김정은의 교육

김정은의 교육JUNG H. PAK2018 년 2월English

2011년 12월 북한 조선중앙통신이 지도자 김정일이 “과로”에 의한 심장마비로 70세의 나이로 사망했다고 보도했을 당시 나는 미중앙정보국의 비교적 신참 정보분석가였다. 김정일의 심장에 문제가 있다는 것은 누구나 알고 있었다. 그는 2008년에 뇌졸증을 앓았고 흡연, 음주, 파티하기등의 생활습관이나 심장병이란 가족력을 볼 때 언젠가는 심장에 문제가 있을거라는 것은 예상할 수 있었다. 김정일의 아버지이며 북한의 창립자인 김일성 또한 1994년 심장마비로 사망하였다. 그럼에도 불구하고 김정일의 죽음은 충격으로 왔다.

진심이든 아니든 북한 주민들이 울고 기절하고 슬픔에 싸여 있을 때, 김정일의 아들 스물살남짓한 김정은은 국경을 폐쇄하고 비상사태를 선언했다고 전해졌다. 이러한 소식은 김정일 사망전에 북한으로 밀반입된 핸드폰을 통해 외국 언론에 알려진 것이었다.

2011년 이전에도 김정일이 그의 아들을 후계자로 키우고 있다는 조짐은 이미 있었다: 김정은이 아버지와 함께 공개적으로 군부대 시찰에 동행하기 시작하였고, 그가 태어난 집이 유적지로 지정되었으며 북한군과 당, 그리고 보안국의 높은 직책과 역할을 맡기 시작하였고 2010년에는 4성장군이 되었다.

김정일 사망 당시 한국은 국가안전보장회의를 소집하여 군과 민방위 경계태세를 높였고, 일본은 위기관리팀을 구축하였으며, 백악관은 미국이 “동맹국인 한국과 일본과 긴밀히 접촉하고 있다”는 성명을 발표하였다. 그 때 나는 랭리에 있는 CIA본부에서 불안정의 징후가 있는지를 살피면서 상황에 대한 나름대로의 생각을 구축하며 북한이 새 지도자하에서 어떤 방향으로 가게 될지를 나름 분석하기 시작했다. 김정일 사망 발표 즉시 조선중앙통신은 김정은이 후계자라는 것을 분명히 하였다: “ 오늘 우리 혁명의 진두에는 주체혁명위업의 위대한 계승자이시며 우리 당과 군대와 인민의 탁월한 령도자이신 김정은동지께서 서계신다…”

김정은은 어떤 사람일까? 북한 지도자라는 부담을 과연 원하는 걸까? 만일 원한다면 통치와 외교는 어떤 식으로 할까? 그가 계승하게 된 핵무기 프로그램은 어떻게 접근할까? 엘리트층이 김정은을 받아들일까? 혹시 불안정, 대규모 탈북, 난민 이동, 피비린내나는 숙청 또는 구테타가 일어나는 것은 아닐까?

북한과 아시아 전문가들 중에는 그가 곧 물러나거나 쫓겨나거나 끝날 것이라고 예측하는 이들이 많았다. 20대중반에 지도자 경험도 전무하니 나이많은 이들에게 곧 제압당해 정권을 빼앗길 것이라고 본 것이다. 게다가 북한 주민들이 공산주의에서는 선례가 없는 두 번째의 권력계승을 받아들이지 않을것이며 나이와 경륜을 높이 사는 사회에서 그의 어린 나이는 치명적 약점이기도 했다. 만일 김정은이 권력을 놓치 않는다면 북한은 어떻게 될까? 북한은 가난한 후진국으로 고립돼 있었고 주민들이 굶는 마당에 정통성과 영예를 위해 핵과 미사일 프로그램을 붙들고 있었다. 김정은하에서 북한의 멸망은 그 어느 때보다 가능성이 높아 보였다.

그건 그 때의 얘기다.

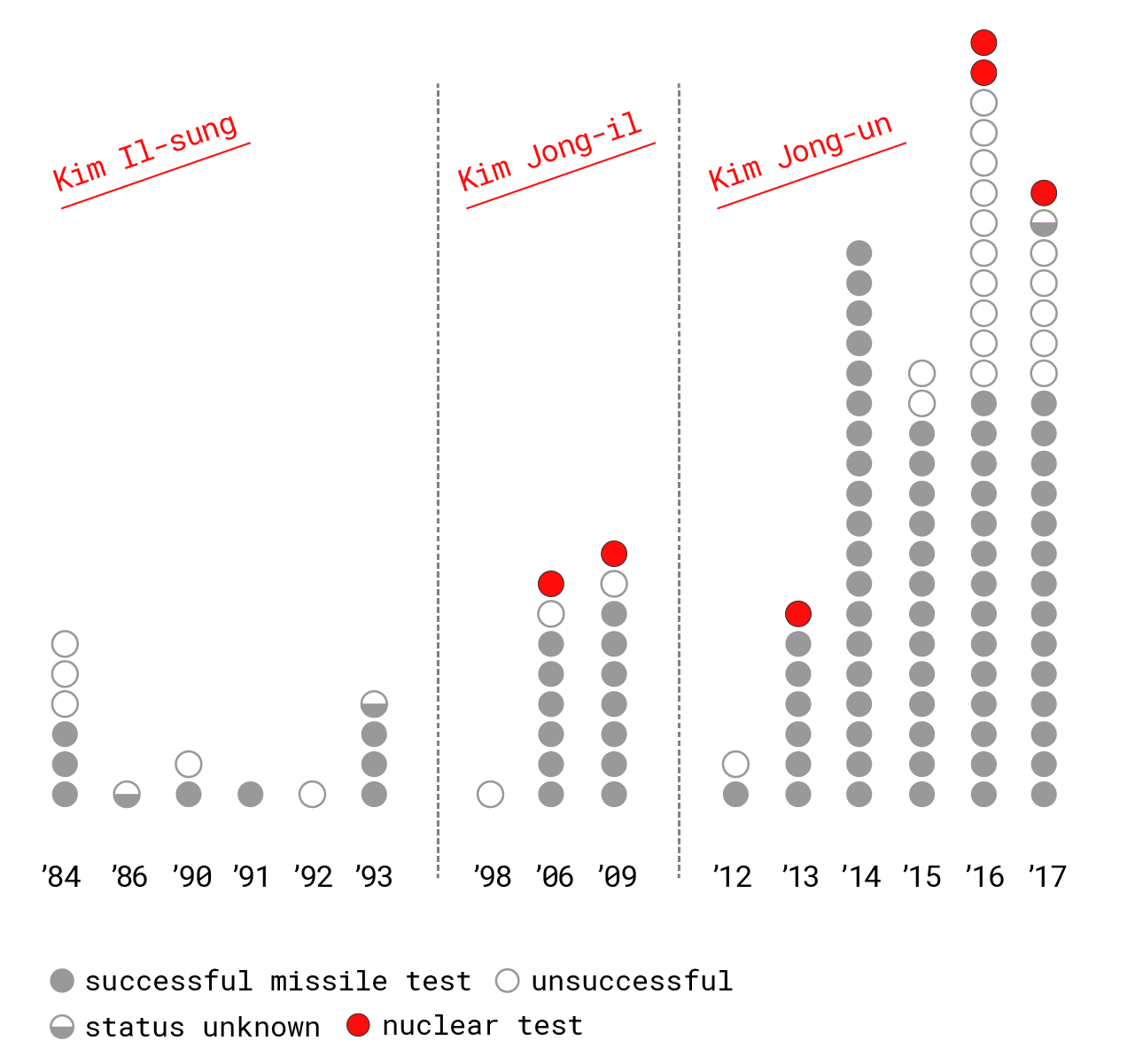

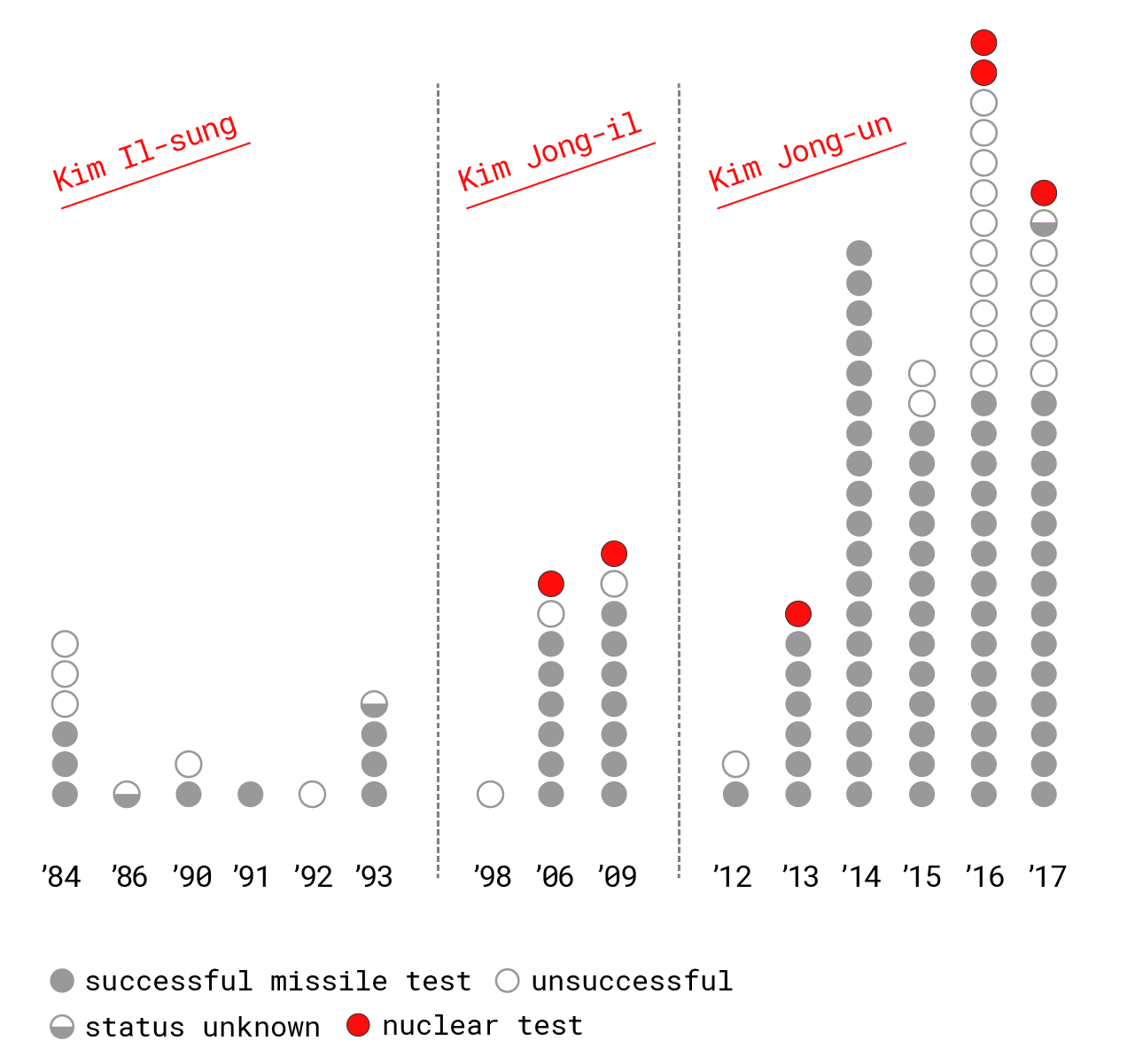

6년이 지난 지금, 김정은은 다양한 호칭을 추가하면서 북한 지도자로서의 위치를 굳혔다. 김정은하에서 북한은 6차례 핵실험중 4개를 단행하였고 가장 큰 핵실험인 2017년 9월 핵실험은 100 – 150 킬로톤의 위력을 가진 것으로 추청되고있다 (2차대전중 일본 히로시마에 투하된 핵폭탄의 위력은 15 킬로톤으로 추정된다.) 그는 또한 90 여개의 탄도미사일을 발사하였는데 이는 그의 아버지와 할아버지가 한 것보다 세 배나 더 많은 수이다. 북한은 현재 20 – 60 개의 핵무기를 가지고 있으며 미국 본토 타격 능력이 있는 듯한 대륙간 탄도 미사일(ICBM) 도 시현한 바 있다. 이대로 갈 경우 이르면 2020년에는 작전가능한 백여개의 핵무기와 여러 종류의 미사일을 – 장거리, 이동식, 잠수함발사 미사일 – 보유할 수 있다. 김정은하에서 북한은 주요 사이버공격을 감행하였고 국제공항에서 자신의 이복형을 화학신경물질로 살해한 것으로 보도된다.

지난 6년동안 김정은은 또한 북한에 스키장과 워터파크, 고급 레스토랑을 여는 등 국내외에 북한이 현대적이고 잘 산다는 모습을 보여주려 하였다. 이는 경제와 핵능력을 동시에 발전시키겠다는 병진정책의 일환으로 북한 주민들을 잘 살게 해주겠다는 자신의 약속을 지키는 동시에 외국인 관광객을 끌어들이기 위한 것이었다.

그러나 빠른 속도로 북한을 현대화시키는 와중에 김정은은 북한을 더욱 고립시키고 있다. 대화재개를 원하는 미국, 한국, 중국의 시도를 묵살하고 어떤 외국 정상과의 만남도 거부했으며, 지금까지 알려진 바로는 북한 지도자가 된 이후 의미있는 외국인과의 접촉은 일본인 요리사 겐지 후지모토와 미국 농구선수 데니스 로드만인데 겐지 후지모토는 김정은이 어렸을 때 알았던 사람으로 그가 2012년 평양으로 초대하였고 데니스 로드맨은 2013년 이후 북한을 5번 방문하였다.

김정은은 사라지지 않을것이다.

3 미터 키의 어린이

북한은 소위 CIA 가 보는 “힘든 타겟중에 가장 힘든 타겟”이다. 전 CIA 분석가가 말하기를 북한을 이해하려는 것은 마치 “몇 가지 조각을 가지고 퍼즐을 맞춰보려고 하는데 상대편이 일부러 다른 퍼즐에 있는 조각을 나한테 던져주고 있는 것과 같다”고 얘기한 바 있다. 북한 정권의 폐쇄성, 자발적인 고립, 탄탄한 정보 관행, 공포와 피해망상적인 문화 덕분에 우리가 얻는 정보는 매우 단편적인 것뿐이다.

정보분석은 어렵고 비직관적이다. 정보분석가는 모호성과 모순을 받아들여야 하고 가정을 계속 의심하고 다른 가설과 시나리오를 고려하며 많은 경우 중요한 상황에서 충분한 정보없이 결정을 내려야한다. 이러한 사고의 습관을 길들이기 위하여 정보분석가에게 사고 향상 코스는 필수이다. 전현직 CIA 정보분석가의 사무실에 가면 누구나 리처드 호이어 (Richards Heuer)가 쓴 얇고 자주색의 “정보분석의 심리학”이라는 책을 가지고 있다. 이 책은 CIA 분석가들의 필독서이다. CIA 신입사원 교육시에 제공되며 그 이후 교육에도 많이 인용된다. 이 책은 아직도 내 브루킹스 사무실 책상에서 손을 뻗으면 집을 수 있는 곳에 꽃혀 있다. 어쩌다 이 책에 눈길이 가면 나는 겸허함이 정보분석에 있어서 얼마나 필수적인지 – 특히 북한과 같은 목표물일 경우에 – 상기하게 된다. 왜냐하면 불확실한것을 깨닫게 해주고 내가 아는 것을 어떻게 알게 되었는지 상기시켜주며, 내가 내린 평가에 대해 확신이 있는지 묻게 하며, 내가 모르는 것들에 의하여 내 생각이 어떻게 바뀔수 있는지 평가하게 되기 때문이다.

