Park Yuha

4년전에 이렇게 썼다. 지금도 마찬가지다.

“한국 사회의 변화는 나에게, 노후를 이 사회에서 보내도 되는지 여부의 문제이기도 하다. 또 차세대에게 어떤 사회를 물려 줄 것인지의 문제이기도. ”

이재명 비판에 다시 나섰으니 나를 공격하는 이들이 많아질 것 같아 공유해 두는 글. 새로 페친이 된 분들께도 자기 소개겸.

비판은 좋지만 정확한 비판이 아니면 의미가 없다.

하는 이에게도 받는 이에게도.

Park Yuha

와세다대학에서 연락이 왔다. <제국의 위안부>에 상을 수여했던 이시바시 탄잔을 기념하는 상 역사가 20년이 되어, 기념전시를 한다고. 미리 허가를 구하는 메일이었는데 당연히 이의가 있을 리가 없다.

이시바시 탄잔은 1950년대 중반에 불과 두달 수상을 지낸 정치가다(언론인에서 출발해 국회의원과 장관등 역임).

그런데 유리케이스에 넣어 전시한다는 말을 듣고 나쁜 기억을 떠올렸다. 작년 여름에 민족문제연구소가 같은 책을 “친일파”책으로 지목해 유리케이스에 넣어 전시하고 영상까지 만들어 퍼뜨렸던 사실.

최근 1,2년 동안 이런 류 사람들이 생각이 갇혀 있고 폭력적이기까지 하다는 걸 꽤 많은 사람들이 알게 되어 다행이지만, 나로선 여전히 겨누어지고 있는 또다른 폭력의 결과를 기다리고 있는 처지라, 그저 웃고 넘길 수 없어 좀 슬프다.

한국 사회의 변화는 나에게, 노후를 이 사회에서 보내도 되는지 여부의 문제이기도 하다. 또 차세대에게 어떤 사회를 물려 줄 것인지의 문제이기도.

그래서 나름 안간힘을 쓰긴 하는건데, 공격자들의 숫자가 훨씬 많고 권력 역시 그들에게 쥐어져 있어서 가끔 아찔해지기도 한다.

이시바시 단잔

이시바시 단잔 石橋 湛山 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 일본의 제55대 내각총리대신 | |

| 임기 | 1956년 12월 23일~1957년 2월 25일 |

| 전임 | 하토야마 이치로 |

| 후임 | 기시 노부스케 |

| 일본의 통상산업대신 | |

| 임기 | 1954년 5월 21일~1956년 12월 23일 |

| 전임 | 아이치 기이치 |

| 후임 | 미즈타 미키오 |

| 총리 | 하토야마 이치로 |

| 일본의 대장대신 | |

| 임기 | 1946년 5월 22일~1947년 5월 24일 |

| 전임 | 시부사와 게이조 |

| 후임 | 가타야마 데쓰 (임시대리) |

| 총리 | 요시다 시게루 |

| 이름 | |

| 본명 | 스기타 세이조 杉田 省三 |

| 신상정보 | |

| 출생일 | 1884년 9월 25일 |

| 출생지 | 일본 도쿄도 |

| 사망일 | 1973년 4월 25일 |

| 정당 | 자유민주당 |

| 종교 | 니치렌슈 |

이시바시 단잔(일본어: 石橋 湛山, 1884년 9월 25일 ~ 1973년 4월 25일)은 일본의 언론인이자 정치가로, 제55대 내각총리대신을 지냈다.

성장

[편집]1884년 9월 25일 도쿄도에서 일련종 승려인 아버지의 장남으로 태어났다. 어머니의 성인 이시바시(石橋)를 따랐으며, 일련종에 입적하며 단잔(湛山)으로 개명했다.[1] 그와 동시에 태어난 직후의 유년기에는 야마나시현에서 거주했었다. 그 후 와세다 대학을 졸업하고 신문사 주필, 사장을 지냈다.

정치가

[편집]제2차 세계 대전 후 일본 사회당이 총선거 출마를 제의했지만 이를 거절했다. 1946년 총선거에서 자유당 후보로 출마했지만 낙선, 요시다 시게루 내각에서 대장대신(제1차 요시다 내각)을 역임했다. 미군의 주둔 경비 분담액 삭감을 요구했다가 경질됐다. 1954년 하토야마 이치로 내각에서 통상산업대신(제1차 하토야마 이치로 내각)으로 취임하여 1955년 11월에 중화인민공화국과 ‘중일수출입조합’의 결성을 지원해 중국과의 무역 궤도에 오르기도 했다.

보수합동 이후 자유민주당 전당 대회에서 근소한 표차로 승리해 자유민주당 총재 겸 제55대 총리가 되었지만, 이듬해인 1957년 2월경 재임한 지 2개월 만에 뇌경색이 발병해 퇴임하였다(공식 발표는 노인성 급성 폐렴). 같은 해 퇴임 후 1957년 10월에 모교인 와세다 대학에서 명예 박사학위(초대)를 받았고, 1959년 9월과 1963년에 두 차례 중국을 방문하여 저우언라이 총리와 회담을 가졌으며, 1964년에 소련을 방문하는 등 중국과 소련의 국교 회복에 앞장서기도 했다. 1963년 중의원 선거에 후보로 출마했지만 낙선하여 정계를 은퇴했다.

주장

[편집]그는 전쟁 전부터 일관되게 일본의 식민지 정책을 비판해 가공 무역 입국론을 주창하였으며, 전후에는 ‘중·일·미·소 평화 동맹’을 주장해 일본 정계에서 활약을 했다.

같이 보기

[편집]각주

[편집]- ↑ “石橋湛山は得度しているが、僧籍はあるか。あるとしたら日蓮宗の僧階は何か。”. 《レファレンス協同データベース》. 国立国会図書館. 2019년 7월 2일. 2024년 7월 13일에 확인함.

외부 링크

[편집]- (일본어) 역대 총리의 사진과 경력 - 이시바시 단잔(수상 관저 홈페이지)

- (일본어) 재단법인 이시바시 단잔 기념재단 홈페이지 보관됨 2009-04-08 - 웨이백 머신

이시바시 단잔

출처 는 열거할 뿐만 아니라 각주 등을 이용하여 어느 기술의 출처인지를 명기 해 주십시오. |

| 이시바시 하야마 이시바시 탄잔 | |

|---|---|

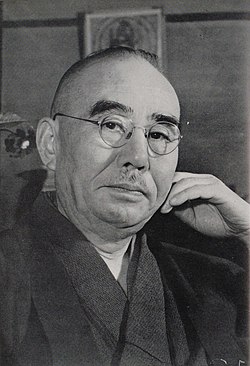

이시바시의 초상화 사진(1951년경) | |

| 생년월일 | 1884년 9월 25일 |

| 출생지 | |

| 몰년 월일 | 1973년 4월 25일 (88세) |

| 사망지 | |

| 출신 학교 | 와세다대학 문학과 졸업 |

| 전직 | 동양경제신보 사 합명사원 |

| 소속정당 | ( 일본 자유당 →) ( 민주 자유당 →) ( 자유당 →) ( 분당파 자유당 →) (자유당 →) ( 일본 민주당 →) 자유 민주당 |

| 칭호 | 종2위 훈일등 욱일 키리하나 다이츠키 명예 박사 (와세다대학· 1957년 ) 권대승정(니치렌종· 1957년 ) 대일본 제국 육군 소위 |

| 배우자 | 이시바시 우메 |

| 자녀 | 장남:이시바시 쇼이치 장녀 :치바 가자 차남 :이시바시 카즈히코 |

| 친족 | 스기타 히노 부(아버지) |

| 기호 |  |

| 내각 | 이시바시 내각 |

| 재임기간 | 1956년 12월 23일 - 1957년 2월 25일 |

| 천황 | 쇼와 천황 |

| 내각 | 이시바시 내각 |

| 재임기간 | 1956년 12월 23일 - 1956년 12월 27일 (총리겸임) |

| 내각 | 제1차 하토야마 이치로 내각 제2차 하토야마 이치로 내각 제3차 하토야마 이치로 내각 |

| 재임기간 | 1954년 12월 10일 - 1956년 12월 23일 |

제2대 물가청 장관 | |

| 내각 | 제1차 요시다 내각 |

| 재임기간 | 1947년 1월 31일 - 1947년 3월 20일 |

| 내각 | 제1차 요시다 내각 |

| 재임기간 | 1946년 5월 22일 - 1947년 5월 24일 |

기타 직업 | |

현제 2구 당선 횟수 6회(1947년 4 월 26일 - 1947 년 5월 17 일 ) | |

( 1924년 - 1928년 ) | |

(1956년 12월 23일 - 1957년 3월 21일) | |

( 이시바시 단잔, 1884년 < 메이지 17년> 9월 25일 - 1973년 < 쇼와 48년> 4월 25일 )는 일본 의 저널리스트 , 정치가 , 교육자 ( 입정대학 학장). 계급 은 육군 소위 (육군 재적시). 위층은 종 2위 . 훈 등 은 훈일 등 .

대장 대신 ( 제50대 ), 통상산업대신 (제 10 · 11 · 12 대), 내각총리대신 ( 제55대 ), 우정대신 (제9대) 등을 역임했다. 총리대신 재임기간은 65일이며 일본 헌법 하에서는 하네다 효 의 64일에 이어 2번째로 짧고 일본 헌정사상에서도 3번째 짧다.

와세다대학 으로부터 법학의 명예 박사(Doctor of Laws)를 받았다(1957년 10월 20일 수여).

개요

[ 편집 ]메이지 국가의 밀리터리즘, 임페리얼리즘은 세계의 추세였다고 해도 간과해서는 안되는 것이 데모 클래시의 양성이라고 한다. 이것에 일본인은 자랑을 기억하라고 말하고 있다.

전전은 ' 동양 경제 신보' 등의 논단에서 국가로서 정상적인 정책으로 간주되기도 했던 제국주의를 일본에는 맞지 않는 것으로 간파해 국제협조를 배경으로 한 무역·과학에 의한 경제안정을 제창했다.

전후에는 ‘중일 서평화동맹’을 주장해 정계에서 활약했다. 보수 합동 후 처음으로 본격적 [ 주석 1 ] 에 실시된 자민당 총재 선거를 제치고 총리 총재가 됐지만 재임 2개월 미만으로 발병해 퇴진했다. 퇴진 후에는 중화인민공화국 과의 국교정상화에 힘을 다했다.

하야마의 사상은 휴머니즘·자유주의이며, 재학중, 다나카 왕당 아래에서 플러그 마티즘의 영향을 받은 것으로부터, “진리와는 항상 인류의 생활의 변화와 함께 변화하는, 결코 천고 불마한 것은 아니다”라고 하는 어록에 보이는 것처럼, 다른 것을 고민하지 않고 절대적인 주의에 빠지다.

전전전 중, 제국주의·군국주의·파시즘을 비판해, 언론의 자유를 표방해, 시민을 중심으로 정한 철저한 민주주의와 리버러리즘을 관통했다고 해도 좋을 것이다.

친아버지는 미노베야마 구원사 제81세 법주 스기타 닛포 이다. 그 관계로, 입정대학 학장에 취임했다.

