006): An independent film co-directed by Lee Hee-il and Kim-Cho Kwang-su, both of whom had ties to the gay activist group Ch’in’gusai, portrays LGBTQ characters in a way that normalizes their identities.[42] The film was also able to see more success than usual for independent films for its marketing strategy that targeted a primarily female audience with an interest in what is known as yaoi.[42][44]

- Boy Meets Boy (Kimjo Kwang-soo, 2008): Claimed by the director to be inspired by their own personal experience, the independent short film tells an optimistic story of two men, with the possibility of mutual feelings of attraction after a brief encounter.[45] Even though there is homosexual attraction, it is told through a heterosexual lens, since the masculinity of one character and the femininity of the other are in contrast with each other, creating ambiguity about their queerness due in part to homophobia in society and the political climate.[44]

- Just Friends? (Kimjo Kwang-soo, 2009): This independent short film by Kimjo Kwang-soo, also written as Kim Cho Kwang-soo, represents LGBTQ characters, with the main character, Min-soo, having to deal with his mother’s disapproval of his relationship with another male character. This short film, like Boy Meets Boy also offers a more optimistic ending.[46]

- Stateless Things (Kim Kyung-mook, 2011): In the film, both LGBT characters and Korean-Chinese immigrant workers are considered non-normative and are marginalized.[41] The film can be considered to have a queer point-of-view in the sense that it has an experimental quality that creates ambiguity when it comes to non-normative themes. However, the film does depict graphic, homoeroticism, making the representation of homosexuality clear.[47]

LGBTQ films not by openly LGBTQ directors[edit]

- The Pollen of Flowers (Ha Kil-jong, 1972): Regarded as the first gay Korean film by the director’s brother Ha Myong-jung, the film depicts homosexuality in the film through tension in LGBTQ relationships though it was not typically regarded as a queer film at the time of release.[42] The film's political message and critique of the president at the time, Park Chung-hee, may be the reason that queer relationships were overshadowed.[48] In spite of being an earlier Korean film depicting homosexuality, the film is more explicit in these relationships than might be expected at the time.[48]

- Ascetic: Woman and Woman (Kim Su-hyeong, 1976): Though the film was given award-winning status by the Korean press, during the time of the release, Ascetic remained an under-recognized film by the public.[43] The film is seen as the first lesbian film by Korean magazine Buddy and tells the story of two women who develop feelings for each other.[42] Though the homosexual feelings between the women are implied through “thinly-veiled sex acts” that could be more explicit, it was considered homosexual given the context of the heavy censorship regulations of the 1970s.[42] Despite the film's status as a lesbian film, it has been noted that the director did not intend to make an LGBTQ film, but rather a feminist film by emphasizing the meaningfulness of the two women’s interactions and relationships. Even so, Kim Su-hyeong has said the film can be seen as both lesbian and feminist.[43]

- Road Movie (Kim In-shik, 2002): Even though the film was released through a large distribution company, the film did not reach the expected mainstream box office success, yet it is still seen as a precursor to queer blockbuster films to come.[42] The film is explicit in its homosexual content[44] and portrays a complicated love triangle between two men and a woman while focusing primarily on a character who is homosexual.[44] It is noteworthy that Road Movie is one of the few full-length feature films in South Korea to revolve around a queer main character.[44]

- The King and the Clown (Lee Joon-ik, 2005): The King and the Clown is seen as having a major impact in queer cinema for its great mainstream success. In the film, one of the characters is seen as representing queer-ness through his embodiment of femininity, which is often regarded as the character trope of the “flower boy” or kkonminam.[42] However, actual depictions of homosexuality are limited and are depicted only through a kiss.[42] The King and the Clown is seen as influential because of its representation of suggested gay characters that preceded other queer films to come after it.[44] The film depicts undertones of a love triangle between two jesters and a king and suggests homosexuality in a pre-modern time period (Joseon Dynasty)[44] and is based on the play Yi (2000) which drew on the passage The Annals of the Choseon Dynasty, two pieces that were more explicit in their homosexuality in comparison the film.[44] The representation of gay intimacy and attraction remains ambiguous in the film and has been criticized by the LGBT community for its portrayal of queerness.[44]

- Frozen Flower (Yoo Ha, 2008): A Frozen Flower followed other queer films such as The King and the Clown, Broken Branches, and Road Movie.[41] This film reached a mainstream audience which may have been due in part to a well-received actor playing a homosexual character. Critiques of the film have questioned the character Hong Lim’s homosexuality, however, it may be suggested that his character is actually bisexual.[49] Despite the explicit homosexual/queer love scenes in the film that brought a shock to mainstream audiences,[49] the film still managed to be successful and expose a large audience to a story about queer relationships.[41]

- The Handmaiden (Park Chan-wook, 2016): The film is a cross-cultural adaptation of the lesbian novel Fingersmith written by Sarah Waters.[50] The Handmaiden includes representation of lesbian characters who are seen expressing romantic feelings towards each other in a sensual way that has been critiqued as voyeuristic for its fetishization of the female body.[51] Explicitly depicting the homosexual attraction of the characters Sook-hee and Lady Hideko is a bath scene where the act of filing down the other’s tooth has underlying sexual tension.[51] The film had mainstream box-office success and "over the first six weeks of play [reached a gross] of £1.25 million".[51]

Highest-grossing films[edit]

The Korean Film Council has published box office data on South Korean films since 2004. As of March 2021, the top ten highest-grossing domestic films in South Korea since 2004 are as follows.[35]

- The Admiral: Roaring Currents (2014)

- Extreme Job (2019)

- Along with the Gods: The Two Worlds (2017)

- Ode to My Father (2014)

- Veteran (2015)

- The Thieves (2012)

- Miracle in Cell No.7 (2013)

- Assassination (2015)

- Masquerade (2012)

- Along with the Gods: The Last 49 Days (2018)

Film awards[edit]

South Korea's first film awards ceremonies were established in the 1950s, but have since been discontinued. The longest-running and most popular film awards ceremonies are the Grand Bell Awards, which were established in 1962, and the Blue Dragon Film Awards, which were established in 1963. Other awards ceremonies include the Baeksang Arts Awards, the Korean Association of Film Critics Awards, and the Busan Film Critics Awards.[52]

Film festivals[edit]

In South Korea[edit]

Founded in 1996, the Busan International Film Festival is South Korea's major film festival and has grown to become one of the largest and most prestigious film events in Asia.[53]

South Korea at international festivals[edit]

The first South Korean film to win an award at an international film festival was Kang Dae-jin's The Coachman (1961), which was awarded the Silver Bear Jury Prize at the 1961 Berlin International Film Festival.[17][18] The tables below list South Korean films that have since won major international film festival prizes.

Academy Awards[edit]

| Year | Award | Film | showRecipient[54] |

|---|

Berlin International Film Festival[edit]

| Year | Award | Film | showRecipient[55] |

|---|

Cannes Film Festival[edit]

| Year | Award | Film | showRecipient[56] |

|---|

Venice Film Festival[edit]

| Year | Award | Film | showRecipient[57] |

|---|

Toronto International Film Festival[edit]

| Year | Award | Film | showRecipient[58] |

|---|

Sundance Film Festival[edit]

| Year | Award | Film | showRecipient[59] |

|---|

Telluride Film Festival[edit]

| Year | Award | Film | showRecipient[60] |

|---|

Tokyo International Film Festival[edit]

| Year | Award | Film | showRecipient[61] |

|---|

Locarno Festival[edit]

| Year | Award | Film | showRecipient[62] |

|---|

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Table 8: Cinema Infrastructure - Capacity". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ "Table 6: Share of Top 3 distributors (Excel)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ "Table 1: Feature Film Production - Method of Shooting". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Table 11: Exhibition - Admissions & Gross Box Office (GBO)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Stamatovich, Clinton (25 October 2014). "A Brief History of Korean Cinema, Part One: South Korea by Era". Haps Korea Magazine. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ a b Paquet, Darcy (2012). New Korean Cinema: Breaking the Waves. Columbia University Press. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0231850124..

- ^ a b Min, p.46.