저자 호이어는 CIA 에서 작전및 분석가로 45년간 근무하였으며, 이 책에서 정보분석가들이 어떻게 사고 프로세스가 가진 약점과 편견들을 극복하고 적어도 이를 인식하고 관리할 수 있는지를 다루고 있다. 그의 중요 논점중의 하나는 우리는 보통 우리가 인식할것으로 기대하는 것들을 인식하며, 이러한 “기대의 패턴에 의하여 분석가들은 무의식적으로, 무엇을 보아야 하는지, 무엇이 중요한지, 또 본 것을 어떻게 해석할지를 정한다는 것이다.” 분석가들이 이미 가지고 있는 생각에 의하여 일정한 방식으로 생각하게 되며 이는 새로운 정보를 활용하는 데에도 영향을 미친다는 것이다.

그렇다면 김정은과 그 정권에 대한 정확한 평가를 내리려면 어떠한 고정된 기대치와 인식을 극복해야 하는걸까? 북한 중앙통신의 지나치게 과장된 표현들과 김정은의 황당한 발언들, 또 사회주의 예술에서 보여지는 과장되면서도 진부한 이미지를 보면 김정은을 우스꽝스러운 인물로 폄하하기 쉽다. 하지만 그것은 실수이다.

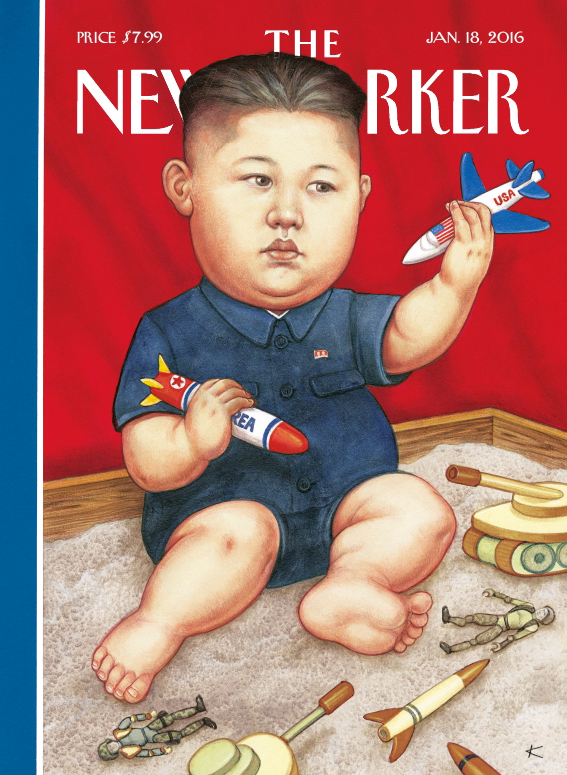

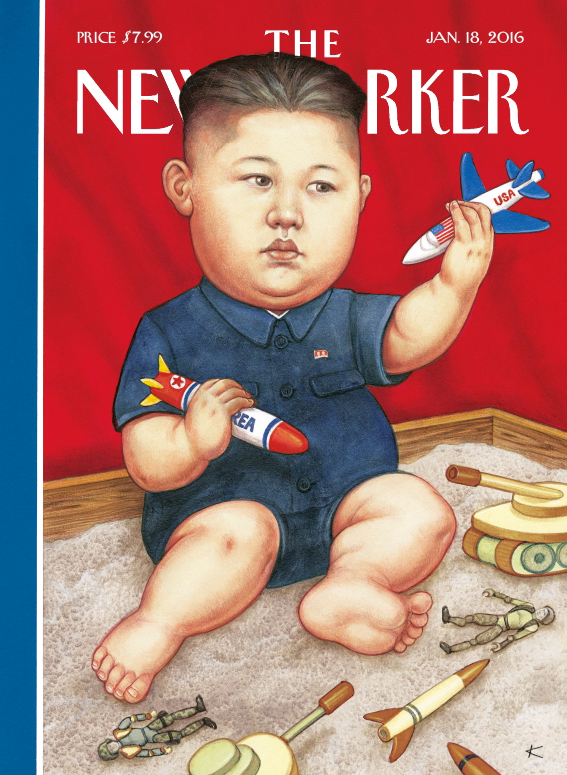

김정은의 외모에 초점을 맞추게 되면 그의 체중이나 젊음을 비하하며 만화의 인물로 희화화하는 경향이 있다. 미국 대통령을 비롯해서 여러 매체들은 김정은을 “로켓맨,” “작고 뚱뚱한,” “미치광이 뚱뚱한 아이,” “평양의 돼지소년”등으로 불렀다. 북한의 4차 핵실험이 있은 뒤인 2016년 1월 18일 뉴요커 잡지의 표지는 김정은을 뚱뚱한 아기로 그리면서 핵무기, 탄도미사일과 탱크등의 “장난감”을 가지고 노는 것으로 그리고 있다. 이 그림은 김정은이 마치 어린아이처럼 떼쓰고 변덕스럽고 이성적인 판단이 불가능하며 자신과 다른 사람들을 곤경에 빠뜨리는 인물이라는 것을 시사하고 있다.

그러나 우리의 초점을 무섭게 빠른 속도로 발전하는 북한의 사이버, 핵, 재래식능력에 맞추게 되면, 김정은은 엄청난 무제한의 힘을 가진, 막을 수도 없고 억제할수도 없는 전지전능한 3 미터 의 거인이 되는 것이다.

이 두 가지 인식의 공존 – 즉 3 미터 키의 어린이 – 라는 관점이 김정은과 북한에 대한 우리의 이해와 몰이해를 가져왔던 것이다. 이는 김정은의 능력을 동시에 과소평가 또 과대평가하게 하고, 그의 의도와 능력을 동일시하며, 그가 이성적인지 의심하고, 그가 전략적인 목적을 가지고 있다거나 그 목적을 달성할수 있는 수단이 있다고 가정하게 만든다. 이러한 가정들이 우리의 정책 논의를 왜곡시키는 것이다.

김 장군의 발걸음

만일 한국의 관습과 전통을 따랐다면 김정일은 세 아들 중 김정은이 아닌 첫째 아들 김정남을 후계자로 삼았을 것이다. 그러나 김정일은 김정남이 지도자감이 아니라도 생각했다. 왜일까? 김정일은 어쩌면 김정남이 외국물에 오염되었다고 판단했을 수 있다. 2001년 김정남은 위조여권으로 동경 디즈니랜드에 가려다가 붙들렸었다. 그 보다 더 심각했던 것은 그가 북한이 정책개혁을 통하여 서구에 개방해야 한다고 건의했다가 아버지 김정일의 노여움을 샀다고 한다.

둘째 아들 김정철은 너무 유약한 것으로 보았다; 김정철의 친구중 한 사람의 말로는 “(정철)은 다른 사람을 해칠 수 있는 사람이 아니다. 절대 악당이 될수 없는 착한 사람이다.” 김정철은 자기 동생의 정권에서 불특정한 보조 역할을 하고 있는 듯 하다.

이렇게 해서 김정일이 북한 지도자로 선택한 아들이 김정은이었는데 아들중 가장 공격적이었기 때문이다. 김정일의 전 스시 요리사였던 겐지 후지모토는 김정은의 초대로 평양을 방문하기도 했는데, 후지모토는 김정은과 그의 아버지의 관계에 대하여 직접 목격한 매우 흥미로운 얘기를 전한다. 후지모토에 따르면 김정일이 막내아들 김정은을 후계자로 결정한 것은 이미 1992년이었다고 주장한다. 그 증거로 김정은이 아홉살 되는 생일파티에서 김정일이 밴드에게 “발걸음” 을 연주하게 하고 그 노래를 김정은에게 바쳤다고 한다: 척척척; 우리 김대장 발걸음; 2월의 정기 뿌리며 앞으로 척척척 (김정일의 생일이 2월이다); 온나라 인민이 따라서 찬란한 미래를 앞당겨 척척척. 가사로 미루어보건대 김정일은 김정은이 자기 아버지의 정신과 전통을 이어받아 북한을 미래로 이끌것으로 기대한 듯 하다.

김정일이 자기 아들을 왕조를 계승할 후계자의 자질이 있다고 생각했을지 모르나 김일성과 김정은, 그리고 김정은 사이에는 중요한 차이점들이 있다. 북한의 시조이자 김정은의 할아버지인 김일성은 1994년 사망할때 까지 거의 50년간 북한을 통치하였으며 일본 제국주의와 남조선 “꼭두각시들,” 또 미국 “승냥이”에 맞서서 정전협정에 의거하여 전쟁이 끝날 때까지 싸운 혁명 영웅이었다.

그 다음 세대 김정일은 급변하는 세계 정세를 헤처가야만 했는데, 소련의 붕괴와 그에 따른 소련의 대규모 원조가 끊겼고, 한국과의 관계를 우선시하는듯한 의심스런 중국과의 관계 변화, 또 북한 핵프로그램의 시작에 따른 미국과의 힘든 협상등을 거쳐야 했다. 게다가 1990년대의 대기아와 가뭄이 있었고 점점 옥죄오는 제재조치와 국제적인 고립등에 대처해야만 하였다.

어려움에 단련된 그의 조상들에 비하여 김정은은 사치와 특권에 보호되면서 자랐다.

1990년대 대기근 동안 약 2~3백만 북한 주민이 아사와 굶주림 관련 질병으로 죽어갈 때 김정은은 스위스에 있었다. 그의 어린 시절은 사치스러웠고 편안했다: 말이 있는 큰 저택, 수영장, 볼링장, 개인 별장에서의 여름, 7살짜리가 운전할 수 있게 고친 고급 승용차. 김정은에게 스위스 알프스에서 스키를 타고 프랑스 리비에라 해변에서 수영하는 것은 타고난 특권으로 여겨졌을 것이다. 김정은은 욱하는 성격이었고 지는 것을 싫어했으며 할리우드 영화와 농구 선수 마이클 조단을 좋아했다.

후지모토 요리사는 김정은의 모친이 교육에 그리 엄하지 않았던걸로 얘기하였으며 억지로 공부를 한 적은 없다고 한다. 스위스에서의 그의 친구이자 동급생은 김정은에 대해서 “우리는 반에서 제일 똑똑하지는 않았지만 제일 공부를 못하지도 않았다. 우린 항상 이류였다..선생들은 힘들어하는 김정은을 가만 놔두는 편이었다.” 김정은은 성적이 그리 좋지 않은 것에 신경을 쓰지 않았다; 같은 반 친구는 말하기를 “그는 시험 성적이 나오기도 전에 떠났다. 그는 공부 보다 축구와 농구에 더 관심이 많았다.”

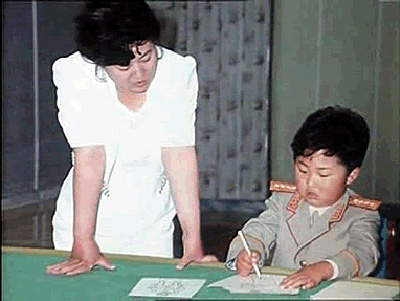

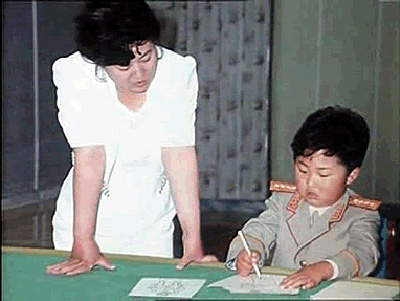

공부를 열심히 한 편은 아니었지만 김정은은 어릴때부터 아버지로부터 선택되어 지도자가 될 것을 알았던 것 같다. 그의 강한 자존심과 자신감은 아주 어렸을 때부터 길러졌다. 전체주의 정권인 김왕조는 어린 소년을 중심으로 숭배주의적 환경을 조성하였고 이는 그의 아버지와 할아버지때도 마찬가지였으며 거기에 공포와 협박 그리고 힘의 과시가 더해져 더욱 강화된다. 김정은의 이모에 의하면 그는 여덟살 생일파티에서 별을 단 장군복을 입었으며 진짜 별을 단 장군들이 그에게 경례를 하며 존경심을 표했다고 한다. 후지모토에 따르면 김정은은 11살때 콜트 45 권총을 차고 다녔으며 군복을 입었다고도 한다.

마크 보우든이 2015 베니티 페어 프로파일에서 썼듯이 “다섯살 때 우리는 모두 우주의 중심이다. 부모님, 가족, 집, 이웃, 학교, 나라등 모든 것이 우리를 중심으로 돈다. 대부분의 사람들에게 그 이후의 여생은 천천히 왕좌에서 물러나는 과정으로써, 어린 폐하는 점점 더 분명하고 겸허한 진실에 눈을 뜨게 된다. 그러나 김정은은 아니었다. 다섯살 때의 세계는 30세인 그의 세계이기도 하다… 모든 사람이 그를 위해서 존재한다.”

따라서 소수의 스승, 가정교사, 요리사, 지정된 친구들, 경호원, 친척과 기사들이 김정은에게 권리의식을 강화시키고 북한의 현실에서 그를 보호한 반면에, 주체사상과 수령 개념은 그가 지도자 자리를 승계 받을 때 사상적 실존적 당위성을 제공하였다. 북한의 선전기관은 그의 지혜와 용맹 그리고 세살 때부터 운전을 하였다는 초인적인 능력등 그에 대한 전설을 만들어 알리기 시작하였다.

2006년 10월, 김정은이 20대초 김일성군사종합대학을 졸업하기 두 달전 (2002년부터 다녔다고 알려지는), 북한은 첫 핵실험을 하였고 이는 김 왕조에 또 하나의 보호막을 제공하면서 최고의 힘을 가진 김씨 가족의 신화를 더 심화시키고 젊은 김정은의 현실감각과 기대치를 더욱 왜곡시킨다. 그 핵 실험과 그의 아버지와 할아버지의 핵무기에 대한 집념은 권력을 잡게 된 김정은의 선택의 폭을 좁게 만들었으며, 조국의 운명과 이천오백만 북한 주민이 그가 이 전통을 밀고 나가는데 달려있다고 믿게 만든다. 젊은 김정은과 군사대학의 동료들은 – 미래의 군 엘리트 – 분명 핵실험이라는 이정표에 축배를 들면서 북한의 핵미래를 긍정적으로 생각하였을 것이며 자신들이 조국의 미래를 방어할 것이라는 굳은 믿음을 가지게 되었을 것이다.

김정은이 지도자가 되고 북한의 국익을 대표하게 되자 그에게 자기 아버지와 할아버지때 억압을 가능케 했던 모두 정치적 도구가 주어졌다. 이 도구들은 실제 또는 의심스런 반대파들을 제거하는데 사용되었고 고문과 강간, 그 외 다양한 인권침해가 수십년동안 자행되고 지금까지 이어지는 끔찍한 수용소들을 유지하는데 사용되었다. 유엔 북한인권이사회가 2014년 발표하였듯이 북한은 “체계적이고 광범위하며 끔찍한 인권침해”를 자행하였고, “김일성-김정일주의”의 기치하에, 북한 정권은 “주민들 삶의 모든 면을 지배하고자 하며 내부로부터 공포에 떨게 하고 있다.”

21세기 독재자

정보분석가로 일하기 전 미국역사를 연구한 학자로서, 김정은이 삼대세습으로 북한을 장악하였을 때 나는 앤드류 카네기가 미국의 3 대에 대해 했던 말을 기억하지 않을 수 없었다. “부자가 삼대를 가지 못한다.” 즉, 1대는 돈을 벌고, 2 대는 이를 유지하고, 3 대는 돈을 모두 날려버린다는 것이다. 김정은은 그렇게 되지 않기 위해 애를 쓰고 있는 듯 하다.

김정은은 북한의 시조인 할아버지 김일성과 아버지 김정일이 죽을 때까지 그리고 죽고 나서도 유지했던 신비롭고 신적인 지도자의 역할을 채택하였다. 그러나 동시에 자신의 방식으로 통치 하겠다는 모습을 보인다. 즉, 이것은 당신 할아버지의 독재 방식이 아니라는 것이다.

그는 1990년 대기아가 오기 전의 또 소련이 붕괴되기 전의 할아버지 시대의 향수를 이용하고 있다. 할아버지를 닮은 모습과 분위기를 가진 그는 북한 주민들의 김일성에 대한 애정을 기술적으로 활용한다. 북한의 최고지도자로 오른지 몇 달 후 김일성 탄생 100주년을 기념하는 자리에서 김정은은 첫 공개연설을 한다. 긴 20여분짜리 연설에서 그는 할아버지의 전통을 상기시키고 아버지의 “선군” 정책을 재확인하면서 “적군이 핵폭탄으로 우리를 위협하던 날들은 영원히 사라졌다” 고 선언한다. 자기 아버지의 정책을 지지하면서도 그는 아버지와는 확실히 관행을 달리하였는데, 왜냐하면 김일성 이후 북한 주민들이 지도자의 목소리를 들은 것은 이 때가 처음이었기 때문이다. 김정일은 거의 20년간 통치하였으나 대중 연설은 기피하였다.