평생

[ 편집 ]살아남다

[ 편집 ]니치렌 종 스님 · 스기타 쇼맹 횃불 부부의 장남· 성삼 (세이 조 ) [ 주석 2 ] 로서 태어난 [ 1 ] .

친아버지의 맹세는 니치렌 종일치파의 초대 관장인 신이 히사쓰의 문하 에서 [ 2 ] , 현재의 도쿄도 미나토 구 다카나와 의 승교사 에 소재하고 있던 당시 도쿄대교원(현· 립정대학 의 전신)의 조교보( 조수 → 조교 )를 맡고 있었다 [ 3 ] .

어머니·킨은, 에도 성내 의 다다미표 일식을 맡을 정도의 큰 다다미 도매상·이시바시 후지 사에몬의 차녀이다 [ 3 ] [ 2 ] . 이시바시가는 승교사의 유력한 단가 로, 도쿄대교원에 재학중인 맹세와 친해지고 있었다 [ 4 ] . 따라서 야마야마는 어머니의 이시바시 성을 자칭했다 [ 3 ] .

하야마는 3남 3녀 6명 형제 중 장남이다 [ 5 ] . 야마야마의 형제에서는 쇼맹차남의 노자와 요시로도 히로야마와 마찬가지로 고후 중학·와세다대학을 거쳐 동양경제신보사에 입사해 지국장·감사역을 맡고 있다 [ 5 ] . 쇼맹삼남의 쇼쇼는 도쿄대학을 졸업하고, 후지노미야 이치젠지의 주직이 되고 있다 [ 5 ] .

학생 시대

[ 편집 ]1885년 ( 메이지 18년), 아버지·가맹이 고사토야마나시현 미나미거 마군 마사 호무라 (현·동군 후지가와초 ) 에 있는 창후 쿠지 의 주직 으로 돌아가기 위해, 어머니·킨과 함께 고후시 이나 몬(현·고후시 이세 2가)로 이사한다.

1889년 (메이지 22년), 고후시립이나몬 심상 초등학교 에 입학한다. 3학년 때 처음으로 아버지와 동거하게 되어 이나몬에서 약 20km 안에 있는 마스호무라 초등학교로 전학했다.

1894년 (메이지 27년), 맹세가 시즈오카시 의 니치렌 무네모토야마·아오류야마 본 각사 의 주직으로 돌아가게 되어, 야마나시현 나카 거 마군 거울 나카죠무라 (구·동군 와카쿠사무라 → 와카쿠사마치 , 나미남 알프스시 에 편입)에 있는 나가토지 의 주직인 망월 이다. 이후 실질적인 부모와 자식의 관계는 끊어져 몇번이나 편지를 들지만 부모로부터의 대답은 받지 못했다고 한다.

1895년 , 니켄에게 추천되어 야마나시 현립 심상 중학교(후의 고후 중학, 현재의 야마나시 현립 고후 제일 고등학교 )에 진학한다. 하산은 2년 낙제해 7년간 재적한다. 1901년(메이지 34년) 3월에는 고후 중학교장의 히라하라탄이 퇴임하고, 오오시마 마사 타케 가 부임한다 [ 6 ] [ 7 ] . 오오시마는 삿포로 농학교 (현· 홋카이도 대학 의 전신) 제1기생으로서 윌리엄·스미스·클라크 의 가오루를 받은 인물로, 1914년 (다이쇼 3년)까지 고후 중학교장을 맡았다 [ 6 ] . 하야마는 1902년에 고후 중학교를 졸업하기 위해 1년만의 가오루를 받지만, 야마나시는 나중에 '야마나시현립 고후 중학동창회보'에서 오시마와의 만남을 술회하고 자신의 인생관에 큰 영향을 주었다고 한다 [ 8 ] . 만년에 이르기까지 하산의 베개에는 항상 닛렌 유문집과 성경이 놓여 있었다고 한다. 재학 중에는 교우회의 계간지 '교우회 잡지'에 논문을 투고해 검도부에도 입부했다.

『교우회 잡지』는 고후 1교 백주년 기념관 자료실에 수십 권이 소장되어 있으며, 야마야마의 논문을 포함한 호도 현존하고 있다 [ 9 ] . 하야마는 1900년 6월 발행 제8호에서 '이시바시 좌망'의 필명으로 소론 '이시다 삼성론'을 발표하고, 이후 '이시바시성 3' '이시바시성조' '이시바시 히로야마' 등의 이름으로 소론을 발표하고 있다 [ 10 ] . 또 『교우회 잡지』에는 학술부 총회에 관한 보고도 게재되어, 야마야마가 총회에 있어서 영문 낭독·연설, 문장의 낭독·연설 등을 실시하고 있어, 당시부터 정치·역사 등에 관심을 가지고 있었던 것이 확인된다 [ 11 ] . 5학년 때에는 동회의 이사를 맡고 있다 [ 12 ] .

1902년 (메이지 35년) 3월에, 야마나시 현립 제1중학교 를 졸업한다. 중학교를 졸업할 무렵, 가쓰야마 로 개명하고 있다 [ 주석 3 ] . 다음달, 제1고등학교 (현· 도쿄대학 교양학부 ) 수험을 위해 상경한다. 그 때 정칙 영어학교 [ 주석 4 ] 에 다녔다. 그러나 같은 해 7월의 시험은 불합격이었다. 이듬해에 다시 수험하지만 다시 실패하고 와세다 대학 고등예과 의 편입시험을 받고 합격해 9월에 입학했다. 따라서 도쿄에서의 하숙 생활이 시작되었다 [ 13 ] .

저널리스트 시대

[ 편집 ]와세다대학을 졸업하고 1년간 연구과에서 공부한다. 1908년 (메이지 41년) 12월에, 시마무라 다카쓰키 의 소개로 매일 신문사 (구 요코하마 매일 신문이나 구 도쿄 요코하마 매일 신문 으로, 당시는 『도쿄 매일 신문』을 내고 있다.현재의 매일 신문사 와는 무관)에 입사했다.

1909년(메이지 42년) 12월에는 도쿄 아자부의 제1사단 · 보병 제3연대 에 1년 지원병 으로서 입영한다 [ 14 ] . 하야마는 처음 사회주의자 와 오해되어 감시병의 취급을 받지만, 나중에 오해가 풀리고 상관·장교와도 양호한 관계를 쌓아, 그들도 하야마의 '합리성'을 평가했다고 한다 [ 14 ] . 하야마는 사무라이 로 승진해, 1910년(메이지 43년) 12월 1일 군조 로 예비역 편입 [ 14 ] [ 15 ] . 하야마는 입영 중에 군대의 철학에 관심을 갖고 사회생활·단체생활에 대한 순응성의 중시를 통감했다고 한다 [ 16 ] .

1911년(메이지 44년) 1월에 동양경제신보사 에 입사하지만, 같은 해 9월에 견습사관으로서 재입영해, 최종 시험을 거쳐 1913년(다이쇼 2년) 1월 10일에 육군 보병 소위가 된다 [ 14 ] [ 15 ] . 그 후 1916년 여름에 반월간의 기동 연습에 소집되고 있다 [ 16 ] .

1912년 (다이쇼 원년) 11월, 도쿄경제신보사 주간· 미우라 유타로의 매황으로 히가시코마쓰카와 마쓰에 심상고등 초등학교의 교사· 이와이 우메 (우메코)와 결혼한다 [ 17 ] . 우메는 후쿠시마현 니혼마츠 출신의 교사였던 미우라의 아내의 가르침이었다 [ 17 ] .

하야마는 다이쇼 데모 클래시 에서 오피니언 리더 중 한 명으로 ' 민주주의 '를 재빨리 제창한다. 또 삼·일독립운동 을 비롯한 조선 에서의 독립운동에 대한 이해를 나타내거나 제국주의 에 대항하는 평화적인 가공무역입국론을 주창하여 대만·조선·만주의 포기를 주장하는 등( 소일본주의 ) 리버럴한 언론인으로 알려져 있다. 1924년 ( 다이쇼 13년) 12월에 제5대 주간이 되어, 다음해 1월 에는 대표이사 전무(사장제가 되는 것은, 1941년 이후)에 취임한다. 또 같은 해부터 1936년 (쇼와 11년)까지 가마쿠라 초 의회 의원을 맡았다.

1931년 (쇼와 6년)에는 동양경제신보사를 중심으로 한 경제 클럽이 창설된다 [ 18 ] [ 19 ] . 1933년 (쇼와 8년)에는 경제 클럽의 회원에 의해 야마나시 현 미나미토루군 야마나카코 무라 아사히히오카에 「경제 클럽 야마나카코반 산장 동인회 ( 경제촌)」가 만들어져 쇼잔도 야마나카 코반에 야마소를 썼다 .

부하의 다카하시 카메 요시와 함께 경제 논단의 일익을 담당해, 금 해금 에 있어서는 1엔=금 2분(1/5 엔·0.75g. 구평가)에서의 금 본위 제 복귀에 반대해, 실체 경제에 맞추어 통화 가치를 떨어뜨린 뒤에서의 복귀(신평가 해금)를 카츠 타 사다케 타나리 아키라 와 호리에 귀일 , 오쿠라 대신으로 금해금을 구평가로 실시하는 이노우에 준노스케 와 논쟁하고 있다. 행정에서는 중앙집권 ·화일주의· 관료주의 와의 속별을 주장했다.

일중전쟁 발발부터 패전에 이르기까지 ' 동양경제신보 ' 잡지에서 장기전화를 계명하는 논진을 하고 있다. 이 잡지는 서명 기사를 쓰는 것이 어려웠던 많은 리베라리스트( 키요자 와 쇼라 )에게도 익명으로의 논설의 장을 제공한다. 이시바시와 익명 집필자의 논조는 항상 냉정한 분석에 근거하고 있고, 또한 완곡·은미에 독자를 계몽하는 특징을 가지고 있었기 때문에, 잡지는 정부· 내무성 으로부터 항상 감시 대상으로 되어 잉크나 종이의 배급을 크게 제한되었지만, 폐간은 면했다.

태평양 전쟁 에서는 차남 카즈히코가 소집되어 전사했다. 또 전쟁 말기에는 연합국의 전후구상에 자극을 받아 전후연구의 중요성을 이시 도소타로 장상에게 진언하고, 그에 의해 설립된 대장성 전시경제특별조사실에서 경제학자나 금융관계자와 함께 전후연구를 했다 [ 21 ] . 전시 경제 특별 조사실의 자료는 나고야 대학 대학원 경제학 연구과 부속 국제 경제 정책 연구 센터 정보 자료실의 웹 사이트 에서 열람 가능하다.

패전은, 인쇄 공장 소개처의 아키타현 히라카군 요코 테마 치 (현, 요코테시 )에서 맞이했다 [ 22 ] . 히토야마는 요코테쵸민이나 아키타 시민 에게 강연을 시도해, 연합군의 대일 방침과 일본 경제의 전망에 대해 이야기해, 인심의 고무에 노력해, 1945년 (쇼 와 20년) 8월 25일 에는, 논설 「갱정 일본의 진로~ 의 부활을 주창했다 [ 22 ] . 그는 무역의 자유만 있으면 영토축소의 불이익은 극복할 수 있다고 하고 산업부흥계획을 세우고 그것을 실행하라고 설설하였고, 정치면에서는 오카조의 맹세문 과 긴정헌법 으로 돌아갈 수 있다고 주장했다 [ 22 ] . 10월 13일 '동양경제신보사론'에서 '야스쿠니신사 폐지의 의'를 논하고 야스쿠니신사 의 폐지를 주장했다 [ 22 ] [ 23 ] .

