Moon Over Korea

E. Tammy Kim

August 16, 2018 issue

Submit a letter:

Email us letters@nybooks.com

Reviewed:

Moon Jae-in eui Unmyeong [The Destiny of Moon Jae-in]

by Moon Jae-in

Seoul: Bookpal, 488 pp., ₩15,000

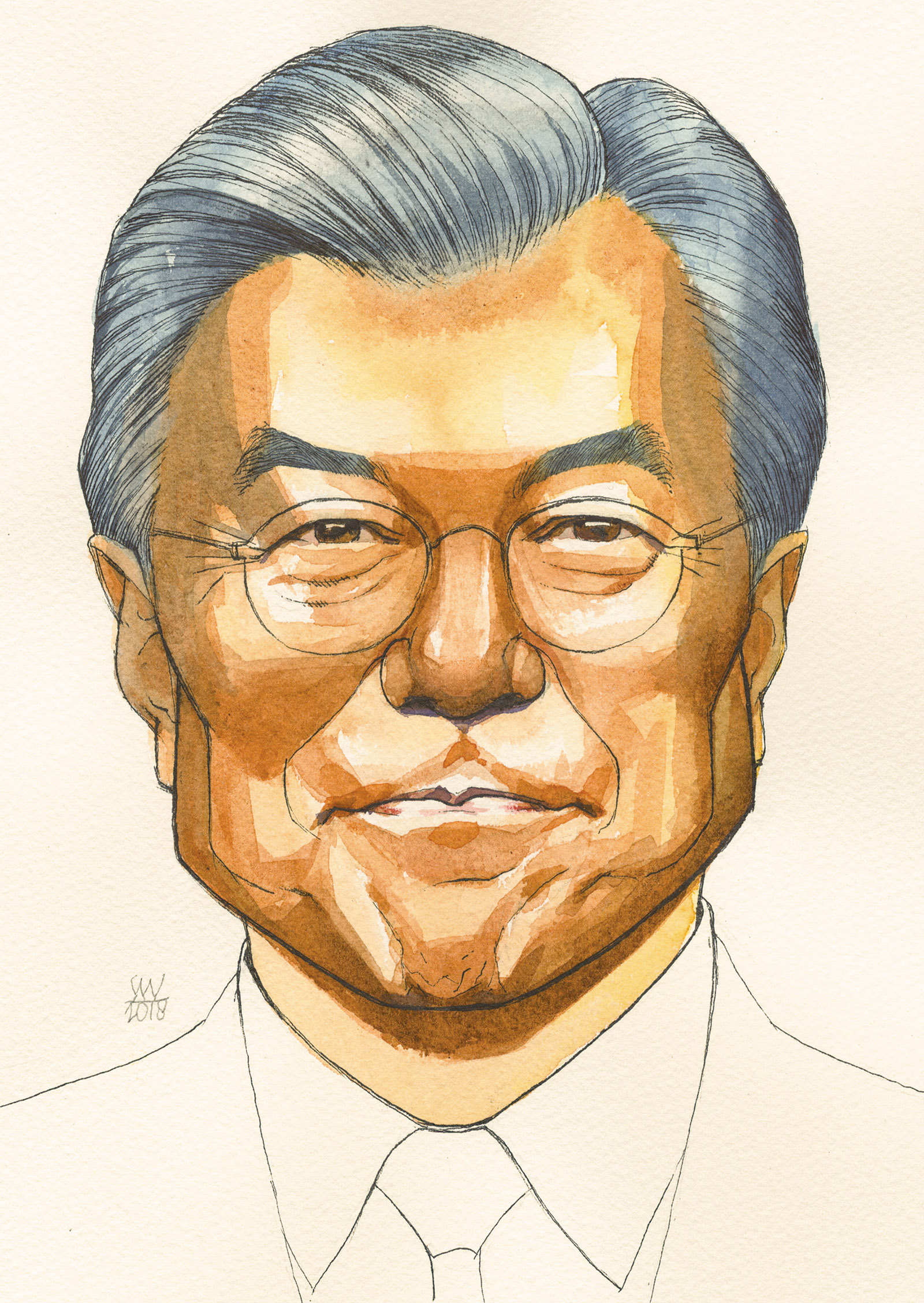

Moon Jae-in; drawing by Siegfried Woldhek

Moon Jae-in; drawing by Siegfried WoldhekBuy Print

In Singapore on June 12, as Donald Trump vigorously shook hands with North Korea’s Kim Jong-un, the man behind this improbable meeting leaned forward in his chair and smiled. South Korean president Moon Jae-in, just thirteen months into his five-year term, had helped arrange the first-ever summit between an American president and the leader of North Korea. Yet Moon was careful to keep a respectful distance. He watched on a television monitor in the Blue House, the presidential compound in Seoul. It was, however symbolic, a goal he had pursued over two decades in politics, and it brought him a step closer to healing familial and national wounds. Moon is a child of the Korean War, the son of refugees from the pre-division North. But unlike Trump and Kim, who swapped boasts and missile threats just months before their handshake, Moon didn’t feel the need to take credit.

The meeting between Trump and Kim, beyond its cinematic, exaggerated quality, represented the final leg of a diplomatic relay—the US and South Korea, North and South Korea, and finally the US and North Korea. It was a relay in another sense, too: Moon had overseen the last substantial round of multilateral negotiations with North Korea, in 2007, which resulted in inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency and suspension of the Yongbyon nuclear reactor, at least for a time. Moon was then the chief of staff to President Roh Moo-hyun, his mentor and former law partner, who was finishing up his term. In October of that year, Roh became only the second South Korean president to cross the 38th parallel, where he met with Kim Jong-un’s father, Kim Jong-il. In Moon’s memoir, The Destiny of Moon Jae-in, he writes that this North–South summit was “the most important thing I did as chief of staff.”

Moon’s ascent to the presidency, after a decade of hard-right rule, reads like Korean melodrama. He was elected in May 2017 following the impeachment of Park Geun-hye, the daughter of General Park Chung-hee, who ruled South Korea from 1963 to 1979. In the fall of 2016, it was revealed that Park fille had secretly outsourced presidential decision-making to an old friend, opening up the Blue House to bribes from major