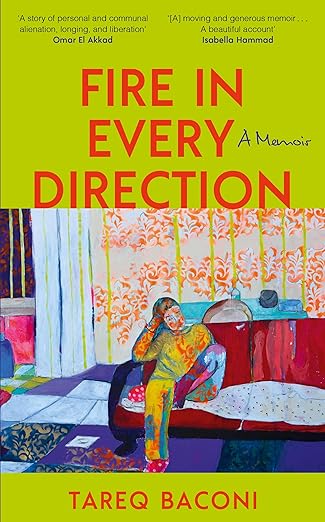

Kindle$16.99

Audiobook

Paperback$26.25

Follow the author

Tareq BaconiTareq Baconi

by Tareq Baconi (Author) Format: Kindle Edition

'Moving and generous'

Isabella Hammad, author of Enter Ghost

'Luminous, moving, and achingly beautiful'

Maaza Mengiste, author of The Shadow King

'I am forever changed after reading this book'

Javier Zamora, author of Solito

'A deeply inspiring and absorbing read'

Mark Gevisser, author of The Pink Line

'Spending time with the real people in Fire in Every Direction is a delight'

Rabih Alameddine, author of An Unnecessary Woman

Both a love story and a coming-of-age tale that spans countries and continents, Fire in Every Direction balances humour and loss, nostalgia and hope, as it takes us from the Middle East to London, and from 1948 to the present. Tareq Baconi crafts a deeply intimate, unforgettable portrait of how a political consciousness - desire and resistance - is passed down through generations.

In 1948, Tareq's grandmother would flee Haifa as Zionist militias seized the city. In the late 1970s, she would flee Beirut with her daughter, as the country was in the throes of a civil war. In Amman, the family would eventually obtain the comfort of middle-class life - still, a young Tareq would feel trapped: by cultures of silence, by a sense of not belonging, by his own growing awareness that he is in love with his childhood best friend, Ramzi.

After relocating to London, Tareq hopes to put aside his past. Yet as the Iraq War radicalizes young people around the world towards anti-war protest, history comes back to him.

Living between the region and London, Tareq fits in neither and feels alienated from both. Queerness is policed back in Amman, just as his Palestinian-ness is abroad. These gradual estrangements escalate, forcing him to grapple with what it means to live in liminal spaces, and rethink the meaning of home.

Print length 256 pages

Product description

Review

Tareq Baconi refuses to separate the story of sexual identity from the story of political commitment, and in so doing models a way to see our personal struggles as intertwined with our collective ones. Fire in Every Direction is a beautiful account of one man's confrontation with the histories, silences, and desires - both communal and private - that have made him who he is.

In stunning detail - both physical and emotional - Baconi traces a story of personal and communal alienation, longing, and liberation. Drawn here in beautiful, crushing clarity is an account of what systems of degradation, fear and theft can do to a person, a society, a world. That Baconi has managed to do all this in a memoir that still feels so firmly rooted in love is a marvel.

In a time when it can feel like language has been stripped of meaning and words have lost all power, Fire in Every Direction arrives as an affirmation and a refusal of silence . . . You do not read this book to repair your heart, you read this book to understand the fissures

In Fire in Every Direction, we not only see how the oppression of a people has affected one Palestinian family, but how oppression in all forms - colonialism, patriarchy, homophobia, to name a few - creates dishonesty and masks within all of us. Tareq Baconi offers us a love letter, a blueprint on how to craft a life that questions the present, dreaming a better future in the process

A powerful memoir of queer and Palestinian reckoning. Tareq Baconi creates "a gaze of our own" by bringing his open heart to a tough confrontation with histories both intimate and diasporic. An important contribution to our many literatures.

With passion, sincerity, and wit, Baconi writes about the world he grew up in, about a time and place long gone, revivified in these beautiful pages. Spending time with the real people in Fire in Every Direction is a delight. Read this book!

With eloquence, passion, and insight, Tareq Baconi weaves his personal story as a queer kid growing up in the refugee community in Jordan, into the larger narrative of his family's dislocation, and the Palestinian struggle. In so doing, he gives new meaning to the concept of liberation, personal and political.