도쿄 재판 에서는 GHQ ·검찰 측이 다카하시 시청 의 경제 정책이 전쟁에 연결되었다고 주장했지만, 이에 대해 이시바시는 변호를 했다 [ 24 ] . 이시바시는 다카하시 시청의 정책은 디플레이션 불황을 탈출하기 위한 정책이며, 군비 확장에는 연결되어 있지 않은, 메이지 이후의 정책과 군비 확장의 정책은 다르다고 주장했지만, 재판에서는 채용되지 않았다 [ 25 ] .

정치에

[ 편집 ]하야마는 자신의 경제부흥계획의 실현을 위해 전후 정치에 들어가기로 결의했다 [ 22 ] . 1946년 (쇼와 21년) 4월 10일에 행해진 제22회 중의원 의원 총선거 에 있어서, 일본 사회당 으로부터 권유를 받는 것도 이것을 거절하고, 일본 자유당 공인으로 도쿄도 제2구(대선거구) 로부터 입후보했다 [ 26 ] . 스스로의 계획 실현에 적합한 정당은 하토야마 이치로가 이끄는 일본 자유당이라고 생각했기 때문이었다 [ 22 ] . 하야마는 이 선거에 낙선하지만, 같은 해 5월 22일에 성립한 제1차 요시다 내각에 오쿠라 대신 으로 입각 했다 [ 22 ] .

오조 장관 재임시에는 디플레이션을 억제하기 위한 인플레이션을 진행해 경사 생산 ( 석탄 증산의 특수 촉진)과 부흥 금융 금고 의 활용을 특징으로 하는 '이시바시 재정'을 추진했다.

그리고 전시 보상 채무 중단 문제, 석탄 증산 문제, 진주 군 경비 문제 등으로 GHQ 와 대립한다. 진주군 경비는 배상비로 일본이 부담하고 있으며, 골프장과 저택건설, 사치품 등의 경비도 포함하고 있어 일본 국가예산의 3분의 1을 차지하고 있다. 이 엄청난 부담을 줄이기 위해 이시바시는 요구했다. 미국은 외국의 평판을 신경쓰는 것과 이후 통치를 원활하게 진행시키는 것을 고려해 일본의 부담액을 20% 삭감하게 되었다.

공직 추방

[ 편집 ]전승국 미국에 용기 있는 요구를 한 이시바시는, 국민으로부터 “ 심장대신 ”이라고 불리기도 미국에 미움받아, 1947년 (쇼와 22년)에 제23회 중의원 의원 총선거 로 시즈오카 2 구(중선거구)로부터 당선했지만, 공직 추방령 으로 GHQ에 의해 공직 추방 되었다 이 공직 추방은 요시다 시게루가 관여 하고 있다고 말했다. 1951년 (쇼와 26년)의 추방 해제 후는, 요시다의 정적이었던 자유당 ·하토야마파의 간부로서 타도 요시다로 움직였다. 이 시기에 입정 대학 에서 간청되어 학장으로 취임했다.

공직 추방에서 복귀

[ 편집 ]

1954년 (쇼와 29년)의 제1차 하토야마 내각 에서 통상산업대신 에 취임했다. 1955년 에는 상공위원회 위원 나가 타 나카가쿠에이 아래 전후 재벌해체 의 근거법령의 하나였던 과도경제력 집중배제법을 독점 금지법 으로 대체 하는 형태로 폐지하였다 . 1955년 (쇼와 30년) 11월에는 일중 수출입 조합 의 결성을 지원했다.

이시바시는 중화인민공화국, 소련 과의 국교회복 등을 주장했지만 미국의 맹반발을 받는다. 미국 존 포스터 덜레스 국무장관은 “중공(중화인민공화국), 소련과의 통상관계 촉진은 미국 정부의 대일 원조 계획에 지장을 초래한다”고 통고해 왔다. 이 미국의 강경 자세에 동요한 하 토야마 이치로 총리에 대해 이시바시는 “미국의 의향은 무시합시다”고 말했다.

같은 해 11월 15일 의 보수 합동 에 의해 하토야마의 일본 민주당 과 요시다로부터 계승한 오가타 타케토라 의 자유당이 합동해 자유민주당 이 결성되어 이에 이시바시도 참가했다.

총리 총재

[ 편집 ]

1956년 (쇼와 31년) 10월 19일 에 일본과 소비에트 연방이 닛소 공동 선언 에 의해 국교 정상화하는 것도, 같은 해 11월 2일, 하토야마 총리가 사임을 표명. 이에 따라 같은 해 12월 14일 자민당 총재 선이 실시됐다. 이시바시는 한층 더 중화인민공화국 등 다른 공산권 과도 국교 정상화하는 것을 주장해 하토야마파 일부를 이시바시파로 이끌고 입후보했다. 이시바시 외에 미국 추종을 주장하는 기시 노스케 , 그리고 이시이 코지로 가 입후보했다. 당초는 기시 우위로, 1회 투표에서는 기시가 1위였지만, 이시이 미츠 지로와 2위·3위 연합을 맺은 결선 투표에서는 이시바시파 참모의 이시다 히로에이 의 공적도 있어, 해안에 7표 차이로 경쟁해 이겨 총재에 당선, 12월 23일 에 내각 총리대신에게.

그러나, 전술한 바와 같은 총재선이었기 때문에 기시 지지파와의 덩어리가 남아, 한층 더 이시바시 지지파 내부에 있어서도 각료나 당 임원 포스트의 공수형 난발이 행해져, 조각이 난항했기 때문에, 이시바시 자신이 일시적으로 많은 각료의 임시 대리·사무 취급을 겸무해 발족 했다 . 친중파이기도 한 이시바시 정권의 수립에 의해, 일본을 반공의 요새로 하기 위해 해안을 바라고 있던 미국 대통령 드와이트·D·아이젠하워 는 늑대 끌었다고 한다. "당내 융화를 위해 결선투표로 대립한 기슭을 이시바시 내각의 부총리로 처우해야 한다"는 의견이 강했기 때문에 이시바시 내각 성립의 입역자였던 이시이의 부총리가 없어져 부총리에는 기시가 취임했다.

내각 발족 직후에 이시바시는 “전국민을 포괄하는 종합적인 의료보장”을 연설한 하토야마의 노선을 계승해, 같은 해 1월 8일에 국민 모두 보험을 목표로 하는 것을 각의 결정 [ 28 ] [ 29 ] 하는 등 복지 국가 건설을 한층 더 구체적으로 경제정책에서는 이케다 용인을 오쿠라 대신에게 발탁하여 ‘1000억엔 시책, 1000억엔 감세’를 내세웠다. 이는 당시의 예산 규모로 하면 지극히 적극적인 예산이며, 소득 감세의 한편으로, 시책은 도로(수송)·주택에 중점을 둔 것으로, 성장 과정의 장해 제거에 의해 더욱 성장을 불러일으키는 순환 작용을 의도한, 고도 성장기의 재정의 원형이라고도 할 수 있는 예산이었던 반면, 단기적으로는 되었다 [ 30 ] . 전국 10개소를 9일간 돌린다는 유설행각을 감행, 스스로의 신념을 말함과 동시에 유권자의 의견을 적극 들었다. 같은 해 1월 25일, 귀경한 직후에 집의 목욕탕에서 쓰러졌다. 가벼운 뇌경색 이었지만 보도에는 "유설 중에 찢어진 감기를 가라앉히고 폐렴을 일으킨 뒤 뇌경색의 징후도 있다"고 발표했다. 부총리격의 외상으로 각내에 맞이하고 있던 기시노스케 가 즉시 총리 임시대리 가 되었지만, 2개월의 절대 안정이 필요하다고 의사의 진단을 받아, 이시바시는 “나의 정치적 양심에 따른다”라고 퇴진했다. 1957년 (쇼와 32년)도 예산심의라는 중대 안건 속에서 행정부 최고책임자인 총리가 병요양을 이유로 스스로 국회에 출석 [ 주석 5 ] 해 대답할 수 없는 상황 에서의 사임 표명에는 야당 조차 호의적이었으며 [ 주석 6 ] 이시바시의 깨끗함 에 감명을 받아 " 정치가 는 많고 싶다"고 말했다. 이시바시의 총리 재임 기간은 65일로, 히가시 쿠나미야 치히코왕 하네다孜에 이은 역대에서 3번째 짧다. 일본 헌법 하에서 국회에서 한 번도 연설과 답변 을 하지 않은 채 퇴임한 유일한 총리가 됐다. 후임의 총리에는 기슭이 임명되어 거주 내각 으로서 제 1차 기슭 내각이 탄생했다.

이시바시는 쇼와 초기에 '동양 경제 신보'에서 폭한에 저격되어 ' 제국의회 '에 참석할 수 없게 된 당시 하마구치 유코 총리에 대해 ' 의회 운영 에 지장을 입었고 깨끗하게 퇴진할 것'이라고 하는 퇴진을 권고 하는 사설을 쓴 적이 있었다 . 만약 국회에 나갈 수 없는 자신이 총리를 속투하면 당시 사설을 읽은 독자를 속이는 사태가 된다고 생각한 것이다.

퇴진 후

[ 편집 ]다행히 뇌경색의 증상은 가볍고, 약간의 후유증은 남았지만, 이시바시는 곧 정치 활동을 재개할 때까지 회복했다.

1959년 (쇼와 34년) 9월, 기시보다 「동맹국 미국의 의사에 반하는 행위이며, 일본 정부와는 전혀 관계없는 것으로 한다」라고 견제되면서도 중화 인민 공화국 을 방문했다. 전 총리·중의원 의원이라고 해도 정부의 일원이 아닌 이시바시는 방문한 지 며칠은 좀처럼 정상과 만날 수 있는 목표가 없었지만 협상에 고생 끝에 같은 달 17일 주은래 총리 와 의 회담이 실현됐다. 냉전구조를 깨고 일본이 그 서두르는 일중미 서평화동맹 을 이시바시는 주장했다. 이 주장은 아직 유엔의 대표권을 갖고 있지 않은 공산당 정권에 있어서 국제사회에의 발판이 되는 것으로서 매력적이며, 주는 이 제안에 동의했다. 주는 대만 ( 중화민국 )에 무력행사를 하지 않으면 이시바시에 약속했다. “일본과 중국은 양국민이 손을 잡고 극동과 세계의 평화에 공헌해야 한다”는 이시바시·주공동 성명을 발표했다. 1960년 (쇼와 35년) 대륙 중국과의 무역이 재개되었다. 이 성명이 나중에 일중 공동성명 에 연결되었다고도 한다.