corporations. Park had already shown herself to be incompetent and cruelly aloof, as in 2014 when hundreds of students were killed in a preventable ferry accident and she failed to address a nation in profound despair. Through subzero temperatures, some 17 million South Koreans attended months of sit-ins to call for Park’s ouster and to protest corruption in the Blue House. Moon, then the leader of the opposition Democratic Party, became a regular of the Candlelight Movement, in his puffy coat and leather gloves. By May 2017, Park was impeached and jailed, and Moon elected president. He promised voters “A New Korea” and “People First.”

The “destiny” of the title of Moon’s memoir refers to his friendship with Roh and the peculiar, often tragic, circumstances that shaped their lives. But while Moon is undoubtedly Roh’s heir, he is also a new kind of Korean leader: a principled liberal and an idealist intent on building a more accountable, less venal democracy. I spent much of May and June in Korea, soaking up the atmosphere of progress and expectation that contrasted so sharply with the news in the US. The mood of the Candlelight Movement—a revolution, really—had not faded, and spirited debates over feminism, housing, labor reform, and the North Korean peace process could be heard in cafés, restaurants, and parks. For the first time in many years, there was a sense that South Korean politics might evolve beyond the denunciation of progressive social policies as North Korean imports. Everyone I spoke with about Moon, including his critics, pronounced him “fundamentally decent.” He is an unnatural politician, exhausted by talking points and grandstanding. His wife, Kim Jung-sook, once said of her husband, “I felt his honesty and upright character was not a good fit for his success in politics.”

Moon has cited Franklin Roosevelt as a role model, for his blending of “liberal principle and unifying leadership,” a feat not yet accomplished in South Korea. Though the republic is seventy years old, its democracy dates only to 1987. Its politics are split between liberals and conservatives, their parties named and renamed, cleaved and reconstituted. One’s left- or right-wing bona fides hinge less on a philosophy of economic redistribution than on historiography. What is needed to resolve the scars (comfort women, territorial disputes, history textbooks) of Japanese colonization? Was Park Chung-hee a modernizer and anti-Communist savior or a despot and colonial collaborator? Is the United States a military ally or an occupying force on the peninsula?