About the Author

Tareq Baconi is a Palestinian writer, scholar, and activist. He is the grandson of refugees from Jerusalem and Haifa and grew up between Amman and Beirut. His work has appeared in, among others, The New York Times and The Baffler, and he contributes essays to The New York Review of Books and the London Review of Books. He has also written for film; his award-winning BFI short One Like Him, a queer love story set in Jordan, screened in over thirty festivals. He is the author of Hamas Contained: A History of Palestinian Resistance, which was shortlisted for the Palestine Book Award, and Fire in Every Direction. --This text refers to an alternate kindle_edition edition.

Book Description

From the renowned Palestinian scholar, a memoir of political and queer awakening, of impossible love amidst generations of displacement, and what it means to return home. --This text refers to an alternate kindle_edition edition.

Fire in Every Direction: A Memoir

Fire in Every Direction: A MemoirPublication date : 12 February 2026

Language : English

Print length : 256 pages

===

https://www.npr.org/2025/11/04/nx-s1-5558324/tareq-baconi-talks-about-his-new-memoir-fire-in-every-direction

Author Interviews

Tareq Baconi talks about his new memoir 'Fire in Every Direction'

November 4, 20254:41 AM ET

Heard on Morning Edition

Leila Fadel

7-Minute Listen

Transcript

NPR's Leila Fadel speaks to Tareq Baconi, a Palestinian scholar. His memoir, "Fire in Every Direction," explores queer identity, family history, and political awakening.

LEILA FADEL, HOST:

A grandmother flees Palestine as a child on a fisherman's boat. A family is uprooted from Lebanon after a massacre of refugees. A writer grows up with a culture of silence in Jordan. Tareq Baconi, a renowned Palestinian scholar, has written a memoir of three generations of displacement. It's called "Fire In Every Direction," and Tareq Baconi is with me now. Thank you for being here.

TAREQ BACONI: Thank you for having me.

FADEL: So in your book, you start with unpacking a yellow box full of letters from a childhood friend named Ramzi. Who was he to you?

BACONI: Well, Ramzi was the first boy that I fell in love with, and we were each other's - in some ways, I mean, it's funny to say that because we were neighbors but also pen pals because we used to write each other letters the whole time that we knew each other.

FADEL: Central to this book is growing up in Amman, Jordan, you really keep part of who you are and yourself a secret, almost even from yourself. And you start to fall in love with this boy, Ramzi. And you describe it as wearing a mask. What happens when you start to peek out from behind the mask and confess your feelings?

BACONI: Well, I mean, the mask was also something that protected me in the sense that I was afraid of what it would mean to acknowledge these feelings, and the mask would help me pretend that everything was as it should be. And that was sort of increasingly unsustainable until I teased the mask off a bit and tried to write to him about my feelings, and the reaction was swift and brutal, and that was the last time we spoke.

FADEL: Throughout the book, you use this Arabic word ayb - shame - you know, which I'm very familiar with too. Arab American woman growing up and you just like, oh, I - this is ayb. You can't do this. You can't be like this. And that was sort of the start of your mother's life with your father, right? Like, oh, you can't just be dating now that you're in Jordan. We don't do this. You have to get married. And I just wonder, like, that theme, how it shaped the narrative.

BACONI: Well, I mean, the notion of ayb - of shame - I think is very oppressive and it's very resilient wherever you are, whether you're growing up in an Arab family in the U.S. in the West or back home. I think the strictures of ayb are very confining. But I think that notion of shame I was really attracted to it or interested in it because I just - it's completely shaped my life - my experience as a queer boy growing up, my mom's experience as a political feminist who's working to organize and to be a committed activist. The same notions of ayb shape us.

FADEL: So in college in London in 2003, you're going through this political awakening, but you've also been going through this very personal awakening for yourself. And there's a point where you tell your mother, you know, I'm a gay man, and she listens and she hears you. And she says, OK, we got to tell your dad.

(LAUGHTER)

FADEL: And you go back and tell your dad. What was that conversation like?

BACONI: It was very difficult. I knew that that was the beginning of a journey for them and a continuation of one for me. And so I was prepared to not see him for a long time after that. I approached it with a lot of trepidation, and actually, my mom did as well because she put sedatives in his coffee to make sure.

(LAUGHTER)

FADEL: Just drug him a little for this one.

BACONI: (Laughter) Just drug him a little, which, you know, in hindsight, Arab mama in an Arab home, she knows what she's doing.

(LAUGHTER)

FADEL: Oh, man.