할아버지에 대한 향수를 맘껏 즐기면서도 김정은은 “현대적인 북한”의 “현대적인 지도자”로 보이고자 애쓴다. 자신만의 방식에 대한 의지는 아버지와 다른 대외 이미지를 추구하는 데에서도 볼 수 있다. 김정은은 아버지보다 더 투명하고 접근가능한 것으로 보이고자 한다. 그는 예쁘고 세련된 젊은 아내 리설주와 (함께 적어도1명에서 3명정도 아이를 낳은) 공개석상에 나타난다. 그는 남자, 여자, 어린이들과 포옹하고 손잡고 팔짱을 끼며 나이에 상관없이 편하게 대한다. 투명성은 정부에서도 볼 수 있다. 2012년 4월 위성발사중 하나가 실패했을 때, 북한 정권은 사상 처음으로 실패를 공개적으로 인정하였다.

빈번한 공개 활동중에 김정은은 자기 아버지와 할아버지가 그랬던것처럼 경제, 군사, 사회 및 문화행사에서 지도를 하는 것을 볼 수가 있다. 그러나 이뿐 아니라 풀도 뽑고, 청룡열차도 타고, 탱크도 몰고, 말도 타는 것을 볼 수 있다. 그는 핸드폰과 랩탑 정도의 기술에 익숙하며, 핵과학자들과 진지하게 대화를 나누고 여러 번의 미사일 시험을 관장하기도 한다.

김정은은 자신이 젊고 활기차고 행동하는 사람으로 보이길 원하며 자신의 조국도 그렇게 될 것으로 생각한다. 2012년 4월 최고지도자가 된 후 북한 주민들에게 하는 첫 공개연설에서 그는 북한 주민이 더 이상 허리띠를 졸라매지 않을 것이라고 자신있게 약속했다. 그 후 그는 병진노선 정책을 발표하였다: 즉 핵무기와 경제 번영을 동시에 가질 수 있다는 것이다. 특권을 가진 자의 뭐든지 가능하다고 믿는 낙관주의를 기반으로 김정은은 이 두 가지를 최우선으로 정하고 이를 개인적으로 자기 것으로 만든다. 이 모든 것은 본인의 브랜드를 만들고 키우는 목적의 일환이다.

북한 정권이 선택하고 알리기로 한 김정은의 찬란한 일대기를 보면 김정은이 북한의 미래를 어떻게 상상하고 있으며 그 속의 자신의 위치를 볼 수 있다. 김정은의 아내 리설주의 대외 활동은 잘 계산된 것으로, 정권의 “부드러운” 면을 보여주면서 멋스러움과 유머로 북한 주민들이 견뎌야 하는 잔혹함과 굶주림, 그리고 박탈감을 얇게 가리고 있다. 또 김정은과의 사이에서 여러 명의 아이가 있다는 보도는 김 왕조를 승계할 아들을 낳을 가능성과 다산을 시사하기도 한다 (물론 김정은의 “현대적인” 경향을 보았을 때 딸에게 정권을 물려줄 가능성도 배제할 수 없다.) 억압받는 북한 주민들에게나 엘리트층에게나 멋지고 좋은 아내인 리설주는 부러운 인물임에 틀림없다.

외부 학자들에게 리설주의 공개 활동은 또 다른 의미가 있다 – 김정은이 적극적으로 홍보하는 듯한 물질과 소비 문화의 등장이 바로 그것이다. 2017년 여름과 가을에 걸친 제 6차 핵실험과 여러 번의 탄도미사일 발사로 인하여 미국과의 긴장이 최고조에 달한 와중에도 북한의 국영매체는 김정은과 그 아내의 화장품회사 방문 영상을 보여주었다. 그는 화장품 산업이 “세계적인 경쟁력”을 가질 것을 장려하면서 아름다움에 대한 여성들의 꿈을 도와주는 것을 치하하고 포장에 대해 자신의 생각을 얘기하기도 하였다.

뷰티 산업에 더불어 김정은이 경제개발의 비전의 일환으로 추진하는 것들은 스키장, 경마장, 스케이트장, 놀이공원, 새로운 공항, 돌고래 수족관등이 포함되어 있는데 아마 이러한 시설들이 김정은에게는 “현대적인” 국가의 표식으로 여겨지기 때문인 듯 하다. 아니면 자신이 누렸던 것들을 일반 주민들도 누리길 바라는 순수한 마음일 수도 있다. (후지모토에 따르면 김정은이 18세였을 때 이렇게 말했다고 한다. “우리는 여기서 농구도 하고 말도 타고 제트스키도 타고 재미있게 놀고 있다. 하지만 보통 사람들의 삶은 어떨까?”)

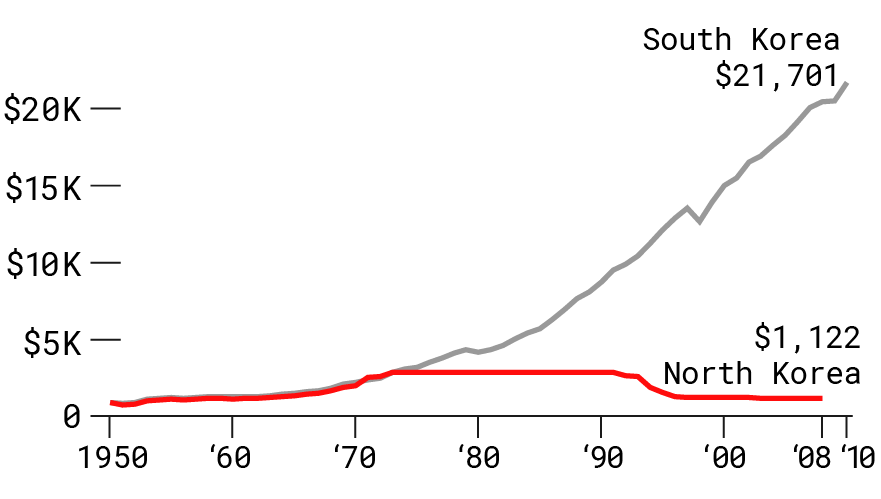

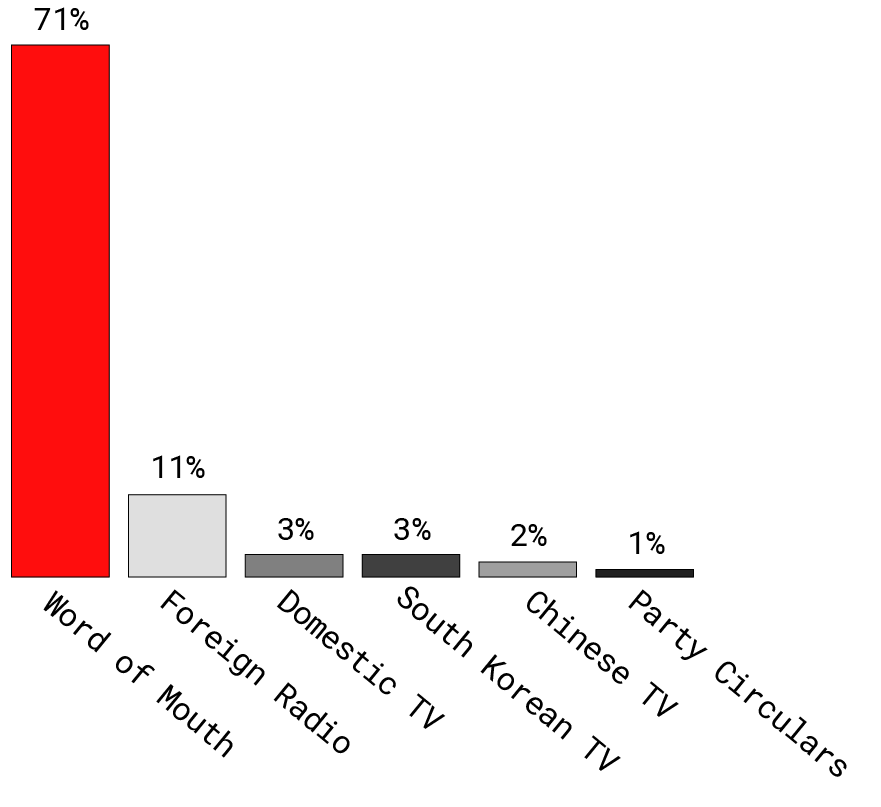

김정은은 또한 이런 현대적인 시설들을 보여줌으로써 보통 북한하면 떠올리는 낙후되고 굶주리고 경제적으로 결핍된 모습을 지우려는 것일 수도 있다. 어쩌면 이보다 더 중요한 이유는 남한의 물질적인 부에 대해 북한 주민들이 점점 더 알게 되면서 북한에도 물질적 풍요가 있다는 것을 보여주고자 하는 것일수도 있다. 한국의 드라마, 케이-팝 음악은 DVD 와 플래시 드라이브를 통해 점점 더 많이 북한에 유입되고 있으며 이는 지금까지 폐쇄되었던 북한 주민들의 정신적 문화적 사고를 파고 들면서 북한 정권에 잠재적 위협이 되고 있다. 탈북자 태영호가 최근 미 의회에서 증언하였듯이, 북한밖의 세상에 대한 정보의 접근이 진정한 영향을 미치기 시작한 것이다: “겉으로는 김정은 정권이 공포 정치를 통하여 권력을 공고히 한 듯이 보이지만… 북한 내부에는 크고 예상치 않았던 변화가 일어나고 있다.”

물론 김정은은 엄청난 권력을 가지고 있고 그의아버지와 할아버지처럼 극도의 잔임함으로 권력을 유지하려 한다. 그는 숙청과 처형으로 통제력을 유지하며 처벌과 보복행위를 즐기고 있는 듯 하다. 김정은이 정권을 장악한지 6년만에 수많은 고위 관리들을 숙청하고 강등시키고 “재교육시키고,” 재배치하였다.

물론 2013년에는 엄청나게 충격적이었던 사건으로 고모부 장성택을 “개만도 못한 추악한 인간쓰레기”라고 부르며 공개적으로 고사총으로 처형하였는데 이는 “당의 유일적령도”를 훼손하고 “반당, 반혁명적 분파행위”를 한 것이 이유였다. 김정은은 아마도 자신의 이복형이자 북한의 최고지도자 자리의 경쟁자라고도 볼 수 있는 김정남을 치명적인 화학무기제인 VX 신경작용제로 공격하라는 명령을 내렸을 가능성이 크다. 말레이지아 공항 카메라에 찍힌 김정남의 끔찍한 죽음의 영상은 전세계로 퍼졌었다.

김정은은 자신을 거역하는 그 누구도 가만두지 않는다는 것을 분명히 하였다. 김정은의 공포와 억압의 정치가 – 파스텔톤의 아름다운 워터파크를 배경으로 한 – 의미하는 것은 두렵고 억압받는 북한 주민들은 앞으로도 김정은의 환상과 기대, 자신과 북한의 운명에 대한 크고 허왕된 비젼을 통하여 계속 보게 될 것이라는 사실이다.

더 크게, 나쁘게, 더 대담하게

지난 6년간 김정은은 자신의 행동에 대한 국제사회의 인내심을 찔러도 보고 시험해보면서 경계선을 확대하고 있고 그 어떠한 처벌도 이겨낼 수 있다고 계산하고 있다. 사실 상당 부문에서 그는 한반도의 주도권을 유지하고 있으며 이는 미국과 주변국들을 좌절하게 한다. 미국과 국제사회가 더욱 강경한 제재조치를 가하는 와중에 김정은은 재정적 댓가와 심화되는 국제적 고립에도 불구하고 핵무기 개발에 한층 더 박차를 가하고 있다.

북한이 2012년 2월 소위 식량지원 댓가로 북한의 핵과 탄도미사일 실험중지를 합의를 한 지 겨우 2주 만에, 새로 등장한 김정은 정권은 제재조치에 금지되어 있는 탄도미사일 기술을 이용한 우주선 발사 계획을 발표하였다. 우주선 발사는 실패로 끝났으나 북한은 4월 실험 이후의 국제적인 비난에도 불구하고 그 다음 시도인 2012년 12월에 위성을 궤도에 진입시키는데 성공하였다. 김정은이 직접 위성통제소에서 로켓 발사를 명령하는 것을 보여주면서 북한 국영매체는 새로운 지도자 김정은을 국제적 제재에도 불구하고 대담하게 행동하는 지도자로 보여주었다. 두 달 뒤인 2013년 2월, 김정은 통치 약 1년후, 북한의 제3차 핵실험이자 김정은의 첫 핵실험이 시행되었다.

김정은하에서 북한은 핵과 미사일 개발에 속도를 내었고 핵보유국이라는 명칭을 2012년 개정헌법에 기재함으로써 핵보유국이라는 위치를 공식화 하였다. 또한 핵능력 발전에 대한 김정은의 역할을 재확인함으로써 핵사용에 대한 그의 권한을 강화하였다. 김정은은 지금까지 약 세 차례의 추가 핵실험을 관장하였으며 잠수함발사 탄도미사일을 포함한 다양한 사거리의 새로운 탄도미사일을 여러 위치에서 시험하였고 2017년 7월과 11월에는 대륙간 탄도미사일을 시험발사하였다.

북한은 미국과 동맹국들을 위협할 수 있는 능력을 빠르게 강화하고 있음을 보여주는 동시에 분쟁발발시 생존을 위한 2차타격능력을 개발하고 있다. 하지만 북한은 2013년 자위적 핵보유국의 지위를 공고히 하는 법에도 주창하듯이 핵무기는 억제를 위한 것이라고 계속 주장해왔다. 2017년 9월 유엔총회에서 북한 외무상의 발언을 포함한 그 후의 발표들을 보면 북한은 같은 맥락의 주장을 해 왔다. “(북한의) 국가 핵능력은 그 무엇보다 미국의 핵위협과 군사적 침략을 막기위한 전쟁 억제가 목적이다.” 그는 또한 북한의 궁국적 목표는 “미국과의 힘의 균형을 수립하는 것”이라고 하였다.

김정은이 발전된 핵무기능력을 과시하는 동시에 그는 또한 북한의 도발수단을 다양화하여 사이버공격, 생화학물 무기 사용과 세계에서 가장 큰 육군병력의 하나인 백만명 전사를 육군으로 가진 북한군을 현대화하고 있다. 김정은은 중요한 포병 화력 시범 현장을 직접 감독하고, 미국과 한국을 공격하는 군사작전을 자세히 들여다보는 사진도 보이며, 미국과 국제사회의 압력에 대한 대응으로 선동적인 위협을 발표하기도 했다.

이 중에는 대중문화에서 북한을 부정적으로 표현하는 자들에 대한 위협적인 발언도 있다. 예를 들면 2014년 북한은 만일 김정은이 암살당하는 내용을 담은 코메디 영화 “인터뷰”가 출시될 경우, 이를 “전쟁행위”로 간주할 것이라고 위협하였다; 또 북한의 해커들은 영화를 상영하는 영화관에 대해 9/11 과 같은 공격이 있을 것이라고 위협했다.

9/11 과 같은 사건은 일어나지 않았지만, 북한 정권은 사이버공격을 통하여 김정은과 북한을 모욕하는 것은 좌시하지 않을 것이며 엄청난 재정적 댓가를 치를 것이라는 것을 보여주었다. 북한 해커들은 이 영화를 제작한 소니 픽쳐 엔터테인먼트의 데이터를 파괴하였고 회사의 비밀정보인 월급 리스트, 직원 약 5만명의 사회보장번호, 그리고 아직 개봉되지 않은 영화 다섯 편을 공개 사이트에 올렸다.