그 후도 소수파벌이면서 이시바시파의 소매로 영향력을 갖고, 해안이 주도한 미·일 안보조약 개정에는, 본회에서의 의결을 결석하는 등, 비판적인 태도를 취해 자민당내 비둘기파 의 중진으로서 활약했다.

1963년 제30회 중의원 의원 총선거 에서 자민당은 고노이치로 의 전 비서관인 키베 카쇼 를 새롭게 공인. 정수 5의 선거구를 자민당 공인 후보자 4명이 싸워, 이시바시는 다음점에서 낙선. 그대로 정치권을 은퇴했다.

1966년 2월, 사지에 마비를 느끼고 성로가 병원 에 입원, 주치의는 히노하라 시게아키가 맡았다. 같은 해 11월 자민당 간부 오오쿠보류지로의 장례 에 참렬한 것을 마지막으로 외출 기록은 없다. 1968년 3월에는 입정대학 학장을 물리치고 일체의 사회적 활동에서 은퇴했다. 1970년 2월에도 다시 폐렴 으로 성로가병원에 입원해, 그 후는 가마쿠라의 딸집이나 신주쿠구 나카오치아이의 자택에서 요양하게 된다.

1967년 10월 20일에 요시다 시게루가 사망 하고, 당시 존명중의 내각 총리대신 경험자로서는 최연장이 된다.

1971년 7월에는 미국 대통령의 특사 헨리 키신저 가 방중해 주은래 와 회담하면 미중 대화를 지지하는 메시지를 발표하고 있다. 또 이듬해 1972년 7월에는 다나카 각영내각이 성립하여 중국 교 정상화 에의 기운이 높아지고 있었지만, 다나카는 방중 3일 전인 9월 22일에 나카오치아이의 이시바시야케를 방문해 이시바시로부터 주은래로 향하는 서한을 맡고 있다 [ 32 ] . 다나카 방중의 결과, 일중국교 정상화가 성립하면, 이시바시는 이것을 축하하는 메세지를 발표하고 있다.

그 후는 병상이 악화되어, 1973년 4월 25일 오전 5시에 뇌경색 때문에 [ 33 ] 도쿄도내의 자택에서 사망 [ 22 ] . 향년 90(만 88세몰). 사거 시점에서 내각총리대신 경험자로서는 최연장이었다(이시바시의 사거에 따라 최연장은 카타야마 테츠가 된다 .

약년보

[ 편집 ]

- 1884년 (메이지 17년)

- 1885년 (메이지 18년)

- 1894년 (메이지 27년)

- 1895년 (메이지 28년)

- 4월 - 야마나시 현립 심상 중학교 에 입학.

- 1902년 (메이지 35년)

- 3월 - 세이조를 쓰야마 로 개명한다. 야마나시현립 야마나시현 제1중학교 를 졸업.

- 1903년 (메이지 36년)

- 9월 - 와세다대학 고등예과 에 편입.

- 1904년 (메이지 37년)

- 1907년 (메이지 40년)

- 1908년 (메이지 41년)

- 1909년 (메이지 42년)

- 1910년 (메이지 43년)

- 11월 - 군조 로 승진해 제대.

- 1911년 (메이지 44년)

- 1912년 (다이쇼 원년)

- 1913년 (다이쇼 2년)

- 1916년 (다이쇼 5년)

- 11월 - 동양경제신보사의 합명사원 으로 선정된다.

- 1917년 (다이쇼 6년)

- 1924년 (다이쇼 13년)

- 1925년 (다이쇼 14년)

- 1935년 (쇼와 10년)

- 9월 - 내각 조사국 위원에게 맡겨진다.

- 1940년 (쇼와 15년)

- 11월 - 동양경제연구소를 설립하여 소장 및 이사로 취임.

- 1941년 (쇼와 16년)

- 2월 - 동양경제신보사의 사장제 신설에 따라 대표이사 사장으로 취임.

- 1945년 (쇼와 20년)

- 3월 - 도쿄 대공습 에서 잔디의 집이 소실.

- 1946년 (쇼와 21년)

- 3월 - 야마가와 균제창의 민주인민연맹 돌보기인회에 참가.

- 4월 - 전후 첫 중의원 의원 총선거 에 입후보해 낙선.

- 5월 - 제1차 요시다 내각의 오쿠라 대신 에 취임.

- 1947년 (쇼와 22년)

- 1951년 (쇼와 26년)

- 6월 - 공직 추방이 해제되어 자유당 으로 복당.

- 1952년 (쇼와 27년)

- 12월 - 입정 대학 학장으로 취임.

- 1953년 (쇼와 28년)

- 3월 - 정책심의회 회장으로 취임.

- 1954년 (쇼와 29년)

- 11월 - 키시신스케 와 함께 자유당에서 제명처분을 받는다.

- 12월 - 제1차 하토야마 내각 의 통상산업대신 으로 취임한다.

- 1956년 (쇼와 31년)

- 1957년 (쇼와 32년)

- 1959년 (쇼와 34년)

- 1963년 (쇼와 38년)

- 1964년 (쇼와 39년)

- 9월 - 소련을 방문.

- 1968년 (쇼와 43년)

- 3월 - 입정대학 학장을 퇴임.

- 1973년 (쇼와 48년)

인물

[ 편집 ]사상·평론

[ 편집 ]메이지 천황 과 메이지 시대 를 기념한 메이지 신궁 건설 계획에 있어서.

제1차 대전 참전(독일에의 개전)과 대지 21 케조 요구 에 대해서

고배는 우리 정부 당국 및 국민의 외교에 처하는 태도 행동을 보고 우려에 참을 수 없는 것이 있다. 그 중 하나는 노골적인 영토 침략 정책의 감행이고, 둘은 경박한 거국 일치론이다. 이 두 사람은 세계를 꼽고 우리 적이 하는 것이며, 그 결과는 제국 백년의 화근을 긁는 것으로 말해야 한다. ~영국이 독일을 향해 전쟁을 선포하자, 우리 국민은 일제히 일어나 논하고 엎드려, 독일이 칭다오에 근거하는 것은 동양의 근근이다. 일영동맹의 의에 의해 독일을 구축하는 것, 남양의 독령을 탈취하는 것, 제국의 판도를 펼치고 대를 이루는, 이때 있어라고. 당시 고배는 그 불가를 절언했지만, 아사노를 들고 고배의 설에 귀를 기울이지 않고, 드디어 독일과 개전의 불행을 하게 되어, 수천의 인명을 살상한 후에, 이러한 영토를 유지하기 위해 상당히 큰 육해군의 확장이 필요할 뿐, 독미의 대반 함락은 세누카를 위태롭게 한다. 실로 대독개전은 최근에 있어서의 우리 외교 제일착의 그리고 되돌아볼 수 없는 대실책이며, 그러나 이것에, 생각하지 않는 영토 침략 정책과, 경박한 거국 일치론의 생산물이라고 말해야 한다. 대지담판은 독일과 개전하여 칭다오를 잡은 것에서 실을 당겨 나온 실책이지만, 그 우리 제국에 긁어내는 숙근에 이르러 더욱 중대하다. 우리 요구가 많이 관철하면 할수록 세인은 이를 대성공으로 축배를 꼽을 것이다. ~이번 사건으로 우리나라가 지나 및 독일의 심한을 살 수 있다는 것은 물론, 미국에도 불편을 일으킨 것은 다투지 않는 사실이다. 한때 세계가 일본의 손으로 러시아의 머리를 두드리게 한 것처럼, 이들 국가는 일영동맹의 파기를 시작해, 몇 나라를 하고, 일본의 머리를 두드리게 하고, 일본의 입장을 전복시키거나, 아니면 연합하여 일본의 먹이를 빼앗는 계단에 가는 것이 아닐까. 그 경우는, 이번에 얻은 물건의 상실만으로는 도저히 끝나지 않고, 일체의 먹이를 원래도 아이도 없고, 거론될 것이다. 이에 고배의 대지외교를 통해 제국 백년의 근근을 긁어내는 것으로서 아슬아슬할 수 없는 곳이다.— 다이쇼 4년( 1915년 ) '동양경제' 사설

일절 버리는 각오

우리나라의 전반사는 소욕에 사로잡혀 있는 것이다. 뜻이 작은 일이다. 옛날 무욕을 설레게 오해당한 수많은 대사상가도 실은 결코 무욕을 설한 것이 아니다. 그들은 단지 큰 욕심을 전했다. 대욕을 채우기 위해서, 소욕을 버려라고 가르친 것이다. ~ 만약 정부와 국민에게, 모두를 버리고 거는 각오가 있다면, 반드시 우리에게 유리하게 이끌 수 있을 것이다. 예를 들어, 만주를 버리고, 산동을 버리고, 그 지나가 우리나라로부터 받아들이고 있다고 생각할 수 있는 일체의 압박을 버린다. 또 조선에 대만에 자유를 용서한다. 그 결과는 어떻게 될까. 영국이든, 미국이든, 매우 곤경에 빠질 것이다. 왜냐하면 그들은 일본에 걸친 것처럼 자유주의를 채택하고는 세계에서 그 도덕적 지위를 유지할 수 없게 되기 때문이다. 그 때에는 세계의 소약국은 일제히 우리나라를 향해 신뢰의 머리를 내릴 것이다. 인도, 이집트, 페르시아, 아이티, 기타 열강속 영지는 일제히 일본의 대만·조선에 자유를 용서한 것처럼, 우리에게도 자유를 용서하라고 소란스러울 것이다. 이것 실로 우리나라의 지위를 9지의 바닥보다 9천 위에 올려, 영미 그 외를 이 반대의 지위에 두는 것이 아닐까.— 다이쇼 10년( 1921년 ) '동양경제' 사설

중앙집권에서 분권주의로

원래 관료가 국민을 지도하자는 혁명시대의 일시적 변태에 불과하다. 국민일반이 한 사람 앞에 발달한 후에는 정치는 필연적으로 국민에 의해 이루어져야 하며, 장교는 국민의 공종으로 돌아가야 한다. 정치가 국민 스스로의 손에 돌아간다고는, 하나는 가장 자주 그 요구를 달성할 수 있는 정치를 실시해, 하나는 가장 자주 그 정치를 감독할 수 있는 의미에 틀림없다. 이 때문에 정치는 가능한 한 지방분권이어야 한다. 가능한 한 그 지방지방의 요구에 응할 수 있어야 한다. 현재 활사회에 민완을 체포하고 있는 가장 우수한 인재를 자유롭게 행정의 중심에 설 수 있는 제도여야 한다. 여기에 기세, 지금까지의 관료적 정치에 대해서의 중앙 집권, 화일주의, 관료 만능주의(특히 문관 임용령)라고 하는 제도는 근본적 개혁의 필요에 참을 수 밖에 없다. 이제 우리나라는 모든 방면에 몰려왔다. 그러나 이 국면을 타개하고, 다시 우리 국운의 진전을 도모하기 위해서는, 고배가 지금까지 반복할 수 있듯이, 이른바 제2유신을 필요로 한다. 제2유신의 첫걸음은 정치의 중앙집권, 획일주의, 관료주의를 파괴하고 철저하게 하는 분권주의를 채용하는 것이다. 이 주의하에 행정의 일대개혁을 하는 것이다.— 다이쇼 13년( 1924년 ) ‘동양경제’ 사설

경제학자인 다나카 히데토미 는 “이시바시 하야마의 소국주의는 정부·일본은행의 적절한 정책 운영으로 일본의 잠재성장을 서포트해 나가겠다는 리플레 정책의 입장을 기초로 하고 있었다”고 지적하고 있다 [ 35 ] . 다나카는 “『리플레의 경제학』은 소국주의적이며, 자국의 정책에 의해 국내의 경제·사회 문제를 해결해, 타국을 정책에 이용하지 않고 불간섭으로 인근 제국과 우호를 도모하는 방책이라고 할 수 있다”라고 지적하고 있다 [ 35 ] .