- ^ a b Chee, Alexander (16 October 2017). "Park Chan-wook, the Man Who Put Korean Cinema on the Map". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ a b Nayman, Adam (27 June 2017). "Bong Joon-ho Could Be the New Steven Spielberg". The Ringer. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Jin, Min-ji (13 February 2018). "Third 'Detective K' movie tops the local box office". Korea JoongAng Daily. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ "Viva Freedom! (Jayumanse) (1946)". Korean Film Archive. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Gwon, Yeong-taek (10 August 2013). "한국전쟁 중 제작된 영화의 실체를 마주하다" [Facing the reality of film produced during the Korean War]. Korean Film Archive (in Korean). Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ a b Paquet, Darcy (1 March 2007). "A Short History of Korean Film". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Paquet, Darcy. "1945 to 1959". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ McHugh, Kathleen; Abelmann, Nancy, eds. (2005). South Korean Golden Age Melodrama: Gender, Genre, and National Cinema. Wayne State University Press. pp. 25–38. ISBN 0814332536.

- ^ Goldstein, Rich (30 December 2014). "Propaganda, Protest, and Poisonous Vipers: The Cinema War in Korea". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d Paquet, Darcy. "1960s". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Prizes & Honours 1961". Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Rousse-Marquet, Jennifer (10 July 2013). "The Unique Story of the South Korean Film Industry". French National Audiovisual Institute (INA). Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ a b Kim, Molly Hyo (2016). "Film Censorship Policy During Park Chung Hee's Military Regime (1960-1979) and Hostess Films" (PDF). IAFOR Journal of Cultural Studies. 1 (2): 33–46. doi:10.22492/ijcs.1.2.03 – via wp-content.

- ^ Gateward, Frances (2012). "Korean Cinema after Liberation: Production, Industry, and Regulatory Trend". Seoul Searching: Culture and Identity in Contemporary Korean Cinema. SUNY Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0791479339.

- ^ Kai Hong, "Korea (South)", International Film Guide 1981, p.214. quoted in Armes, Roy (1987). "East and Southeast Asia". Third World Film Making and the West. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 156. ISBN 0-520-05690-6.

- ^ Taylor-Jones, Kate (2013). Rising Sun, Divided Land: Japanese and South Korean Filmmakers. Columbia University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0231165853.

- ^ a b Paquet, Darcy. "1970s". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Min, p.51-52.

- ^ Hartzell, Adam (March 2005). "A Review of Im Kwon-Taek: The Making of a Korean National Cinema". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ a b Chua, Beng Huat; Iwabuchi, Koichi, eds. (2008). East Asian Pop Culture: Analysing the Korean Wave. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 16–22. ISBN 978-9622098923.

- ^ Jameson, Sam (19 June 1989). "U.S. Films Troubled by New Sabotage in South Korea Theater". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "'Movie Industry Heading for Crisis'". www.koreatimes.co.kr.

- ^ Brown, James (9 February 2007). "Screen quotas raise tricky issues". Variety.

- ^ "Korean movie workers stage mass rally to protest quota cut". Korea Is One. Archived from the original on 26 May 2006. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ Artz, Lee; Kamalipour, Yahya R., eds. (2007). The Media Globe: Trends in International Mass Media. New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. p. 41. ISBN 978-0742540934.

- ^ Rosenberg, Scott (1 December 2004). "Thinking Outside the Box". Film Journal International. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ Lee, Hyo-won (18 November 2013). "Original 'Oldboy' Gets Remastered, Rescreened for 10th Anniversary in South Korea". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Box Office: All Time". Korean Film Council. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Pomerantz, Dorothy (8 September 2014). "What The Economics Of 'Snowpiercer' Say About The Future Of Film". Forbes. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Kang Kim, Hye Won (11 January 2018). "Could K-Film Ever Be As Popular As K-Pop In Asia?". Forbes. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "PARASITE Crowned Best Foreign Language Film at Golden Globes". Korean Film Biz Zone.

- ^ Khatchatourian, Klaritza Rico,Maane; Rico, Klaritza; Khatchatourian, Maane (10 February 2020). "'Parasite' Becomes First South Korean Movie to Win Best International Film Oscar".

- ^ Leanne Dawson (2015) Queer European Cinema: queering cinematic time and space, Studies in European Cinema, 12:3, 185-204, DOI: 10.1080/17411548.2015.1115696

- ^ a b c d Kim, Ungsan (2 January 2017). "Queer Korean cinema, national others, and making of queer space in Stateless Things (2011)". Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema. 9 (1): 61–79. doi:10.1080/17564905.2017.1296803. ISSN 1756-4905. S2CID 152116199.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i 김필호; C. COLIN SINGER (June 2011). "Three Periods of Korean Queer Cinema: Invisible, Camouflage, and Blockbuster". Acta Koreana. 14 (1): 117–136. doi:10.18399/acta.2011.14.1.005. ISSN 1520-7412.

- ^ a b c d Lee, Jooran (28 November 2000). "Remembered Branches: Towards a Future of Korean Homosexual Film". Journal of Homosexuality. 39 (3–4): 273–281. doi:10.1300/J082v39n03_12. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 11133136. S2CID 26513122.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shin, Jeeyoung (2013). "Male Homosexuality in The King and the Clown: Hybrid Construction and Contested Meanings". Journal of Korean Studies. 18 (1): 89–114. doi:10.1353/jks.2013.0006. ISSN 2158-1665. S2CID 143374035.

- ^ Giammarco, Tom. (2013). Queer Cinema. In C. Balmain (Ed.), Directory of World Cinema: South Korea (pp. 170-171) Chicago, IL: Intellect.

- ^ Balmain, Colette. (2013). Queer Cinema. In C. Balmain (Ed.), Directory of World Cinema: South Korea (pp. 175-176) Chicago, IL: Intellect.

- ^ Kim, Ungsan (2 January 2017). "Queer Korean cinema, national others, and making of queer space in Stateless Things (2011)". Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema. 9 (1): 61–79. doi:10.1080/17564905.2017.1296803. ISSN 1756-4905. S2CID 152116199.

- ^ a b Conran, Pierce. (2013). Queer Cinema. In C. Balmain (Ed.), Directory of World Cinema: South Korea (pp. 178-179) Chicago, IL: Intellect.

- ^ a b Giammarco, Tom. (2013). Queer Cinema. In C. Balmain (Ed.), Directory of World Cinema: South Korea (pp. 173-174) Chicago, IL: Intellect.

- ^ "영화 '아가씨' 원작… 800쪽이 금세 읽힌다". www.chosun.com (in Korean). Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Shin, Chi-Yun (2 January 2019). "In another time and place: The Handmaiden as an adaptation". Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema. 11 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/17564905.2018.1520781. ISSN 1756-4905.

- ^ Paquet, Darcy. "Film Awards Ceremonies in Korea". KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Steger, Isabella (10 October 2017). "South Korea's Busan film festival is emerging from under a dark political cloud". Quartz. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "IMDb OSCARS". IMDb. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ "Prizes & Honours". Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "Cannes Film Festival". IMDb. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "History of Biennale Cinema". La Biennale di Venezia. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "Announcing the TIFF '19 Award Winners". TIFF. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ "2013 Sundance Film Festival Announces Feature Film Awards". Sundance Institute. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ "Telluride Film Festival". IMDb. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ "Tokyo International Film Festival". IMDb. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "Locarno International Film Festival". IMDb. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Bowyer, Justin (2004). The Cinema of Japan and Korea. London: Wallflower Press. ISBN 1-904764-11-8.

- Min, Eungjun; Joo Jinsook; Kwak HanJu (2003). Korean Film : History, Resistance, and Democratic Imagination. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-95811-6.

- New Korean Cinema (2005), ed. by Chi-Yun Shin and Julian Stringer. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0814740309

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cinema of South Korea. |

대한민국의 영화

| 대한민국의 영화 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 스크린 수 | 2,424개 (2015년)[1] |

| 주요 배급사 | CJ엔터테인먼트 22% 쇼박스 17% 월트 디즈니 컴퍼니 코리아 11%[1] |

| 제작된 장편 영화 (2015년)[1] | |

| 총 편수 | 269 |

| 관객수 (2015년)[1] | |

| 총 관객수 | 2억 1729만 명 |

| 자국영화 관객수 | 1억 1293만 명 (52%) |

| 매출액 (2015년)[1] | |

| 총 매출 | 1조 7154억 원 |

| 자국영화 매출 | 8796억 원 |

대한민국의 영화(大韓民國- 映畵)는 대한민국 국적자 혹은 법인에 의해 제작된 영화로써, 주로 한국인 제작진과 배우로 구성된 영화를 지칭한다. 그리고 대한민국의 영화는 일제 강점기의 영화에 기원하며, 예술과 산업으로서 다양한 종류와 내용의 영화가 매년 제작되고 있다.

