ESSAY

THE WORLD WAR II “WONDER DRUG” THAT NEVER LEFT JAPAN

For Workers and Soldiers, Taking Methamphetamine Was a Patriotic Duty That Hooked a Generation

Students in Chiran, Japan wave to kamikaze pilots during World War II. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

by PETER ANDREAS | JANUARY 8, 2020

Amphetamines, the quintessential drug of the modern industrial age, arrived relatively late in the history of mind-altering substances—commercialized just in time for mass consumption during World War II. In fact, the introduction of what is now Japan’s most popular illegal drug began as a result of the state promoting its use during the war.

With the possible exception of opium during the Opium Wars, no drug has ever received a bigger stimulus from armed conflict. “World War II probably gave the greatest impetus to date to legal, medically-authorized as well as illicit black market abuse of these pills on a worldwide scale,” wrote Lester Grinspoon and Peter Hedblom in their classic 1975 study, The Speed Culture. Whether in the air or in the trenches, the war enabled the rapid proliferation of a synthetic stimulant that was particularly well-suited to sleepless work and intense concentration.

Amphetamines—often called “pep pills,” “go pills,” “uppers,” or “speed”—are a group of synthetic drugs that stimulate the central nervous system, reducing fatigue and appetite and increasing wakefulness and imparting a sense of well-being. Methamphetamine is a particularly potent and addictive form of the drug, best known today as “crystal meth.” All amphetamines are now banned or tightly regulated around the globe.

While produced entirely in the laboratory, amphetamines owe their existence to the search for an artificial substitute for the ma huang plant, better known in the West as ephedra. This relatively scarce desert shrub has been used as an herbal remedy in China for more than 5,000 years and is often ingested to treat common ailments such as coughs and colds and to promote concentration and alertness—including historically by night guards patrolling the Great Wall of China.

In 1887, Japanese chemist Nagayoshi Nagai successfully extracted the plant’s active ingredient, ephedrine, which closely resembled adrenaline; and in 1919, another Japanese scientist, A. Ogata, developed a synthetic substitute for ephedrine. But it was not until amphetamine was synthesized in 1927 at a UCLA laboratory by the young British chemist Gordon Alles that a formula was available for commercial medical use.

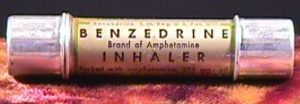

The Benzedrine inhaler hit the market in 1932 as an over-the-counter remedy for asthma and congestion. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Alles sold it to the Philadelphia pharmaceutical company Smith, Kline & French, which brought it to market as the Benzedrine inhaler in 1932 (an over-the-counter product to treat asthma and congestion), before introducing it in tablet form a few years later. “Bennies” were widely promoted as a wonder drug for all sorts of ailments, from fighting depression to obesity, with little apparent concern for or awareness of their addictive potential, and of the risks of longer-term physical and psychological damage. And thus, the stage was set for large-scale pill pushing to reach the battlefield when the next war broke out.

German, British, American, and Japanese forces ingested large amounts of amphetamines during World War II, but nowhere did the drug’s use have a more long-lasting societal impact than in Japan. The Japanese imperial government sought to give its fighting capacity a pharmacological edge, and so it contracted out methamphetamine production to domestic pharmaceutical companies for use during the war effort.

The tablets were distributed to pilots for long flights and to soldiers for combat, under the trade name Philopon (also known as Hiropin). In addition, the government gave munitions workers and those laboring in other defense-related factories methamphetamine tablets to increase their productivity.

Japanese called the war stimulants “senryoku zokyo zai” or “drug to inspire the fighting spirits.” Defense workers ingested these drugs to help boost their output. In the all-out push to increase production, strong prewar inhibitions against drug use were swept aside. It is not difficult to understand why. As researchers such as political scientist Lukasz Kamienski have documented, total war required total mobilization, from factory to battlefield. Pilots, soldiers, naval crews, and laborers were all routinely pushed beyond their natural limits to stay awake longer and work harder. In this context, taking stimulants was seen as a patriotic duty.

Kamikaze pilots took large doses of methamphetamine, via injection, before their suicide missions. They were also given pep pills stamped with the crest of the emperor. These consisted of methamphetamine mixed with green tea powder and were called Totsugeki-Jo or Tokkou-Jo, known otherwise as “storming tablets.” Most kamikaze pilots were young, often only in their late teens. Before the injection of Philopon, the pilots undertook a warrior ceremony in which they were presented with sake, wreaths of flowers, and decorated headbands.