헌법과 군대

[ 편집 ]일본 헌법 과 군대가 있는 곳을 둘러싼 언동은 시대 상황에 따라 몇 가지 변천이 있다.

1946년 (쇼와 21년) 3월에 「헌법 개정 초안을 평가한다」로, 일본국 헌법 에 관해서는 헌법 구조 에 해당하는 초안 제2장의 전쟁 포기를 「최초 일본은 패전국에서도, 4등, 5등도 아니고, 영예로 빛나는 세계 평화의 일등국, 예전 일본에 '우리를 이긴 통쾌한 일이 있을까'라고 평가했다.

하지만 1950년 (쇼와 25년)경부터는, 자위군 설치의 주장이나 공산·사회주의와의 대결 자세(후에 스스로 폐고한 「제3차 세계 대전과 세계 국가」)를 선명하게 해, 정치가로서도 「반요시다」 노선에 서, 헌법 개정・재군 비론자로서 활동했다. 같은 시기에는 "파국적인 제3차 세계대전이 싫다면 거기(각국의 군비 전폐)까지 가야 하지 않아"라고 안 쓰고 "그 경우는 나라를 잃어도 좋다는 각오를 하지 않으면 굉장히 할 수 없다"(1952 동양경제신보 "문제를 받은 채로")와 현실과 이상 계명하고 있다. 한편 사적으로 쓴 일기 중에서도 1950년의 기술로 "오늘 세계에 무군비를 자랑하는 것은 병이 가득한 사회에서 의약을 배척하는 혹은 미신"이라고 비무장 중립 의 주장을 공적인 발언 이상으로 신앙에 평하고 있다.

1953년 총선 에서는 하토야마 자유당의 정책위원장으로서 정책을 정리해 '헌법을 국정에 적합하도록 개정', '전쟁 부정의 정신은 국책으로 존치하지만 전쟁 발생 방지를 위해 자위군을 조직한다' 등을 명기했다. 이것은 후년의 “나라로서의 군비를 가지지 않고 국제 분쟁을 무력으로 해결해 나가는 것이 아니라고, 세계에 선언한 것은… 인류 최고의 선언이라고 믿고 있다. 잡힐 때까지 잠시 정지한다'는 상태'라는 주장(1966'중소기업')에도 합치한다.

1957년 (쇼와 32년), 총리에 취임한 이듬해 신춘 특대호의 '동양경제' '이시바시 히로야마 많이 말한다'에서는 ' 유엔 에 대해 의무를 진다는 것은 군비라는 것도 생각할 수 있다'며 동시기의 '프레스 클럽 연설 초고'에서는 '세계의 실정으로 판단하여, 백성은 지는 것이라고 믿습니다. 다만 동고 속에서 “인류를 구원하려 한다면 우리는 군비확충 경쟁을 정지하고 전쟁을 멸종해야 한다”고 냉전의 평화해결과 군축을 주장했다 [ 36 ] .

미소일중평화동맹을 제창하고 나서는 장래의 이상을 말하면서이지만, 다시 평화헌법 의 의의를 강조(「이케다 외교 노선에 바란다」)하면서, 각국의 군비가 아닌 국제 경찰군에 의해 평화를 지키는 「세계 연방」 실현에의 노력을 설고 있다(「일본 방위론」).

이시바시는 후년 “나의 전쟁 반대론에는, 이굴의 밖에, 실은 이(군대 시대의) 실탄 연습의 실감이 강하게 영향을 주고 있었다고 생각한다” “만약 세 사람이 모두 전쟁을 하듯 가까이에 생각하면, 경률인 전쟁론은 흔적을 끊임없이 틀림없다”(「아야마 회상」) 전쟁을 혐오한 쇼잔이지만, 그에게 있어서의 군대 체험은, 평화에 대한 사색이나 공공 생활의 훈련으로서 참된 것이었던 것 같다.

헌법은 국민에게 의무를 짊어야 하는가, 하는 논의에 관해서는, 전제독재에 대항하기 위해 주권을 억제하려고 했던 「19세기의 헌법」으로부터의 탈각을 말해, 민주주의 국에서는 국민이 권리를 가지는 이상은 의무를 자각해야 한다고 주장했다. “의무의 규정에 주밀하지 않은 헌법은 진정으로 민주적인 것으로는 말할 수 없다”고 헌법에 있어서의 의무규정의 충실을 바랐다 [ 37 ] .

에피소드

[ 편집 ]이시바시가 총리를 퇴진했을 때의 청결은 국민 [ 누구? ] 에게 높이 평가되는 경우가 많지만 변호사 마사키 히로시 는 “(사적인 감정으로) 공무(총리의 지위)를 포기했다”고 엄격히 비판하고 있다. 원래 자민당 총재선에서 1위 우위였던 기시신스케 후보의 당선을 막으려고, 이시바시 후보와 이시이 미츠지로 후보가 2위·3위 연합을 맺은 경위가 있다. 이시바시 총리 총재가 탄생하자, 기시는 각내에 부총리격의 외상 으로 맞이해, 이시이는 각외에 머물렀다. 겨울철에 자신의 컨디션을 고려하지 않은 유설을 한 이시바시는 정권 발족 후 감기에 걸려 잠자는 의사에게 절대 안정 진단을 받는다. 이 때 선거 연합 상대인 이시이에 총리 총재직을 맡기는 대신 이시바시는 해안에 총리 임시 대리를 선양해 기시 총리 총재가 평화리에 탄생했다. 예산심의가 눈앞임에도 불구하고 자신의 불안감으로 인해 잠들어 무거운 책임이 있는 총리로서 첫 국회에서 한 번도 연설이나 대답을 할 수 없는 채 수상 퇴진하겠다는 어리석음을 국민에게 노출시켰으며, 차기 총리 총재를 총리의 재치에 당하지 않고, 라는 이념도 반고로 했다는 것이다[ 요 설명 ] .

그 후 동양경제신보사에서 이시바시의 '전집' [ 주석 9 ] 이 제작될 때 편집자는 전집 월보 집필을 마사키에게 의뢰했다. 일찌기 이시바시의 부하이기도 한 그 편집자는 [ 누구? ] , 이시바시에의 예찬 일색의 기사를 모은 것은, 한쪽의 의견에 치우치지 않는 언론의 필요성을 주창해 온 이시바시의 신념에 반한다고 생각한 것이다. 마사키가 쓴 이시바시에 대한 비판은 그대로 게재되었다. [ 독자 연구? ]

소연이 깊은 야마나시현 고후시 에는 2007년 5월, 사설의 야마나시 평화 박물관·이시바시 히로야마 기념관이 개관 했다 [ 39 ] [ 40 ] .

기타

[ 편집 ]1952년 (쇼와 27년) 12월 1일부터 1968년 (쇼와 43년) 3월 31일까지 입정대학 의 학장 을 맡고 있다 [ 41 ] .

영전

[ 편집 ]- 1964년 (쇼와 39년) 4월 29일 : 훈이치 등 욱일 대선장 [ 42 ]

- 1973년 (쇼와 48년) 4월 25일 : 서· 종2위 , 훈이치 등 욱일 키리하나 오츠키 쵸 추증 [ 43 ]

가족·친족

[ 편집 ]스기타가

[ 편집 ]- 생가

이시바시가

[ 편집 ]자가( 도쿄도 )

- 아내· 우메 ( 이와이 존기 의 삼녀, 이와이 존신 여동생

- 장남· 쇼이치 ( 이시바시 히로야마 기념 재단 이사장, 미쓰비시 은행원

- 장녀·카코 (주 멕시코 대사 지바 아키라 의 아내, 1916년생, 우타코 모두 [ 49 ] )

- 차남 와 히코 - 퀘젤린 섬에서 전몰 [ 53 ] .

기타 친척

[ 편집 ]- 야마나시 카츠유키 진 (해군 대장)

- 혼고보 타로 ( 육군 대장 )

- 이토 타다베이 (2대) ( 이토 타다 시 재벌 2대째 당주) 등

평가

[ 편집 ]스즈키 유키오의 『閨閥 결혼으로 굳어지는 일본의 지배자 집단』(1965년) 하지만 눈길을 끈다 . 또 장녀의 남편 치바 아키라 가 외교관 으로 알려져 있었다 .

저서(주로 몰후간)

[ 편집 ]평론집

[ 편집 ]- 이시바시 히로야마 전집(전 15권, 전집 편찬 위원회 편, 동양 경제 신보사, 1970-72년), 별권 “이시바시 히로야마 사진보”(1973년)

- 신판 「이시바시 히로야마 전집」(전 16권, 동상, 2010-11년), 증정권은 제15권, 최종권은 보권

- 이시바시 히로야마 평론집 ( 마츠오 존토 편 , 이와나미 문고, 1984년, ISBN 4-00-331681-9 /와이드판 1991년, ISBN 4-00-007005-3 )

- 소일본주의-이시바시 히로 야마 외교 논집

- 이시바시 히로 야마 평론 선집

- 리베라리스트의 경종 이시바시 히토야마 저작권 집 1- 경제론

- 이코노미스트의 면목 이시바시 히 토야마 저작집 2- 경제론

- 대일본주의와의 투쟁 이시바시 히로야마 저작집 3- 정치 · 외교론

- 개조는 진심으로 이시바시 히토야마 저작집 4- 문예 · 사회 평론

- 하야마 요시모토 지금이야말로, 자유주의, 재흥하라. (후나바시 요이치 편, 동양경제신보사, 2015년). 논설 70편을 선택해 해설.

회상록・일기

[ 편집 ]- 하야마 회상 ( 이와나미 문고(해설 나가사오 ), 1985년 12월, ISBN 4-00-331682-7 ). 초판은 매일 신문사, 1951년

- 하야마 좌담 (이와 나미 서점 <동시대 라이브러리>, 1994년 2월, ISBN 4-00-260173-0 )

- 이시바시 히로야마 히로야마 회상 (인간의 기록 47:일본 도서 센터 , 1997년 12월, ISBN 4-8205-4290-7)

- 이시바시 하야마 일기 (상하·2권조, 이시바시 쇼이치· 이토 다카시 편, 2001년 3월, 미스즈 서방 , ISBN 4-622-03676-2 )

- 상권: ISBN 4-622-03677-0 , 하권: ISBN 4-622-03678-9 . 1945년 1월 1일부터 1957년 1월 23일까지의 일기.

관련작품

[ 편집 ]영화

각주

[ 편집 ]주석

[ 편집 ]- ↑ 1956년 4월 자유민주당 총재선거는 사실상 신임투표였다.