역사[편집]

광복 이후[편집]

일제강점기 후반부에는 검열과 동원으로 영화 제작이 어려웠다. 광복이 되자 영화인들은 거의 맨주먹으로 다시금 재기하기에 안간힘을 썼다. 이 당시의 영화는 광복의 감격을 표현한 작품이 대부분이었다. 최인규 감독이 전창근을 주연으로 해서 만든 《자유만세》, 윤봉춘 감독의 《안중근 사기(安重根史記)》, 이규환 감독의 《똘똘이의 모험》을 비롯하여 《3·1혁명기》·《해방된 내 고향》 등이 1946년에 제작되었으며, 다음해에도 민족의 고난과 독립투쟁을 말하는 《윤봉길 의사》·《불멸의 밀사》·《민족의 절규》 등 많은 작품을 내놓았다.그러나 한국의 영화가 그 예술적인 면에서 크게 진전을 본 것은 1960년 이후의 일이었다. 초창기로부터 해방 당시까지 그 의욕은 왕성했지만 예술적인 차원에서는 아직도 미숙했었다. 다른 예술과 마찬가지로 영화인들은 민족의 고뇌와 분노를 간접적으로 표현하는 데 영화를 하나의 수단으로 사용한 예가 오히려 많았다고 주장되기도 한다.[2]

텔레비전 보급 이후[편집]

영화를 제작하는 기업은 영세하고 시장은 협소하여 외화와 같이 영화제작에 충분한 시간과 경비를 투입할 수 없었고, 또한 자본주인 흥행사의 간섭 등으로 의욕있는 작품을 제작되기에는 어려운 여건에 놓여 있었다. 이와 같이 침체된 상황을 타개하기 위해 정부에서도 영화산업의 보호 육성책으로 1971년 2월에 영화진흥조합을 발족시켜 방화제작비 융자, 시나리오 창작금 지원, 영화인 복지사업 등을 추진하게 되었다.

1980년대 초에는 텔레비전 보급과 레저 산업의 성장에 의해 영화가 지녔던 대중 오락적 기능은 상대적으로 감소되어 영화산업이 사양화하고 있었지만 1986년 영화법 개정 이후 영화제작자유화로 활기를 띠기 시작했다. 1989년 제작된 방화는 1980년대 들어 가장 많은 106편에 달했다. 실제로 1989년은 방화가 물량면에서는 1980년대 들어 최다제작이 이루어졌으나 외화직배문제로 외화수입물량이 폭증하여 방화가 흥행에 성공하지 못했고, 관객의 방화외면, 외화의 선호현상이 더욱 심화된 것으로 나타났다. 또한, 외화는 방화보다도 많은 관객을 확보하고 있었다. 1980년대의 한국 영화계의 불황은 텔레비전 보급과 레저산업의 성장이라는 외적인 면보다는 내적인 면에 더 큰 원인이 있었고, 사회적·경제적·기술적인 제반 여건이 충족되지 않은 비정상적인 출발이 한국 영화를 산업으로 성장시키지 못하고 소규모의 기업에 머물게 하였다.[3]

같이 보기[편집]

각주[편집]

참고 자료[편집]

외부 링크[편집]

한국영화 (칸코쿠에이가)는 한국 국적을 가진 사람 또는 한국 법인에 의해 제작된 영화로 대부분의 경우 한국인 영화 스태프와 배우로 구성되며 주로 한국 국내 영화관 등에서 공개 되는 영화를 가리킨다.

역사 [ 편집 ]

일본 통치 시대 의 영화에 대해서는 일본 영화 #조선 을 참조.

1970년대 후반 한국은 텔레비전은 아직 흑백 모노럴 방송 으로 [1] , 다른 대중 오락이 따뜻해짐에 따라, 일본과 마찬가지로 영화의 제작 갯수는 줄어들고 있었지만, 아직 영화는 대중 오락의 수컷으로 이었다 [1] . 1977년까지는 14개의 영화제작사가 있었고, 1978년에는 6개의 회사가 있었고, 총 20개의 회사가 있었다 . [1] 독립 프로는 없었다 [1] . 상영 상황에 맞추어 정부 측으로부터 제작 개수의 조정 요청이 있어, 예년 1사가 연 6개 정도의 제작이지만, 1979년은 1사 5개라고 하는 요청이 있어, 연간 총 100개의 제작을 예정 되었다 [1] . 극장은 1979년에 한국 전역에서 약 500관 [1] . 수출은 홍콩, 대만, 미국의 일부로 일본에는 전혀 수출되지 않았다 [1] . 마켓이 아직 작아, 작품이 완성되어도 바로 개봉되지 않고, 미개봉 작품도 많았다. 당시 일본의 대형 영화사는 흥행 부진이 이어져, 자사 제작을 줄이고 있었기 때문에, 영화의 스탭이 촬영소에서 TV 영화 를 찍는 경우가 많았지만, 당시의 한국은 TV 영화는 전혀 없고, TV 드라마 는 모두 텔레비전 방송국 직원이 방송국 스튜디오 등에서 촬영했습니다 [1] . 요즘, 한국에서 인기가 있었던 영화는 아이돌 가수·혜니 주연의 「나만을 사랑해」와 같은 청춘 것, 「내가 멋진 여자」, 「O양의 아파트」등의 여성 영화, 문예물 등이 많이 제작되어 히트하고 있었다[1] . 일본 영화는 1개도 수입되지 않고, 1978년 12월에 오카다 시게루 일본 영화 제작자 연맹 회장들이 내한해, 한국의 영화 관계자를 모아 일본 영화 감상회를 열어, 「 행복의 노란 손수건」 와 『 야나기 일족의 음모』를 시사해, 정부의 요인도 만나, 양국의 영화 교류를 활성화하고 싶다고 일본 영화의 박람회를 여는 제안등을 했다 [1] .

뉴웨이브 [ 편집 ]

한국 영화사에서 중요한 사건이 3개 있었다. 1992년 삼성이 출자한 ' 결혼 이야기 ( Marriage Story ) '가 첫 정부 출자가 아닌 영화로 제작됐다. 1999년 ' 슈리 '가 공개돼 한국에서의 흥업수익의 50% 이상을 획득해 대성공을 거뒀다. 세 번째 사건으로 2001년 ' 엽기적인 그녀 '가 한국 영화사에서 가장 인기를 얻고 해외에서도 성공을 거뒀다.

영화제 [ 편집 ]

아시아 에서도 유수한 규모인 부산국제영화제 는 국내 영화진흥에도 큰 영향을 미치고 있다. 그 밖에 전주국제영화제, 부천국제판타스틱영화제 등 국내 각지에서 중소규모 영화제가 열리고 있다.

세계 3대 영화제 에서의 주요 수상 경력은 이하.