Japanese called the war stimulants “senryoku zokyo zai” or “drug to inspire the fighting spirits.” Defense workers ingested these drugs to help boost their output. In the all-out push to increase production, strong prewar inhibitions against drug use were swept aside.

Although soldiers from many countries returned home from the war with amphetamine habits, the problem was most severe in Japan, which experienced the first drug epidemic in the history of the country. Many soldiers and factory workers who had become hooked on the speed during the war continued to consume it into the postwar years, when it was easy to get the drugs because the Imperial Army’s post-war surplus was dumped into the domestic market.

These stockpiles of the drug then brought about other dramatic changes in Japanese society. Upon surrendering in 1945, the country had massive stores of Hiropin in warehouses, military hospitals, supply depots, and caves peppered throughout its territories. Some of the supply was sent to public dispensaries for distribution as medicine, but the rest was diverted to the black market rather than destroyed. There, the country’s Yakuza crime syndicate took over much of the distribution, and the drug trade would eventually become its most important source of revenue.

Pervitin, a methamphetamine brand that German soldiers used during WWII, dispensed the tablets in these containers. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Any tablets not diverted to illicit markets remained in the hands of pharmaceutical companies. In the wake of the traumas and dislocations of the war, a depressed and humiliated population offered an easy target. As Kamienski noted, “The pharmaceutical industry advertised stimulants as a perfect means of boosting the war-weary population and restoring confidence after a painful and debilitating defeat.” The drug companies mounted advertising campaigns to encourage consumers to purchase over-the-counter medicine sold as “wake-a-mine.” The product was pitched as offering “enhanced vitality.” In No Speed Limit: The Highs and Lows of Meth, journalist Frank Owen reports that these companies also sold “hundreds of thousands of pounds” of “military-made liquid meth” left over from the war to consumers, who did not need a prescription to purchase the drug.

With an estimated 5 percent of Japanese people between the ages of 18 and 25 taking the drug, many became intravenous addicts in the early 1950s.

Another driver of the epidemic was the existence of large, new U.S. military bases on the islands, which had never previously been occupied by a foreign power. National newspaper Asahi Shinbun wrote that U.S. servicemen were responsible for spreading amphetamine usage from large cities to small towns. Indeed, the Japanese government’s Narcotics Section arrested 623 American soldiers for drug trafficking in 1953. However, according to historian Miriam Kingsberg, most drug scandals involving U.S. soldiers garnered little coverage by the major papers out of “deference” to “American-Japanese friendship.”

Surging methamphetamine use led to increasingly strict state regulation of the drug: The 1951 Stimulant Control Law banned methamphetamine possession, and penalties were increased three years later. But these increases did not stop the rise in arrests for amphetamine abuse, which jumped from 17,500 people in 1951 to 55,600 in 1954. During the early 1950s, arrests in Japan for stimulant offences made up more than 90 percent of total drug arrests.

In an anonymous survey by the Ministry of Welfare in 1954, 7.5 percent of respondents reported having sampled Hiropon. Meanwhile the Asahi Shinbun published an estimate that 1.5 million Japanese were methamphetamine users in 1954, out of a total population of some 88 million.

The high rates of amphetamine use in Japan started to subside by the late 1950s and early 1960s, once economic growth began to create more jobs. Nevertheless, methamphetamine would remain the most popular illicit drug in Japan for decades to come.

PETER ANDREASis the John Hay Professor of International Studies at Brown University, where he holds a joint appointment between the Department of Political Science and the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs. His new book, Killer High: A History of War in Six Drugs, explores the relationship between warfare and mind-altering substances, from ancient times to the present.