이렇게 대담하고 나쁜 행동을 보여주고 있음에도 불구하고 김정은이 미국과의 군사적 대결을 원하고 있는 것은 아니다. 그는 이성적이고, 자멸적이지 않으며, 북한의 군사능력이 상당한 약점을 가지고 있다는 것을 거의 확실히 알고 있기에, 북한이 한국이나 미국과의 장기적인 분쟁은 견디지 못한다는 것을 잘 알고 있을 것이다. 김정은이 공격적이기는 하나 무모하거나 “미친 사람”은 아니다. 그는 사실 어떻게 또 언제 재계측 하는지를 배우고 있다. 그의 재계측하고 노선을 바꾸고 전술을 조정하는 능력이야말로 “우리의 사고방식의 약점과 편견” 에 대한 호이어의 경고에 귀를 기울여야 하는 이유이며 북한을 분석하는데 있어서 “기대 패턴” 가정이나 인식에 계속 질문을 던져야 하는 것이다. 우리는 김정은에게 영향을 미치는 새로운 정보를 어떻게 통합할 것인지를 배우고 심각하고 계속 변화하는 이 국가안보적 위협에 어떻게 대응할지 배워야 한다.

2011년 이후 김정은이 더 대담해진 것은 사실이다. 그는 실로 많은 짓을 했다: 여러번의 미사일 시험 발사, 핵실험, 말레이시아에서 VX 로 의심되는 신경제로 의복형 살해, 2015년 비무장지대 지뢰사건, 영화 “인터뷰” 출시 대응으로 소니사의 전세계망의 반을 지워버린 것, 북한에 대한 적대적 행위 혐의로 구금되어15년 강제노동을 선고받은 오토 웜비어 학생의 학대와 사망. 그러나 김정은은 조심스럽게 미국 또는 연합군의 군사대응을 유발하여 정권에 위협이 될 만한 행동은 하지 않았다.

하지만 그는 군사적 위협이나 대화 접근에도 불구하고 핵무기를 포기하지 않을 것이라는 주장은 확실히 해왔다. 핵프로그램을 자신의 정권의 안위와 북한 지도자의 정통성에 필수라고 생각하는 것이 분명하다. 일반적인 핵군축을 했을 시의 결과에 대해 매우 실질적인 공포심을 느끼고 있을 수 있다.

북한은 핵무기를 포기했을 때 어떤 일이 일어나는지의 예로 이라크와 리비아를 – 침공과 지도자 제거 – 자주 언급하였다. 2017년 아스펜 안보포럼에서 미국가정보국장인 댄 코츠는 김정은이 “핵능력이 있는 국가들이 가진 영향력과 세계에서 어떤 일이 일어나고 있는지를… 보아왔다”면서 북한이 리비아에서 얻은 “교훈”은“핵이 있으면, 절대 포기하지 마라. 핵이 없으면, 가져라”라고 한다.

이 나라들과의 비교를 더 분석해보면, 김정은이 리비아의 지도자 무아마르 알 카다피의 죽음에 얼마나 충격을 받았을지 상상할 수 있다. 한 때 “아프리카의 왕”이며 리비아를 사십년동안 통치했던 카다피는 2011년 10월, 김정은이 지도자로 양성되고 있고 김정일이 죽기 두 달전 즈음, 반란군에게 체포되었다. 피로 범벅된 카다피의 영상은 전세계로 전파되었다. 또 카다피가 체포되어 벌거벗은 채로 군중들에게 맞고 폭행당한 뒤에 시체가 냉동고에 저장되었다고 뉴스에 보도되었다.

북한 지도자라는 새로운 역할을 받아들이고 있는 김정은에 있어서 아마 이 영상은 그의 뇌리에 깊게 새겨졌을 것이다. 북한이 핵을 포기하면 밝은 미래가 있을 것이라는 미국의 약속은 북한 정권에게는 허황된 것으로 보일 터였다. 당시 북한 외무성에 따르면, 리비아 사태는 미국이 주도하여 리비아를 꾀여서 대량살상무기를 포기하도록 한 것으로써 “국가를 무장해제 하기 위한 침공 전략이었다.”

뿐만 아니라 카다피의 죽음은 당시 소위 아랍의 봄 시기에 일어난 것으로 권위주의적 정권에 대하여 민중봉기가 중동과 북아프리카를 휩쓸던 2010년과 2011년이었다. 그 때까지 천하무적이던 정권이 무너지는 것을 보면서 김정은은 약해 보이는 것의 결과를 보았고, 따라서 반대의견을 잔인하게 억압하는 김 왕조의 관행을 더욱 더 강화하였다.

이러한 경고 사건들이 없었다고 하더라도 김정은이 비핵화를 심각하게 고려했을 가능성은 크지 않다. 핵이 있는 북한에서 성년이 된 김정은과 그의 세대에게, 핵을 해제한다는 것은 비현실적인 개념이고 계산상 전혀 득볼게 없는 옛날 “현대-이전의” 시대로 돌아가는 것일뿐 아니라, 트럼프 행정부가 “예방적 전쟁”을 암시하고 대통령이 트위터로 김정은에 대하여 “화염과 분노” 를 얘기하고 이미 준비태세와 장전이 완료된 군사적 옵션을 위협하는 상황에서는 더욱 더 핵해제의 가능성은 없어 보인다.

자만심

2017년 여름과 가을, 북한의 매우 도발적인 행동들은 – ICBM 시현, 열원자 장치 시험, 태평양 위에서 수소폭탄 폭발 위협등 – 김정은의 자신감이 지난 6년간 꾸준히 커지고 있음을 시사한다. 사실 그는 한국의 박근혜 대통령과 바락 오바마 대통령보다 더 오래 집권하고 있다. 어쩌면 그는 도날드 트럼프 대통령과 중국의 시진핑 수석도 위협과 책략으로 이길 수 있을 것으로 생각하는지 모른다.

이러한 자신감은 김정은이 아버지나 할아버지와는 달리 지금까지 진정한 “위기”를 겪어보지 못했기 때문에 더욱 심할 수도 있다. 그는 지금까지 군사적 힘의 과시와 도발적인 행동을 통하여 목적을 달성하였을 뿐 협상이나 타협, 외교의 기술에는 전혀 경험이 없다.

김정은의 초점은 핵무기 프로그램과 재래식 능력 강화이며 2011년 이후 북한의 외교관들은 옆으로 밀려나 있다. 또 최근에는 트럼프 대통령과의 말싸움을 즐기고 있는듯 한데 트럼프 대통령이 트위터와 9월 유엔총회 연설을 통해 자신을 공격한 후 김정은은 트럼프 대통령을 “미치광이”라고 불렀다. 더불어 내부에 잇따른 숙청이 이어지는 상황에서 북한 관리중에 김정은에게 미국이나 중국과의 대화 또는 유화정책을 권하는 사람이 있다면 그는 매우 용감한 사람일 것이다. 김정은은 억압과 충성하는 자들에게 경제적인 혜택과 특혜를 제공하기에 아첨꾼이 되기 십상이고 이는 또 그가 폭력과 공격성을 더 선호하게 만든다.

그러나 이제 그도 전략적 선택을 해야 하는 임계점에 도달했을 수 있다. 김정은이 열렬히 핵무기를 추구하는 것은 사실이나 그는 자신이 공개한 병진노선 정책을 통한 북한 경제 개선에도 집중해야 한다. 많은 국내 변화와 강한 제재조치, 또 그 어느 때보다 강하게 압박하는 중국등을 감안할 때 결코 쉽지 않은 과제이다. 또 외부세계에서 더 많은 정보가 유입되고 자원과 시장에 대한 국가의 통제 완화, 소비주의 부상, 부유 계층 성장등의 국내 환경의 변화는 김 정권에 심각한 스트레스를 주는 것이다.

그와 동시에 북한에 대한 국제적 압력은 그 어느 때보다 강하다. 최근의 몇 가지 조치들은 북한의 경화 획득 능력을 약화시켜 정권의 경제적 군사적 목표달성에 필요한 자금줄을 죄고 있다. 이 조치들은 11월 북한의 ICBM 시험후 최근 채택된 유엔안보리결의안 2397호와 미국의 성공적인 노력으로 중국을 포함한 국제사회가 북한과의 무역과 금융관계를 단절한 조치들, 그리고 2017년 9월 21일 트럼프 대통령 행정명령으로 북한에 대한 새로운 제재조치 통과 및 광범위한 제3자 제재조치 단행등이다. 이러한 것들은 김정은이 엘리트층을 보상해줄 수 있는 능력을 제한시키고 엘리트층도 자신들을 위한 또는 정권에 갖다바칠 충성자금을 조성하기 힘들게 한다.

이 모든 대내외적 압력들의 무게가 북한 내부의 기대치가 높아지는 시점에 한꺼번에 덮치면서 북한 정권을 압도할 수도 있다 – 김정은이 공격성을 줄이는 법을 배운다면 상황이 달라지겠지만 물론 이것은 매우 큰 가정이다.

우리는 김정은의 오만함을 걱정해야 한다. 2012년 김정은은 첫 대중연설의 마무리를 이렇게 했다 “최후의 승리를 향하여 앞으로.” 물론 그 연설은 전세계가 본 중에 가장 대단한 북한 무기들의 행진을 뒷배경으로 한 연설이었으나, 내 귀에는 이 말이 젊은 지도자의 엄포처럼 들렸다. 그가 자신의 입장을 보여주는 것이었을 수도 있으나 최근의 진척상황과 통제권을 가졌다는 김정은의 더 커진 자신감을 볼 때 미국과 동맹국, 중국 모두 김정은이 현재 주장하고 있는 방어적인 태세가 아닌 더 큰 욕망을 충족시키기 위한 것으로 바뀔 가능성을 주시해야 한다.

나는 아직도 2017년 미정보국장이 증언했던 미정보당국의 평가인 “북한의 핵능력은 억제, 국제적 영예 그리고 강압적인 외교를 위한 것”이라는 평가에 동의한다. 하지만 김정은의 미래의 의도를 과거의 발언과 행동을 기반으로 추정하는 것은 잘못이라고 본다. 왜냐하면 우리는 결코 확신을 가지고 김정은을 이해할만큼 북한의 의도와 능력에 대한 정보를 가지고 있지 않으며 또 앞으로도 가질수 없을 것이기 때문이다. 김정은과 북한은 변화하지않고 고정된 그러한 반역사적인 공간에 존재하는 것이 아니다. 우리의 분석과 정책 대응도 함께 변화하고 진화되며 모든 가능한 시나리오에 대하여 준비돼 있어야 한다. 우리 자신도 오만함을 피해야 할 것이다.

우리가 북한의 발표, 국영방송의 내용, 인프라의 위성사진과 정부제작 영상, 탈북자들의 증언을 일일이 파헤치면서 분석하고 있지만 동시에 우리가 기억할 것은 우리가 그를 보고 있듯이 김정은도 우리를 보고 있다는 사실이다. 미국은 북한의 핵프로그램의 위협을 최소화하기 위해 노력을 하되 의도하지 않은 무력분쟁을 야기할 수 있는 조건을 만들어서는 안된다. 미국은 김정은의 계산을 바꾸고, 그의 야심을 억제시키고, 강화되고 있는 국제적인 압력을 과연 자신이 감당할 수 있을까에 대한 김정은의 생각을 바꿀수 있는 기회가 있다.

내가 다른 글에서도 주장했듯이, 우리는 아직 김정은이 다른 길을 선택하고 비핵화로 나아갈 조치로 눈을 돌릴 의사가 있는지를 시험해 볼 수 있다. 이는 북한 문제에 대해서 한 치의 이견이 없는 지역 동맹 강화를 – 특히 한국과 일본 – 통해서 할 수 있다. 우리는 또 핵프로그램의 자금줄을 차단하고 북한 주민에게 번영을 가져다 주겠다는 김정은의 약속을 약화시킴으로 북한 정권에 대한 압력을 강화하고, 방어 및 사이버능력을 강화시켜 미국과 동맹국을 위협하는 북한에 대처해야 한다. 또한 북한으로의 외부세계에 대한 정보 침투를 확대하고 북한의 인권침해에 대한 인지도를 높이는 동시에 김씨 정권 이후의 시대에 대한 신뢰성있는 대안을 보여줌으로써 탈북을 독려하는 등 북한 정권에 대한 압박을 더욱 가중시켜야 한다.

김정은은 아직 배우는 중이다. 우리는 그가 올바른 것들을 배우도록 해야 한다.

Jung H. Pak 은 브루킹스 연구소 동아시아정책연구센터의 SK- 한국국제교류재단 한국학 석좌이자 선임연구원이다. 북한의 대량살상무기능력, 북한정권의 국내외 정책분석, 국내 안정, 남북관계를 포함한 미국과 동아시아가 직면하고 있는 국가안보문제를 다루고 있다. 미중앙정보국과 미국가정보장실에서 고위직을 역임하였다. 국가안보관련 연구를 하기 전에는 뉴욕 헌터대학에서 미국역사를 가르쳤으며 풀브라이트 장학생으로 한국을 연구한 바 있다.

-------

THE EDUCATION OFKIM JONG–UNBY JUNG H. PAKFebruary 2018한국어

WHEN NORTH KOREAN STATE MEDIA reported in December 2011 that leader Kim Jong-il had died at the age of 70 of a heart attack from “overwork,” I was a relatively new analyst at the Central Intelligence Agency. Everyone knew that Kim had heart issues—he had suffered a stroke in 2008—and that the day would probably come when his family’s history of heart disease and his smoking, drinking, and partying would catch up with him. His father and founder of the country Kim Il-sung had also died of a heart attack in 1994. Still, the death was jarring.

While North Koreans wept, fainted, and convulsed with grief, feigned or not, Kim Jong-un, the twenty-something-year-old son of Kim Jong-il, reportedly closed the country’s borders and declared a state of emergency. News of these events began to filter out to the international media through cell phones that had been smuggled in before Kim Jong-il’s death.

There had been signs before 2011 that Kim was grooming his son for the succession: he began to accompany his father on publicized inspections of military units, his birth home was designated a historical site, and he began to assume leadership titles and roles in the military, party, and security apparatus, including as a four-star general in 2010.

In response to the death, South Korea convened a National Security Council meeting as the country put its military and civil defense on high alert, Japan set up a crisis management team, and the White House issued a statement saying that it was “in close touch with our allies in South Korea and Japan.” Back in Langley, I remember being watchful for any indications of instability, as I began to develop my thinking on what was happening and where North Korea might be headed under the newly named leader. Immediately after Kim Jong-il’s death was announced, the North Korean state media made it clear that Jong-un was the successor: “At the forefront of our revolution, there is our comrade Kim Jong-un standing as the great successor … ” Pyongyang residents mourn the death of their leader, Kim Jong-il, in December 2011. Reuters/Kyodo

Pyongyang residents mourn the death of their leader, Kim Jong-il, in December 2011. Reuters/Kyodo

What sort of person was Kim Jong-un? Would he even want the burden of being North Korea’s leader? And if so, how would he govern and conduct foreign affairs? What would be his approach to the nuclear weapons program that he inherited? Would the elites accept Kim? Or would there be instability, mass defections, a flood of refugees, bloody purges, a military coup?

Predictions about Kim’s imminent fall, overthrow, or demise were rife among North Korea and Asia watchers. Surely, someone in his mid-20s with no leadership experience would be quickly overwhelmed and usurped by his elders. There was no way North Koreans would stand for a second dynastic succession, unheard of in communism, not to mention that his youth was a critical demerit in a society that prizes the wisdom that comes with age and maturity. And if Kim Jong-un were to hold onto his position, what would happen to his country? North Korea was poor and backward, isolated, unable to feed its people, while clinging to its nuclear and missile programs for legitimacy and prestige. Under Kim Jong-un, the collapse of North Korea seemed more likely than ever.

That was then.

In the six years since, Kim has collected a number of honorifics, cementing his position as North Korea’s leader. Kim has carried out four of North Korea’s six nuclear tests, including the biggest one, in September 2017, with an estimated yield between 100-150 kilotons (the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan during World War II was an estimated 15 kilotons). He has also tested nearly 90 ballistic missiles, three times more than his father and grandfather combined. North Korea now has between 20 and 60 nuclear weapons and has demonstrated ICBMs that appear to be capable of hitting the continental United States. It could also be on track to have up to 100 nuclear weapons and a variety of missiles—long-range, road-mobile, and submarine-launched—that could be operational as early as 2020. Under Kim, North Korea has conducted major cyberattacks and reportedly used a chemical nerve agent to kill Kim’s half-brother at an international airport.