- 1987년 제44회 베니스국제영화제 여우주연상을 수상한 ' 대리인 '의 강수연

- 제55회 칸 국제영화제 (2002년)에서 임권택 감독 ' 취화선 ' 감독상

- 제59회 베니스국제영화제 (2002) 이창동 감독 의 ' 오아시스 '는 은사자상(감독상)

- 제61회 베네치아 국제영화제 (2004년)에서 김기덕 감독 ' 우츠세미 '가 은사자상(감독상), 제54회 베를린 국제영화제 (2004년)에서 이 감독의 ' 사마리아 '가 은곰상 (감독상)

- 제57회 칸 국제영화제 (2004년)에서 박찬욱 감독 ' 올드 보이 '가 심사위원 특별 그랑프리

- 제57회 베를린 국제영화제 (2007년)에서 박찬욱 감독 ' 사이보그에서도 괜찮다 '가 알프레드 바우어상

- 제60회 칸 국제영화제 (2007년)에서 ' 시크릿 선샤인 '의 전도영 이 여배우상

- 제62회 칸 국제영화제 (2009년)에서 박찬욱 감독 ' 갈증 '이 심사위원상

- 제63회 칸 국제영화제 (2010년)에서 『포에 토리 아그네스의 시』의 각본 이창동 (겸 감독)이 각본상

- 제61회 베를린 국제영화제 (2011년)에서 박찬욱 및 박창경 감독의 ' 나이트 피싱 '이 단편 부문 김곰상(작품상)

- 제69회 베니스국제영화제 (2012) 김기덕 감독 의 ' 피에타의 슬픔 '은 황금사자상(최고상 )

- 제69회 칸 국제영화제 (2016년)에서 『아가씨』의 프로덕션 디자이너 (미술감독) 류성희 가 발칸상 (예술공헌상)

- 제67회 베를린 국제영화제 (2017년)에서 ' 밤의 해변에서 혼자 '의 김미니 가 은곰상 (여배우상)

- 제71회 칸 국제영화제 (2018년)에서 ' 버닝 극장판 '의 미술감독 신정희 가 발칸상

- 김보라 감독의 ' 벌새 '가 2019년 제69회 베를린국제영화제 (2019) 베를린국제영화제 에서 14세 이상 부문 국제 심사위원 대상 그랑프리를 수상 한다.

- 제72회 칸 국제영화제 (2019년)에서 봉준호 감독 ' 파라사이트 반지하의 가족 '이 팔름돌 (최고상), 미술감독 이하준 이 발칸상

영화상 [ 편집 ]

이하 4상이 대표적인 영화상 이라고 하며, 시상식은 주최 또는 후원하는 텔레비전국에서 생중계된다. (괄호 안은 시상식의 개최월)

- 백상예술대상 [2] (4월) - 주최: 일간스포츠 , 중앙엔터테인먼트&스포츠 후원: 문화관광부 , 중앙일보사 , 중앙SUNDAY, 백상재단

- 대종상 [3] (7월) - 주최: 한국영화인협회, SBS , 중앙일보사 주관: SBS 프로덕션 후원: 문화관광부, 한국영화진흥위원회 , 한국예술단체총연합회, 한국영상자료원, 한국영화제작가협회, 전국극장연합회, 롯데시네마, 일간스포츠

- 대한민국 영화 대상 [4] (11월) - 주최: 문화방송 후원: 문화관광부, 한국영화진흥위원회

- 청룡영화상 (12월) - 주최: 스포츠조선 후원: 조선일보사 , 한국방송공사

정부와 영화의 관계 [ 편집 ]

영화 제작에 대한 공적 자금 원조도 진행되고 있다. 국립 예술가 양성시설인 한국예술종합학교 의 영상원이나 공적기관인 한국영화진흥위원회 부속의 영화학교인 한국영화아카데미 등을 거쳐 데뷔하는 영화인도 영화계를 지지하고 있다 . 국내 영화관에 연간 일정 일수 이상의 한국 영화 상영을 의무화하는 스크린 쿼터 제도 가 실시되고 있다. 검열 은 폐지되었지만 영상물등급위원회에 의해 행해지는 레이팅 은 일본보다 엄격하고 초등학생도 감상할 수 있다고 판정되는 영화는 패밀리 영화 등 일부 작품에 한정된다.

스크린 쿼터 제도 부디 이론 [ 편집 ]

한국 영화사는 중소규모가 많아 경제적 기반이 취약하다. 할리우드 영화 등 대자본 영화 작품이 한국 국내로 유입되면 한국 영화가 폐해진다는 위기감을 영화 관계자나 배우 등은 가지고 있다. '영화는 문화'의 대의하에 스크린 쿼터제가 도입되어 유지되고 있다.

미국에서 자주 폐지, 자유화를 요구받고 있었던 것, 한국 정부에 의한 한미 FTA 체결 추진 목적으로, 한국 정부는 2006년, 연간 상영 일수의 40%를 한국 영화로 하는 보호를 풀어, 반으로 줄이기로 결정. 이 결정을 받아 이병헌 , 장동건 을 비롯한 한국 배우진은 한국영화의 보호를 요구해 '영화인 릴레이 1인 시위 '를 하거나, 농성을 하는 등을 하고 반대 운동을 한다.た[5] [6]。

한국영화 흥행 성적 랭킹 [ 편집 ]

한국 [ 편집 ]

(배급 회사, 공개 연도 모두 한국 공개시의 것. 작품명은 방제.) 이하를 참고로 편집

- 2001년까지 공개의 작품의 관객수: 스포츠 KHAN (스포츠 쿄고) 2009-01-09 22:11:29

( http://sports.khan.co.kr/news/sk_index.html?cat=view&art_id=200901092211293&sec_id=540401&pt=nv )

※2001년까지 공개된 작품은 전국동원수 통계가 없기 때문에 추측치나 개산이 된다

- 2002년 이후 공개된 작품의 관객수: 한국영화진흥위원회 역대박스오피스(공식통계기준)( http://www.kobis.or.kr/kobis/business/stat/offc/findFormerBoxOfficeList.do?loadEnd= 0&searchType=search&sMultiMovieYn=&sRepNationCd= )

- 2019年公開の作品の観客数:韓国映画振興委員会 2019年1月 韓国映画産業 決算報告書(http://www.kofic.or.kr/kofic/business/board/selectBoardList.do?boardNumber=2 )

| 순위 | 작품 | 배급사 | 공개 연도 | 관객동원수 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 배틀 오션 해상 결전 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2014년 | 17,613,682명 |

| 2 | 익스트림 작업 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2019년 | 16,264,944명 |

| 3 | 하나님과 함께 제 1 장 : 죄와 처벌 | 롯데엔터테인먼트 | 2017년 | 14,410,754명 |

| 4 | 국제 시장에서 만나자. | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2014년 | 14,257,115명 |

| 5 | 베테랑 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2015년 | 13,414,009명 |

| 6 | 괴물-한강의 괴물- | 쇼박스 | 2006년 | 13,019,740명 |

| 7 | 10명의 도둑들 | 쇼박스 | 2012년 | 12,983,330명 |

| 8 | 7번방의 기적 | 다음 엔터테인먼트 월드 | 2013년 | 12,811,206명 |

| 9 | 암살 | 쇼박스 | 2015년 | 12,705,770명 |

| 10 | 왕이 된 남자 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2012년 | 12,319,542명 |

| 11 | 왕의 남자 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2006년 | 12,302,831명 |

| 12 | 하나님과 함께 제 2 장 : 요인과 인연 | 롯데엔터테인먼트 | 2018년 | 12,274,996명 |

| 13 | 택시 운전사 약속은 바다를 넘어 | 쇼박스 | 2017년 | 12,186,684명 |

| 14 | 형제 후드 | 쇼박스 | 2004년 | 11,746,135명 |

| 15 | 새로운 감염 파이널 익스프레스 | 다음 엔터테인먼트 월드 | 2016년 | 11,565,479명 |

| 16 | TSUNAMI -쓰나미- | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2009년 | 11,453,338명 |

| 17 | 변호인 | 다음 엔터테인먼트 월드 | 2013년 | 11,375,944명 |

| 18 | 실미드 | 시네마 서비스 | 2003년 | 11,081,000명 |

| 19 | 파라 사이트 반 지하 가족 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2019년 | 10,313,086명 |

| 20 | 화려한 리벤지 | 쇼박스 | 2016년 | 9,707,581명 |

| 21 | EXIT 이그짓 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2019년 | 9,426,051명 |

| 22 | 스노우 피어서 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2013년 | 9,349,991명 |

| 23 | 관상사 -칸소시- | 쇼박스 | 2013년 | 9,134,586명 |

| 24 | 해적 | 롯데엔터테인먼트 | 2014년 | 8,666,046명 |

| 25 | 수상한 그녀 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2014년 | 8,656,397명 |

| 26 | 국가대표!? | 쇼박스 | 2009년 | 8,487,894명 |

| 27 | D-WARS 디 워즈 | 쇼박스 | 2007년 | 8,426,973명 |

| 28 | 백두산 대분화 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2019년 | 8,252,669명 |

| 29 | 과속 스캔들 | 롯데엔터테인먼트 | 2008년 | 8,245,523명 |

| 30 | 친구에게 칭 | 코리아픽처스 | 2001년 | 8,181,377명 |

| 31 | 톤 맥콜에 오신 것을 환영합니다 | 쇼박스 | 2005년 | 8,008,622명 |

| 32 | 컨피덴셜/공조 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2016년 | 7,817,459명 |