BUY THE BOOK Skylight Books | Powell’s Books | Amazon

Killer High

A History of War in Six Drugs

Peter Andreas

Description

Reviews and Awards

"Killer High, well-written and extensively researched, shows how the drugs-war relationship has served state interests and ambitions." -- Katharine Neill-Harris, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice Books

"Since time immemorial, soldiers have consumed mind-altering substances; Andreas (International Studies/Brown Univ.; Smuggler Nation: How Illicit Trade Made America, 2013, etc.) delivers an impressive, often unsettling history of six." --Kirkus

"Peter Andreas...has drawn from an impressive and eclectic mix of sources to give psychoactive and addictive drugs a fuller place in discussions of war. His book steps back from the headlines to draw a full arc that reads as both complement and counterpoint to enduring fables and simplistic accounts surrounding wars and nations you may think you know. Organized into six main chapters on the varied drugs-war relationships - one each for alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, opium, speed and cocaine - it offers a fascinating interpretive lens for drugs' roles in making war and, in turn, wars' roles in spreading drugs around the world." --C.J. Chivers, New York Times

"Peter Andreas always writes about captivating topics, but his take on the combination of violence and drugs may be his best yet. This is a history of conflict and capitalism and how the two are intertwined. It also provides a fascinating perspective on consumer behavior and the creation of our drugged culture. Beautifully written, this book is both scholarly and wonderfully entertaining. A great read!" --Miguel A. Centeno, Vice Dean and Musgrave Professor of Sociology, Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University

"Ingeniously plotted, briskly written, and strikingly illustrated, Killer High delivers a kaleidoscopic trip through the history of drugs and war. Peter Andreas looks at the drug-war relationship from every angle: how combatants and noncombatants used drugs; how wars were fought through, for, or against drugs; and how wars shaped the fates of drugs, often speeding their rise as global commodities." --David Courtwright, author of Forces of Habit and The Age of Addiction

"Killer High frees history from the names-and-dates straightjacket and looks more deeply at why we fight. From the drinking binges of Alexander the Great to anti-drug campaigns in Afghanistan and Latin America, it illuminates the hidden relationship between drugs and war. By reimagining the past so insightfully, it helps us understand the conflicts of today and tomorrow." --Stephen Kinzer, Senior Fellow in International and Public Affairs, Watson Institute, Brown University, and former foreign correspondent, New York Times

" "Peter Andreas is that rare political scientist who can weave serious and compelling historical arguments and who writes with the breadth and clarity of a public intellectual. Killer High is a killer book-the definitive work on the history of drugs and warfare." --Paul Gootenberg, Stony Brook University, author of Andean Cocaine: The Making of a Global Drug

"Killer High is a captivating book, laced with provocative insights about the enduring relationship between drugs and war and further enlivened with entertaining flashes of wit." --Andrew Bacevich, author of The Age of Illusions: How Americans Squandered Their Cold War Victory

===

Top reviews from the United States

Huff Daddy

4.0 out of 5 stars Speed School

Reviewed in the United States on September 8, 2007

Verified Purchase

I found this book so fascinating I could barely put it down. It is very easy to read and basically tells you everything you could ever want to know about the history and use of meth.

I give it four stars for two reasons. One, I found the outline of the book somewhat chaotic. The book is not laid out chronologically or otherwise but more like a series of individual stand alone essays. I had a feeling of a lack of continuity but it really doesn't take away from the book. I guess I would just be more comfortable with a standard chronological history.

Two, there is an extensive bibliography but I would have preferred end notes or foot notes. I have no reason to doubt the quality of the author's research, but I do like to follow up on claims and statistics myself and it is a little more difficult when all the references are just listed in a bibliography.

The book broke down many presumptions that I had about meth. I was utterly amazed at how old the drug is and that meth abuse is nothing new. The impact of politics and media I guess. Never did I feel the author glamorized the drug.

This should be a must read before you make any intelligent comments regarding meth in conversation.

Read less

10 people found this helpful

Helpful

Report abuse

Ralph A. Weisheit

5.0 out of 5 stars A very good overview.

Reviewed in the United States on October 28, 2007

Verified Purchase

As an academic I've been intensely studying the issue of methamphetamine for several years now and am impressed by the range of methamphetamine-related issues covered by the author -- everything from a bit of history, to its spread through the West, to cooking the drug, to treatment, and to the effects of policies designed to control it. As a journalist Owen has the skill to draw the reader in, unlike many academic writers. Now and then he states things with certainty that an academic would waffle on, but overall the book is on the mark. And, as a journalistic account there are brief periods of "over the top" comments, but they are mild compared with the comments often made by the authorities. For example, he correctly dismisses the idea that meth is instantly addictive and is an addiction from which recovery is rare. He also takes issue with using the word epidemic to describe the current problem -- though I would argue that a correct description would be that the drug has created a series of localized epidemics rather than a national one. This book is an excellent introduction to the issue. I wish the author had included more sources, but that's just the academic in me talking.