(LAUGHTER)

FADEL: When you tell your dad, he says - and you said damaging things, and I'm sure this was hurtful to hear. He says you cannot live in Jordan anymore, that this is no longer the place for you. When you go to Haifa and find your grandmother's childhood home that she was displaced from in 1948, you cannot bring yourself to ring the doorbell. It seemed like you were searching for home. Have you found that?

BACONI: Yes. I have. I have found that. My concept of home now is in my chosen family. And then home has come to mean something else to me. It's not this sense of needing to go back to somewhere. I think it's - my concept of it has evolved.

FADEL: It was very heartwarming to read near the end of the book where your dad just, like, loves your husband. He's like, when are you coming back to Beirut? It's just a totally - like, it - things changed, like, once you were open and clear to them about who you were and that you wouldn't back down from who that was.

BACONI: Absolutely. I think that he surprised me in so many ways. My dad has passed now but, you know...

FADEL: I'm so sorry.

BACONI: ...Before he passed away, I just couldn't believe where he got to and how he embraced me. And it really affirmed my impulse that, you know, these silences, who are they serving? My relationship with my father is much, much - or was much more loving and more honest than it ever was when I was hiding parts of myself from him.

FADEL: Yeah. Your first book is a very well-known book called "Hamas Contained" - a totally different book than the one I read. What was it like writing such a personal work that speaks to this larger question around displacement and loss and war and belonging?

BACONI: It was challenging in ways that I hadn't necessarily anticipated. You know, writing analytically or writing academically is important, but it's also a way of hiding - at least it was for me.

FADEL: Yeah.

BACONI: And this book was a way of going into the lived experience. What does it mean that I'm the grandson of four refugees from Palestine, now having to witness a Nakba and being - or a genocide, the continuation of the Nakba - and being unable to stop it. And in that way, I found it painful but also cathartic and important for me on a personal level. You know, the funny thing is, I'm a very private person and I - you know, I would've never imagined writing a memoir. But actually, writing this book was the only way I could really confront myself and sit with myself and sort of embrace who I'd become as a person in all of its different facets.

FADEL: Is it freeing to have it in the world?

BACONI: Well, we'll find out. It's...

(LAUGHTER)

BACONI: You know, I keep saying this is either the bravest or the stupidest thing I've done, and we'll find out soon enough.

FADEL: Tareq Baconi is the author of "Fire In Every Direction." Thank you, Tareq.

BACONI: Thank you for having me.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Copyright © 2025 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

Accuracy and availability of NPR transcripts may vary. Transcript text may be revised to correct errors or match updates to audio. Audio on npr.org may be edited after its original broadcast or publication. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

===

===

https://www.democracynow.org/2025/11/6/tareq_baconi

“Fire in Every Direction”: Palestinian Author Tareq Baconi on Gaza, Zionism & Embracing Queerness

StoryNovember 06, 2025

TopicsPalestine

Author Interviews

LGBTQ

Books

GuestsTareq Baconi

Palestinian analyst and writer.

Links"Fire in Every Direction"

"Hamas Contained: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance"

This is viewer supported news. Please do your part today.Donate

Palestinian writer Tareq Baconi joins us to discuss his new memoir, Fire in Every Direction, a chronicle of his political and queer coming of age growing up between Amman and Beirut as the grandson of refugees from Jerusalem and Haifa. While “LGBTQ+ labels have also been used by the West as part of empire,” with colonial projects seeking to portray Native populations as backward and in need of saving, “there’s a beautiful effort and movement among queer communities in the region to reclaim that language,” says Baconi. “I identify as a queer man today as part of a political project. It’s not just a sexual identity. It expands beyond that and rejects Zionism and rejects authoritarianism, and that’s part of my queerness.”

Baconi also comments on the so-called ceasefire agreement in Gaza and the election of Zohran Mamdani in New York City. “Palestinians are the ones that have to govern Palestinian territory, not this international force that comes in that takes any kind of sovereignty or agency away from the Palestinians,” he says.

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: We turn now to Gaza, where Israel’s military has killed at least two Palestinians in separate attacks. Israel claimed the men had approached the so-called yellow line that leaves more than half of the Gaza Strip under Israeli occupation. Israel has now killed at least 241 Palestinians since the U.S.-brokered ceasefire took effect on October 10th.

This comes as the Norwegian Refugee Council reports Israel is allowing just a hundred aid trucks a day to enter Gaza, far short of the 600 trucks per day Israel had pledged under the ceasefire deal.