- ^ 쇼야마의 ' 내 이력서 '에 의하면 "유명은 세이조로 불리며 애칭은 세이짱이었다. "착일에 세 번 고가 몸을 생략한다"는 논어 의 유명한 말에서 나온 문자이다"라고 말하고 있다.

- ^ 쇼야마의 ' 내 이력서 '에 의하면, "아버지가 젊어서 제자들이 들어간 야마나시현의 창복사라는 니치렌종의 사원에는 예로부터 돈의 글자를 이름에 붙인다면 내가 있었다. 아버지는 맹세라고 칭해, 나도 이 이유로 중학을 졸업할 무렵."

- ^ 湛山は『湛山回想』の中で、「明治三十五年三月、中学を卒業すると、東京に出た。六月か、七月かにある第一高等学校の入学試験を受けるためであった。…神田錦町の正則英語学校に通った。…ここで私は、入学試験の準備をすることにした。しかし私は、この学校に来てみて驚いた。…大きな教室に、生徒はげたばきのままで雑然と入り込み、出席簿をつけるでもない。人気のある先生の時間には、あふれて、立っている生徒もある。かと思えば、ある先生の時間には、数えるほどしか出席者がない。しかも講義の途中でさっさと持ち物をかたづけて帰って行く生徒もある。いなか者の私は、これでも学校かとあきれたのである。…入学試験準備のための、そのころの学校は回想してみても愉快なものではなかった」と書いている。

- ↑ 일본국헌법 제63조 에서는 총리는 의원으로부터 요구되면 국회에 참석해야 하는 규정이 존재한다.

- ↑ 질병 요양하고 있던 총리에게 의회 결의해까지 국회 출석을 요청하는 것은 하지 않았다.

- ↑ 총리로 맞이한 제26회 통상 국회의 시정 방침 연설 은 기시가 대독하고 있다.

- ^ (주)노벨상은 알프레드 노벨이 그 자산을 세계문명을 위해 상금으로 남겨놓음으로써 영원히 세계의 인심에 기념되었다. 세계의 인심을 새롭게 하고, 그 평화, 문명에 공헌하기 위해서, 「메이지 상금」이야말로 선제 폐하의 의지와 가장 합치한다.

- ↑ 『이시바시 하야마 전집』과 월보 의 발간 은 1970년 12월-1972년 9 월 [ 38 ] , ISBN 4492060103 , 4492060111 , 449206012X , 4492060148 , 4492060162 , 4492060170 , 4492060189 , ISBN 4492060200 , 4492060219 , 4492060227 , 4492060233 42

출처

[ 편집 ]- ^ 우에다 마사아키, 쓰다 히데오, 나가하라 케이지, 후지이 마츠이치, 후지와라 아키라 감수 저, 삼성당 편수소 편 「콘사이스 일본인 명사전」(제5판) 삼성당, 2009년 1월, 104페이지. ISBN 978-4-385-15801-3 .

- ^ a b 강 2014 , p. 1.

- ↑ a b c 마스다 1995 , pp. 3–4.

- ^ 마스다 1995 , p. 4.

- ^ a b c 강 2014 , p. 2.

- ^ a b 아사카와 2008 , p. 30.

- ↑ 아사카와 2008 , p. 194.

- ↑ 아사카와 2008 , pp. 30-31.

- ^ 아사카와 2008 , p. 15.

- ^ 아사카와 2008 , p. 17.

- ^ 아사카와 2008 , p. 18.

- ^ 아사카와 2008 , p. 19.

- ^ 마스다 1995 , p. 9.

- ^ a b c d 강 2014 , p. 31.

- ^ a b "육군 후비역 장교 동등 관복역 정년 연부. 다이쇼 15년 4월 1일조」

- ^ a b 강 2014 , p. 32.

- ^ a b 강 2014 , p. 29.

- ^ 아사카와 2008 , p. 79.

- ↑ 이사장 인사 사단 법인 경제 클럽

- ↑ 아사카와 2008 , pp. 79–80.

- ^ 마키노 & 코보리 2014 .

- ^ a b c d e f g h i 마츠오 1984 , pp. 310-313.

- ^ 이시바시 하야마 『이시바시 하야마 평론선집』 동양경제신보사, 1990년 6월, 391-392쪽. ISBN 4-492-06052-9 .

- ↑ 마키, 타무라 & 다나카 2012 , p. 78.

- ↑ 마키, 타무라 & 타나카 2012 , p. 79.

- ↑ “ 5-5 총선거 사료로 보는 일본의 근대 ”. 국립 국회 도서관 . 2020년 8월 14일 열람.

- ↑ 「과도경제력 집중 배제법 등을 폐지하는 법률(1970년 7월 25일 법률 제87호)」심의 경과 - 국립 국회 도서관 , 일본 법령 색인. 심의에서는 동법 폐지에 우려를 가진 일본 사회당 다나카 타케오 등으로부터의 질의를 받고 있다.

- ↑ 쇼와 32년 - 일본 의사회 ( PDF )

- ↑ “국민 모두 보험·여러분(12) 국민 모두 보험의 달성” . 요미우리 신문 . (2013년 8월 9일) 2016년 10월 25일 열람.

- ↑ 가사이 야스시 “고도 성장의 시대” 일본 평론사 , 1981년 4월, 114쪽. 전국 서지 번호 : 81022262 .

- ^ 지비 『총리대신 총 62명의 평가와 공적』 안트렉스 <서프라이즈 북>, 2020년 9월 8일, 93쪽. ASIN B08HMMVKYW .

- 스즈 무라 2023 , p. 207.

- ^ 핫토리 토시 라 “사전 유명인의 사망 진단” 근대편, 요시카와 히로후미칸, 2010년 4월 28일, 부록 “근대 유명인의 사인 일람” 3페이지. ISBN 978-4-642-08035-4 .

- ↑ 후나 바시 요이치『21세기 지정학 입문』 문예춘추 〈 분춘신서 1064〉, 2016년 2월, 249쪽. ISBN 978-4-16-661064-8 .

- ^ a b 다나카 히데토미 「경제 정책을 역사에 배운다」소프트뱅크 크리에이티브〈소프트뱅크 신서〉, 2006년 8월, 212-213쪽. ISBN 4-7973-3655-2 .

- ↑ “이시바시 히로야마 많이 말한다” “동양 경제 신보” 제2759호, 1957년 1월 5일, 26-29페이지.

- ↑ 동양 경제 쇼와 21년 3월 16일호 「사론」등

- ^ 이시바시 하야마, 이시바시 하야마 전집 편찬 위원회 “이시바시 하야마 전집” 동양 경제 신보사, 1970년. NCID BN02012516 . 총 15권

- ↑ “ 야마나시 평화 박물관 이시바시 히로야마 기념관 ”. www.museum-kai.net . 【참가관】 . 뮤지엄 카이 네트워크. 2025년 1월 10일 열람.

- ↑ “ 야마나시 평화 박물관~이시바시 히로야마 기념관~ ”. www.yamanashi-kankou.jp . 후지의 나라야마나시 관광넷.

- ↑ 이시바시 히로야마 전집 편찬 위원회 , pp. 287, 297.

- ↑ “부활 제1회 생존자 서훈 201명 발표” “요미우리 신문” 1964년 4월 28일 석간 1면

- ↑ “고이시바시 씨에게 키리하나 다이츠키” “요미우리 신문” 1974년 4월 26일 석간 2면

- ↑ 마스다 1995 , pp. 4-5.

- ^ 하세가와 외 2007 , p. 111.

- ↑ a b c 이시바시 히로야마 전집 편찬 위원회 2011 , p. 214.

- ↑ a b 이시바시 히로야마 전집 편찬위원회 2011 , p. 215.

- ↑ 이시바시 히로 야마 전집 편찬 위원회 2011 , p. 217.

- ^ a b c d e f 인사흥신소 편 『인사흥신록』 제15판, 인사흥신소, 1948년, 이52. NDLJP : 2997934/79 .

- ^ a b 다케우치 마사히로 『「가계도」와 「저택」에서 읽는 역대 총리 대신」ISBN 978-4-408-33718-0 .

- ^ 사토 아사야스『호벌 지방 호족의 네트워크』립풍 서방, 2001년 7월, 339쪽. ISBN 4-651-70079-9 .

- ↑ https://www.waseda.jp/top/news/67570

- ↑ https://www.ifsa.jp/index.php?Gishibashitanzan

참고문헌

[ 편집 ]- 아사카와 호『위대한 언론인 이시바시 히로야마』 야마나시 닛닛 신문사 〈 야마니 라이브러리〉, 2008년 4월. ISBN 978-4-89710-723-3 .

- 마키 히사코, 타무라 히데오, 다나카 히데토미 『일본 재건론 100조엔의 잉여 자금을 동원하라!』 후지와라 서점, 2012년 2월. ISBN 978-4-89434-843-1 .

- 이시바시 하야마 전집 편찬 위원회 편 「이시바시 하야마 연보」 「이시바시 하야마 전집」 제15권 보정판, 동양 경제 신보사, 2011년 7월. ISBN 978-4-492-06171-8 .

- 강극실 저, 일본 역사 학회 편 『이시바시 히로야마』 요시카와 히로후미칸 < 인물 총서 > , 2014년 2월. ISBN 9784642052719 .

- 일본경제신문사『 내 이력서』 제6집(이시바시 히토야마 외 ) , 일본경제신문사, 1958년, 37-96쪽. 전국 서지 번호 : 58011535 . 이후 개정판

- 문고 신판 하세가와 여시 한, 이시바시 히로야마, 오만 이득, 고바야시 용 「반골의 언론인」일본 경제 신문 출판사 <내 이력서>, 2007년 10월. ISBN 978-4-532-19419-2 .

- 마스다히로 『이시바시 히토야마 리베라리스트의 진수』중앙 공론 사〈중공 신서〉, 1995년 5월. ISBN 4-12-101243-7 .

- 마츠오 존토 편 ' 이시바시 히로야마 평론집' 이와나미 서점 < 이와나미 문고 >, 1984년 8월. ISBN 978-4-0033-1681-8 .

전기

[ 편집 ]- 코지마 직기 “기개인 이시바시 하야마” 동양 경제 신보사(신판), 2004년. 구판 「이단의 언설 이시바시 히토야마」 신시오샤 ( 상하), 1978

- 츠츠이 키요타다『이시바시 히로야마 이치자유주의 정치가의 궤적』 중앙공론사〈중공총서〉, 1986년

- 에미야 타카유키「정치적 양심에 따릅니다 이시바시 히로야마의 생애」

- 사다 카 노부「요시 일본주의 정치가 지금, 왜 이시바시 히토야마인가」 동양 경제 신보사, 1994년

- 신판 '히로야마 제명 소일본주의의 운명' 이와나미 현대 문고 , 2004년

- 반토 이치리『싸우는 이시바시 히로 야마 쇼와사에 이채를 발하는 굴복하지 않는 언론』 동양경제신보사, 2008년(신판). 그 밖에 중공 문고 , 1999년/ 치쿠마 문고 , 2019년

- 마스다 히로시 「이시바시 카츠야마 사상은 인간 활동의 근본·동력이 된다」미네르바 서방 < 일본 평전선 >, 2017년

- 호사카 마사야스「이시바시 히토야마의 65일」도요 경제 신보사, 2021년

- 스즈무라 유스케『정치가 이시바시 히로야마 견식 있는 「아마추어」의 신념』 중앙 공론 신사 <중공 선서>, 2023년 9월. ISBN 978-4-12-110141-9 .