2 people found this helpful

Helpful

Report abuse

Nancy Lombardo

3.0 out of 5 stars No Speed Limit By Frank Owen

Reviewed in the United States on April 20, 2010

Verified Purchase

This book was very well written, but it gave way to many facts for anyone's brain to process. When I first read this book I thought that it was promoting the usage of crystal meth because it was explaining how good the feeling was while on the drug. But remember the book explains the highs and the lows of crystal meth. It goes through a series of different stories that explains peoples experiences while on the drug. It also tells you about ways these people tried to quit using the drug which is what caught my attention the most. People tried all types of things such as church and rehab ( the book explains that rehab was not a good source for trying to quit because it reminds you of the drug all the time). This book also explains how meth really came into production and where the drugs are being imported and exported to for example California, Mexico and Missouri were mentioned the most in this book. Groups such as the Hells Angels and drug lords in Mexico and Columbia formed deals with each other to keep the drug circulating around Mexico. This book also explains the hardship that children go through while their parents are cooking meth in their own homes. While reading this you will really feel bad for the children that have to be put in situations like this. Children had gotten taken away from their parents and at some points their parents didnt care as long as they had the drug with them at all time. Children have died and been contaminated due to constantly being around the drug.

I recommend this book for teenagers older than the age of seventeen and adults. This book has a small amount of bad bad language but it does have a lot of sexual references. Do not read this book if you plan on taking crystal meth because I can see people wanting to try it after reading the book. Toward the end of the book you will be relieved that its over because it goes into a lot of debt about meth. Overall its a good book.

Read less

Helpful

Report abuse

sdw

5.0 out of 5 stars Exactly as expected.

Reviewed in the United States on November 22, 2019

Verified Purchase

Have skimmed book but haven't read it completely. Very happily looking forward to the time I can spend reading entire book. Arrived sooner than expected. Yippee!

Helpful

Report abuse

Michael Lacoe

4.0 out of 5 stars Intersting Historical Insights into Crystal Meth as a Commodity

Reviewed in the United States on October 1, 2007

Verified Purchase

Mr. Owen has written an interesting, at times thought-provoking, historical account of the rise and rise of Crystal Meth, both as a market-traded commodity and the government's precarious hold on it's distribution and control. For those seeking a deeper understanding of this powerful illicit substance from the point-of-view of addiction and treatment, a self-help book this is not. For those looking for a thoughtful personal memoir on the ravages of addiction to crystal meth, one should look elsewhere. Personally, I don't think that book has definitively yet to be written. But as an always thoughtful and well-researched piece of journalism I think Mr. Owen has succeeded admirably. I learned much about the evolution of this drug going back to it's origins in the 19th century. The data is indeed fascinating, at times riveting. And Mr. Owen earned my trust as a man who does not flaunt any particular agendas or hard-core dogmas. That alone makes it a rarity as a valid piece of writing in what is admittedly a fledgling subject matter for current circumspection.

3 people found this helpful

Helpful

Report abuse

===

Killer High: A History of War in Six Drugs Kindle Edition

by Peter Andreas (Author) Format: Kindle Edition

4.7 out of 5 stars 51 ratings

See all formats and editions

Kindle$15.83

====

Write a review

Kusaimamekirai

Mar 22, 2021Kusaimamekirai rated it it was amazing

Alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, opium, cocaine, and amphetamines.

While most of us aware of the short and long term harm these substances can cause, how often do we consider them in the context of wars? How many wars occur because of them? For them? Against them? On them?

Peter Andreas in “Killer High” reminds us that the answer is, in some form or another, more often than not.

Governments have been both overthrown because of them as well as financed from them.

Some wars, and their successes, would have been impossible without them (see WW2 and the shocking amount of government subsidized methamphetamines. Both with the Axis and the Allied powers).

Some drugs, like cocaine and the war on drugs in general, provided a convenient excuse to continue funding weapons and a military bureaucracy for a United States desperately looking to justify military spending with the end of the Cold War. Or as an army general once said about a U.S. military present in Panama:

“Reflecting the new priorities, the US Southern Command in Panama was transformed into a de facto forward base for cocaine interdiction. Its commander, General Maxwell Thurman, frankly observed that the drug war was ‘the only war we’ve got.’"