This is Umm Amir Muqat, a displaced Palestinian in Gaza City.

UMM AMIR MUQAT: [translated] We have no life here. We’ve lost all hope. We returned to a pile of rubble. We have no water. We have no food. We came back to rubble. We hoped our house would still be there, but there’s no suitable place for us to live. We need a tent to live in, for us and for our children, and to have our lives back to the way it was before.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re joined now by the Palestinian analyst and writer Tareq Baconi. He’s author of a new memoir, Fire in Every Direction. He’s the grandson of refugees from Jerusalem and Haifa, grew up between Amman, Jordan, and Beirut, Lebanon. He’s the president of the board of Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network. He’s also author of Hamas Contained: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance. His award-winning short film is titled One Like Him. It is a queer love story set in Jordan. He’s a former senior analyst for the International Crisis Group on Israel-Palestine.

Welcome back to Democracy Now!

TAREQ BACONI: Thanks for having me.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s great to have you with us. Congratulations —

TAREQ BACONI: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: — on the publication of your book, Fire in Every Direction. Before we get to that, though, the latest. You are also an expert on Hamas, looking at, I mean, not even one-sixth of the aid is getting through that was promised by Israel since the ceasefire, and the killings continue, both in Gaza and the occupied West Bank.

TAREQ BACONI: Listen, historically, every ceasefire that was negotiated between Hamas and Israel had adopted a phased approach. There would be the first phase, where there would be the ostensible cessation of hostilities. And then, after that, the idea was always that the negotiators would propel the parties to move into reconstruction, to move into lifting the blockade, to move into other aspects that would make life in Gaza livable. And the reality is that, historically, every ceasefire got stuck in the first phase. There was never a real push to get Israel to adopt or to respect the second and third phases of the ceasefire. The parties would get stuck in the first phase.

And so, when this was negotiated, that was, I think, on the Palestinian side, always the fear, that Hamas would release the captives, it would release the bodies of the captives, and then nothing would happen in terms of forcing Israel to respect the commitments that it had made under the ceasefire. And lo and behold, this is exactly where we’re at. When the ceasefire, or the so-called ceasefire, was negotiated, the idea was that the U.S. would act as a guarantor and that it would compel Israel to abide by its commitments. The reality is that the killing hasn’t stopped. This is not a ceasefire. The killing hasn’t stopped. The starvation continues. The aid that’s going in is nowhere near what is needed. There’s no ability to allow Palestinians to go back to any semblance of a dignified life. And so, the reality is that the narrative is of a ceasefire; the reality is of the continuation of the genocide.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And what do you think? I mean, even if they were to move on to the second phase of the ceasefire deal, I mean, your assessment of the deal overall?

TAREQ BACONI: Listen, the assessment of the deal overall is that it’s a horrific — it’s a horrific deal. It doesn’t give the Palestinians any space for actual self-governance. It also gets to — it brings Israel off the hook entirely. The Israeli regime has committed a genocide for two years, live-streamed for everyone to see. And the narrative of the ceasefire is that now we just go back into this language of reconstruction and peace. Where is accountability? Netanyahu is a wanted war criminal. The people around him are war criminals. How do we deal with the fact that this live-streamed genocide is now being normalized, and we just are expected to go back into a reality where we talk about peace and reconstruction? Before we do any of that, there has to be accountability. And Palestinians are the ones that have to govern Palestinian territory, not this international force that comes in, that takes any kind of sovereignty or agency away from the Palestinian people.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And you’ve also, of course, written a book, as we mentioned, on Hamas. What about the requirement, the provision, of Hamas having to disarm and relinquish political power in Gaza?

TAREQ BACONI: Hamas has always been consistent that it would be part of a Palestinian polity that would be inclusive, that brings other Palestinian factions in, that collectively are able to determine what future Palestinians might have. The requirement for disarmament has always been a tool that Israel has used and the U.S. has used to justify continued acts of oppression and violence against the Palestinian people. I’ve always said the same thing. If Hamas were to disappear tomorrow, if all of its weapons were to disappear tomorrow, the blockade will not end. The genocide will not end. This is not about Hamas. This is an Israeli war against the Palestinian people. It’s a demographic war aimed at exterminating as many Palestinians as possible.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And finally, before we go to your book, of course, you’ve been in New York the last few days, and you’ve witnessed the victory of Zohran Mamdani. So, if you could — a couple of things — first, say, you know, what you think that indicates in terms of a possible change in the U.S. — I mean, not that New York City is necessarily representative — but a change in the position among people on Israel-Palestine, and also the response of his — in Israel-Palestine to his victory?