| 33 | 히말라야~지상 8,000미터의 인연~ | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2015년 | 7,759,431명 |

| 34 | 밀정 | 워너 브라더스 코리아 | 2016년 | 7,500,420명 |

| 35 | 카미미-KAMIYUMI- | 롯데엔터테인먼트 | 2011년 | 7,470,633명 |

| 36 | 써니 영원한 친구 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2011년 | 7,362,467명 |

| 37 | 광주 5·18 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2007년 | 7,307,993명 |

| 38 | 1987, 한 싸움의 진실 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2017년 | 7,231,638명 |

| 39 | 베를린 파일 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2013년 | 7,166,199명 |

| 40 | MASTER/마스터 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2016년 | 7,147,879명 |

| 41 | 터널 어둠에 갇힌 남자 | 쇼박스 | 2016년 | 7,120,508명 |

| 42 | 내부자 / 내부자 | 쇼박스 | 2016년 | 7,072,015명 |

| 43 | 오퍼레이션 크로마이트 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2016년 | 7,049,643명 |

| 44 | LUCK-KEY/럭키 | 쇼박스 | 2016년 | 6,975,290명 |

| 45 | 시크릿 미션 | 쇼박스 | 2013년 | 6,959,083명 |

| 46 | 함성/콕슨 | 20세기 폭스 코리아 | 2016년 | 6,879,908명 |

| 47 | 범죄 도시 | KIWI 엔터테인먼트 그룹 | 2017년 | 6,879,841명 |

| 48 | 타차 이카사마사 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2006년 | 6,847,777명 |

| 49 | 좋은 배드 위어드 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2008년 | 6,686,912명 |

| 50 | 내 늑대 소년 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2012년 | 6,654,837명 |

| 51 | 칸나 씨 큰 성공입니다! | 쇼박스 | 2006년 | 6,619,498명 |

| 52 | 군함도 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2017년 | 6,592,151명 |

| 53 | 아조시 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2010년 | 6,282,774명 |

| 54 | 왕의 운명 - 역사를 바꾼 8일간 - | 쇼박스 | 2015년 | 6,246,849명 |

| 55 | 슈리 | 삼성 픽처스 (제공) | 1999년 | 6,209,893명 |

| 56 | 정우치 시공도사 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2009년 | 6,136,928명 |

| 57 | 내 보스 내 영웅 2 리턴스 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2006년 | 6,105,431명 |

| 58 | 노던 리미트 라인 남북해전 | 다음 엔터테인먼트 월드 | 2015년 | 6,043,784명 |

| 59 | JSA | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2000년 | 5,830,228명 |

| 60 | 미드나이트 러너 | 롯데엔터테인먼트 | 2017년 | 5,653,270명 |

| 61 | 가문 위기 | 쇼박스 | 2005년 | 5,635,266명 |

| 62 | 카렌보 | 다음 엔터테인먼트 월드 | 2013년 | 5,604,104명 |

| 63 | 라스트 프린세스 대한제국 마지막 황녀 | 롯데엔터테인먼트 | 2016년 | 5,599,229명 |

| 64 | 테러, 라이브 | 롯데엔터테인먼트 | 2013년 | 5,583,596명 |

| 65 | 감시자들 | 다음 엔터테인먼트 월드 | 2013년 | 5,508,017명 |

| 66 | 의형제 SECRET REUNION | 쇼박스 | 2010년 | 5,507,106명 |

| 67 | 프리스트 악마를 묻는 자 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2015년 | 5,442,553명 |

| 68 | 안시 성 그레이트 배틀 | 다음 엔터테인먼트 월드 | 2018년 | 5,440,186명 |

| 69 | 더 킹 | 다음 엔터테인먼트 월드 | 2016년 | 5,316,015명 |

| 70 | 왕두기 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2011년 | 5,310,510명 |

| 71 | 완벽한 타인 | 롯데엔터테인먼트 | 2018년 | 5,293,435명 |

| 72 | 신부는 갱스터 | 코리아픽처스 | 2001년 | 5,260,451명 |

| 73 | 살인의 추억 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2003년 | 5,255,376명 |

| 74 | 타워 초고층 빌딩 대화재 | CJ E&M 영화 부문 | 2012년 | 5,181,014명 |

| 75 | 마라톤 | 쇼박스 | 2005년 | 5,148,022명 |

| 76 | 힘든 결혼 | 시네마 서비스 | 2002년 | 5,089,966명 |

| 77 | 체이서 | 쇼박스 | 2008년 | 5,071,619명 |

| 78 | 독전 BELIEVER | 다음 엔터테인먼트 월드 | 2018년 | 5,063,620명 |

| 79 | 공작 흑금성이라는 남자 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2018년 | 4,974,512명 |

| 80 | 같은 해의 가정 교사 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2003년 | 4,937,573명 |

| 81 | 바람과 함께 떠나지 않는다!? | 다음 엔터테인먼트 월드 | 2012년 | 4,909,937명 |

| 82 | 엽기적인 그녀 | 시네마 서비스 | 2001년 | 4,882,495명 |

| 83 | 너, 그 강을 건너지 마라. | CGV 아트하우스,대명문화공장 | 2014년 | 4,801,527명 |

| 84 | 봉황동 전투 | 쇼박스 | 2019년 | 4,787,538명 |

| 85 | 조선명탐정 트리카부트의 비밀 | 쇼박스 | 2011년 | 4,786,259명 |

| 86 | 군도 | 쇼박스 | 2014년 | 4,774,895명 |

| 87 | KCIA 남산의 부장들 | 쇼박스 | 2020년 | 4,750,104명 |

| 88 | 나쁜 녀석 | 쇼박스 | 2012년 | 4,719,872명 |

| 89 | 새로운 세계 | 다음 엔터테인먼트 월드 | 2013년 | 4,682,492명 |

| 90 | 토가니 어린 눈동자의 고발 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2011년 | 4,662,822명 |

| 91 | 내 아내의 모든 | 다음 엔터테인먼트 월드 | 2012년 | 4,598,583명 |

| 92 | 판도라 | 다음 엔터테인먼트 월드 | 2016년 | 4,583,648명 |

| 93 | 더 배드 가이즈 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2019년 | 4,573,902명 |

| 94 | 용가시 변종 증식 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2012년 | 4,515,833명 |

| 95 | 풍림고 | 시네마 서비스 | 2001년 | |

| 96 | 강철 비 | 다음 엔터테인먼트 월드 | 2017년 | 4,452,740명 |

| 97 | 그냥 악에서 구할 때까지 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2020년 | 4,357,803명 |

| 98 | 강철준 공공의 적 1-1 | 시네마 서비스 | 2008년 | 4,300,670명 |

| 99 | 아가씨 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2016년 | 4,299,951명 |

| 100 | 할머니의 집 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2002년 | 4,193,826명 |

| 101 | 서스펙트 슬픔 용의자 | 쇼박스 | 2013년 | 4,131,248명 |

| 102 | 건축학 개론 | 롯데엔터테인먼트 | 2012년 | 4,110,645명 |

| 103 | 타이푼/TYPHOON | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2005년 | 4,094,395명 |

| 104 | 7급 공무원 | 롯데엔터테인먼트 | 2009년 | 4,088,799명 |

| 105 | 섹스 이즈 제로 | 쇼박스 | 2002년 | 4,082,797명 |

| 106 | 댄싱 퀸 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2012년 | 4,057,546명 |

| 107 | 우리의 평생 최고의 순간 | 사이다스 FNH | 2008년 | 4,044,582명 |

| 108 | 스윈더러스 | 쇼박스 | 2017년 | 4,018,341명 |

| 109 | 타차 하나님의 손 | CJ엔터테인먼트 | 2014년 | 4,015,361명 |

일본 [ 편집 ]

| 작품 | 배급사 | 공개 연도 | 흥행 소득 | 관객동원수 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 파라 사이트 반 지하 가족 | 비터스 엔드 | 2020년 | 47.4억엔 | |

| 내 머리에 지우개 | GAGA USEN | 2005년 | 30억엔 | |

| 4월의 눈 | UIP | 2005년 | 27.5억엔 | 270만명 |

| 나의 그녀를 소개합니다 | 워너 | 2004년 | 20억엔 | 137만명 |

| 슈리 | 어뮤즈 | 2000년 | 18억엔 | 130만명 |

| 형제 후드 | UIP | 2004년 | 15억엔 | |

| JSA | 어뮤즈 | 2001년 | 11.6억엔 | |

| 음성 | 월트 디즈니 스튜디오 | 2003년 | 10억엔 | |

| 누구에게나 비밀이 | 도시바 엔터테인먼트 | 2004년 | 9억엔 | |

| 스캔들 | 씨네 Quanon , 쇼치쿠 | 2004년 | 9억엔 | |

| 달콤한 삶 | 카도카와 영화 | 2005년 | 6.5억엔 | |

| 실미드 | 토에이 | 2004년 | 6억엔 | 50만명 |

・

각주 [ 편집 ]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j “시나리오 작가 대담 이시모리 시로 vs 김지채 -한일 라이터 얼굴 맞추기- 쓰는 것·살아가는·상상' '월간 시나리오' 일본 시나리오 작가 협회 , 1979년 8월, 87- 91페이지.