This is such a fascinating book that is filled with lots of interesting information that even those familiar with these substances will learn something new here. Did you know for example that:

“The thirsty Vikings even managed to brew beer on board their longships during raiding campaigns. The skulls of their dead victims were turned into drinking containers. The Nordic toast ‘skal’ comes from the word scole, which means skull.”

“Warren Delano II, the grandfather of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the creator of the family fortune, profited from shipping opium to China, calling it a ‘fair, honorable and legitimate trade’ that was no worse than trading in alcohol.”

“The name “heroin,” the trademark for which was registered by Friedrich Bayer & Co., derived from the German heroisch, which meant ‘heroic.’”

If there is one criticism I guess it would be that there isn’t much original research here. The vast majority of the section on methamphetamine use in the Third Reich comes from one book (Norman Ohler’s ‘Blitzed’, which is incidentally well worth the read), and the author often refers back to his own work in multiple citations (not a fan of this practice. “This is true because….I said it is”)

But if this is new material for you, as it mostly was for me, than it is not much of an issue.

Highly recommended for anyone who wants to better understand the myriad and intertwined connections between illicit drugs and war.

flag5 likes · Like · 2 comments · see review

====

Paul

Oct 04, 2020Paul rated it really liked it

Dry and competent. The way I like my non-fiction.

flag2 likes · Like · comment · see review

Hannah Peacock

Aug 04, 2021Hannah Peacock rated it really liked it

An interesting survey of the relationship between war and drugs. I thought the final 2 sections (cocaine and conclusion) were particularly interesting, partly because many of the drug war events have happened in my lifetime and partly because the author discusses the nuance at how we could curb drug-related violence, largely caused by militarization of anti-drug groups and police.

While not in-depth at some points, this novel provides a good starting point for those curious about a history of the relationship between war and drugs. (less)

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Angelica

Apr 15, 2021Angelica rated it really liked it

An incredibly important read to provide context on our history as it pertains to the war on drugs.

flag1 like · Like · comment · see review

Scott Martin

Mar 27, 2020Scott Martin rated it liked it

(3.5 stars). This work looked at human history, especially war and law enforcement, through the prism of a series of drugs/substances. Discussing the impact of alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, opium/heroin, cocaine and amphetamines, the author notes the history, the first uses by people, and how each was used in and/or drove conflict. Depending on the drug/substance in question, different parts of the world at different times in history reacted differently. However, all of the substances still have military impacts/applications today, for better or worse.

It is a very readable work, but given the scope, it tends to be a surface-level analysis of various nations/conflicts and the role of a specific substance. Worth a least a read and a good start for discussions and impacts. You can agree or disagree, but it should spark some discussion/debate. (less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Alex Anderson

Aug 20, 2020Alex Anderson rated it liked it

An average rating, nothing more.

An entertaining survey of the topic.

Not much to add to the superficial knowledge any well-read history buff doesn't already possess.

The last chspter in the book, a speculative one, is one of the most interesting chapters in the book.and has the sunstance to expand into a book itself.

But worth a read for some unfamiliar details.

Leaves the reader craving something more substantial, written by an author with a little more depth & talent. (less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Dutchermann

Jan 03, 2021Dutchermann rated it really liked it

This book will integrate nicely into my History & Globalization of the Drug Trade class. The chapter on amphetamines would be an interesting read for a general world history class when studying WWII.

flagLike · comment · see review

Susan

May 22, 2020Susan rated it really liked it

See my review at Reading World (less)

flagLike · comment · see review

Jloftin

Jan 02, 2021Jloftin rated it really liked it

This book was interesting and introduced a new side to several wars that I have never considered.

It was a bit speculative, but ultimately entertaining.

flagLike · comment · see review

Charlie

Aug 01, 2020Charlie rated it really liked it

The book is a survey of the interaction between drugs and war throughout history, focusing on alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, opium, amphetamines and cocaine. Some sections are more “readable” than others, that is, more narrative than encyclopedic. Lots of fun facts and a good overview for a general audience or people interested in this specific topic. Lots of focus on World War II, the Opium Wars and the war on drugs in Mexico. Overall I enjoyed this title!

No comments:

Post a Comment