TAREQ BACONI: Listen, I think it’s an incredible — it’s an incredible moment, and I think it really shows the potential for real politics that is representing what people — what people, the general population, feels around these key issues. I think in the past few years we’ve seen institutions of media, we’ve seen institutions of government being complicit in genocide, manufacturing consent for genocide. And people are — feel deceived. They feel like they’ve been lied to.

And here we have a politician who is speaking to people’s politics, who’s speaking to people’s desires, not just on Palestine, of course, but cost of living, on economic issues, real leftist values. And he’s coming in and saying, “Actually, we understand what this is. This is all a narrative that’s fabricated. It’s a facade. We really have to deal with this reality, and we have to push forward the politics that represents our people.”

And actually, I think Palestine is central to this, and he understands that Palestine is central to this. And I don’t think that if the Gaza genocide hadn’t happened in the past two years, it wouldn’t have mobilized the base in such a way here that would have propelled his victory. I really think Palestine is central to Mamdani’s election victory.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to your book, Fire in Every Direction, a memoir, and your comments about putting out a memoir at this time, and yet the power of this magnificent book, talking about your life, your family’s life, from Amman to London to Palestine. Fire in Every Direction, why the title?

TAREQ BACONI: Well, the title is actually a phrase that I use to describe my mom in the book. My mom is an incredible activist and incredible woman and had, in her university years in Lebanon, been active on Palestine. This is before the Lebanese Civil War. My grandparents had been expelled in the Nakba in 1948 to Lebanon. And not a lot of people know this, but between ’48 and a few years after ’48, to ’51, I believe, Christian Palestinian refugees were getting naturalized, because the Lebanese government was playing with the demographics of the country. And so, my grandparents were naturalized. They were not in refugee camps. They got citizenship, and they became Lebanese citizens.

So my parents were born and raised in Lebanon as Lebanese citizens. And my mom was very active on Palestine, and during the Civil War fled to Jordan, where I was born. And she carried a lot of rage. I think it was rage that moved down to her from her own parents, from the Nakba, from the inability to achieve justice. And so, I describe her rage in the book as fire burning in every direction. And so, that’s really the — where the title comes from.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: So, Tareq, I mean, talk about the decision to write a memoir. When did you start writing it? And did you always know you would write a memoir? You’ve said, in another context, that it’s, quote, “either the bravest or the stupidest thing I’ve done.”

TAREQ BACONI: Yes, I mean, listen, I always knew that — well, I always knew that I had an impulse to write this book. Even when I was writing Hamas Contained, I knew that that wasn’t the book that I really wanted to be writing. And I started writing this book properly — I feel like I’ve been writing it my entire life, in some ways, but I started writing it properly in 2017. And I just could not have imagined it coming out at a moment of genocide. It was a really — it was a really difficult reality to sit with, understanding that, you know, there would be this memoir at a moment of genocide, when I feel like our collective gaze should be on Gaza. Every effort is trying to move us to look away from Gaza, and we should keep talking about Gaza.

And the more I sat with this, the more I realized that, actually, this is a book about the Nakba. This is a book about — you know, the genocide is the continuation of the Nakba in other ways. And this book is about the Nakba, about my grandparents, about my parents, about these structures of violence that have dispossessed and continue to dispossess Palestinians. And so, in some ways, I think that this is just one facet of our collective story as Palestinians.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: I think one of the things that’s extraordinary about the book, though, because it’s true there is — the whole story is told in the context of the politics of Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine. But what you do — and I’ll just read the comments of the acclaimed Palestinian writer Isabella Hammad, commenting on your book. She said, in the memoir, you refuse, quote, “to separate the story of sexual identity from the story of political commitment, and in so doing [model] a way to see our personal struggles as intertwined with our collective ones.” So, if you could elaborate on that, the many decisions you took in the writing of the book, what was included, what was excluded, and how you came to, don’t know, bring the two together so, political — the political and the personal?