- ^ (조선어) 공식 사이트 . 영화, 텔레비전의 2 종류가 있다. TV는 드라마, 교양 프로그램, 연예 프로그램(오락 프로그램)이 대상. 시상식은 SBS 계열로 중계 방송된다. 제37회(2001년)까지는 연극 부문도 있었다. 제1회는 1965년. 제39회(2003년)까지는 한국일보사 가 주최하고 있었다. (조선어) 제39회 공식 사이트 참조.

- ^ (조선어) 공식 사이트 . 제1회는 1962년.

- ^ (조선어) 공식 사이트 . 제1회(2002년)는 MBC 영화상으로서 개최.

- ↑ 2006년 7월 2일 Innolife.net 이병헌, “스크린 쿼터 문제는 영화계만의 문제가 아닙니다.”

- ↑ 2006년 2월 9일 JANJAN 영화배우 장동건이 국회에서 1인 시위

관련 항목 [ 편집 ]

외부 링크 [ 편집 ]

韓国映画

韓国映画(かんこくえいが)は、韓国国籍を持つ者または韓国の法人によって製作された映画で、ほとんどの場合、韓国人の映画スタッフと俳優で構成され、主に韓国国内の映画館などで公開される映画を指す。

歴史[編集]

1970年代後半の韓国はテレビはまだ白黒モノラル放送で[1]、他の大衆娯楽がゆたかになるにつれ、日本と同様、映画の製作本数は減ってはいたが、まだ映画は大衆娯楽の雄であった[1]。1977年まで映画の制作会社は14社あり、1978年に6社増え計20社となった[1]。独立プロはなかった[1]。上映状況に合わせて政府側から製作本数の調整要請があり、例年1社が年6本程度の製作であるが、1979年は1社5本という要請があり、年間計100本の製作を予定された[1]。劇場は1979年に韓国全土で約500館[1]。輸出は香港、台湾、アメリカの一部で、日本へは全く輸出されていなかった[1]。マーケットがまだ小さく、作品が完成してもすぐ封切りにならず、未封切作品も多かった。当時日本の大手映画会社は興行不振が続き、自社製作を減らしていたため、映画のスタッフが撮影所でテレビ映画を撮ることが多かったが、当時の韓国はテレビ映画は全くなく、テレビドラマは全てテレビ局のスタッフが局のスタジオ等で撮影していた[1]。この頃、韓国で人気があった映画はアイドル歌手・へウニ主演の『私だけを愛して』のような青春もの、『私がすてた女』、『O嬢のアパート』等の女性映画、文芸ものなどが多く製作されヒットしていた[1]。日本映画は1本も輸入されず、1978年12月に岡田茂日本映画製作者連盟会長らが来韓し、韓国の映画関係者を集めて日本映画鑑賞会を開き、『幸福の黄色いハンカチ』と『柳生一族の陰謀』を試写し、政府の要人にも会い、両国の映画交流を活性化したいと日本映画の見本市を開く提案等をした[1]。

ニューウェーブ[編集]

韓国の映画史において重要な出来事が3つあった。1992年、サムソンが出資した 『결혼 이야기(Marriage Story)』が初の政府出資でない映画として制作された。1999年、『シュリ』が公開され、韓国における興業収益の50%以上を獲得して大成功を収めた。3つ目の出来事として2001年の『猟奇的な彼女』が韓国映画史においてもっとも人気を収め、海外でも成功をおさめた。

映画祭[編集]

アジアでも有数の規模である釜山国際映画祭は、国内の映画振興にも大きな影響を及ぼしている。そのほか、全州国際映画祭、富川国際ファンタスティック映画祭など韓国国内各地で中小規模の映画祭が開かれている。

世界三大映画祭での主な受賞歴は以下。

- 第44回ヴェネツィア国際映画祭(1987年)で『シバジ』のカン・スヨンが女優賞

- 第55回カンヌ国際映画祭(2002年)でイム・グォンテク監督『酔画仙』が監督賞

- 第59回ヴェネツィア国際映画祭(2002年)でイ・チャンドン監督『オアシス』 が銀獅子賞(監督賞)

- 第61回ヴェネツィア国際映画祭(2004年)でキム・ギドク監督『うつせみ』 が銀獅子賞(監督賞)、第54回ベルリン国際映画祭(2004年)で同監督の『サマリア』が銀熊賞(監督賞)

- 第57回カンヌ国際映画祭(2004年)でパク・チャヌク監督『オールド・ボーイ』が審査員特別グランプリ

- 第57回ベルリン国際映画祭(2007年)でパク・チャヌク監督『サイボーグでも大丈夫』がアルフレッド・バウアー賞

- 第60回カンヌ国際映画祭(2007年)で『シークレット・サンシャイン』のチョン・ドヨンが女優賞

- 第62回カンヌ国際映画祭(2009年)でパク・チャヌク監督『渇き』が審査員賞

- 第63回カンヌ国際映画祭(2010年)で『ポエトリー アグネスの詩』の脚本イ・チャンドン(兼 監督)が脚本賞

- 第61回ベルリン国際映画祭(2011年)でパク・チャヌクならびにパク・チャンギョン監督の『ナイト・フィッシング』が短編部門金熊賞(作品賞)

- 第69回ヴェネツィア国際映画祭(2012年)でキム・ギドク監督『嘆きのピエタ』 が金獅子賞(最高賞)

- 第69回カンヌ国際映画祭(2016年)で『お嬢さん』のプロダクションデザイナー(美術監督)リュ・ソンヒがバルカン賞(芸術貢献賞)

- 第67回ベルリン国際映画祭(2017年)で『夜の浜辺でひとり』のキム・ミニが銀熊賞(女優賞)

- 第71回カンヌ国際映画祭(2018年)で『バーニング 劇場版』の美術監督シン・ジョンヒがバルカン賞

- 第69回ベルリン国際映画祭(2019年)でキム・ボラ監督『はちどり』がジェネレーション14プラス部門インターナショナル審査員賞グランプリ

- 第72回カンヌ国際映画祭(2019年)でポン・ジュノ監督『パラサイト 半地下の家族』がパルム・ドール(最高賞)、美術監督のイ・ハジュンがバルカン賞

映画賞[編集]

以下4賞が代表的な映画賞といわれ、授賞式は主催または後援するテレビ局で生中継される。(カッコ内は授賞式の開催月)

- 百想芸術大賞[2](4月) - 主催:日刊スポーツ、中央エンタテインメント&スポーツ 後援:文化観光部、中央日報社、中央SUNDAY、百想財団

- 大鐘賞[3](7月) - 主催:韓国映画人協会、SBS、中央日報社 主管:SBSプロダクション 後援:文化観光部、韓国映画振興委員会、韓国芸術団体総連合会、韓国映像資料院、韓国映画製作家協会、全国劇場連合会、ロッテシネマ、日刊スポーツ

- 大韓民国映画大賞[4](11月)- 主催:文化放送 後援:文化観光部、韓国映画振興委員会

- 青龍映画賞(12月) - 主催:スポーツ朝鮮 後援:朝鮮日報社、韓国放送公社

政府と映画の関係[編集]