The last six years have also seen Kim dotting the North Korean landscape with ski resorts, water parks, and high-end restaurants to showcase the country’s modernity and prosperity to internal and external audiences. They are also meant to deliver on his promise to improve the people’s lives—as part of his byungjin policy of developing both the economy and nuclear weapons capabilities—and to attract foreign tourists.

Yet even as he is modernizing his country at a furious pace, Kim has deepened North Korea’s isolation. Having rebuffed U.S., South Korean, and Chinese attempts to reengage, he has refused to meet with any foreign head of state, and so far as is known, since becoming leader his significant foreign contacts have been limited to Kenji Fujimoto, a Japanese sushi chef whom he knew in his youth and whom he invited to Pyongyang in 2012, and Dennis Rodman, an American basketball player, who has visited North Korea five times since 2013.

Kim Jong-un is here to stay.

Of Missiles and Men

The pace of weapons testing is speeding up. Kim Jong-un has already tested nearly three times more missiles than his father and grandfather combined. Source: James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies/Nuclear Threat Initiative

Source: James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies/Nuclear Threat Initiative

A painting of the late North Korean leaders Kim Il-sung (L) and Kim Jong-il hints at the opaqueness of the Hermit Kingdom. Jason Lee/Reuters

THE TEN-FOOT-TALL BABY

North Korea is what we at the CIA called “the hardest of the hard targets.” A former CIA analyst once said that trying to understand North Korea is like working on a “jigsaw puzzle when you have a mere handful of pieces and your opponent is purposely throwing pieces from other puzzles into the box.” The North Korean regime’s opaqueness, self-imposed isolation, robust counterintelligence practices, and culture of fear and paranoia provided at best fragmentary information.

Intelligence analysis is difficult, and not intuitive. The analyst has to be comfortable with ambiguity and contradictions, constantly training her mind to question assumptions, consider alternative hypotheses and scenarios, and make the call in the absence of sufficient information, often in high-stakes situations. To cultivate these habits of mind, we were required to take courses to improve our thinking. Walk into any current or former CIA analyst’s office, and you will find a slim, purple book by Richards Heuer with the title Psychology of Intelligence Analysis. This is required reading for CIA analysts. It was presented to us during our initial education as new CIA officers and often referred to in subsequent training. It still sits on my shelf at Brookings, within arm’s reach. When I happen to glance at the purple book, I am reminded about how humility is inherent in intelligence analysis—especially in studying a target like North Korea—since it forces me to confront my doubts, remind myself about how I know what I know and what I don’t know, confront my confidence level in my assessments, and evaluate how those unknowns might change my perspective. Anita Kunz/The New Yorker

Anita Kunz/The New Yorker

Heuer, who worked at the CIA for 45 years in both operations and analysis, focused his book on how intelligence analysts can overcome, or at least recognize and manage, the weaknesses and biases in our thinking processes. One of his key points was that we tend to perceive what we expect to perceive, and that “patterns of expectations tell analysts, subconsciously, what to look for, what is important, and how to interpret what is seen.” The analyst’s established mindset predisposes her to think in certain ways and affects the way she incorporates new information.

What, then, are the expectations and perceptions that we need to overcome to form an accurate assessment of Kim Jong-un and his regime? Given the over-the-top rhetoric from North Korea’s state media, Kim’s own often outrageous statements, and the hyperbolic imagery and boastful platitudes perpetuated by the ubiquitous socialist realism art, it has been only too easy to reduce Kim to caricature. That is a mistake.

When the focus is on Kim’s appearance, there’s a tendency to portray him as a cartoon figure, ridiculing his weight and youth. Kim has been called—and not just by our president—“Rocket Man,” “short and fat,” “a crazy fat boy,” and “Pyongyang’s pig boy.” A New Yorker cover from January 18, 2016, soon after North Korea’s fourth nuclear test, portrayed him as a chubby baby, playing with his “toys”: nuclear weapons, ballistic missiles, and tanks. The imagery suggests that, like a child, he is prone to tantrums and erratic behavior, unable to make rational choices, and liable to get himself and others into trouble.

However, when the focus is on the frighteningly rapid pace and advancement of North Korea’s cyber, nuclear, and conventional capabilities, Kim is portrayed as a ten-foot-tall giant with untold and unlimited power: unstoppable, undeterrable, omnipotent.

The coexistence of these two sets of overlapping perceptions—the ten-foot-tall baby—has shaped our understanding and misunderstanding of Kim and North Korea. It simultaneously underestimates and overestimates Kim’s capabilities, conflates his capabilities with his intentions, questions his rationality, or assumes his possession of a strategic purpose and the means to achieve his goals. These assumptions distort and skew our policy discussions.

A woman in Pyongyang walks past a billboard advertising North Korea’s missile prowess. The capital city is rife with stylized propaganda. David Guttenfelder/National Geographic Creative

FOOTSTEPS OF GENERAL KIM

If he had followed Korean custom and tradition, Kim Jong-il would have named Kim Jong-nam, not Kim Jong-un, his successor, because Jong-nam was the eldest of his three sons. But Kim Jong-il reportedly rejected Jong-nam as being unfit to lead North Korea. Why? For one, the elder Kim might have judged that Jong-nam was tainted by foreign influence. In 2001 Jong-nam had been detained in Japan with a fake passport in a failed attempt to go to Tokyo Disneyland. More seriously, it is said that he had suggested that North Korea undertake policy reform and open up to the West, enraging his father.

The second son, Jong-chul, was deemed too effeminate; one of Jong-chul’s friends recalled that “[Jong–chul] is not the type of guy who would do something to harm others. He is a nice guy who could never be a villain.” Indeed, he seems to be playing an unspecified supporting role in his younger brother’s regime.