- 마스다 히로시 『정치인·이시바시 히로야마 연구 리버럴 보수 정치가의 궤적』 동양 경제 신보사, 2023년

연구문헌

[ 편집 ]- 마스다 히로시 「이시바시 하야마 연구 「소일본주의자」의 국제 인식」 동양 경제 신보사, 1990 년

- 자매서 『이시바시 히로야마 점령 정책에 대한 저항』쿠사시샤 , 1988년, 온디맨드판 2003년

- 강극실 『이시바시 히로야마의 전후 인계받는 소일본주의』 동양경제신보사, 2003년

- 자매서 『이시바시 히로야마 자유주의의 척추』마루젠 라이브러리, 1994년

- 다나카 히데요시『일본 리버럴과 이시바시 히로야마 지금 정치가 필요하고 있는 것』 코단샤 선서 메치에, 2004년

- 나가유키 남자「이시바시 히로야마의 경제 사상 일본 경제 사상사 연구의 시야각」 동양 경제 신보사, 2009년

- 우에다 미와 「이시바시 히로야마론 언론과 행동」요시카와 히로후미칸, 2012년

- 마츠오 존토 '근대 일본과 이시바시 히로야마 '동양 경제 신보'의 사람들'동양 경제 신보사, 2013년

- 마키노 쿠니아키 , 코호리 사토시 "이시바시 히로야마와 "전시 경제 특별 조사실"-나고야 대학 소장 "아라키 미츠타로 문서"에서 "자유 사상" 제135호, 2014년, 38-54페이지, CRID 1522825130143327744 .

관련 항목

[ 편집 ]관련 인물

[ 편집 ]외부 링크

[ 편집 ]- 일반재단법인 이시바시 하야마 기념재단

- 이시바시 하야마상 ( 동양경제 WebSite 내) - 2008년 12월 2일 시점의 아카이브

- 이시바시 하야마 연재 일람 | 연재/이시바시 하야마를 말한다 - 동양 경제 신보사 115주년 - 웨이백 머신 (2016년 8월 18일 아카이브분)

- 입정대학

- 이시바시 하야마 관련 문서 | 국립 국회 도서관 헌정 자료실

- 와세다 사람 이름 데이터베이스 이시바시 하야마

- 와세다 대학 표창 데이터베이스 | 명예 박사

- 이시바시 하야마 - NHK 인물록

- 『 이시바시 하야마』 - 코트뱅크

- 「이시바시 히토야마」의 조사방법 (立正大学古書資料館) - 레퍼런스협동 데이터베이스

Tanzan Ishibashi

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2016) |

Tanzan Ishibashi | |

|---|---|

石橋 湛山 | |

Official portrait, 1956 | |

| Prime Minister of Japan | |

| In office 23 December 1956 – 25 February 1957 | |

| Monarch | Hirohito |

| Preceded by | Ichirō Hatoyama |

| Succeeded by | Nobusuke Kishi |

| President of the Liberal Democratic Party | |

| In office 14 December 1956 – 21 March 1957 | |

| Vice President | Banboku Ōno |

| Secretary-General | Takeo Miki |

| Preceded by | Ichirō Hatoyama |

| Succeeded by | Nobusuke Kishi |

| Director-General of the Japan Defense Agency | |

| In office 23 December 1956 – 31 January 1957 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Funada Naka |

| Succeeded by | Nobusuke Kishi |

| Minister of Posts and Telecommunications | |

| In office 23 December 1956 – 27 December 1956 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Isamu Murakami |

| Succeeded by | Taro Hirai |

| Minister of International Trade and Industry | |

| In office 10 December 1954 – 23 December 1956 | |

| Prime Minister | Ichirō Hatoyama |

| Preceded by | Kiichi Aichi |

| Succeeded by | Mikio Mizuta |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 22 May 1946 – 24 May 1947 | |

| Prime Minister | Shigeru Yoshida |

| Preceded by | Keizo Shibusawa |

| Succeeded by | Tetsu Katayama (Acting) |

| Member of the House of Representatives for Shizuoka 2nd District | |

| In office 1 October 1952 – 29 January 1967 | |

| In office 26 April 1947 – 17 May 1947 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Seizō Sugita 25 September 1884 Tokyo, Japan |

| Died | 25 April 1973 (aged 88) Osaka, Japan |

| Political party | Liberal Democratic Party (1955–1973) |

| Alma mater | Waseda University |

| Signature |  |

Tanzan Ishibashi (石橋 湛山, Ishibashi Tanzan, 25 September 1884 – 25 April 1973) was a Japanese journalist and politician who served as prime minister of Japan from 1956 to 1957.

Born in Tokyo, Ishibashi became a journalist after graduating from Waseda University in 1907. In 1911, he joined the Tōyō Keizai Shimpo ("Eastern Economic Journal") and served as its editor-in-chief from 1925 to 1946 and president from 1941. In the 1930s, Ishibashi was one of the few critics of Japanese imperialism, and became well-known as a liberal economist. From 1946 to 1947, Ishibashi served as finance minister under Shigeru Yoshida. He was elected into the National Diet in 1947, but was purged for openly opposing the U.S. occupation policies; he returned to the Diet in 1952, after which he allied with Ichiro Hatoyama and served as his minister of international trade and industry. Ishibashi succeeded Hatoyama as prime minister in 1956, simultaneously serving as director of the Defense Agency, but resigned soon after due to ill health.

Life

[edit]Ishibashi was born in the Shibanihonenoki district of Azabu ward, Tokyo in 1884, the eldest son of Sugita Tansei (1856–1931),[1] a Nichiren Buddhist priest and the 81st head of Kuon-ji temple in Yamanashi prefecture. Ishibashi, who took on his mother's surname, would later become a Nichiren priest himself.[2][3] As a member of the Nichiren-shū sect of Nichiren Buddhism, Tanzan was his Buddhist name; his birth name was Seizō (省三). He studied philosophy and graduated from Waseda University's literature department in 1907.[4]

He worked as a journalist at the Mainichi Shimbun for a while. After he finished military service, he joined the staff of the Tōyō Keizai Shimpo ("Eastern Economic Journal"), later becoming its editor-in-chief and finally company president in 1941. For the Tōyō Keizai, Ishibashi wrote about Japanese financial policy, developing over time a new liberal perspective.[5]

Ishibashi had a liberal political view and was one of the most consistent proponents of individualism during the Taishō Democracy movement. In this regard, he also promoted a feminist perspective, advocating comprehensive "legal, political, educational, and economic" equality for women so that they could better thrive in the competitive modern society, in contrast to the stratified conditions of feudal life.[6] Ishibashi was also one of the rare personalities who opposed Japanese imperialism.[7] Instead, he advocated a "Small Japan" policy (小日本主義, shō-Nihon-shugi), which advocated the abandonment of Manchuria and Japanese colonies to refocus efforts on Japan's own economic and cultural development.[5][8] In addition, he allied himself with Tanaka Ōdō in arguing for free trade and international cooperation over militarism and colonialism.[6]

After World War II Ishibashi received an offer from the Japan Socialist Party to run for the National Diet as their candidate. However, Ishibashi declined, and instead accepted a post of "advisor" to the newly formed Liberal Party.[9] Ishibashi then served as Minister of Finance in Shigeru Yoshida's first cabinet from 1946 to 1947. Ishibashi was elected to the Diet for the first time in the April 1947 general election, representing Shizuoka's second district, but less than one month later he was purged and forced to resign for having openly opposed U.S. Occupation policies.[10] Following his de-purging in 1951, Ishibashi allied with Ichirō Hatoyama and joined the movement against Yoshida's cabinet. In 1953, Hatoyama became prime minister, and Ishibashi was appointed Minister of Industry. Around this time, Ishibashi became known as a supporter of revising Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution and remilitarizing Japan.[11] In 1955, the new Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) was established as a combination of smaller conservative parties, with Ishibashi as a founding member.

When Hatoyama retired in 1956, the LDP held a vote for their new president. At first Nobusuke Kishi was considered the most likely candidate, but Ishibashi allied himself with another candidate, Mitsujirō Ishii, and won the election, becoming the new Prime Minister of Japan.[12] In the postwar period, a practice had developed whereby each prime minister would attempt to achieve a major foreign policy objective.[13] Shigeru Yoshida had secured the peace treaty which ended the Occupation, Hatoyama had negotiated the resumption of diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, and now Ishibashi stated that his main objective would be resuming diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China.[14] Ishibashi also signaled that he would endeavor to take a cooperative approach to the political opposition, resulting in high public approval ratings.[15] He became sick and resigned two months later, with Kishi taking over as prime minister.[16]

Even after Ishibashi resigned the posts of prime minister and president of LDP, he remained a powerful faction boss and prominent figure among ex-Liberal Party politicians in the LDP. Ishibashi opposed Kishi's efforts to force through a revised version of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty in 1960, which he felt were too extreme. When Kishi had opposition lawmakers physically removed from the Diet by police and rammed the new treaty through on May 19, 1960, Ishibashi was one of several LDP faction bosses who boycotted the vote in protest.[17]

Ishibashi also remained a major figure in Japan's ongoing efforts to engage with the People's Republic of China,[4] making a personal visit to China in 1963.[18] From 1952 to 1968 he was also the president of Rissho University. Tanzan Ishibashi died on April 24, 1973.[19]

Waseda University later introduced the Waseda Journalism Award In Memory of Ishibashi Tanzan in 2001.[20]

Political philosophy, ideology and views

[edit]Ishibashi's views were based on new liberalism, individualism and feminism.[21][22] Ishibashi was opposed to Japanese imperialism, colonialism and militarism.[23][24] Because of his anti-imperalist views he advocated for a Small Japan" policy (小日本主義, shō-Nihon-shugi), which advocated the abandonment of Manchuria and Japanese colonies to refocus efforts on Japan's own economic and cultural development.[25][26] In addition to that, he allied with Tanaka Ōdō to support free trade and international cooperation.[27]

Honors

[edit]From the corresponding article in the Japanese Wikipedia

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (29 April 1964)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers (25 April 1973; posthumous)

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Sugita Nippu". Wikidata.

- ^ "石橋湛山は得度しているが、僧籍はあるか.あるとしたら日蓮宗の僧階は何か". Collaborative Reference Database (in Japanese). National Diet Library. November 2, 2019.

- ^ Murphy, Trevor (2004). "The Leprosy Relief Work of Tsunawaki Ryūmyō". The Eastern Buddhist. 36 (1/2): 8. JSTOR 44362378.

- ^ a b "Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures — Ishibashi Tanzan". National Diet Library. 2013.

- ^ a b Keshi, Jiang (c. 2006). "Ishibashi Tanzan's World Economic Theory: The War Resistance of an Economist in the 1930's" (PDF). Princeton University.