映画製作への公的資金援助も行われている。国立の芸術家養成施設である韓国芸術総合学校の映像院や、公的機関である韓国映画振興委員会付属の映画学校である韓国映画アカデミーなどを経てデビューする映画人も映画界を支えている。国内の映画館に、年間一定日数以上の韓国映画上映を義務づけるスクリーンクォータ制度が実施されている。検閲は廃止されたが、映像物等級委員会により行われるレイティングは日本より厳しく、小学生も鑑賞できると判定される映画はファミリー映画など一部の作品に限られる。

スクリーンクォータ制度是非論[編集]

韓国の映画会社は中小規模のものが多く、経済的基盤が脆弱である。ハリウッド映画などの大資本の映画作品が韓国国内に流入すると、韓国映画が廃れるという危機感を映画関係者や俳優などは持っている。「映画は文化」の大義のもとスクリーンクォータ制が導入され維持されている。

アメリカ合衆国からかたたびたび廃止、自由化を求められていたこと、韓国政府による韓米FTA締結推進目的から、韓国政府は2006年、年間上映日数の40%を韓国映画とする保護を緩めて、半数に減らすことに決定。この決定を受けてイ・ビョンホン、チャン・ドンゴンをはじめとした韓国の俳優陣は韓国映画の保護を求めて「映画人リレー一人デモ」をしたり、座り込みをするなどをして反対運動をおこなった[5][6]。

韓国映画興行成績ランキング[編集]

韓国[編集]

(配給会社、公開年度共に韓国公開時のもの。作品名は邦題。) 以下を参考に編集

- 2001年まで公開の作品の観客数:スポーツKHAN(スポーツ京郷) 2009-01-09 22:11:29

(http://sports.khan.co.kr/news/sk_index.html?cat=view&art_id=200901092211293&sec_id=540401&pt=nv )

※2001年まで公開の作品は全国動員数の統計がないため推測値や概算となる

- 2002年以降公開の作品の観客数:韓国映画振興委員会 歴代ボックスオフィス(公式統計基準)(http://www.kobis.or.kr/kobis/business/stat/offc/findFormerBoxOfficeList.do?loadEnd=0&searchType=search&sMultiMovieYn=&sRepNationCd= )

- 2019年公開の作品の観客数:韓国映画振興委員会 2019年1月 韓国映画産業 決算報告書(http://www.kofic.or.kr/kofic/business/board/selectBoardList.do?boardNumber=2 )

| 順位 | 作品 | 配給会社 | 公開年度 | 観客動員数 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | バトル・オーシャン 海上決戦 | CJエンタテインメント | 2014年 | 17,613,682人 |