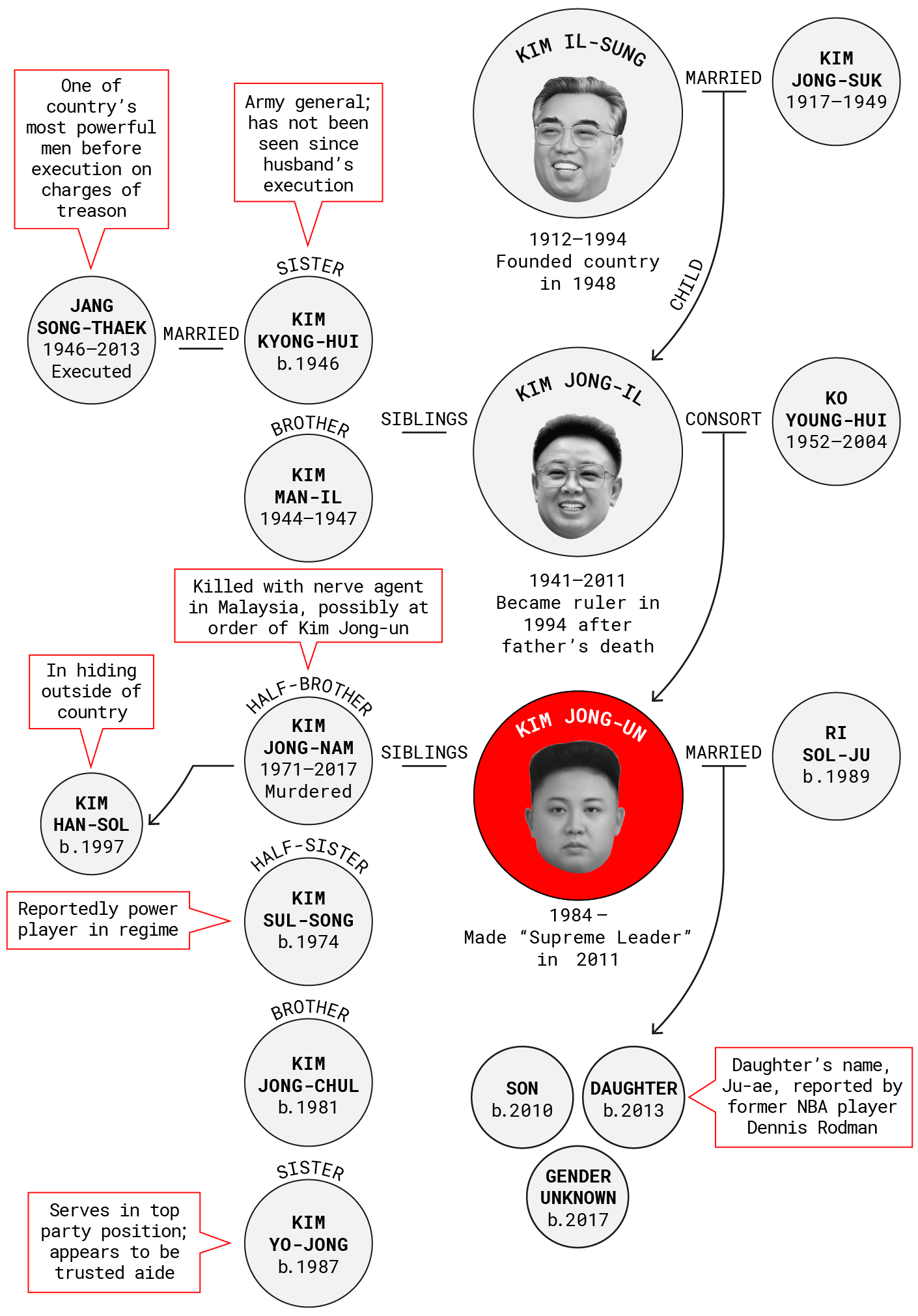

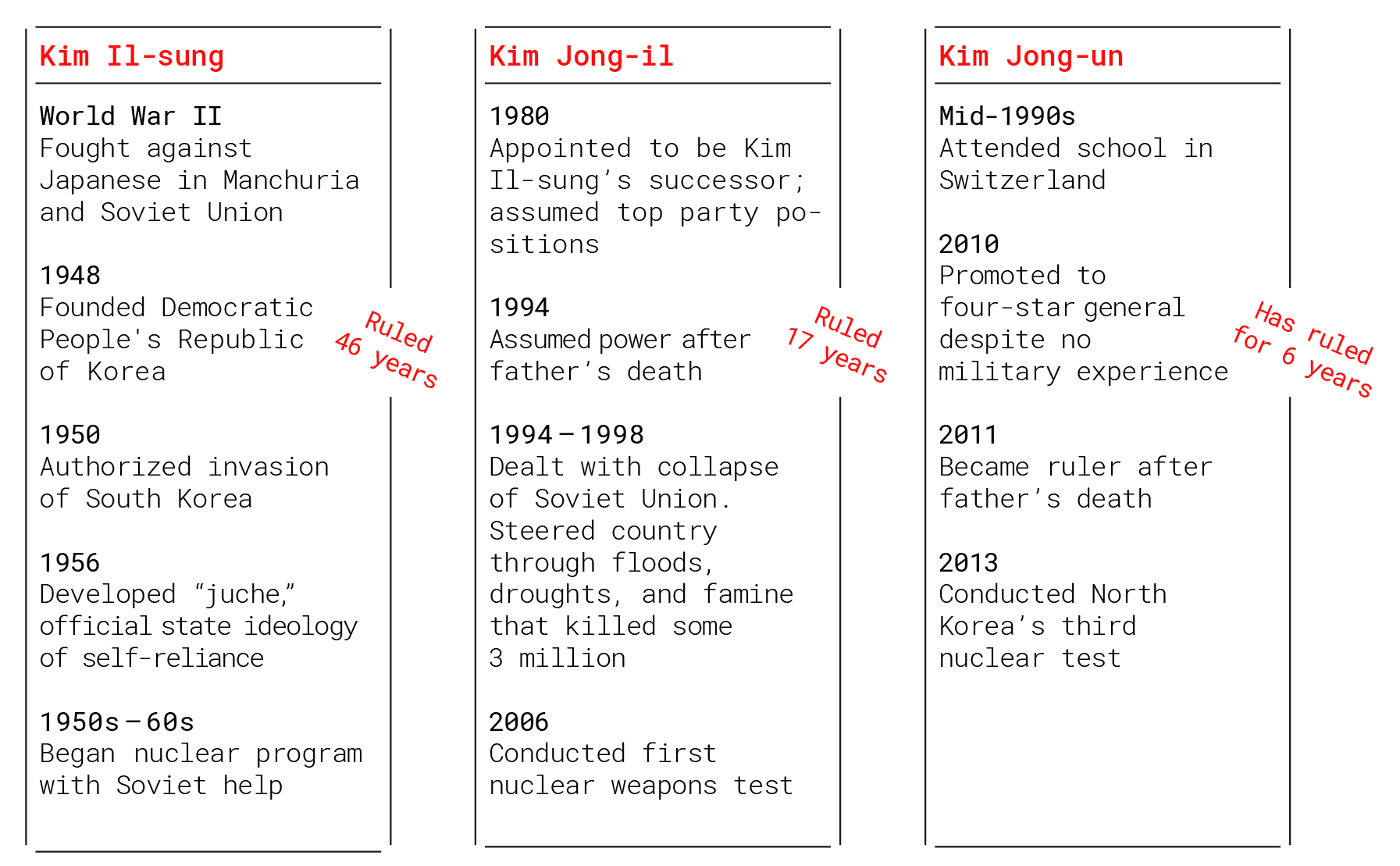

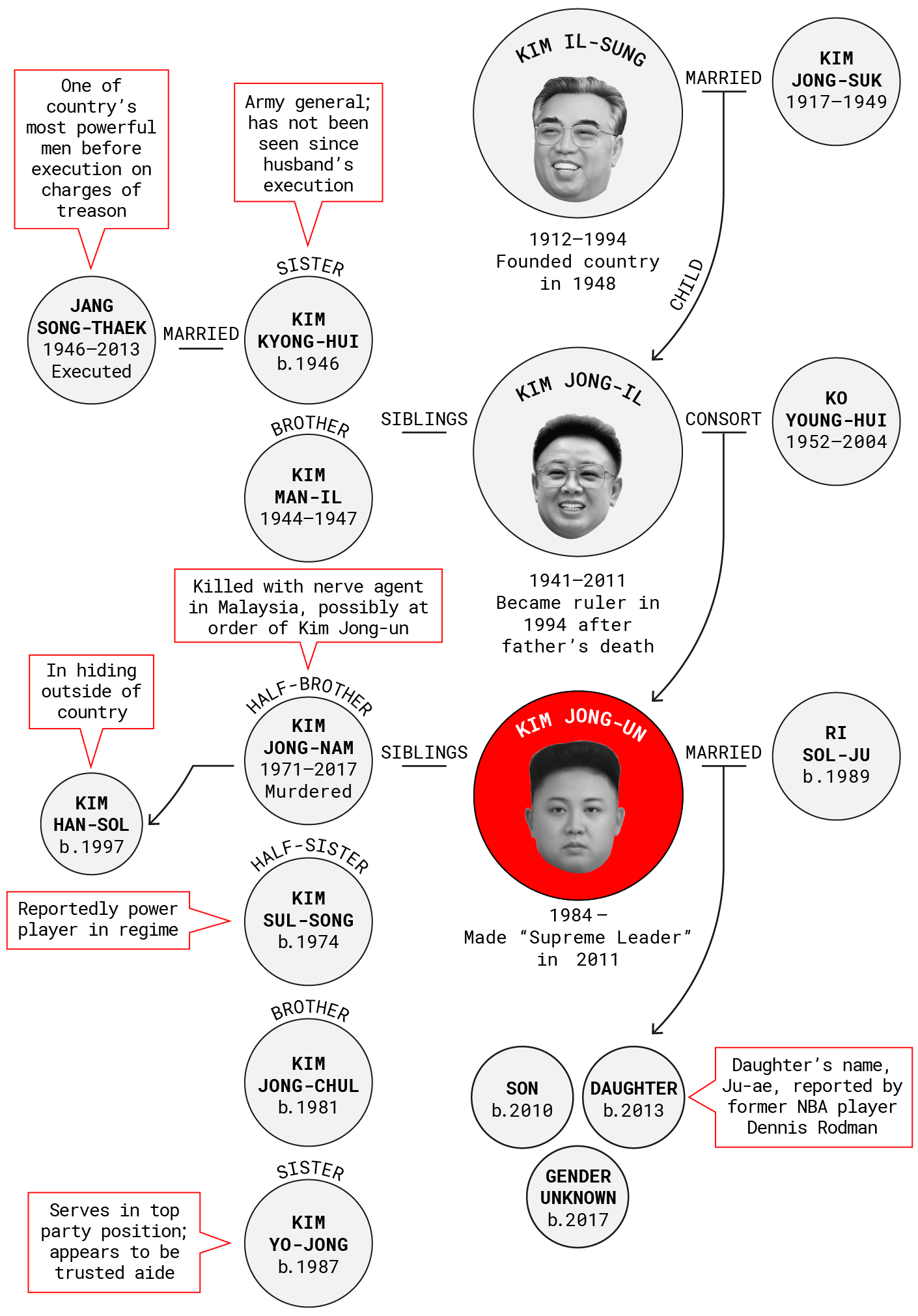

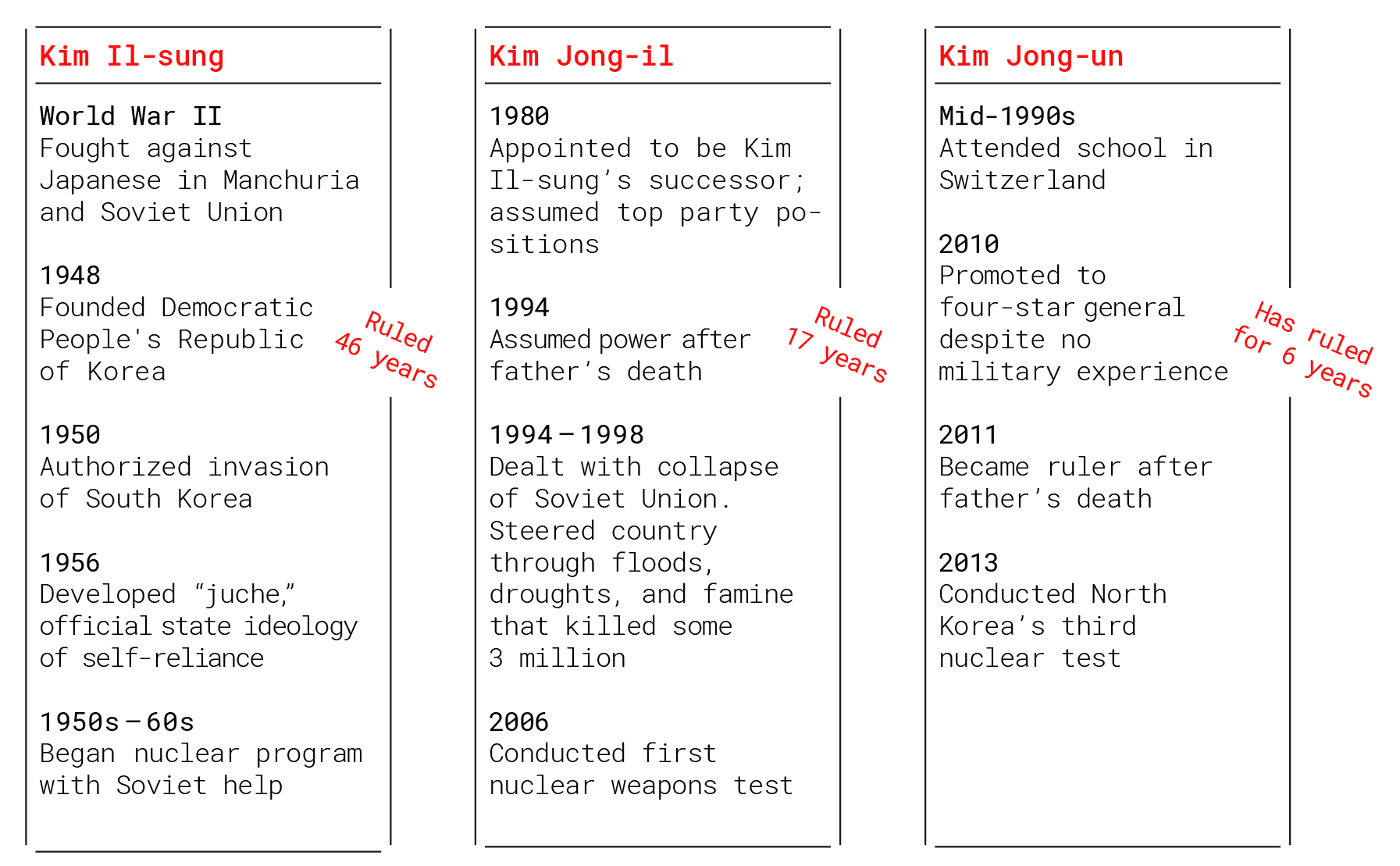

All in the family

Four generations of Kims: A selective history* *North Korea’s secrecy makes it difficult to verify information about Kim Jong-un’s children, including how many there are and when they were born. His wife’s birth date is also unconfirmed.

*North Korea’s secrecy makes it difficult to verify information about Kim Jong-un’s children, including how many there are and when they were born. His wife’s birth date is also unconfirmed.

That left Jong-un, whom the elder Kim chose to be the third Kim to lead North Korea because he was the most aggressive of his children. Kenji Fujimoto, Kim Jong-il’s former sushi chef, who visited Pyongyang at the request of Kim Jong-un, has provided some of the most fascinating firsthand observations about Jong-un and his relationship with his father. Fujimoto claims that Jong-il had chosen his youngest son to succeed him as early as 1992, citing as evidence the scene at Jong-un’s ninth birthday banquet where Jong-il instructed the band to play “Footsteps” and dedicated the song to his son: Tramp, tramp, tramp; The footsteps of our General Kim; Spreading the spirit of February [a reference to Kim Jong-il, who was born in February]; We, the people, march forward to a bright future. Judging from the lyrics, Jong-il was expecting Kim Jong-un to lead North Korea into the future, guided by the spirit and legacy of his father.

Though Jong-il saw in his son a worthy successor to the dynasty, there are critical differences between the first two Kims and Kim Jong-un. Kim Il-sung, the country’s founder and Jong-un’s grandfather who ruled for nearly five decades until his death in 1994, was a revolutionary hero who fought Japanese imperialism, the South Korean “puppets,” and the American “jackals” in a military conflict that ended only because of an armistice.

In the next generation Kim Jong-il had to navigate through world-changing events that included the collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent end of large-scale aid from Moscow, a changing relationship with the ever-suspicious Chinese who seemed to be prioritizing links with Seoul, and tense negotiations with the United States on North Korea’s burgeoning nuclear program. And let’s not forget the famine and the drought of the 1990s, or the tightening noose of sanctions and international ostracism.

In contrast with his battle-hardened elders, Kim Jong-un grew up in a cocoon of indulgence and privilege.

1990sChicago Bulls

Kim Jong-un has a well-known love of basketball. According to a GQ interview, it began when a Japanese contact sent him VHS tapes of Chicago Bulls‘ playoff games.

During the 1990s famine, in which as many as 2–3 million North Koreans died as a result of starvation and hunger-related illnesses, Kim was in Switzerland. His childhood was marked by luxury and leisure: vast estates with horses, swimming pools, bowling alleys, summers at the family’s private resort, luxury vehicles adapted so that he could drive when he was 7 years old. For Kim, skiing in the Swiss Alps and swimming in the French Riviera must have seemed part of his birthright. Kim had a temper, hated to lose, and loved Hollywood movies and basketball player Michael Jordan.

Fujimoto, the sushi chef, has described Jong-un’s mother as not very strict about education and says that he was never forced to study. His friend and classmate in Switzerland said of Kim: “We weren’t the dimmest kids in the class but neither were we the cleverest. We were always in the second tier … The teachers would see him struggling ashamedly and then move on. They left him in peace.” Jong-un was apparently unbothered by his less-than stellar scores; as his classmate noted, “He left without getting any exam results at all. He was much more interested in football and basketball than lessons.”

Despite his apparent lack of seriousness, Jong-un seems to have known from early on that, as his father’s chosen successor, he was destined to lead. His strong self-esteem and confidence were cultivated beginning when he was very young. And the Kim family dynasty—a totalitarian regime—carefully created a cult of personality around the young boy, as it had done with his father and grandfather before him, reinforcing it through fear and intimidation and shows of force. Kim’s aunt said that at his eighth birthday party, he wore a general’s uniform with stars, and the real generals with real stars bowed to him and paid their respects to the boy. According to Fujimoto, Kim carried a Colt .45 pistol when he was 11 years old and dressed in miniature army uniforms. A young Kim Jong-un (seen here with his mother, Ko Young-hui) is said to have started driving at 7 and begun carrying a pistol at 11. Newscom

A young Kim Jong-un (seen here with his mother, Ko Young-hui) is said to have started driving at 7 and begun carrying a pistol at 11. Newscom

As Mark Bowden wrote in a 2015 Vanity Fair profile, “At age five, we are all the center of the universe. Everything—our parents, family, home, neighborhood, school, country—revolves around us. For most people, what follows is a long process of dethronement, as His Majesty the Child confronts the ever more obvious and humbling truth. Not so for Kim. His world at age 5 has turned out to be his world at age 30 … Everyone does exist to serve him.”

So, while small armies of teachers, tutors, cooks, assigned playmates, bodyguards, relatives, and chauffeurs developed Kim’s sense of entitlement and shielded him from the realities of North Korea and the world beyond when he was a child, the concept of juche (self-reliance) and suryong (Supreme Leader) would provide the ideological and existential justification for his rule when it came time for him to assume the mantle of leadership. The regime’s propaganda machine constructed and promoted the mythology, extolling his wisdom, his martial prowess, and his near supernatural capabilities, an example of which was his supposed ability to drive at age three.

In October 2006, when Kim Jong-un was in his early twenties and two months away from his graduation from Kim Il-Sung Military University (which he had reportedly attended since 2002), North Korea conducted its first nuclear test, providing the Kim dynasty with yet another layer of protection, further steeping the nation in the Kim family mythology of supreme power, and further warping the young Jong-un’s sense of reality and expectations. That nuclear test, and his grandfather’s and father’s commitment to nuclear weapons, would also, however, narrow his choices once he took power, boxing him into the conviction that the fate of the nation and its 25 million people rested on his carrying forward this legacy. The young Kim and his classmates at the military university—the future military elite—no doubt celebrated that nuclear milestone, which probably also fortified their optimism about their country’s nuclear future and reinforced their belief in their role as the defenders of that future.

The Gulag Peninsula

An estimated 200,000 North Koreans are held in some 30 prison camps across the country. Source: The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea (HRNK)

Source: The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea (HRNK)

Once Kim did become the leader, and as such the personification of North Korea’s national interest, he was endowed with all the tools of political repression that had consolidated his father’s and grandfather’s supremacy. These tools allowed him to validate his persecution of any real or suspected dissenters, and to maintain a horrific network of prison camps in which torture, rape, beatings, and a variety of other human rights violations continue to take place to this day, as they have done for many decades. As the U.N. Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea concluded in 2014, North Korea has committed “systematic, widespread and gross human rights violations,” and under its banner of “Kimilsungism-Kimjongilism,” the regime “seeks to dominate every aspect of its citizens’ lives and terrorizes them from within.”

A North Korean soldier in Pyongyang stands vigil in Kim Il-sung Square. The markings on the street are for military parades—a hallmark of dictatorships the world over. David Guttenfelder/National Geographic Creative

A 21ST–CENTURY DICTATORSHIP

As a scholar of U.S. history before I became an intelligence analyst, I couldn’t help but think about Andrew Carnegie’s famous statement about the third generation in America as Kim 3.0 took the reins of power in North Korea. “There are but three generations from shirt sleeves to shirt sleeves.” Or in other words, the first generation makes the money, the second generation maintains it, and the third squanders it. Kim Jong-un seems determined to avoid that fate.

Kim has adopted the mantle of the mythical, godlike leadership role that grandfather and country founder Kim Il-sung and his father Kim Jong-il held and continue to hold in their death. But he seems determined to chart his own path. In short, this is not your grandfather’s dictatorship. Kim Jong-un (right) bears an uncanny likeness to his grandfather Kim Il-sung (seen in hat) in both appearance and demeanor. Reuters/Keystone-France

Kim Jong-un (right) bears an uncanny likeness to his grandfather Kim Il-sung (seen in hat) in both appearance and demeanor. Reuters/Keystone-France

Kim is however harnessing the nostalgia for his grandfather’s era, before the 1990s famine and the collapse of the Soviet Union and the resulting termination of aid. With his uncanny likeness to his grandfather in both appearance and demeanor, he has skillfully exploited the country’s adulation of its founder. Just a few months after he became the leader of North Korea, on the 100th anniversary of his grandfather’s birth, Kim delivered his first public address. As he invoked his grandfather’s legacy in the lengthy, 20-minute speech, he also affirmed his father’s “military first” policy, proclaiming that “the days are gone forever when our enemies could blackmail us with nuclear bombs.” Yet even while endorsing his father’s policy, he was making a remarkable departure from his father’s practice, for this was the first time that North Koreans had heard their leader’s voice in a public speech since Kim Il-sung’s days: Kim Jong-il shunned speaking in public during his almost 20 years of rule.

While basking in the nostalgia for his grandfather, Kim Jong-un is also determined to be seen as a “modern” leader of a “modern North Korea.” His charting of his own path can be seen in another departure from his father’s public persona. Kim has allowed himself to seem more transparent and accessible than his father. He appears in public with his pretty and fashionable young wife, Ri Sol-ju (with whom he has at least one child, and possibly three). He hugs, holds hands, and links arms with men, women, and children, seeming comfortable with both young and old. That transparency has been extended to the government. When one of its satellite launches failed in April 2012, the regime admitted the failure publicly, the first time it had ever done so.

During his frequent public appearances, Jong-un can be seen giving guidance at various economic, military, and social and cultural venues, as his father and grandfather did, but he is also shown pulling weeds, riding roller coasters, navigating a tank, and galloping on a horse. He is comfortable with technology in the form of cell phones and laptops, and is also portrayed speaking earnestly with nuclear scientists and overseeing scores of missile tests. Kim Jong–un frequently appears in public with his glamorous wife, Ri Sol–ju, to promote an image of youth, vigor, and dynamism. KCNA/Reuters

Kim Jong–un frequently appears in public with his glamorous wife, Ri Sol–ju, to promote an image of youth, vigor, and dynamism. KCNA/Reuters

Kim appears to want to reinforce the impression that he is young, vigorous, on the move—qualities that he attributes to his country as well. Speaking directly to the people in April 2012 in that first public speech he gave as their leader, he confidently promised that North Koreans would no longer have to tighten their belts. Later he announced his byungjin policy: that North Korea can have both its nuclear weapons and prosperity. Animated by the optimism of one whose privilege made him believe anything was possible, he has prioritized both these issues and personally taken ownership of them—all part of creating and nurturing his brand.

The images that the regime chooses to disseminate and weave into Kim’s hagiography say a lot about how Kim envisions North Korea’s future and his place in it. The carefully curated public appearances of Kim’s wife, Ri Sol-ju, provide the regime with a “softer” side, a thin veneer of style and good humor to mask the brutality, starvation, and deprivation endured by the people, while reports about the existence of possibly multiple children hint at Kim and his wife’s fecundity and the potential for the birth of another male heir to the Kim family dynasty (although I wouldn’t rule out the possibility for Kim to choose a daughter to lead North Korea, given his “modern” tendencies). For the toiling masses as well as for the elite, Ri, the glamorous and devoted wife, is an aspirational figure.

To outside scholars, Ri’s public appearances offer something else—a glimpse of an emerging material and consumer culture, which Kim seems to be actively promoting. Even as tension with the United States went into overdrive after a sixth nuclear test and the launch of numerous ballistic missiles during the summer and fall of 2017, state media showed Kim and his wife touring a North Korean cosmetics factory. He reportedly urged the industry to be “world competitive,” praised the factory for helping women realize their dream of being beautiful, and offered his own comments on the packaging.