Twentieth-century Korea has produced an abundance of personal trajectories that intersect with world-historical events. Yet even by these standards, Moon Jae-in’s is an extraordinary life. He was born on the small southern island of Geoje in 1953, where his parents, displaced by fighting in Korea’s northeast, were settled by US forces. They had been among some 14,000 Koreans aboard the SS Meredith Victory, the largest-ever evacuation by ship. Moon’s parents had expected to return home within a few weeks, but as the war stretched on, they moved from Geoje to the port city of Busan. The family of seven—Moon has four siblings—was desperately poor and often went hungry. As a boy, Moon helped his mother sell charcoal cylinders (for cooking and underfloor heating) and recalls being embarrassed by the dark smudges on his face and school uniform. His father, whom he revered, tried and failed at various business ventures, and never recovered from the trauma of dislocation.

Advertisement

Moon was bright, athletic, and introspective. He tested into the best middle and high schools in Busan, and spent his afternoons and evenings at the library. All that reading, and the gap in wealth he saw between himself and his elite classmates, made him world-wise. “You mature quickly when you’re poor,” he writes. In his teenage years, he earned the punning nickname Moon Je-ah, or “problem child,” and failed to get into the top tier of colleges. He received a scholarship to Kyunghee University, where he majored in law (a graduate degree was not required to become an attorney) and sublimated his rebellious streak into student organizing. It was 1975, and the nation was still under the dictatorship of Park Chung-hee, who had been trained in elite Japanese military academies. Park imposed a curfew, censored the press, tortured dissenters, and banned public gatherings in the name of rooting out North Korean sympathizers. Moon, like thousands of other student and labor activists at the time, was arrested, jailed, and expelled from school.

At the end of Moon’s first stint in prison, he was conscripted into the military. He was assigned to an airborne unit in the special forces, less an honor than a punishment reserved for rabble rousers. Though Moon opposed the government, he took surprisingly well to the rhythms of military life (and picked up a love of scuba diving). In 1976 he was sent to help defuse an incident along the border with North Korea that threatened to escalate into war. Two American soldiers had tried to cut down a poplar tree that blocked their line of sight and were killed with their own axes by North Korean troops. Moon later received a commendation from General Chun Doo-hwan, who would come to power in a coup d’état after Park was assassinated by his own chief of national intelligence.

Shortly after Moon returned home from the military, his father died of a heart attack at the age of fifty-nine. Moon was shattered. “My father had always wanted to return to his hometown,” he writes, “but passed away without even knowing whether his parents were dead or alive. He never adjusted to life in the South—a disempowering, exhausting life.” In his grief, he managed to study for the bar exam and was allowed to finish his degree. He returned to activism as well, and was again jailed in 1980. It was from his prison cell that he heard that he had passed the bar.

He then met Roh Moo-hyun, a blunt, charismatic autodidact, and joined his law firm back in Busan. The men took on a mix of cases, but soon became the preferred advocates for student organizers, labor leaders, and unlucky locals caught in the dragnet of Chun’s military dictatorship. Beginning in the late 1980s, Roh pursued a career in politics, vowing to dismantle Korea’s stifling geographic factionalism (which pitted the conservative southeastern Gyeongsan region against the more liberal Jeolla area in the southwest), a goal Moon would eventually inherit. Roh replaced the conservative Lee Myung-bak in the National Assembly in 1998; in 2000 he took a cabinet position in the administration of the liberal president Kim Dae-jung (from Jeolla), the first South Korean leader to meet with a North Korean head of state.

In 2002, Roh eked out a presidential win and convinced Moon, against his better instincts, to set litigation aside and become the senior secretary for civil affairs. It was a terrible fit. Over the course of that first year, Moon was so stressed by the politicking and media relations that he lost ten teeth and gained twenty pounds. (He remains self-conscious about the lisp caused by his dental implants.) He handed in his resignation and departed for a long trek through the Himalayas, without his cell phone.

One day in Nepal, Moon glimpsed a shocking headline in the International Herald Tribune. The words “Roh” and “impeachment” put him on a flight back home. Elections were imminent, and Roh had endorsed liberal candidates for the National Assembly, violating the prohibition against campaigning by a sitting president. Legislators passed a bill of impeachment that was then sent to the Constitutional Court, a process Moon called “dangerous” and undemocratic. As the nation waited for a verdict, Roh’s supporters, donning their customary yellow, protested in the streets and at the polls. Roh’s party swept the election, and the court declined to impeach him. Moon returned to the Blue House, but this time as chief of staff, a less public, more technocratic role.