| 2 | エクストリーム・ジョブ | CJエンタテインメント | 2019年 | 16,264,944人 |

| 3 | 神と共に 第一章:罪と罰 | ロッテエンタテインメント | 2017年 | 14,410,754人 |

| 4 | 国際市場で逢いましょう | CJエンタテインメント | 2014年 | 14,257,115人 |

| 5 | ベテラン | CJエンタテインメント | 2015年 | 13,414,009人 |

| 6 | グエムル-漢江の怪物- | ショーボックス | 2006年 | 13,019,740人 |

| 7 | 10人の泥棒たち | ショーボックス | 2012年 | 12,983,330人 |

| 8 | 7番房の奇跡 | ネクスト・エンターテインメント・ワールド | 2013年 | 12,811,206人 |

| 9 | 暗殺 | ショーボックス | 2015年 | 12,705,770人 |

| 10 | 王になった男 | CJエンタテインメント | 2012年 | 12,319,542人 |

| 11 | 王の男 | CJエンタテインメント | 2006年 | 12,302,831人 |

| 12 | 神と共に 第二章:因と縁 | ロッテエンタテインメント | 2018年 | 12,274,996人 |

| 13 | タクシー運転手 約束は海を越えて | ショーボックス | 2017年 | 12,186,684人 |

| 14 | ブラザーフッド | ショーボックス | 2004年 | 11,746,135人 |

| 15 | 新感染 ファイナル・エクスプレス | ネクスト・エンターテインメント・ワールド | 2016年 | 11,565,479人 |

| 16 | TSUNAMI -ツナミ- | CJエンタテインメント | 2009年 | 11,453,338人 |

| 17 | 弁護人 | ネクスト・エンターテインメント・ワールド | 2013年 | 11,375,944人 |

| 18 | シルミド | シネマサービス | 2003年 | 11,081,000人 |

| 19 | パラサイト 半地下の家族 | CJエンタテインメント | 2019年 | 10,313,086人 |

| 20 | 華麗なるリベンジ | ショーボックス | 2016年 | 9,707,581人 |

| 21 | EXIT イグジット | CJエンタテインメント | 2019年 | 9,426,051人 |

| 22 | スノーピアサー | CJエンタテインメント | 2013年 | 9,349,991人 |

| 23 | 観相師 -かんそうし- | ショーボックス | 2013年 | 9,134,586人 |

| 24 | パイレーツ | ロッテエンタテインメント | 2014年 | 8,666,046人 |

| 25 | 怪しい彼女 | CJエンタテインメント | 2014年 | 8,656,397人 |

| 26 | 国家代表!? | ショーボックス | 2009年 | 8,487,894人 |

| 27 | D-WARS ディー・ウォーズ | ショーボックス | 2007年 | 8,426,973人 |

| 28 | 白頭山大噴火 | CJエンタテインメント | 2019年 | 8,252,669人 |

| 29 | 過速スキャンダル | ロッテエンタテインメント | 2008年 | 8,245,523人 |

| 30 | 友へ チング | コリアピクチャーズ | 2001年 | 8,181,377人 |

| 31 | トンマッコルへようこそ | ショーボックス | 2005年 | 8,008,622人 |

| 32 | コンフィデンシャル/共助 | CJエンタテインメント | 2016年 | 7,817,459人 |

| 33 | ヒマラヤ〜地上8,000メートルの絆〜 | CJエンタテインメント | 2015年 | 7,759,431人 |

| 34 | 密偵 | ワーナー・ブラザース・コリア | 2016年 | 7,500,420人 |

| 35 | 神弓-KAMIYUMI- | ロッテエンタテインメント | 2011年 | 7,470,633人 |

| 36 | サニー 永遠の仲間たち | CJエンタテインメント | 2011年 | 7,362,467人 |

| 37 | 光州5・18 | CJエンタテインメント | 2007年 | 7,307,993人 |

| 38 | 1987、ある闘いの真実 | CJエンタテインメント | 2017年 | 7,231,638人 |

| 39 | ベルリンファイル | CJエンタテインメント | 2013年 | 7,166,199人 |

| 40 | MASTER/マスター | CJエンタテインメント | 2016年 | 7,147,879人 |

| 41 | トンネル 闇に鎖された男 | ショーボックス | 2016年 | 7,120,508人 |

| 42 | インサイダーズ/内部者たち | ショーボックス | 2016年 | 7,072,015人 |

| 43 | オペレーション・クロマイト | CJエンタテインメント | 2016年 | 7,049,643人 |

| 44 | LUCK-KEY/ラッキー | ショーボックス | 2016年 | 6,975,290人 |

| 45 | シークレット・ミッション | ショーボックス | 2013年 | 6,959,083人 |

| 46 | 哭声/コクソン | 20世紀フォックス・コリア | 2016年 | 6,879,908人 |

| 47 | 犯罪都市 | KIWIエンタテインメントグループ | 2017年 | 6,879,841人 |

| 48 | タチャ イカサマ師 | CJエンタテインメント | 2006年 | 6,847,777人 |

| 49 | グッド・バッド・ウィアード | CJエンタテインメント | 2008年 | 6,686,912人 |

| 50 | 私のオオカミ少年 | CJエンタテインメント | 2012年 | 6,654,837人 |

| 51 | カンナさん大成功です! | ショーボックス | 2006年 | 6,619,498人 |

| 52 | 軍艦島 | CJエンタテインメント | 2017年 | 6,592,151人 |

| 53 | アジョシ | CJエンタテインメント | 2010年 | 6,282,774人 |

| 54 | 王の運命 -歴史を変えた八日間- | ショーボックス | 2015年 | 6,246,849人 |

| 55 | シュリ | サムスンピクチャーズ(提供) | 1999年 | 6,209,893人 |

| 56 | チョン・ウチ 時空道士 | CJエンタテインメント | 2009年 | 6,136,928人 |

| 57 | マイ・ボス マイ・ヒーロー2 リターンズ | CJエンタテインメント | 2006年 | 6,105,431人 |

| 58 | ノーザン・リミット・ライン 南北海戦 | ネクスト・エンターテインメント・ワールド | 2015年 | 6,043,784人 |

| 59 | JSA | CJエンタテインメント | 2000年 | 5,830,228人 |

| 60 | ミッドナイト・ランナー | ロッテエンタテインメント | 2017年 | 5,653,270人 |

| 61 | 家門の危機 | ショーボックス | 2005年 | 5,635,266人 |

| 62 | かくれんぼ | ネクスト・エンターテインメント・ワールド | 2013年 | 5,604,104人 |

| 63 | ラスト・プリンセス 大韓帝国最後の皇女 | ロッテエンタテインメント | 2016年 | 5,599,229人 |

| 64 | テロ、ライブ | ロッテエンタテインメント | 2013年 | 5,583,596人 |

| 65 | 監視者たち | ネクスト・エンターテインメント・ワールド | 2013年 | 5,508,017人 |

| 66 | 義兄弟 SECRET REUNION | ショーボックス | 2010年 | 5,507,106人 |

| 67 | プリースト 悪魔を葬る者 | CJエンタテインメント | 2015年 | 5,442,553人 |

| 68 | 安市城 グレート・バトル | ネクスト・エンターテインメント・ワールド | 2018年 | 5,440,186人 |

| 69 | ザ・キング | ネクスト・エンターテインメント・ワールド | 2016年 | 5,316,015人 |

| 70 | ワンドゥギ | CJエンタテインメント | 2011年 | 5,310,510人 |

| 71 | 完璧な他人 | ロッテエンタテインメント | 2018年 | 5,293,435人 |

| 72 | 花嫁はギャングスター | コリアピクチャーズ | 2001年 | 5,260,451人 |

| 73 | 殺人の追憶 | CJエンタテインメント | 2003年 | 5,255,376人 |

| 74 | ザ・タワー 超高層ビル大火災 | CJ E&M 映画部門 | 2012年 | 5,181,014人 |

| 75 | マラソン | ショーボックス | 2005年 | 5,148,022人 |

| 76 | 大変な結婚 | シネマサービス | 2002年 | 5,089,966人 |

| 77 | チェイサー | ショーボックス | 2008年 | 5,071,619人 |

| 78 | 毒戦 BELIEVER | ネクスト・エンターテインメント・ワールド | 2018年 | 5,063,620人 |

| 79 | 工作 黒金星と呼ばれた男 | CJエンタテインメント | 2018年 | 4,974,512人 |

| 80 | 同い年の家庭教師 | CJエンタテインメント | 2003年 | 4,937,573人 |

| 81 | 風と共に去りぬ!? | ネクスト・エンターテインメント・ワールド | 2012年 | 4,909,937人 |

| 82 | 猟奇的な彼女 | シネマサービス | 2001年 | 4,882,495人 |

| 83 | あなた、その川を渡らないで | CGVアートハウス,デミョン文化工場 | 2014年 | 4,801,527人 |

| 84 | 鳳梧洞戦闘 | ショーボックス | 2019年 | 4,787,538人 |

| 85 | 朝鮮名探偵 トリカブトの秘密 | ショーボックス | 2011年 | 4,786,259人 |

| 86 | 群盗 | ショーボックス | 2014年 | 4,774,895人 |

| 87 | KCIA 南山の部長たち | ショーボックス | 2020年 | 4,750,104人 |

| 88 | 悪いやつら | ショーボックス | 2012年 | 4,719,872人 |

| 89 | 新しき世界 | ネクスト・エンターテインメント・ワールド | 2013年 | 4,682,492人 |

| 90 | トガニ 幼き瞳の告発 | CJエンタテインメント | 2011年 | 4,662,822人 |

| 91 | 僕の妻のすべて | ネクスト・エンターテインメント・ワールド | 2012年 | 4,598,583人 |

| 92 | パンドラ | ネクスト・エンターテインメント・ワールド | 2016年 | 4,583,648人 |

| 93 | ザ・バッド・ガイズ | CJエンタテインメント | 2019年 | 4,573,902人 |

| 94 | ヨンガシ 変種増殖 | CJエンタテインメント | 2012年 | 4,515,833人 |

| 95 | 風林高 | シネマサービス | 2001年 | |

| 96 | 鋼鉄の雨 | ネクスト・エンターテインメント・ワールド | 2017年 | 4,452,740人 |

| 97 | ただ悪から救いたまえ | CJエンタテインメント | 2020年 | 4,357,803人 |

| 98 | カン・チョルジュン 公共の敵1-1 | シネマサービス | 2008年 | 4,300,670人 |

| 99 | お嬢さん | CJエンタテインメント | 2016年 | 4,299,951人 |

| 100 | おばあちゃんの家 | CJエンタテインメント | 2002年 | 4,193,826人 |

| 101 | サスペクト 哀しき容疑者 | ショーボックス | 2013年 | 4,131,248人 |

| 102 | 建築学概論 | ロッテエンタテインメント | 2012年 | 4,110,645人 |

| 103 | タイフーン/TYPHOON | CJエンタテインメント | 2005年 | 4,094,395人 |

| 104 | 7級公務員 | ロッテエンタテインメント | 2009年 | 4,088,799人 |

| 105 | セックス イズ ゼロ | ショーボックス | 2002年 | 4,082,797人 |

| 106 | ダンシング・クィーン | CJエンタテインメント | 2012年 | 4,057,546人 |

| 107 | 私たちの生涯最高の瞬間 | サイダスFNH | 2008年 | 4,044,582人 |

| 108 | スウィンダラーズ | ショーボックス | 2017年 | 4,018,341人 |

| 109 | タチャ 神の手 | CJエンタテインメント | 2014年 | 4,015,361人 |

日本[編集]

| 作品 | 配給会社 | 公開年度 | 興行収入 | 観客動員数 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| パラサイト 半地下の家族 | ビターズ・エンド | 2020年 | 47.4億円 | |

| 私の頭の中の消しゴム | GAGA USEN | 2005年 | 30億円 | |

| 四月の雪 | UIP | 2005年 | 27.5億円 | 270万人 |

| 僕の彼女を紹介します | ワーナー | 2004年 | 20億円 | 137万人 |

| シュリ | アミューズ | 2000年 | 18億円 | 130万人 |

| ブラザーフッド | UIP | 2004年 | 15億円 | |

| JSA | アミューズ | 2001年 | 11.6億円 | |

| ボイス | ウォルト・ディズニー・スタジオ | 2003年 | 10億円 | |

| 誰にでも秘密がある | 東芝エンタテインメント | 2004年 | 9億円 | |

| スキャンダル | シネカノン、松竹 | 2004年 | 9億円 | |

| 甘い人生 | 角川映画 | 2005年 | 6.5億円 | |

| シルミド | 東映 | 2004年 | 6億円 | 50万人 |

・

脚注[編集]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j 「シナリオ作家対談 石森史郎vs金志軒 -日韓ライター顔合わせ- 書くこと・生きること・想うこと」『月刊シナリオ』日本シナリオ作家協会、1979年8月、87-91頁。

- ^ (朝鮮語)公式サイト。映画、テレビの2部門がある。テレビはドラマ、教養番組、芸能番組(娯楽番組)が対象。授賞式はSBS系列で中継放送される。第37回(2001年)までは演劇部門もあった。第1回は1965年。第39回(2003年)までは韓国日報社が主催していた。(朝鮮語)第39回公式サイト参照。

- ^ (朝鮮語)公式サイト。第1回は1962年。

- ^ (朝鮮語)公式サイト。第1回(2002年)はMBC映画賞として開催。

- ^ 2006年7月2日 Innolife.netイ・ビョンホン、「スクリーンクォーター問題は、映画界だけの問題ではありません。」

- ^ 2006年2月9日JANJAN映画俳優チャン・ドンゴンが国会で1人デモ

No comments:

Post a Comment