In addition to the beauty industry, the vision of economic development that Kim has been promoting includes ski resorts, a riding club, skate parks, amusement parks, a new airport, and a dolphinarium, perhaps because he considers these as markers of a “modern” state. Or in his naiveté he may simply want his people to enjoy the things to which he has had privileged access. (Fujimoto claimed that when Kim was 18, he ruminated to the sushi chef, “We are here, playing basketball, riding horses, riding Jet Skis, having fun together. But what of the lives of the average people?”)

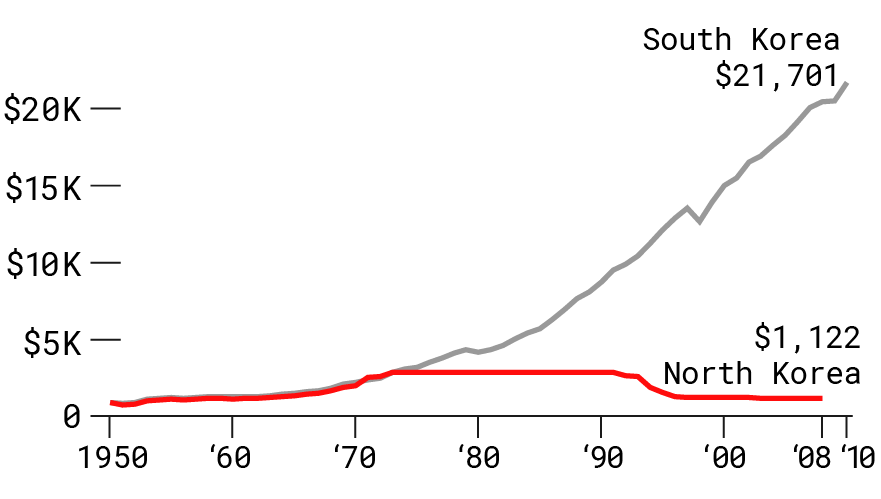

A Tale Of Two Koreas

GDP Per Capita, USD Source: Maddison Project

Source: Maddison Project

Kim may also be using the imagery of these amenities as a corrective, a way of undermining the dominant external narrative of a decaying, starving, economically hobbled North Korea. Perhaps even more importantly, he may be deploying these signs of affluence to craft an internal narrative about North Korea’s material well-being at a time when his people are being exposed to more and more information about South Korea’s wealth. DVDs and flash drives of South Korea’s soap operas and K-pop music have been smuggled into the country in ever greater numbers, infiltrating the previously sealed mental and cultural landscape of North Koreans and presenting a potential danger to the regime. As North Korean defector Thae Yong-ho recently said in testimony to the U.S. Congress, this access to information about how the world outside North Korea lives is beginning to have a real impact: “While on the surface the Kim Jong-un regime seems to have consolidated its power through [a] reign of terror … there are great and unexpected changes taking place within North Korea.”

Of course, Kim still has enormous power and, like his father and grandfather, the willingness to hold onto it through extreme brutality. He maintains control through purges and executions—punishments and acts of revenge he appears to inflict with relish. In the six years of his reign the regime has purged, demoted, “reeducated,” and shuffled scores of senior leaders.

340Executions

Between 2011 and 2016, Kim Jong–un reportedly ordered scores of executions—sometimes for trivial reasons such as half–hearted clapping and sleeping in a meeting.

Source: Institute for National Security Strategy (INSS)

There was also the spectacularly shocking public humiliation of Kim’s uncle Jang Song-thaek in 2013, who was labeled “human scum” and “worse than a dog” and then reportedly executed by an anti-aircraft gun for allegedly undermining the “unitary leadership of the party” and “anti-party and counterrevolutionary factional acts.” Kim probably also ordered the deadly attack by the application of a VX nerve agent—one of the most toxic of the chemical warfare agents—against Jong-nam, his half-brother and erstwhile competitor for the position of supreme leader of North Korea. Captured on camera, the attack occurred in Malaysia’s airport, and images of Jong-nam’s gruesome death were circulated around the world.

Kim has made it clear that he will not tolerate any potential challengers. And his rule through terror and repression—against the backdrop of that pastel wonderland of waterparks—means that the terrorized and repressed will continue to feed Kim’s illusions and expectations, his grandiose visions of himself and North Korea’s destiny.

Kim Jong–un has overseen four nuclear tests and debuted ballistic missiles of various ranges, launched from multiple locations. STR/AFP/Getty Images

BIGGER, BADDER, BOLDER

For the past six years, Kim has poked and prodded, testing and pushing the boundaries of international tolerance for his actions, calculating that he can handle whatever punishment is meted out. To a large extent, he has maintained the initiative on the Korean Peninsula, to the frustration of the United States and his neighbors. And as the U.S. and the international community have imposed ever stricter sanctions, Kim has chosen to double down on his nuclear weapons despite the financial consequences and the increasing international isolation.

Just two weeks after North Korean negotiators agreed to the 2012 Leap Day deal with the U.S., which called for a moratorium on Pyongyang’s nuclear and ballistic missile tests in exchange for food aid, the new Kim regime announced its intention to conduct a space launch, using the same ballistic missile technology banned by sanctions. Although that space launch failed, North Korea, despite international condemnation of the April test, had success with its next attempt, when it launched a satellite into orbit in December 2012. By portraying Kim Jong-un as a hands-on leader who personally ordered the rocket launch from a satellite command center, the state media framed their new leader as bold and action-oriented even in the face of widespread international censure. Two months later in February 2013—just a little over a year into Kim’s rule—North Korea conducted its third nuclear test, and Kim’s first.

Under Kim, North Korea has pressed the accelerator on nuclear and missile development and has codified its status as a nuclear-armed state by inscribing that description into the revised constitution it issued in 2012. It has also reinforced Kim’s role in advancing these nuclear capabilities, further solidifying his authority over their use. Kim has overseen three more nuclear tests, and debuted and tested new ballistic missiles of various ranges from multiple locations, including a submarine-launched ballistic missile and, in July and November 2017, intercontinental ballistic missiles.

North Korea shows every indication of making rapid progress toward the ability to threaten the United States and its allies, while also developing an arsenal for survivable second-strike options in the event of a conflict. But it has consistently asserted, as it did in the 2013 Law on Consolidating Position of Nuclear Weapons State, that the regime’s nuclear weapons are for deterrence. Subsequent authoritative statements, including the North Korean foreign minister’s remarks at the United Nations General Assembly in September 2017, have continued to hew to the same line: “[North Korea’s] national nuclear force is, to all intents and purposes, a war deterrent for putting an end to nuclear threat of the U.S. and for preventing its military invasion,” he said, adding that Pyongyang’s ultimate goal is to “establish the balance of power with the U.S.”

In Harm’s Way

In November 2017, North Korea tested intercontinental ballistic missiles with a potential reach of 8,000 miles–putting the entire United States in range.

8,000 miles

While Kim has been developing and demonstrating advanced nuclear weapons capabilities, he has also focused on diversifying the North’s toolkit of provocations to include cyberattacks, the use of chemical and biological weapons, and the modernization of North Korea’s military, which is among the world’s largest armed forces with over 1 million warriors. Kim has presided over high-profile artillery firepower demonstrations, been captured in photographs poring over military plans purported to depict attacks against the United States and South Korea, and has issued inflammatory threats in response to U.S. and international pressure.

The rhetoric has also extended to threats against those who create negative portrayals of North Korea in popular culture. For example, in 2014, the regime said that the release of the movie The Interview—a comedy depicting an assassination attempt against Kim—would constitute “an act of war”; North Korean hackers threatened 9/11-type attacks against theaters that showed the film.

Although a 9/11-type event did not happen, the regime made it clear through a cyberattack that insults against Kim and North Korea would not be tolerated and that the financial consequences for the perpetrators would be dire. North Korean hackers destroyed the data of Sony Pictures Entertainment, the company responsible for producing the film, and dumped confidential information, including salary lists, nearly 50,000 Social Security numbers, and five unreleased films onto public file-sharing sites.

6,000Hackers

North Korea’s army of cyber–disruptors–operating abroad in China, Southeast Asia, and other places–continues to expand its capabilities.

Source: South Korean Ministry of National Defense

Yet, despite all the chest-thumping and bad behavior, Kim is not looking for a military confrontation with the United States. He is rational, not suicidal, and given his almost-certain knowledge of the significant deficiencies in North Korea’s military capacity, he is surely aware that North Korea would not be able to sustain a prolonged conflict with either South Korea or the U.S. Although Kim is aggressive, he is not reckless or a “madman.” In fact, he has been learning how and when to recalibrate. And it is his ability to recalibrate, change course, and shift tactics that requires us to heed Heuer’s warnings about the “weaknesses and biases in our thinking process” and continually challenge our assumptions and perceptions about “patterns of expectations” in North Korea analysis. We have to learn how to incorporate new information about what is driving Kim Jong-un and how we might counter this profound—and ever evolving—national security threat.

It is true that Kim has been emboldened since 2011, and he’s gotten away with a lot: scores of missile test launches, nuclear tests, the probable VX nerve agent attack against his half-brother in Malaysia, a 2015 incident involving a landmine in the DMZ, the Sony hack in 2014 in which North Korean entities wiped out half of Sony’s global network in response to the release of The Interview, and the mistreatment and death of U.S. citizen Otto Warmbier, a student tourist who was detained and sentenced to 15 years of hard labor for alleged hostile acts against the North Korean state. However, Kim has carefully stopped short of actions that might lead to U.S. or allied military responses that would threaten the regime.

That said, he has also been firm in his insistence that he will not give up North Korea’s nuclear weapons, regardless of threats of military attacks or engagement. It is clear that he sees the program as vital to the security of his regime and his legitimacy as the leader of North Korea. He may well be haunted by a very real fear of the consequences of unilateral disarmament.

The North Korean regime has often made reference to the fate of Iraq and Libya—the invasion and overthrow of its leaders—as key examples of what happens to states that give up their nuclear weapons. At the 2017 Aspen Security Forum, Dan Coats, the U.S. director of National Intelligence, said that Kim “has watched … what has happened around the world relative to nations that possess nuclear capabilities and the leverage they have,” and added that the “lesson” from Libya for North Korea is: “If you had nukes, never give them up. If you don’t have them, get them.”

If we unpack this comparison, we can envision how deeply Kim Jong-un might have been affected by the death of Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi. The once “king of kings in Africa,” who ruled Libya for four decades, was captured by rebels in October 2011, a date well into the process of grooming Kim for leadership and just two months before Kim Jong-il’s death. Graphic images of the bloodied Qaddafi ricocheted around the world. Contemporary reports described how Qaddafi was captured, hacked and beaten by a mob, shirtless and bloody, his body then stored in a freezer.

As Kim assumed his status as the newly anointed leader of North Korea, it’s likely that this imagery was seared in his brain. And Washington’s promises of a brighter future for North Korea if it denuclearized probably seemed hollow to the regime in Pyongyang. The North’s foreign ministry said at the time that the Libya crisis showed that the U.S.-led effort to coax Libya to give up its weapons of mass destruction had been “an invasion tactic to disarm the country.”

Moreover, Qaddafi’s death occurred during the so-called Arab Spring, when a wave of popular protests against authoritarian regimes convulsed the Middle East and North Africa between 2010 and 2011. The overthrow of regimes hitherto believed to be invincible probably highlighted for Jong-un the potential consequences of showing any signs of weakness, and reinforced the brutal suppression of dissent practiced by the Kim dynasty.

Even without all these warning signs, however, it is unlikely that Kim would have given serious consideration to denuclearizing his country. For him and his generation, people who came of age in a nuclear North Korea, the idea of disarming is probably an alien concept, an artifact of a distant “pre-modern” time that they see no advantage to revisiting, especially given the Trump administration’s hints about “preventive war” and the president’s own tweets threatening “fire and fury” against Kim and “military solutions [that] are now fully in place, locked and loaded.”

Dusk falls on Pyongyang, where three generations of Kims have ruled since the country’s founding in 1948. David Guttenfelder/National Geographic Creative

EDGING TOWARD HUBRIS

North Korea’s highly provocative actions in the summer and fall of 2017—demonstrating ICBMs, conducting a test of a probable thermonuclear device, and threatening to detonate a hydrogen bomb over the Pacific—suggest that Kim’s confidence has grown over the past six years. After all, he has outlasted both South Korean president Park Geun-hye and President Barack Obama. Perhaps he thinks he can out-bully and out-maneuver President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping as well.

Such confidence may be bolstered by the fact that Kim has yet to face a real “crisis” of the kind his father and grandfather had to confront and manage. He has relied on military demonstrations and provocative actions to get his way, and has no experience in the arts of negotiation, compromise, and diplomacy.

Qualifications by Generations

Given the steady drumbeat of internal purges, the sidelining of North Korea’s diplomats since 2011 because of Kim’s focus on advancing his nuclear weapons program and conventional capabilities, and Kim’s apparent reveling in his recent war of words with President Trump—Kim called Trump “mentally deranged” in response to Trump’s personal attacks against Kim in his tweets and speech to the U.N. General Assembly in September—it would take a very brave North Korean official to counsel dialogue and efforts to mollify Washington and Beijing. Instead, Kim’s use of repression and his conferring of financial benefits and special privileges to loyalists has probably encouraged sycophants and groupthink within his inner circle, fueling his preference for violence and aggression.

But he may be reaching a critical point where he has to make a strategic choice. While Kim has avidly pursued nuclear weapons, he is also, in accord with his announced policy of byungjin, deeply invested in improving the North Korean economy—certainly a tall order given the gravity of internal changes, the weight of sanctions, and Beijing’s willingness to apply stronger pressure than we have seen before. Trends in North Korea’s internal affairs, such as greater information penetration from the outside world, loosening of state control over resources and markets, the rise of consumerism, and the growth of a moneyed class, will also place severe stresses on the Kim regime.

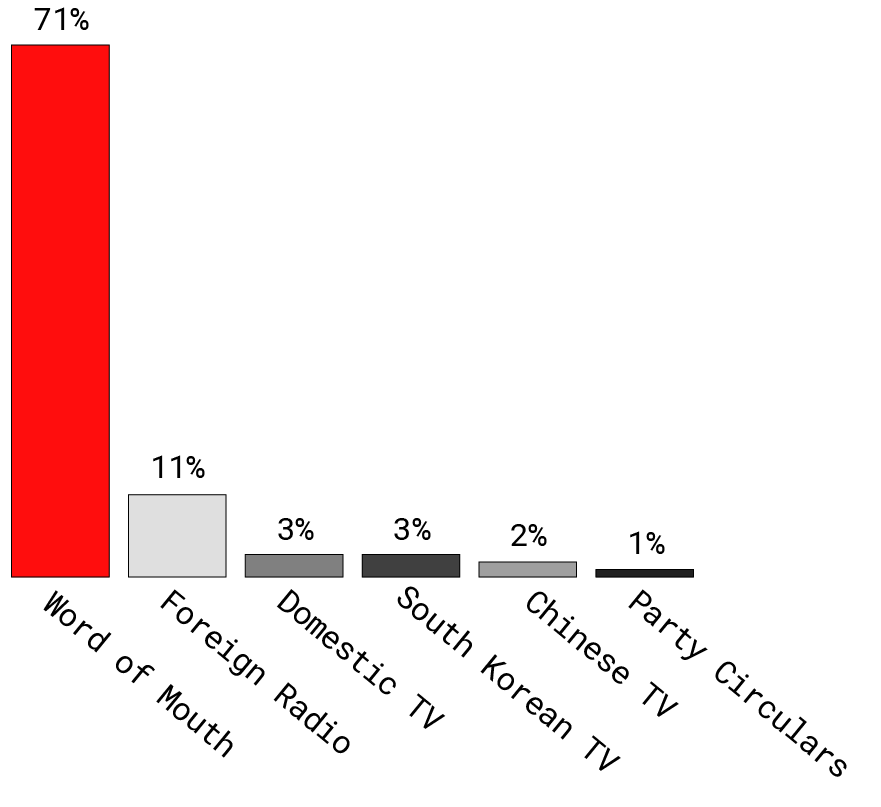

How North Koreans Get Their News Source: InterMedia

Source: InterMedia

At the same time, international pressure on North Korea has never been greater. A number of recent actions have the potential to squeeze North Korea’s ability to earn hard currency for the regime to fund its economic and military goals, including: recent U.N. Security Council resolutions, such as the latest UNSCR 2397 in response to North Korea’s ICBM test in November; successful U.S. efforts to compel countries—including China—to cut off trade and financial links with North Korea; and President Trump’s September 21, 2017 executive order imposing new sanctions on North Korea (and authorizing broad secondary sanctions). These efforts also have the potential to undermine Kim’s ability to reward elites and suppress their ability to make money for themselves or raise money for loyalty payments to the regime.