- ^ a b Nolte, Sharon Hamilton (August 1984). "Individualism in Taishō Japan". The Journal of Asian Studies. 43 (4): 667–684. doi:10.2307/2057149. JSTOR 2057149. S2CID 162629157.

- ^ Inoki 2016, pp. 89–90.

- ^ "The wisdom of Tanzan Ishibashi". 20 October 2017.

- ^ Inoki 2016, p. 90.

- ^ Inoki 2016, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Hajimu, Masuda (July 2012). "Fear of World War III: Social Politics of Japan's Rearmament and Peace Movements, 1950—3". Journal of Contemporary History. 47 (3): 558. doi:10.1177/0022009412441650. JSTOR 23249006. S2CID 154135817.

- ^ Inoki 2016, p. 87.

- ^ Kapur 2018, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 80.

- ^ "Period of President Ishibashi's Leadership". Liberal Democratic Party.

- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 12.

- ^ Kapur 2018, p. 89.

- ^ "Chairman Mao Meets with Former Japanese PM". China-Japan Year of Cultural & Sports Exchanges: Historical Gallery. China Internet Information Center. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ "Tanzan Ishibashi Dies at 88; Was Former Premier of Japan". The New York Times. 25 April 1973.

- ^ In Pursuit of Excellent Journalism -The Course of the Waseda Journalism Award

- ^ http://www.princeton.edu/~collcutt/doc/Keshi_English.pdf

- ^ https://www.jstor.org/stable/2057149

- ^ https://books.google.de/books?id=rG7TCwAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y

- ^ https://www.jstor.org/stable/2057149

- ^ http://www.princeton.edu/~collcutt/doc/Keshi_English.pdf

- ^ https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2017/10/20/commentary/japan-commentary/wisdom-tanzan-ishibashi/#.XD3mVPZFw5s

- ^ https://www.jstor.org/stable/2057149

Sources cited

[edit]- Inoki, Takenori (2016). "Ishibashi Tanzan: A Coherent Liberal Thinker". In Watanabe, Akio (ed.). The Prime Ministers of Postwar Japan, 1945-1995. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. pp. 87–97. ISBN 978-1-4985-1001-1.

- Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674984424.

Further reading

[edit]- Liberalism in Modern Japan: Ishibashi Tanzan and His Teachers, 1905-1960, by Sharon H. Nolte, Published by University of California Press, 1986

- Ishibashi Tanzan's World Economic Theory - The War Resistance of an Economist in the 1930s, Princeton University (http://www.princeton.edu/~collcutt/doc/Keshi_English.pdf)

[신상목의 스시 한 조각] [34] 일본 총리의 3·1절 축전을 꿈꾸며

신상목 기리야마본진 대표·前 주일대사관 1등 서기관

입력 2019.02.22. 03:11

1

칼럼 관련 일러스트

전후(戰後) 일본 총리를 역임한 언론인 이시바시 단잔(石橋湛山)은 1919년 5월 15일 자 동양경제신보에 다음과 같은 사설을 싣는다. “어느 민족인들 타민족에게 복속되는 것을 유쾌하게 받아들일 리 없다. 조선 민족은 고유한 언어와 오랜 독립의 역사를 갖고 있다. 그들은 독립을 회복할 때까지 일본 통치에 계속 저항할 것이며 지식과 자각의 증진에 비례하여 저항은 더욱 거세질 것이다.”

5월 20일 자 요미우리신문에는 민예운동가 야나기 무네요시(柳宗悅)가 기고문을 남긴다. "물질도 영혼도 그들의 자유, 독립을 강탈하였다. 조선인들이여, 일본인들이 그대들을 모욕하고 고통스럽게 하여도 그들 가운데 이와 같은 일문(一文)을 남긴 자가 있음을 알아주오. 일본이 정의로운 인도(人道)의 길을 걷고 있지 못함에 대한 명백한 반성이 우리 일본인 사이에도 있음을 알아주오."

단잔은 1922년 '대일본주의의 환상' 사설에서 식민지 포기, 일·중 관계 개선, 개방적 무역이 일본의 살길이라는 '소일본주의'를 제창한다. 당시 일본 내부에서도 일본이 잘못된 길을 걷고 있음을 통절히 비판하는 목소리가 있었다. 3·1운동은 그들의 인식에 큰 영향을 미쳤고 그 후 역사는 그들이 옳았음을 증명했다.

3·1운동이 제시한 민족 자결, 비폭력 사상은 지나간 역사가 아니다. 그것은 전후 일본이 추구해 온 반전(反戰)·평화 염원과 일치하는 현재진행형의 보편적 이념이다. 일본은 한국만큼이나 3·1운동의 의미를 되새겨야 하는 나라다. 3·1운동은 일본의 역사이기도 하다.

나는 언젠가 일본 총리가 3·1절 축전을 보내오는 날을 꿈꾼다. 일본 국민을 대표해 일본 정상이 한국 정상에게 전하는 3·1절 축전만큼 ‘과거를 직시(直視)한다’는 수사(修辭)에 구체성을 부여하고 진정성을 입증하는 것도 없을 것이다. 과거 앞에 겸허해지는 것은 용기가 필요한 일이다. 독일 총리는 유럽 화합을 위해 연합국 전승기념식에도 참가하는 용기를 낸다. 동아시아 화합을 위한 일본의 용기를 기대하고 싶다.

===

Japanese Liberalist's View on National Identity and Strategy in the Early 20th Century: The case of Ishibashi Tanzan(石橋湛山)

AskAI

戰前 일본 자유주의자의 국가구상과 동아시아 : 石橋湛山의 小日本主義를 중심으로

논문 기본 정보TypeAcademic journalAuthor

Young-June ParkJournalThe Korean Political Science AssociationKorean Political Science ReviewVol.39 No.2KCI Excellent Accredited JournalPublished2005.6Pages27 - 43 (19page)

Usage468

CiteView PDFAI Summary

📌Topic이 연구는 일본의 자유주의자인 이시바시 탄잔이 제안한 소일본주의와 그에 따른 일본의 국가 정체성 및 동아시아에 대한 전략을 분석한다.

📖Background일본은 청일전쟁과 러일전쟁에서 승리하며 국제 정치의 중심으로 부상하였고, 이에 따라 일본 내에서 새로운 국가 정체성과 전략의 모색이 필요하게 되었다.

🔬Method이 연구는 이시바시 탄잔의 논설을 분석하여 그의 정치적 사상과 국가 전략을 재구성하며, 이를 통해 그가 제시한 소일본주의의 현대적 의의를 탐구한다.

🏆Result이시바시 탄잔은 일본이 관세 자주권 회복 이후, 대일본주의의 팽창적 정책에 반대하며 국내적으로 민주주의의 완성과 동아시아식민지의 자치 및 독립을 주장하였다.

AI Summary

Abstract· KeywordsReport Errors

After the victory in the Russo-Japanese War and the First World War, Japan had emerged as a great power in the international arena from the previous status as a peripheral state. In coincidence with the rising of its international status, Japanese strategists groped for a new national strategy. Most of them, including the Imperial Army's strategists, suggested a strategy of expansion which asserted the enlargement of an offensive posture towards the continent. On the contrary, Ishibashi Tanzan, who started his career as a novice journalist at that time, raised a critical view against the so-called Great Japanism(大日本主義).

This paper tries to analyzize Ishibashi Tanzan's view on Japan's national identity and strategy toward East Asia through the content analysis of his articles. Based on the philosophical background of Liberalism and traditional Budhisim, Tanzan suggested a three-dimensiona strategy for Japan. According to him, domestically, Japan should pursue the completion of democracy. Regionally, Japan had to desert the obtained right of colonial rule. And internationally, Japan must participate in the internatioal move toward military reduction after World War I. It seems that Tanzan's political thought contains the elements of Immanuel Kant's phiolosophy of peace in that it suggested a three-dimensional solution for Japan and Asia's peaceful change. For the modern Japanese strategists who are searching for Japan's new role in the 21st century Tanzan's view on national identity would be a good criterion to be consider.View more

#이시바시 탄잔(石橋湛山)#대일본주의#소일본주의#국가정체성#일본형 자유주의#Ishibashi Tanzan#Japanese Liberalism#Great Japanism#National Identity#Little Japanism

AI Summary

Topic

이 연구는 일본의 자유주의자인 이시바시 탄잔이 제안한 소일본주의와 그에 따른 일본의 국가 정체성 및 동아시아에 대한 전략을 분석한다.

Background

일본은 청일전쟁과 러일전쟁에서 승리하며 국제 정치의 중심으로 부상하였고, 이에 따라 일본 내에서 새로운 국가 정체성과 전략의 모색이 필요하게 되었다.

Method

이 연구는 이시바시 탄잔의 논설을 분석하여 그의 정치적 사상과 국가 전략을 재구성하며, 이를 통해 그가 제시한 소일본주의의 현대적 의의를 탐구한다.

Result

이시바시 탄잔은 일본이 관세 자주권 회복 이후, 대일본주의의 팽창적 정책에 반대하며 국내적으로 민주주의의 완성과 동아시아식민지의 자치 및 독립을 주장하였다.

주요내용

이시바시 탄잔은 일본의 대일본주의를 비판하며, 민주적 체제를 완성하고 동아시아의 자치와 독립을 주장했으며, 일본이 국제사회에서 군비 축소와 협조 외교의 방향으로 나아가야 한다고 강조하였다.ViewAI Summaryby TOC

Contents

논문요약

Ⅰ. 머리말

Ⅱ. 일본의 지위변화와 역할모색

Ⅲ. 소일본주의의 국내적 과제: 데모크라시의 완성

Ⅳ. 소일본주의와 동아시아 질서: 식민지의 자치ㆍ독립론

Ⅴ. 소일본주의와 국제질서: 군비축소ㆍ협조외교ㆍ통상자유

Ⅵ. 맺는 말

참고문헌

영어 초록

References(26)Add References

박영준. 2004. "러일전쟁 직후 일본 해군의 국가구상과 군사전략론: 사토 테츠타로 『帝國國防史論』(1908)을 중심으로."『한국정치외교사논총』 제26집 1호.

박영준. 2003. "21세기 일본의 국가구상 논쟁과 그 정책적 전망: 사카모토 다카오와 강상중의 논쟁을 중심으로." 『국가전략』 제9권 1호.

박영준. 2003. "21세기 일본의 국가구상 논쟁과 그 정책적 전망: 사카모토 다카오와 강상중의 논쟁을 중심으로." 『국가전략』 제9권 1호.  박영준. 1993. "칸트의 평화사상 연구." 『육사논문집』 제44집.

박영준. 1993. "칸트의 평화사상 연구." 『육사논문집』 제44집.  한상일. 2000. "요시노 사쿠조와 식민자치관의 원형." 『일본 지식인과 한국』. 서울: 오름.

한상일. 2000. "요시노 사쿠조와 식민자치관의 원형." 『일본 지식인과 한국』. 서울: 오름.  한상일. 2004. 『제국의 시선: 일본의 자유주의 지식인 요시노 사쿠조와 조선문제』. 서울: 새물결.

한상일. 2004. 『제국의 시선: 일본의 자유주의 지식인 요시노 사쿠조와 조선문제』. 서울: 새물결.

No comments:

Post a Comment