Advertisement

Roh was perhaps the most left-wing president in South Korea’s (admittedly short) history, and his harsh tongue and populist image made him all the more polarizing. With regard to North Korea (and despite the diplomatic toll of the Iraq War and George W. Bush’s “Axis of Evil”), Roh oversaw several reunions of separated families, met with Kim Jong-il, and participated in the fifth round of the Six-Party Talks on denuclearization. The 2004 family reunions were memorable for Moon: he went with his mother to Mount Kumgang in North Korea, where she embraced her younger sister for the first time in fifty-four years. “Just once, I’d like to see Heungnam, in South Hamgyeong province, the place my parents fled during the war,” Moon has said.

In 2009, a year after Roh and Moon left the Blue House, Roh was alleged to have taken bribes. Even though the scale was minor, the allegation was true—there had been gifts and favors. The new president was Roh’s rival Lee Myung-bak, and the prosecution appeared vengeful. In May of that year, Roh committed suicide by leaping from a cliff behind his home. “It was the most painful, unbearable day of my life,” Moon writes in Destiny. This trauma drew hundreds of thousands of mourners into the streets, and Moon back into politics. In 2012 he made a late-stage bid for the Blue House, losing narrowly to Park Geun-hye, the daughter of the man he had battled as a college activist. Five years later, propelled by rallies attended by a third of the Korean population and the impeachment process he once bitterly criticized, he replaced her.

To those involved in North–South reunification efforts, Moon brings relief after a decade of hard-right rule. The Lee and Park administrations had rejected the “sunshine” politics of Roh and Kim Dae-jung and approached the North with harsh rhetoric and the withholding of economic exchange. There were moments of extreme tension: in 2010, North Korea fired on a South Korean island and is thought to have sunk a South Korean navy ship; in 2011 Kim Jong-un took power after his father’s death; and in 2016–2017 North Korea lobbed missiles and traded insults with South Korea and the US. South Korean activists were muzzled, and a far-left party was disbanded by Park’s Constitutional Court.

Chung Sung-Jun/Getty Images

A South Korean boy at a rally in support of the US–North Korea summit, Seoul, June 2018

Kim Hyung-tae, a prominent human rights lawyer in Seoul, has represented many clients who were persecuted under Lee and Park—both of whom have since been imprisoned. Kim himself was investigated and accused of Communist ties. “When you’ve struggled so long, it’s odd to feel comfortable,” he told me in his Gangnam office. I visited one of his clients, Oh Hye-ran, whose pacifist organization was ransacked by the authorities and only recently acquitted of violating the National Security Law. She described Moon as “playing it safer than Roh,” while remaining cognizant of his roots in the Candlelight Movement.

Kathleen Stephens, the US ambassador to South Korea from 2008 to 2011, told me that Moon is applying what he learned as chief of staff. He began the North Korean peace process early, not waiting until the “lame duck” months of his term,

and has signaled that he will “stay lashed up with the US” and respect the alliance. Wi Sung-lac, South Korea’s former ambassador to Russia and a chief negotiator during the Six-Party Talks, sees Moon as “pursuing a policy of dialogue and negotiation” quite distinct from that of his predecessors.

In person, Moon transmits sincerity more than charisma, but he is unmistakably shrewd. This was on clear display in late May, when, after Trump unilaterally canceled the planned US–North Korea summit, Moon made an impromptu trip to see Kim Jong-un—and lured Trump back to the table. When Moon took the job of Democratic Party chief in 2015, he did not hesitate to recruit advisers and National Assembly candidates from unlikely places. The day after the Singapore summit, I had dinner with Cho Eung-cheon, who represents the city of Namyangju, northeast of Seoul. It was the night of the local elections, and the landslide for Moon’s party was already evident. “The opposition still hasn’t absorbed the lesson of the Candlelight Movement,” Cho said, referring to its lack of a socioeconomic platform. “They’re just objecting to whatever Moon does.”

Cho identifies as conservative and ardently capitalist. He is a former prosecutor who served in several successive administrations until he was fired by Park Geun-hye for raising ethics concerns and allegedly leaking an incriminating document. He ran a restaurant for a time and then, in 2016, was tapped by Moon to run for office as a Democratic Party representative. “When I was scouted, the party was in disarray,” Cho told me. “People were fleeing. Moon needed to renew the party and bring in new people, so he recruited a bunch of specialists. I said, ‘Okay, but only if you don’t try to change me.’ I can’t stand the left wing of the party.” Cho praised Moon’s pragmatism and his summits with Pyongyang, but said that he must now focus on domestic concerns: “The president has won all the points he can from North Korean diplomacy. Now he can only lose points, if something goes wrong.”