TAREQ BACONI: Absolutely. I mean, listen, when I started writing this book, for me, this book, at its core, is a love story between two boys in Amman. That’s what this book is, and that’s what it had always been. When I wanted to write it, that’s what the initial impetus for the writing, the creative impulse, was to write a love story that I felt couldn’t be narrated when I was growing up. And I didn’t even consciously think that Palestine, or even the story of my grandparents or the Nakba, would be a part of it. And the more I wrote, the more I realized that there’s no story to be told here without telling the story of who I am as a person, and that’s the story of my grandparents, and that’s the story of my parents. And so, obviously, that became a very political book. And in some ways, I can understand that now, in retrospect, but I can’t say that it was a conscious decision at the time.

I also know that, intellectually, a lot of my work has come to understand Palestine through queer theory, as well, understanding how, you know, queerness is demonized, and certainly where I was coming from, and in many ways, Palestine is demonized here. And this is not a story of East-West. This is a story of silences, of how, you know, these structures of oppression or these structures of violence allow certain things to be said and not to be said. And so, the way that I came into my queer identity unraveled this whole idea of normative discourse that we have to accept and abide by, and pushed me to think about, you know, “What can you challenge. What are — what’s not being said? What are the silences that we’re comfortable with?” and to poke.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about your, what you’ve described as a complicated and unresolved relationship with the word “gay.” At one point, you even call it “revulsion.”

TAREQ BACONI: Yeah, I mean, I think this is a complicated history. I think many people have written on this. You know, the most famous book on this is obviously Joseph Massad’s Desiring Arabs, this idea that the LGBTQ+ labels have also been used by the West as part of empire, that this is — they go into these uncivilized, barbaric spaces, and they civilize. You know, they bring — they have a savior complex that they’re bringing in to save women or to save minorities or to save LGBT folk. Meanwhile, this is all a recipe for empire and for violence. And Israel does that exceedingly well, you know, this Tel Aviv is the capital of gay life, this pinkwashing, where, you know, if you’re gay or if you’re not gay, if you’re Palestinian, you’re living under apartheid. It doesn’t matter. But this is a civilizational discourse that’s embedded in these terms.

And so, being someone who grew up in Amman, you can’t really adopt this language without falling into the trap of then being seen as part of empire or part of this foreign invasion into one’s lands. And I think there’s a beautiful effort and movement among queer communities in the region to reclaim that language, to not accept it as part of that liberal discourse of the West, which is often a very violent discourse of empire, and to bring it back to a discourse of democracy and decolonization and freedom. So, I identify as a queer man today as part of a political project. It’s not just a sexual identity. It expands beyond that and rejects Zionism and rejects authoritarianism, and that’s part of my queerness.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: I mean, you said earlier that the book, it’s about silences, you know, at both — I mean, East and West, not exclusively one or the other, about Palestinian-ness in the West and about queerness in Jordan and the broader Middle East. I mean, in a way, your decision to write this as a memoir, rather than fiction, is another way in which you subvert that silence by fully assuming your voice.

TAREQ BACONI: Yes, and it was a difficult decision. That’s why I said it was either the stupidest or the bravest thing I’ve done, because it was — it was a difficult decision. I think there is literature coming out of the Middle East, certainly, fictional, but also some nonfiction, that’s engaging with questions of queerness. But for me, I always felt that I could write this as fiction. I could also write it as a pseudonym. And I think that would be a very important contribution. But I just knew that this wasn’t what I wanted to do. I wanted to — whatever — whatever it means for me socially and politically, it was important for me to say there is space for these narratives. We’re not a monolith, and there is space for these stories. And we need to be able to hold this. If we’re talking about liberation and we’re talking about emancipation and Palestine, what is that? That’s inclusive of everything. Obviously, it’s dismantling Zionism, but it’s also dismantling the patriarchy and homophobia and other forms of social oppression. And so, it felt to me that this was something that I needed to own.

AMY GOODMAN: And before we end, toward the end of your book, you talk about your decision to go to Palestine. Describe that journey.

TAREQ BACONI: So, I grew up in Jordan, and I was never allowed to go to Palestine, because there — for Jordanian men specifically, it’s very difficult to get visas to go to Palestine. And so, I had worked on Hamas Contained as part of my doctoral thesis for years before I had ever visited Palestine. And then, when I naturalized as a U.K. citizen in 2014, that was my opportunity to go back. You know, as I joke in the book, the colonial masters of my grandparents giving me permission to go into Palestine, which is, you know, now under the settler colony of Israel. And so, it was a — that was the first trip that I did with my — that I made with my U.K. passport.