The combined weight of all these pressures, internal and external, on North Korea, coming precisely at a time of rising expectations within the country, may overwhelm the regime—unless Kim learns to dial back his aggression. That, of course, is a big if.

We should be concerned about Kim’s hubris. In 2012, when Kim gave his first public speech, he ended with the line, “Let’s go on for our final victory.” At the time, despite the fact that it was delivered against the backdrop of a military parade featuring the biggest display of Korean weapons ever to have been seen by the world, it sounded to me like the bluster of a new, young leader. For all we know he may have been posturing then, but given recent developments and Kim’s likely increased confidence about his ability to call the shots, the U.S. and its partners and allies, including China, must be clear-eyed about the potential for Kim to shift his stated defensive position to a more aspirational one.

I still agree with the U.S. intelligence community’s assessment that “Pyongyang’s nuclear capabilities are intended for deterrence, international prestige, and coercive diplomacy,” as the director of National Intelligence testified in early 2017. But I believe it would be a mistake to extrapolate Kim’s future intentions from his past pronouncements and actions because we do not and will never have enough information about North Korea’s intentions and capabilities that will make us feel certain about our understanding of Kim. He and his country do not exist in an ahistorical space that is unchanging and static. Our analysis and policy responses must also change and evolve and be prepared for all potential scenarios. We, too, must avoid edging toward hubris.

Even as we parse every statement issued by North Korea, the country’s media content, the satellite imagery of its infrastructure, the state-sponsored videos, and the testimonies of defectors, we must remember that Kim is watching us as much as we are watching him. The U.S. must work to minimize the threat of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program without fueling conditions that could invite unintended escalation leading to armed conflict. The U.S. has opportunities to reshape Kim’s calculus, constrain his ambitions, and cause him to question his current assumptions about his ability to absorb increasing external pressure. Bobby Yip/Reuters

Bobby Yip/Reuters

As I have written elsewhere, we can still test Kim’s willingness to pursue a different course and shift his focus toward moves that advance denuclearization. We can do so through strengthening regional alliances—especially with South Korea and Japan—that are demonstrably in lockstep on the North Korea issue. We can also increase stresses on the North Korean regime by cutting off resources that fund its nuclear weapons program and undermine Kim’s promise to bring prosperity to North Koreans, and ramp up defensive and cyber capabilities to mitigate the threat posed by North Korea against the U.S. and its allies. We should also intensify pressure on the regime through information penetration, raising public awareness of Pyongyang’s human rights violations, and create a credible, alternative vision for a post-Kim era to encourage defections.

Kim Jong-un is still learning. Let’s make sure he’s learning the right lessons.

Jung H. Pak is a senior fellow and the SK-Korea Foundation Chair in Korea Studies at the Brookings Institution’s Center for East Asia Policy Studies. She focuses on the national security challenges facing the United States and East Asia, including North Korea’s weapons of mass destruction capabilities, the regime’s domestic and foreign policy calculus, internal stability, and inter-Korean ties. She has held senior positions at the Central Intelligence Agency and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Prior to her work in national security, Pak taught U.S. history at Hunter College in New York City and studied in South Korea as a Fulbright Scholar.

THE EDUCATION OFKIM JONG–UNBY JUNG H. PAKFebruary 2018한국어

WHEN NORTH KOREAN STATE MEDIA reported in December 2011 that leader Kim Jong-il had died at the age of 70 of a heart attack from “overwork,” I was a relatively new analyst at the Central Intelligence Agency. Everyone knew that Kim had heart issues—he had suffered a stroke in 2008—and that the day would probably come when his family’s history of heart disease and his smoking, drinking, and partying would catch up with him. His father and founder of the country Kim Il-sung had also died of a heart attack in 1994. Still, the death was jarring.

While North Koreans wept, fainted, and convulsed with grief, feigned or not, Kim Jong-un, the twenty-something-year-old son of Kim Jong-il, reportedly closed the country’s borders and declared a state of emergency. News of these events began to filter out to the international media through cell phones that had been smuggled in before Kim Jong-il’s death.

There had been signs before 2011 that Kim was grooming his son for the succession: he began to accompany his father on publicized inspections of military units, his birth home was designated a historical site, and he began to assume leadership titles and roles in the military, party, and security apparatus, including as a four-star general in 2010.

In response to the death, South Korea convened a National Security Council meeting as the country put its military and civil defense on high alert, Japan set up a crisis management team, and the White House issued a statement saying that it was “in close touch with our allies in South Korea and Japan.” Back in Langley, I remember being watchful for any indications of instability, as I began to develop my thinking on what was happening and where North Korea might be headed under the newly named leader. Immediately after Kim Jong-il’s death was announced, the North Korean state media made it clear that Jong-un was the successor: “At the forefront of our revolution, there is our comrade Kim Jong-un standing as the great successor … ”

Pyongyang residents mourn the death of their leader, Kim Jong-il, in December 2011. Reuters/Kyodo

Pyongyang residents mourn the death of their leader, Kim Jong-il, in December 2011. Reuters/KyodoWhat sort of person was Kim Jong-un? Would he even want the burden of being North Korea’s leader? And if so, how would he govern and conduct foreign affairs? What would be his approach to the nuclear weapons program that he inherited? Would the elites accept Kim? Or would there be instability, mass defections, a flood of refugees, bloody purges, a military coup?

Predictions about Kim’s imminent fall, overthrow, or demise were rife among North Korea and Asia watchers. Surely, someone in his mid-20s with no leadership experience would be quickly overwhelmed and usurped by his elders. There was no way North Koreans would stand for a second dynastic succession, unheard of in communism, not to mention that his youth was a critical demerit in a society that prizes the wisdom that comes with age and maturity. And if Kim Jong-un were to hold onto his position, what would happen to his country? North Korea was poor and backward, isolated, unable to feed its people, while clinging to its nuclear and missile programs for legitimacy and prestige. Under Kim Jong-un, the collapse of North Korea seemed more likely than ever.

That was then.

In the six years since, Kim has collected a number of honorifics, cementing his position as North Korea’s leader. Kim has carried out four of North Korea’s six nuclear tests, including the biggest one, in September 2017, with an estimated yield between 100-150 kilotons (the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan during World War II was an estimated 15 kilotons). He has also tested nearly 90 ballistic missiles, three times more than his father and grandfather combined. North Korea now has between 20 and 60 nuclear weapons and has demonstrated ICBMs that appear to be capable of hitting the continental United States. It could also be on track to have up to 100 nuclear weapons and a variety of missiles—long-range, road-mobile, and submarine-launched—that could be operational as early as 2020. Under Kim, North Korea has conducted major cyberattacks and reportedly used a chemical nerve agent to kill Kim’s half-brother at an international airport.

The last six years have also seen Kim dotting the North Korean landscape with ski resorts, water parks, and high-end restaurants to showcase the country’s modernity and prosperity to internal and external audiences. They are also meant to deliver on his promise to improve the people’s lives—as part of his byungjin policy of developing both the economy and nuclear weapons capabilities—and to attract foreign tourists.

Yet even as he is modernizing his country at a furious pace, Kim has deepened North Korea’s isolation. Having rebuffed U.S., South Korean, and Chinese attempts to reengage, he has refused to meet with any foreign head of state, and so far as is known, since becoming leader his significant foreign contacts have been limited to Kenji Fujimoto, a Japanese sushi chef whom he knew in his youth and whom he invited to Pyongyang in 2012, and Dennis Rodman, an American basketball player, who has visited North Korea five times since 2013.

Kim Jong-un is here to stay.

Of Missiles and Men

The pace of weapons testing is speeding up. Kim Jong-un has already tested nearly three times more missiles than his father and grandfather combined.

Source: James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies/Nuclear Threat Initiative

Source: James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies/Nuclear Threat Initiative

A painting of the late North Korean leaders Kim Il-sung (L) and Kim Jong-il hints at the opaqueness of the Hermit Kingdom. Jason Lee/Reuters

THE TEN-FOOT-TALL BABY

North Korea is what we at the CIA called “the hardest of the hard targets.” A former CIA analyst once said that trying to understand North Korea is like working on a “jigsaw puzzle when you have a mere handful of pieces and your opponent is purposely throwing pieces from other puzzles into the box.” The North Korean regime’s opaqueness, self-imposed isolation, robust counterintelligence practices, and culture of fear and paranoia provided at best fragmentary information.

Intelligence analysis is difficult, and not intuitive. The analyst has to be comfortable with ambiguity and contradictions, constantly training her mind to question assumptions, consider alternative hypotheses and scenarios, and make the call in the absence of sufficient information, often in high-stakes situations. To cultivate these habits of mind, we were required to take courses to improve our thinking. Walk into any current or former CIA analyst’s office, and you will find a slim, purple book by Richards Heuer with the title Psychology of Intelligence Analysis. This is required reading for CIA analysts. It was presented to us during our initial education as new CIA officers and often referred to in subsequent training. It still sits on my shelf at Brookings, within arm’s reach. When I happen to glance at the purple book, I am reminded about how humility is inherent in intelligence analysis—especially in studying a target like North Korea—since it forces me to confront my doubts, remind myself about how I know what I know and what I don’t know, confront my confidence level in my assessments, and evaluate how those unknowns might change my perspective.

Anita Kunz/The New Yorker

Anita Kunz/The New YorkerHeuer, who worked at the CIA for 45 years in both operations and analysis, focused his book on how intelligence analysts can overcome, or at least recognize and manage, the weaknesses and biases in our thinking processes. One of his key points was that we tend to perceive what we expect to perceive, and that “patterns of expectations tell analysts, subconsciously, what to look for, what is important, and how to interpret what is seen.” The analyst’s established mindset predisposes her to think in certain ways and affects the way she incorporates new information.

What, then, are the expectations and perceptions that we need to overcome to form an accurate assessment of Kim Jong-un and his regime? Given the over-the-top rhetoric from North Korea’s state media, Kim’s own often outrageous statements, and the hyperbolic imagery and boastful platitudes perpetuated by the ubiquitous socialist realism art, it has been only too easy to reduce Kim to caricature. That is a mistake.

When the focus is on Kim’s appearance, there’s a tendency to portray him as a cartoon figure, ridiculing his weight and youth. Kim has been called—and not just by our president—“Rocket Man,” “short and fat,” “a crazy fat boy,” and “Pyongyang’s pig boy.” A New Yorker cover from January 18, 2016, soon after North Korea’s fourth nuclear test, portrayed him as a chubby baby, playing with his “toys”: nuclear weapons, ballistic missiles, and tanks. The imagery suggests that, like a child, he is prone to tantrums and erratic behavior, unable to make rational choices, and liable to get himself and others into trouble.

However, when the focus is on the frighteningly rapid pace and advancement of North Korea’s cyber, nuclear, and conventional capabilities, Kim is portrayed as a ten-foot-tall giant with untold and unlimited power: unstoppable, undeterrable, omnipotent.

The coexistence of these two sets of overlapping perceptions—the ten-foot-tall baby—has shaped our understanding and misunderstanding of Kim and North Korea. It simultaneously underestimates and overestimates Kim’s capabilities, conflates his capabilities with his intentions, questions his rationality, or assumes his possession of a strategic purpose and the means to achieve his goals. These assumptions distort and skew our policy discussions.

A woman in Pyongyang walks past a billboard advertising North Korea’s missile prowess. The capital city is rife with stylized propaganda. David Guttenfelder/National Geographic Creative

FOOTSTEPS OF GENERAL KIM

If he had followed Korean custom and tradition, Kim Jong-il would have named Kim Jong-nam, not Kim Jong-un, his successor, because Jong-nam was the eldest of his three sons. But Kim Jong-il reportedly rejected Jong-nam as being unfit to lead North Korea. Why? For one, the elder Kim might have judged that Jong-nam was tainted by foreign influence. In 2001 Jong-nam had been detained in Japan with a fake passport in a failed attempt to go to Tokyo Disneyland. More seriously, it is said that he had suggested that North Korea undertake policy reform and open up to the West, enraging his father.

The second son, Jong-chul, was deemed too effeminate; one of Jong-chul’s friends recalled that “[Jong–chul] is not the type of guy who would do something to harm others. He is a nice guy who could never be a villain.” Indeed, he seems to be playing an unspecified supporting role in his younger brother’s regime.

All in the family

Four generations of Kims: A selective history*

*North Korea’s secrecy makes it difficult to verify information about Kim Jong-un’s children, including how many there are and when they were born. His wife’s birth date is also unconfirmed.

*North Korea’s secrecy makes it difficult to verify information about Kim Jong-un’s children, including how many there are and when they were born. His wife’s birth date is also unconfirmed.That left Jong-un, whom the elder Kim chose to be the third Kim to lead North Korea because he was the most aggressive of his children. Kenji Fujimoto, Kim Jong-il’s former sushi chef, who visited Pyongyang at the request of Kim Jong-un, has provided some of the most fascinating firsthand observations about Jong-un and his relationship with his father. Fujimoto claims that Jong-il had chosen his youngest son to succeed him as early as 1992, citing as evidence the scene at Jong-un’s ninth birthday banquet where Jong-il instructed the band to play “Footsteps” and dedicated the song to his son: Tramp, tramp, tramp; The footsteps of our General Kim; Spreading the spirit of February [a reference to Kim Jong-il, who was born in February]; We, the people, march forward to a bright future. Judging from the lyrics, Jong-il was expecting Kim Jong-un to lead North Korea into the future, guided by the spirit and legacy of his father.

Though Jong-il saw in his son a worthy successor to the dynasty, there are critical differences between the first two Kims and Kim Jong-un. Kim Il-sung, the country’s founder and Jong-un’s grandfather who ruled for nearly five decades until his death in 1994, was a revolutionary hero who fought Japanese imperialism, the South Korean “puppets,” and the American “jackals” in a military conflict that ended only because of an armistice.

In the next generation Kim Jong-il had to navigate through world-changing events that included the collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent end of large-scale aid from Moscow, a changing relationship with the ever-suspicious Chinese who seemed to be prioritizing links with Seoul, and tense negotiations with the United States on North Korea’s burgeoning nuclear program. And let’s not forget the famine and the drought of the 1990s, or the tightening noose of sanctions and international ostracism.

In contrast with his battle-hardened elders, Kim Jong-un grew up in a cocoon of indulgence and privilege.

1990sChicago Bulls

Kim Jong-un has a well-known love of basketball. According to a GQ interview, it began when a Japanese contact sent him VHS tapes of Chicago Bulls‘ playoff games.

During the 1990s famine, in which as many as 2–3 million North Koreans died as a result of starvation and hunger-related illnesses, Kim was in Switzerland. His childhood was marked by luxury and leisure: vast estates with horses, swimming pools, bowling alleys, summers at the family’s private resort, luxury vehicles adapted so that he could drive when he was 7 years old. For Kim, skiing in the Swiss Alps and swimming in the French Riviera must have seemed part of his birthright. Kim had a temper, hated to lose, and loved Hollywood movies and basketball player Michael Jordan.

Fujimoto, the sushi chef, has described Jong-un’s mother as not very strict about education and says that he was never forced to study. His friend and classmate in Switzerland said of Kim: “We weren’t the dimmest kids in the class but neither were we the cleverest. We were always in the second tier … The teachers would see him struggling ashamedly and then move on. They left him in peace.” Jong-un was apparently unbothered by his less-than stellar scores; as his classmate noted, “He left without getting any exam results at all. He was much more interested in football and basketball than lessons.”