Though the Candlelight Movement wasn’t aimed at Kim Jong-un, Moon understands that some resolution with the North is a prerequisite for saner political discourse in the South. (As Joseph Yun, who recently left his post as special representative for North Korea policy at the US Department of State, told me, it’s critical for Americans to understand “how much of a domestic political issue North Korea is in South Korea.”) Moon wants to evolve beyond the usual scenario in which a commitment to reduce poverty or establish a more robust welfare state provokes a crackdown on South Korean leftists as Communist rebels.

In South Korea, despite the consumerist bustle of Seoul, the construction frenzy in nearby Pyeongtaek, and the nation’s rather respectable growth rate of 3.1 percent, wages remain low, and inequality is high. Residents are especially anxious about the plight of retirees as well as of millennials, a key constituency of Moon’s. Though tame by the standards of Spain or France, the youth unemployment rate of 10 percent has become a synecdoche for a range of socioeconomic frustrations: the bruising, conformist educational system; unaffordable housing; a patriarchal and hierarchical office culture; and the fetishization of chaebol, the mega-conglomerates, like Samsung and LG, that dominate Korean society. In Because I Hate Korea, a best-selling novel published in 2015, the young-adult narrator bemoans a labor market that makes her feel “about as special as a paving stone.”

The economic agenda laid out by Moon includes 810,000 new public-sector jobs (5 percent of which would be set aside for young people), support for small businesses, child-care benefits, a shortened workweek, an increase in the minimum wage, expanded public rental housing, subsidies for rural laborers, and an anticorruption drive. It’s an ambitious list that’s already proving difficult to achieve. After successfully pushing to raise the minimum wage and cap weekly work hours, Moon agreed to modifications that benefit employers. Lee Jeong-mi, head of the left-wing Freedom Party, said at a recent press conference, “The ruling party should be focused not on coddling corporations, but on realizing the goals of the Candlelight Revolution.” The Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU) has led protests against Moon’s compromise on the minimum wage and his refusal to pardon imprisoned labor leaders, calling him a “neoconservative.” At a press conference I attended in late May, Han Sang-gyun, a former auto worker and KCTU leader who was jailed under Park Geun-hye, said, “This is not only the moment to pursue South–North relations, but also to reform the deep-seated problems of the chaebol economy. If Moon doesn’t act on his commitments, he could lose public support.”

At the end of June, I met with a spokeswoman for Moon at the Blue House, and asked what she thought Americans needed to know. Her first response was to correct the “misperception” that Moon is “anticapitalist or anti-chaebol.” It was a reasonable-enough comment: the US foreign policy establishment tends to stereotype, and thus dismiss, Korean liberals as anticorporate, anti-Washington, and pro-Pyongyang. In Korea, however, Moon seems more vulnerable to criticism from the left. Last year he was condemned by progressives when, during a debate with the conservative Liberty Korea Party leader Hong Joon-pyo (who resigned just a few weeks ago, after the June 13 elections that proved so disastrous for his party), Moon said that he “dislikes” homosexuality. (He is a devout Catholic.)

And in recent weeks, he has remained silent on the fate of some 550 Yemeni asylum seekers on Jeju Island, even as his justice ministry tightens the nation’s already stingy refugee policy. A petition to deport the Yemenis has gained more than 700,000 signatures and provoked xenophobic rallies throughout Korea. Park Won-soon, the mayor of Seoul and an old colleague of Moon’s, has called for compassion and said that the Blue House has been remiss: “We Koreans, too, were once refugees.”

Though Moon wishes to emulate FDR, he reminds me, in many ways, of President Obama. Both men are unusually bookish politicians with roots in activism and social justice law. Both bear the dreams and defeats of their fathers and entered office as symbols of social change, promising a new kind of governance. For now, Moon is well positioned to make good on his pledge—he enjoys an approval rating of 70 percent and a majority in the National Assembly. But his fate depends on what happens with the North, with respect to both denuclearization and a peace treaty to officially end the Korean War. In early July, following reports of continued North Korean arms development and an unproductive meeting between Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and North Korea’s Kim Yong-chol, the White House was reportedly chagrined. The Blue House, meanwhile, appealed for calm. Moon’s spokesman told the Korean public, “As the saying goes, ‘You can’t get full from one drink.’”

—July 19, 2018

No comments:

Post a Comment