And it was incredibly powerful, because it felt like I had grown up there. I had never been, but it felt like I had grown up there, the stories of my grandparents, my parents. And it was really important for me to go to Gaza, too. I didn’t spend enough time in Gaza. I wish I had been given more permission to do that.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Tell us what years, when you were there.

TAREQ BACONI: This was in 2015, 2015, so a few years after the Israeli military assault in the 2014 war. The devastation was extreme. I mean, now it seems relatively not as extreme as what we’re seeing today, but even then, it was shocking to see how the Israeli military assault sort of devastates neighborhoods in Gaza.

AMY GOODMAN: We want to thank you so much for being with us, Tareq Baconi, Palestinian analyst and writer. His memoir is just out. It’s called Fire in Every Direction, the president of the board of past — the president of the board of Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network, author also of the book Hamas Contained: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance.

=====

Up Next

“The World After Gaza”: Author Pankaj Mishra on Gaza & the Return of 19th-C. “Rapacious Imperialism”

===

요청하신 대로 타리크 바코니의 역작 <Hamas Contained>에 대한 심층 요약과 평론을 작성하고, 이어서 앞서 다룬 회고록 <Fire in Every Direction>과의 차이점을 정리해 드리겠습니다. 본문은 <해라> 체를 사용하여 작성했습니다.

1. <Hamas Contained> 요약: 저항과 봉쇄의 정치학

탄생과 이중적 구조

타리크 바코니는 하마스를 단순히 종교적 광신주의 집단으로 치부하는 서구의 시각을 정면으로 반박하며 글을 시작한다. 하마스는 1987년 제1차 인티파다의 산물로, 무슬림 형제단의 사회적 서비스 네트워크인 <다와(Dawa)>와 무장 투쟁 기구인 <알카삼 여단>이라는 이중 구조를 통해 팔레스타인 민중 속에 뿌리를 내렸다. 바코니는 하마스가 세속적인 파타(Fatah) 당의 부패와 오슬로 협정의 실패라는 토양 위에서 대안 세력으로 성장했음을 증명한다.

2006년 선거와 통치의 딜레마

책의 전환점은 2006년 팔레스타인 총선이다. 하마스의 승리는 국제 사회와 이스라엘에 충격을 주었으며, 이후 가자 지구는 물리적으로 고립된다. 여기서 바코니는 하마스가 직면한 근본적인 모순을 지적한다. 하마스는 점령에 맞서는 <저항 운동>인 동시에, 가자 지구 시민들의 생존을 책임져야 하는 <통치 기구>가 되었다. 이스라엘은 가자를 봉쇄함으로써 하마스가 통치 역량에만 에너지를 쏟게 만들었고, 이를 통해 그들의 저항 에너지를 소모시키려 했다.

봉쇄(Containment)라는 전략적 틀

바코니가 제시하는 핵심 개념은 <봉쇄>다. 이스라엘은 하마스를 완전히 궤멸시키는 대신, 가자 지구라는 거대한 감옥 안에 가두어 두는 전략을 취했다. 이는 팔레스타인 정치를 가자와 서안지구로 분열시켜 팔레스타인 국가 수립 가능성을 차단하려는 이스라엘 우파의 전략적 계산과 맞닿아 있었다. 하마스 역시 이 봉쇄의 틀 안에서 때로는 무력 도발을 통해 협상력을 높이고, 때로는 휴전을 통해 통치의 안정을 꾀하며 생존해 나갔다.

폭력의 순환과 한계

저자는 하마스와 이스라엘 사이의 반복되는 군사적 충돌을 <풀 베기(Mowing the grass)> 전략으로 설명한다. 이스라엘은 압도적인 화력으로 하마스의 역량을 주기적으로 깎아내리고, 하마스는 그 참상을 바탕으로 대중적 지지를 결집한다. 바코니는 이 비극적인 공생 관계가 결국 팔레스타인 민중의 고통만을 가중시켰으며, 근본적인 정치적 해결 없이는 이 <봉쇄>가 시한폭탄과 같음을 경고한다.

2. 평론: 신화를 걷어낸 냉정한 분석

분석적 중립성의 가치

바코니의 학술적 성취는 하마스를 선악의 구도로 보지 않고 <합리적 행위자>로 분석했다는 데 있다. 그는 하마스의 이데올로기적 경직성과 전략적 유연성을 동시에 조명함으로써, 이 조직이 왜 그토록 오랫동안 소멸하지 않고 살아남았는지를 설득력 있게 설명한다. 이는 중동 정책 결정자들에게 하마스를 무시하거나 맹목적으로 공격하는 것이 얼마나 비효율적인지를 일깨워주는 강력한 비판이다.

구조적 폭력에 대한 고발

이 책은 하마스의 폭력만큼이나 이스라엘이 구축한 <구조적 봉쇄>의 폭력성을 날카롭게 파헤친다. 봉쇄는 단순한 방어 기제가 아니라, 한 민족의 자결권을 박탈하고 그들을 항구적인 인도주의적 위기 속에 몰아넣는 능동적인 가해 행위임을 바코니는 논리적으로 입증한다.

예견된 파국

책의 결론에서 느껴지는 통찰은 소름 끼칠 정도로 정확하다. 바코니는 봉쇄가 영원할 수 없으며, 압력이 임계점에 도달하면 폭발할 것임을 예견했다. 2023년 10월 7일의 사건은 바코니가 이 책에서 경고했던 <봉쇄 전략의 파산>을 가장 비극적인 형태로 보여준 사례라고 할 수 있다.

3. <Hamas Contained> vs <Fire in Every Direction> 차이점

| 구분 | Hamas Contained (2018) | Fire in Every Direction (2024/25) |

| 장르 | 학술적 분석서 / 정치 평론 | 개인적 회고록 / 에세이 |

| 관점 | 외부적·객관적 관찰자 (Scholar) | 내부적·주관적 당사자 (Palestinian) |

| 주요 대상 | 하마스 조직, 이스라엘의 봉쇄 정책 | 저자 자신의 삶, 디아스포라의 고통 |

| 톤(Tone) | 냉철함, 논리적, 데이터 중심 | 감성적, 실존적, 성찰적 |

| 지식인의 태도 | 정책적 대안과 구조적 분석 제시 | 분석의 무력감 고백, 증언과 공감 촉구 |

| 시간적 배경 | 하마스의 기원 ~ 2010년대 중반 | 유년기 ~ 2023년 10월 이후의 비극 |

요약하자면

<Hamas Contained>가 팔레스타인 문제라는 거대한 기계의 작동 원리를 파헤친 설계도라면, <Fire in Every Direction>은 그 기계에 짓눌려 살아가는 사람들의 비명과 저자 자신의 심장 박동을 기록한 일기와 같다. 전자가 독자의 <이성>에 호소하여 상황의 복잡성을 이해시킨다면, 후자는 독자의 <감성>에 호소하여 상황의 비극성을 체감하게 만든다.

바코니의 두 저작을 통해 팔레스타인 문제를 입체적으로 이해하시는 데 도움이 되었으면 합니다. 혹시 바코니가 최근 언론 기고문에서 이 책들의 논의를 어떻게 업데이트하고 있는지 추가로 알고 싶으신가요?

Hamas Contained: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance Kindle Edition

by Tareq Baconi (Author) Format: Kindle Edition

4.4 4.4 out of 5 stars (101)

Part of: Stanford Studies in Middle Eastern and Islamic Societies and Cultures (51 books)

"Judicious and impartial, this important work adds nuance to the portrait of one of the Middle East's most divisive players" (Publishers Weekly).

Hamas is a multifaceted liberation organization that rules Gaza and the lives of the two million Palestinians who live there. Demonized as a terrorist group in media and policy debates, it has been subjected to accusations and assumptions that have helped justify extreme military action in the region. In Hamas Contained, Tareq Baconi offers the first history of the group on its own terms.

Drawing on interviews with organization leaders, as well as publications from the group, Baconi maps Hamas's thirty-year transition from fringe resistance to governance. Questioning the conventional understanding of Hamas, he shows how the movement's ideology ultimately threatens the Palestinian struggle and, inadvertently, its own legitimacy. Baconi demonstrates how Hamas's armed struggle has failed in the face of a relentless occupation, and he argues that Israel's approach of managing rather than resolving the conflict has neutralized Hamas's demand for Palestinian sovereignty. This dynamic has perpetuated a deadlock characterized by its brutality—and one that has led to the collective punishment of millions of Palestinian civilians.

==

No comments:

Post a Comment